After the impeachment vote against Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff, attention is shifting to her accuser-in-chief, who is charged with greater crimes – but looks more likely to escape justice.

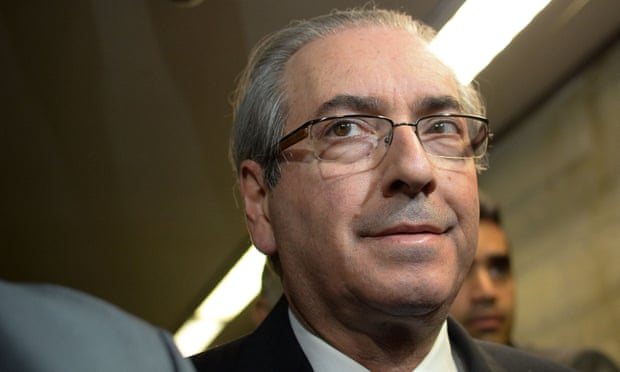

The lower house speaker, Eduardo Cunha, an evangelical conservative and conspiratorial mastermind, started and steered the drive to remove the country’s first female leader from power as a means of reducing the risks to himself from investigations by a congressional ethics committee and prosecutors for alleged perjury, money laundering and receipt of at least $5m in bribes.

After being condemned on Sunday for fiscal irregularities that had gone unpunished when used by the previous administration, Rousseff turned her fiercest fire on Cunha.

“This process was initiated by a misuse of power, revenge, an explicit revenge,” she told a press conference of foreign journalists on Tuesday. “I feel the victim of a process, a process in which my judges, especially the speaker of the chamber, has a background that does not behove him to be a judge of anything – it behoves him as a defendant.”

The public appears to agree. Brazil loathes its politicians, but none more so than Cunha. A Datafolha survey this month found 77% of the public wanted him to be stripped of his mandate, compared with 61-67% for Dilma, who is blamed for a dire recession, political turmoil and failing to stop corruption even though she is not accused of any crime.

But the political tide appears to be moving in Cunha’s favour. Almost as soon as the vote was over, conservative allies – many of whom are likely to join a new government next month – began lobbying for him to be protected. The deputy speaker, Waldir Maranhão, called for the ethics committee investigation into Cunha to be limited.

Many observers say he is now far more likely to remain free and in office by the end of the year than Rousseff or the previous Workers party president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The situation looked very different in early December, when Cunha appeared to be on the ropes. Investigators in the vast Lavo Jato (Car Wash) corruption inquiry had accused him of taking bribes of at least $5m in relation to Petrobras contracts and laundering money through his church. Swiss authorities revealed he had secret accounts, which he had denied.

His last hope, it seemed, was to secure a deal with the ruling Workers party to prevent the lower house ethics council stripping him of his mandate and his parliamentary protection from prosecution. But Rousseff’s aides refused to play ball.

Immediately, Cunha gave the green light to an impeachment request. It was both retaliation and a bid for survival by a master tactician.

Allies and enemies alike speak in awed terms of the 57-year-old’s knowledge of congressional procedure and his bloody-mindedness in punishing those who cross him. Some compare his machiavellian streak to the Mr Burns character in The Simpsons, to whom he bears some resemblance. More common is a comparison with Frank Underwood in House of Cards, not least because Cunha’s files on his fellow deputies’ secrets are legendary.

Trained as an economist, Cunha started his political life as a protege of Fernando Collor, the only previous president to have been impeached since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. A convert to the Assembly of God – one of the country’s biggest evangelical churches – he rose to notoriety as the outspoken host of a radio show on an evangelical station. With support from the Christian right, he won his first seat in the chamber of deputies in 2003.

He is now one of three senior figures in the Brazilian Democratic Movement party (PMDB), which has no ideology beyond securing power and brokering influence. Until last month, it was allied with Rousseff’s Workers party and as deeply implicated in the vast corruption scandal exposed by Lava Jato prosecutors.

Unlike Rousseff, all three of the PMDB’s most powerful politicians have been named in plea bargains related to the investigation. Vice-President Michel Temer – who is preparing to take power if the senate forces Rousseff to step aside next month – has been accused of appointing lobbyists to pay bribes and manipulating appointments at Petrobras so that his allies controlled the flow of campaign donations. Renan Calheiros, the head of the senate, is being investigated by the supreme court for seven alleged crimes relating to the $17bn Petrobras scandal, including bribery and obstruction of justice. Both deny any wrongdoing.

As does Cunha, who is next in line to the presidency. But he has become the greatest focus of public anger – not least due to the profligate lifestyle revealed by the investigation into bribery allegations.

On a nine-day family holiday in Miami at the end of 2013, the speaker and his family are said to have spent more than $40,000. This included his wife Claudia Cruz’s shopping splurges on designer goods – $1,595 on Giorgio Armani, $3,803 on Salvatore Ferragamo and $3,531 on Ermenegildo Zegna – and restaurant bills that often ran to more than $1,000. In the two months that followed, there were similar blowouts in Paris, New York and Zurich. Prosecutors claimed this was completely incompatible with his declared annual income of about $120,000. They also allege that Cunha and his wife owned a fleet of eight luxury cars, including a Porsche, all of which were registered under the name of Jesus.com and C3 Productions.

But the chances of a conviction are slim. Last month, Brazil’s supreme court – the only judicial body that can prosecute sitting politicians – agreed to accept the charges against Cunha, but it has yet to set a date for a trial. Precedent suggests it may never do so, though there have been exceptions in recent months.

The ethics council has the authority to strip away the immunity of office, but it appears to have run into a quagmire. Contrary to the quickfire process of Rousseff’s impeachment, Cunha has dragged out the process of the ethics council investigation for a record of more than 170 days.

“This started in October of last year and now we are in April, but nothing has happened,” said Osmar Serraglio, a deputy from Paraná from the same PMDB party as Cunha. “It’s shameful for the house.”

During this time the composition of the members has changed in his favour. In early April, out went one of his chief critics, Fausto Pinato – who told police he was threatened last November – and in came an evangelical ally, Tia Eron. Now the speaker is believed to have a majority in the council

. Allies in the conservative evangelical bloc are calling for an amnesty.

Serraglio rejects the word amnesty – which has no legal basis in the Brazilian constitution – but he said Cunha was unlikely to be punished for lying because the perjury occurred during a previous mandate and legal precedent suggests people are not obliged to incriminate themselves even if it means lying under oath. As a result, he said deputies had to find a solution.

“Nobody is saying there aren’t corruption problems,” he said. “But for the lower house of congress not to be humiliated, we need to find a way out.”

Any suggestion that Temer might help Cunha evade punishment infuriates their critics.

“If this news is confirmed, it would highlight the absurdity of this entire process,” said Jean Wyllys, a PSOL deputy, who called Cunha a “gangster” during the impeachment vote. “It would be a tenebrous deal between two politicians who are rejected by the overwhelming majority of the population. One, who is accused of corruption, money laundering and other crimes, would have arranged for the other to become a president without a free direct election, and in return he would get an amnesty.”

Analysts expect the domestic media – which is predominantly supportive of the centre-right – to gradually dial down their coverage of corruption.

“I think he will get away with it,” said Ana Claudia Farranha, a law professor at the University of Brasília. “After impeachment, attention will shift to Temer, and Cunha’s actions and corruption will disappear from the headlines. He will be forgotten.”

Lava Jato prosecutors have vowed to continue their investigation with the same intensity regardless of the government, but their powers could be muted by a new justice minister. And even if they find more evidence of wrongdoing, Cunha and other politicians will remain at liberty as long as the supreme court and the ethics committee leave cases pending.

That could yet change, but for the moment, it looks as if the millions who took to the streets to unseat Rousseff in the name of anti-corruption may soon find themselves wondering whether they helped a politician who was even more despised off the hook.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Jonathan Watts

The lower house speaker, Eduardo Cunha, an evangelical conservative and conspiratorial mastermind, started and steered the drive to remove the country’s first female leader from power as a means of reducing the risks to himself from investigations by a congressional ethics committee and prosecutors for alleged perjury, money laundering and receipt of at least $5m in bribes.

After being condemned on Sunday for fiscal irregularities that had gone unpunished when used by the previous administration, Rousseff turned her fiercest fire on Cunha.

“This process was initiated by a misuse of power, revenge, an explicit revenge,” she told a press conference of foreign journalists on Tuesday. “I feel the victim of a process, a process in which my judges, especially the speaker of the chamber, has a background that does not behove him to be a judge of anything – it behoves him as a defendant.”

The public appears to agree. Brazil loathes its politicians, but none more so than Cunha. A Datafolha survey this month found 77% of the public wanted him to be stripped of his mandate, compared with 61-67% for Dilma, who is blamed for a dire recession, political turmoil and failing to stop corruption even though she is not accused of any crime.

But the political tide appears to be moving in Cunha’s favour. Almost as soon as the vote was over, conservative allies – many of whom are likely to join a new government next month – began lobbying for him to be protected. The deputy speaker, Waldir Maranhão, called for the ethics committee investigation into Cunha to be limited.

Many observers say he is now far more likely to remain free and in office by the end of the year than Rousseff or the previous Workers party president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The situation looked very different in early December, when Cunha appeared to be on the ropes. Investigators in the vast Lavo Jato (Car Wash) corruption inquiry had accused him of taking bribes of at least $5m in relation to Petrobras contracts and laundering money through his church. Swiss authorities revealed he had secret accounts, which he had denied.

His last hope, it seemed, was to secure a deal with the ruling Workers party to prevent the lower house ethics council stripping him of his mandate and his parliamentary protection from prosecution. But Rousseff’s aides refused to play ball.

Immediately, Cunha gave the green light to an impeachment request. It was both retaliation and a bid for survival by a master tactician.

Allies and enemies alike speak in awed terms of the 57-year-old’s knowledge of congressional procedure and his bloody-mindedness in punishing those who cross him. Some compare his machiavellian streak to the Mr Burns character in The Simpsons, to whom he bears some resemblance. More common is a comparison with Frank Underwood in House of Cards, not least because Cunha’s files on his fellow deputies’ secrets are legendary.

Trained as an economist, Cunha started his political life as a protege of Fernando Collor, the only previous president to have been impeached since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. A convert to the Assembly of God – one of the country’s biggest evangelical churches – he rose to notoriety as the outspoken host of a radio show on an evangelical station. With support from the Christian right, he won his first seat in the chamber of deputies in 2003.

He is now one of three senior figures in the Brazilian Democratic Movement party (PMDB), which has no ideology beyond securing power and brokering influence. Until last month, it was allied with Rousseff’s Workers party and as deeply implicated in the vast corruption scandal exposed by Lava Jato prosecutors.

Unlike Rousseff, all three of the PMDB’s most powerful politicians have been named in plea bargains related to the investigation. Vice-President Michel Temer – who is preparing to take power if the senate forces Rousseff to step aside next month – has been accused of appointing lobbyists to pay bribes and manipulating appointments at Petrobras so that his allies controlled the flow of campaign donations. Renan Calheiros, the head of the senate, is being investigated by the supreme court for seven alleged crimes relating to the $17bn Petrobras scandal, including bribery and obstruction of justice. Both deny any wrongdoing.

As does Cunha, who is next in line to the presidency. But he has become the greatest focus of public anger – not least due to the profligate lifestyle revealed by the investigation into bribery allegations.

On a nine-day family holiday in Miami at the end of 2013, the speaker and his family are said to have spent more than $40,000. This included his wife Claudia Cruz’s shopping splurges on designer goods – $1,595 on Giorgio Armani, $3,803 on Salvatore Ferragamo and $3,531 on Ermenegildo Zegna – and restaurant bills that often ran to more than $1,000. In the two months that followed, there were similar blowouts in Paris, New York and Zurich. Prosecutors claimed this was completely incompatible with his declared annual income of about $120,000. They also allege that Cunha and his wife owned a fleet of eight luxury cars, including a Porsche, all of which were registered under the name of Jesus.com and C3 Productions.

But the chances of a conviction are slim. Last month, Brazil’s supreme court – the only judicial body that can prosecute sitting politicians – agreed to accept the charges against Cunha, but it has yet to set a date for a trial. Precedent suggests it may never do so, though there have been exceptions in recent months.

The ethics council has the authority to strip away the immunity of office, but it appears to have run into a quagmire. Contrary to the quickfire process of Rousseff’s impeachment, Cunha has dragged out the process of the ethics council investigation for a record of more than 170 days.

“This started in October of last year and now we are in April, but nothing has happened,” said Osmar Serraglio, a deputy from Paraná from the same PMDB party as Cunha. “It’s shameful for the house.”

During this time the composition of the members has changed in his favour. In early April, out went one of his chief critics, Fausto Pinato – who told police he was threatened last November – and in came an evangelical ally, Tia Eron. Now the speaker is believed to have a majority in the council

. Allies in the conservative evangelical bloc are calling for an amnesty.

Serraglio rejects the word amnesty – which has no legal basis in the Brazilian constitution – but he said Cunha was unlikely to be punished for lying because the perjury occurred during a previous mandate and legal precedent suggests people are not obliged to incriminate themselves even if it means lying under oath. As a result, he said deputies had to find a solution.

“Nobody is saying there aren’t corruption problems,” he said. “But for the lower house of congress not to be humiliated, we need to find a way out.”

Any suggestion that Temer might help Cunha evade punishment infuriates their critics.

“If this news is confirmed, it would highlight the absurdity of this entire process,” said Jean Wyllys, a PSOL deputy, who called Cunha a “gangster” during the impeachment vote. “It would be a tenebrous deal between two politicians who are rejected by the overwhelming majority of the population. One, who is accused of corruption, money laundering and other crimes, would have arranged for the other to become a president without a free direct election, and in return he would get an amnesty.”

Analysts expect the domestic media – which is predominantly supportive of the centre-right – to gradually dial down their coverage of corruption.

“I think he will get away with it,” said Ana Claudia Farranha, a law professor at the University of Brasília. “After impeachment, attention will shift to Temer, and Cunha’s actions and corruption will disappear from the headlines. He will be forgotten.”

Lava Jato prosecutors have vowed to continue their investigation with the same intensity regardless of the government, but their powers could be muted by a new justice minister. And even if they find more evidence of wrongdoing, Cunha and other politicians will remain at liberty as long as the supreme court and the ethics committee leave cases pending.

That could yet change, but for the moment, it looks as if the millions who took to the streets to unseat Rousseff in the name of anti-corruption may soon find themselves wondering whether they helped a politician who was even more despised off the hook.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Jonathan Watts

No comments:

Post a Comment