Regular beatings, sleep deprivation, stress positions and solitary confinement are among the tools used by China’s anti-corruption watchdog to force confessions, according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

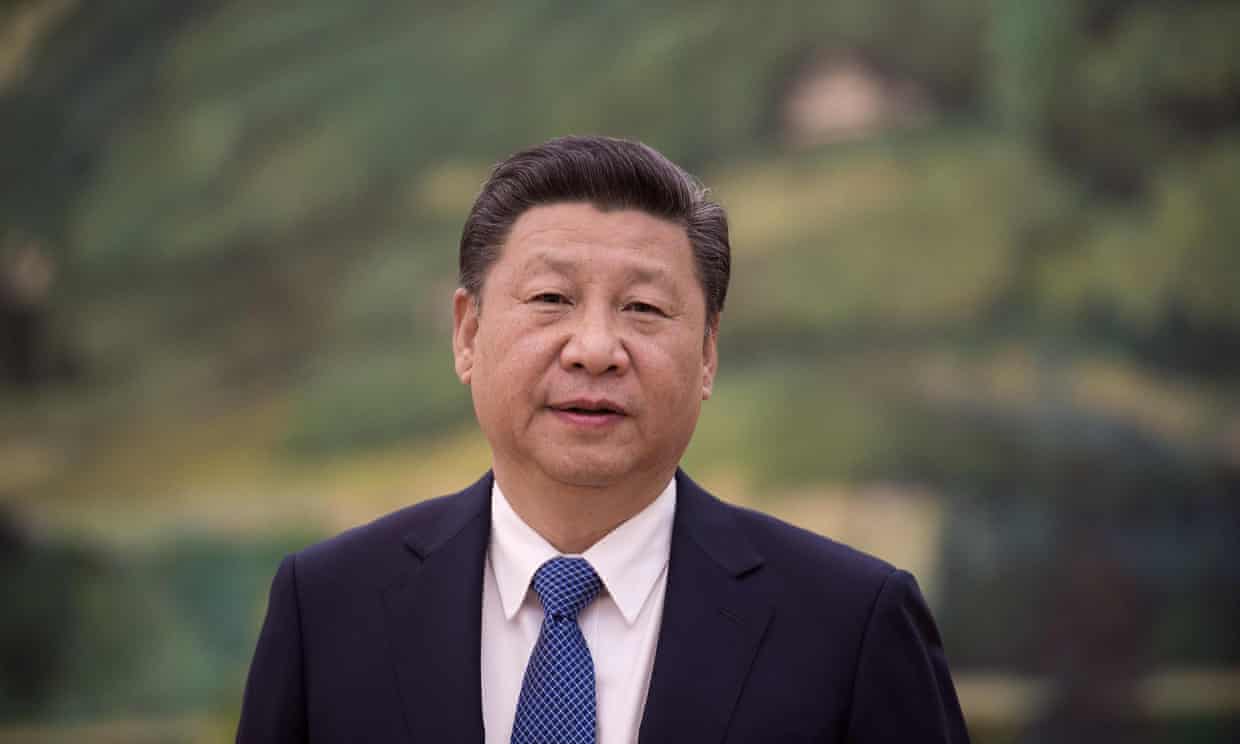

The report throws the spotlight on to President Xi Jinping’s war on corruption, which has punished more than a million Communist party officials since 2013. Xi has said fighting corruption is “a matter of life and death” but many experts characterise the campaign as a political purge against members of rival factions.

The opaque extralegal detention system is used by anti-corruption officials to hold suspects indefinitely until they confess. At least 11 have died while in the custody of the country’s widely feared Commission for Discipline Inspection.

“President Xi has built his anti-corruption campaign on an abusive and illegal detention system,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

“Torturing suspects to confess won’t bring an end to corruption but will end any confidence in China’s judicial system.”

All of China’s 88 million Communist party members can be subject to detention or shuanggui, which in Chinese means to report at a designated time and place, where suspects are held incommunicado and often in padded, windowless rooms.

“If you sit, you have to sit for 12 hours straight; if you stand, then you have to stand for 12 hours as well. My legs became swollen and my buttocks were raw and started oozing pus,” a former detainee is quoted as saying in the report. Names were withheld for fear of government reprisals.

Others have described detention simply as a “living hell”. It is extremely rare for those who have been through the system to speak openly.

In one account a detainee was kept awake for 23 hours a day, forced to stand the entire time and balance a book on his head, one lawyer said. After eight days he confessed “to whatever they said” and was then allowed to sleep for two hours a day.

While Xi champions his anti-corruption drive, he has also advocated enhancing China’s “rule of law”, but activists say the two concepts are completely at odds when suspects are tortured and forced to confess.

Although the anti-corruption campaign is technically separate from China’s judicial system, Human Rights Watch documented cases where prosecutors worked alongside corruption investigators, using the shuanggui system to gather evidence. After the extralegal detention, cases are usually transferred to the courts, where there is a 99.92% conviction rate.

“In shuanggui corruption cases the courts function as rubber stamps, lending credibility to an utterly illegal Communist party process,” Richardson said. “Shuanggui not only further undermines China’s judiciary – it makes a mockery of it.”

Those sentiments have been echoed by western governments as Xi has ramped up his anti-corruption push and use of the system has skyrocketed.

Shuanggui “operates without legal oversight” and suspects are “in some cases tortured”, the US State Department wrote in its annual human rights report on China. Some confessions extracted in detention were eventually overturned by courts, the US government report said.

Government officials are the majority of suspects disappeared into the system, but bankers, university administrators, entertainment industry figures and any other Communist party member can be detained.

Human Rights Watch called for shuanggui to be abolished, adding that successfully fighting corruption required “robust protections for the rights of suspects”.

“Eradicating corruption won’t be possible so long as the shuanggui system exists,” Richardson said. “Every day this system threatens the lives of party members and underscores the abuses inherent in President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Benjamin Haas

The report throws the spotlight on to President Xi Jinping’s war on corruption, which has punished more than a million Communist party officials since 2013. Xi has said fighting corruption is “a matter of life and death” but many experts characterise the campaign as a political purge against members of rival factions.

The opaque extralegal detention system is used by anti-corruption officials to hold suspects indefinitely until they confess. At least 11 have died while in the custody of the country’s widely feared Commission for Discipline Inspection.

“President Xi has built his anti-corruption campaign on an abusive and illegal detention system,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

“Torturing suspects to confess won’t bring an end to corruption but will end any confidence in China’s judicial system.”

All of China’s 88 million Communist party members can be subject to detention or shuanggui, which in Chinese means to report at a designated time and place, where suspects are held incommunicado and often in padded, windowless rooms.

“If you sit, you have to sit for 12 hours straight; if you stand, then you have to stand for 12 hours as well. My legs became swollen and my buttocks were raw and started oozing pus,” a former detainee is quoted as saying in the report. Names were withheld for fear of government reprisals.

Others have described detention simply as a “living hell”. It is extremely rare for those who have been through the system to speak openly.

In one account a detainee was kept awake for 23 hours a day, forced to stand the entire time and balance a book on his head, one lawyer said. After eight days he confessed “to whatever they said” and was then allowed to sleep for two hours a day.

While Xi champions his anti-corruption drive, he has also advocated enhancing China’s “rule of law”, but activists say the two concepts are completely at odds when suspects are tortured and forced to confess.

Although the anti-corruption campaign is technically separate from China’s judicial system, Human Rights Watch documented cases where prosecutors worked alongside corruption investigators, using the shuanggui system to gather evidence. After the extralegal detention, cases are usually transferred to the courts, where there is a 99.92% conviction rate.

“In shuanggui corruption cases the courts function as rubber stamps, lending credibility to an utterly illegal Communist party process,” Richardson said. “Shuanggui not only further undermines China’s judiciary – it makes a mockery of it.”

Those sentiments have been echoed by western governments as Xi has ramped up his anti-corruption push and use of the system has skyrocketed.

Shuanggui “operates without legal oversight” and suspects are “in some cases tortured”, the US State Department wrote in its annual human rights report on China. Some confessions extracted in detention were eventually overturned by courts, the US government report said.

Government officials are the majority of suspects disappeared into the system, but bankers, university administrators, entertainment industry figures and any other Communist party member can be detained.

Human Rights Watch called for shuanggui to be abolished, adding that successfully fighting corruption required “robust protections for the rights of suspects”.

“Eradicating corruption won’t be possible so long as the shuanggui system exists,” Richardson said. “Every day this system threatens the lives of party members and underscores the abuses inherent in President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Benjamin Haas

No comments:

Post a Comment