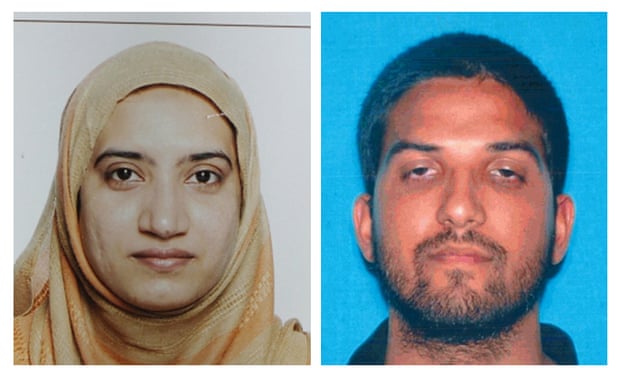

The San Bernardino County government on Friday night said the FBI told its staff to tamper with the Apple account of Syed Farook, who with his wife, Tashfeen Malik, carried out the December shooting in which 14 people were killed.

The development matters because the change made to the account – a reset of Farook’s iCloud password – made it impossible to see if there was another way to get access to data on the shooter’s iPhone without taking Apple to court.

“The county was working cooperatively with the FBI when it reset the iCloud password at the FBI’s request,” read a post on San Bernardino County’s official Twitter account.

Late on 20 February the FBI said that it “worked with” county officials to reset the iCloud password, as discovery of the locked phone was “a logical next step was to obtain access to iCloud backups for the phone in order to obtain evidence related to the investigation in the days following the attack,” according to the statement from an FBI spokesman.

On 16 February, a federal judge ordered Apple to write and digitally sign software that would make it easier for the US government to guess the 4-digit passcode on Farook’s device – not to be confused with the iCloud password.

Apple contends such a move would violate user trust, the security of its products and a core tenet of its business. The FBI counters that Apple has placed marketing over national security.

But Apple executives say there is a way this legal battle, which will shape digital privacy for years to come, could have been avoided – at least for now.

The FBI seeks data on Farook’s iPhone, which was owned by the San Bernardino County government – his employer. But such data can be backed up into Apple’s cloud service automatically if the phone connects to one of its default Wi-Fi networks. People often pick places such as their homes or offices.

Apple, which has the technical ability to get inside an iCloud account but not always an individual phone, has already provided the FBI with any iCloud data it has for Farook. Those backups only go back to 19 October, six weeks before the shooting.

That feature is disabled as a security precaution if someone changes the iCloud password for an account.

The FBI listed four options it said it had discussed with Apple after the shooting. Among those was a suggestion “to attempt an auto-backup of the subject device with the related iCloud account”.

This would not work, the government’s counsel said, “because neither the owner nor the government knew the password to the iCloud account, and the owner, in an attempt to gain access to some information in the hours after the attack, was able to reset the password remotely, but that had the effect of eliminating the possibility of an auto-backup”.

The resulting changes made the data “permanently inaccessible”, the lawyers wrote, saying that “Apple has the exclusive technical means” that would allow the search of Farook’s iPhone to take place.

The government has said it wants to know if Farook communicated with any of the people he killed on 2 December or if, during the time his phone did not back up to iCloud, he communicated with any unknown co-conspirators. Farook had another phone he destroyed.

The hours after the shooting in San Bernardino were no doubt chaotic, as victims began to sort through the tragedy. It would make sense, for instance, if a county employee tried to get into the shooter’s Apple account, in the search for clues.

But the county took the unusual step Friday night of stating that the only reason it tampered with potential evidence was because the FBI told it do so.

Under Apple’s current security settings, the company can no longer help authorities unlock physical iPhones. The passcodes, used to get through the lock screen, are encrypted within the device. Apple does not keep them in some master database.

But it is easier to get into an iCloud storage account, which can be accessed from any machine. There are two ways to get into someone’s account: know his password or be able to guess his security questions, such as: “Where did you go to high school?”

It is possible that Farook’s employer, the county, could have had enough knowledge to assist in either method. It remains unclear if this plan would have worked had the iCloud account not been tampered with.

It is possible Farook could have turned automatic updates off. Since Apple has enhanced its security practices, it has been well-covered that if iCloud backups are deactivated, it can be very difficult to recover data from an iPhone.

Apple has acknowledged that it does have decryption keys to access to the iCloud account, but the FBI says this is legally irrelevant to the access it seeks now.

“The reset of the iCloud account password does not impact Apple’s ability to assist with the the court order under the All Writs Act,” the bureau said.

Additionally, the agency suggested that what remains inaccessible on the phone might never have made it to the remote iCloud servers, which the phone stopped backing up in October, months before the shooting.

“Even if the password had not been changed and Apple could have turned on the auto-backup and loaded it to the cloud, there might be information on the phone that would not be accessible without Apple’s assistance as required by the All Writs Act order, since the iCloud backup does not contain everything on an iPhone,” the bureau said.

Apple’s end-to-end encrypted iMessage chats optionally back up to associated iCloud accounts, as do photos and videos on the native Apple clients. Applications, to include secure communications applications, often do not.

In a conference call with reporters on Friday, however, an Apple executive noted that had the password reset not happened, America’s most valuable company might not be going to court with its own government.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Danny Yadron , Spencer Ackerman and Sam Thielman

The development matters because the change made to the account – a reset of Farook’s iCloud password – made it impossible to see if there was another way to get access to data on the shooter’s iPhone without taking Apple to court.

“The county was working cooperatively with the FBI when it reset the iCloud password at the FBI’s request,” read a post on San Bernardino County’s official Twitter account.

Late on 20 February the FBI said that it “worked with” county officials to reset the iCloud password, as discovery of the locked phone was “a logical next step was to obtain access to iCloud backups for the phone in order to obtain evidence related to the investigation in the days following the attack,” according to the statement from an FBI spokesman.

On 16 February, a federal judge ordered Apple to write and digitally sign software that would make it easier for the US government to guess the 4-digit passcode on Farook’s device – not to be confused with the iCloud password.

Apple contends such a move would violate user trust, the security of its products and a core tenet of its business. The FBI counters that Apple has placed marketing over national security.

But Apple executives say there is a way this legal battle, which will shape digital privacy for years to come, could have been avoided – at least for now.

The FBI seeks data on Farook’s iPhone, which was owned by the San Bernardino County government – his employer. But such data can be backed up into Apple’s cloud service automatically if the phone connects to one of its default Wi-Fi networks. People often pick places such as their homes or offices.

Apple, which has the technical ability to get inside an iCloud account but not always an individual phone, has already provided the FBI with any iCloud data it has for Farook. Those backups only go back to 19 October, six weeks before the shooting.

That feature is disabled as a security precaution if someone changes the iCloud password for an account.

The FBI listed four options it said it had discussed with Apple after the shooting. Among those was a suggestion “to attempt an auto-backup of the subject device with the related iCloud account”.

This would not work, the government’s counsel said, “because neither the owner nor the government knew the password to the iCloud account, and the owner, in an attempt to gain access to some information in the hours after the attack, was able to reset the password remotely, but that had the effect of eliminating the possibility of an auto-backup”.

The resulting changes made the data “permanently inaccessible”, the lawyers wrote, saying that “Apple has the exclusive technical means” that would allow the search of Farook’s iPhone to take place.

The government has said it wants to know if Farook communicated with any of the people he killed on 2 December or if, during the time his phone did not back up to iCloud, he communicated with any unknown co-conspirators. Farook had another phone he destroyed.

The hours after the shooting in San Bernardino were no doubt chaotic, as victims began to sort through the tragedy. It would make sense, for instance, if a county employee tried to get into the shooter’s Apple account, in the search for clues.

But the county took the unusual step Friday night of stating that the only reason it tampered with potential evidence was because the FBI told it do so.

Under Apple’s current security settings, the company can no longer help authorities unlock physical iPhones. The passcodes, used to get through the lock screen, are encrypted within the device. Apple does not keep them in some master database.

But it is easier to get into an iCloud storage account, which can be accessed from any machine. There are two ways to get into someone’s account: know his password or be able to guess his security questions, such as: “Where did you go to high school?”

It is possible that Farook’s employer, the county, could have had enough knowledge to assist in either method. It remains unclear if this plan would have worked had the iCloud account not been tampered with.

It is possible Farook could have turned automatic updates off. Since Apple has enhanced its security practices, it has been well-covered that if iCloud backups are deactivated, it can be very difficult to recover data from an iPhone.

Apple has acknowledged that it does have decryption keys to access to the iCloud account, but the FBI says this is legally irrelevant to the access it seeks now.

“The reset of the iCloud account password does not impact Apple’s ability to assist with the the court order under the All Writs Act,” the bureau said.

Additionally, the agency suggested that what remains inaccessible on the phone might never have made it to the remote iCloud servers, which the phone stopped backing up in October, months before the shooting.

“Even if the password had not been changed and Apple could have turned on the auto-backup and loaded it to the cloud, there might be information on the phone that would not be accessible without Apple’s assistance as required by the All Writs Act order, since the iCloud backup does not contain everything on an iPhone,” the bureau said.

Apple’s end-to-end encrypted iMessage chats optionally back up to associated iCloud accounts, as do photos and videos on the native Apple clients. Applications, to include secure communications applications, often do not.

In a conference call with reporters on Friday, however, an Apple executive noted that had the password reset not happened, America’s most valuable company might not be going to court with its own government.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Danny Yadron , Spencer Ackerman and Sam Thielman

No comments:

Post a Comment