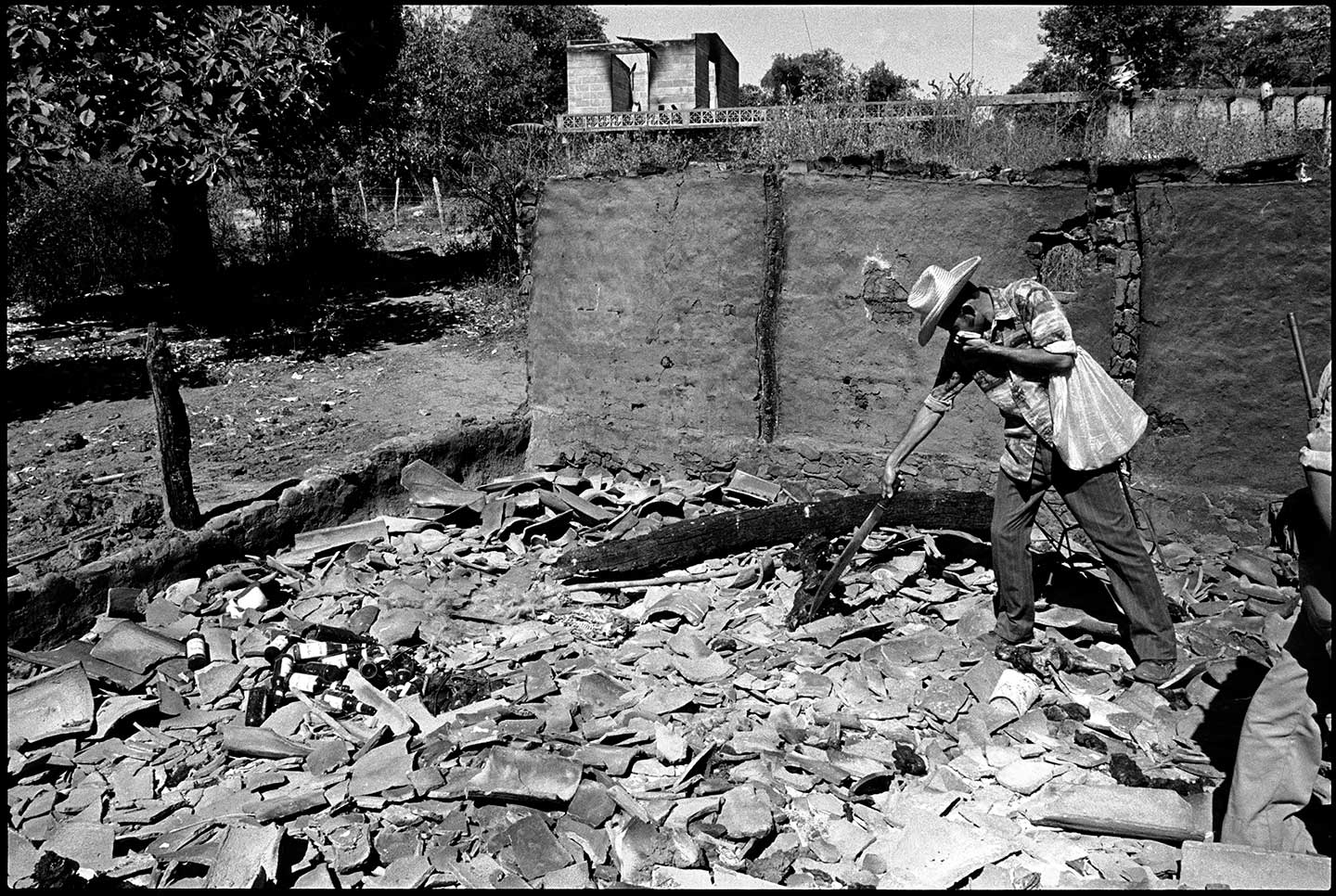

Cerro Pando, El Salvador—Five days after the massacre, Trinidad Ramírez returned to his childhood home to bury his mother, sister, brother, 8-year-old niece, and 6-year-old nephew. He and two other men dug a meter-deep hole at the foot of a sapote tree. They wrapped the charred bodies in sheets and curtains and said a hasty prayer. Then they fled. There were still soldiers around.

Ramírez had been working as a field hand farther down the mountain, trying to survive an increasingly bloody civil war between leftist guerrillas and right-wing government troops. It was December 1981. The United States was sending the Salvadoran military a million dollars a day. Soldiers killed Ramírez’s family and nearly 1,000 other civilians—mostly women, children, and old people—in a scorched-earth operation in El Mozote, La Joya, Cerro Pando, and surrounding villages in the department of Morazán. It was the worst massacre in modern Latin American history.

The government denied the slaughter, and the Reagan administration repeated the lie, dismissing accounts by journalists Raymond Bonner and Alma Guillermoprieto in The New York Times and The Washington Post, respectively. Pictures of rotting bodies and burnt homes by photographer Susan Meiselas accompanied the stories, which were both published on January 27, 1982. After the war ended a decade later, a UN Truth Commission pressured the Salvadoran government to excavate the ruins of El Mozote’s sacristy, where they found the skulls of 143 individuals. All but 12 were children. Investigative journalist Mark Danner reviewed hundreds of State Department and CIA cables to expose the US cover-up in The New Yorker. Embassy officials had known about the scorched-earth operation in Morazán carried out by the US-trained Atlacatl battalion; the officials visited the devastated area on January 30 and got the impression from interviews that “something horrible had happened.” They played it down in cables to Washington. The State Department denied the massacre to Congress. Danner’s 1993 article, “The Truth of El Mozote,” set the record straight: It happened. The United States knew.

On the thirty-fifth anniversary of the atrocity, El Mozote remains a stark example of the tragic consequences of anti-communist fervor in poor countries like El Salvador. But outside history classes that study the country’s civil war and journalism classes that assign Danner’s article (later expanded into a book), the massacre has mostly been forgotten. There are new ideologies and new atrocities to worry about.

But in El Mozote, where recent developments—an international court sentence, a renewed investigation—have whittled away at decades of fear and silence, people are just beginning to speak openly about what happened there three and a half decades ago. Poverty and PTSD are widespread, and government attention to the community, in the country’s poor and war-torn rural northeast, is scarce. But change is palpable. The village is starting to accept what American journalists long ago concluded about the massacre; people are accepting that version of history, and writing their own.

In the early years after the war, many Salvadorans just wanted to forget. Families who returned from refugee camps found their houses destroyed, their fields barren, and their neighbors equally desperate. An amnesty law passed in 1993 halted the investigation into the massacre, eliminating the possibility of justice or reparations. In the absence of official truth (or access to foreign media), people in El Mozote argued over whether the army or the guerrillas were at fault. Many residents had fled before the massacre and spent the war in parts of the country controlled by the military. They learned false versions of what had happened back home: that the guerillas had done the killing, or that it was the army but the victims were guerrillas at a training camp. The sacristy exhumation left no doubt that the victims were civilians, but many El Mozote residents still blamed the guerrillas for provoking the army’s wrath. A small group of survivors tried to convince people of the military’s full responsibility—among them Rufina Amaya, who’d escaped death by hiding beneath a crabapple tree while soldiers killed her husband and four young children—but most people were too traumatized to talk. When international reporters went home after the truncated investigation, silence enveloped the village. It stayed that way for years.

Then, around 2008, a British nun and a Belgian priest spearheaded a fight for justice in the international realm. The amnesty law had extinguished the case in the Salvadoran courts, but the Inter-American Court of Human Rights had agreed to hear it. The nun, Anne Griffin, crisscrossed the country with Spanish psychologist Sol Yañez to conduct hundreds of interviews in preparation for the hearing in the spring of 2012. “The majority of people were talking for the first time,” Griffin told me. “Ninety-five percent cried like it happened yesterday.”

In October 2012, the Inter-American Court found El Salvador guilty of committing the massacre, covering it up, and failing to investigate after the war. The Court ordered the government to re-open the case, punish the perpetrators, and compensate victims’ relatives. The ruling has brought tokens of government aid to El Mozote—instruments for the cultural center, plaques for the memorial—but more importantly, it has united the splintered community of family members. Several dozen of them meet on a monthly basis to plan their continued fight for recognition.

This July, in an unexpected twist, El Salvador’s Supreme Court declared the amnesty law unconstitutional. In September, a judge re-opened the archived case against the massacre’s culprits. Government investigators have spent the past month exhuming graves—among them, the shallow hole in Cerro Pando where Ramírez buried his five relatives—though political resistance and legal obstacles abound.

Nowadays, El Mozote is a bustling village with 151 houses, a tiny clinic, and a cellphone tower. It’s poor and remote—the government has never bothered to pave five kilometers of dirt road that wash away each year during the rainy season—but it no longer feels like a ghost town. On Saturday, hundreds of Salvadorans gathered in the village to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the massacre. The yearly event used to be run by the FMLN, the political party formed by the guerrillas after the war, and half the town would stay at home, upset by the “politicization” of their suffering. Now the victims’ association organizes the ceremony, which included a theatrical performance by village children, a Catholic mass, and speeches by family members of people who died in the massacre.

When I started reporting in El Mozote four years ago, local tour guides told a version of the story that came from Danner’s book—chopped up, translated into Spanish, and recounted so many times it resembled little more than a shopping list of gruesome anecdotes: the smell of burning flesh; the screams of young girls being raped; the whimper of a baby tossed onto a bayonet.

Now it’s more common to hear people tell their own stories. “Over time, the fear has dissipated,” says Wilfredo Medrano, a lawyer who has represented El Mozote victims for more than two decades. “People use their own language now.”

Paula Portillo, Trinidad Ramírez’s sister-in-law, lived down the hill from where soldiers marched through Cerro Pando in December 1981. She and her husband locked themselves and their five children in their one-room home. “We heard everything,” she told me. After the gunshots faded, she climbed the hill and saw the bodies of her relatives. “I went home and went straight to bed,” she said. “We never told the children.” These personal stories are similar in content to the guides’ anecdotes—violent, vivid, heartbreaking—but different in tone. They’re part of a string of quotidian memories that start before the massacre and stretch into the present. They’re not recited, but relived.

Portillo’s family struggled to get by after the massacre, fleeing from soldiers and stigma, and they struggle to get by now. The same is true for most families from northern Morazán. There was little economic aid after the war, and only close relatives qualify for the reparations ordered by the Inter-American Court. Grandchildren, nieces and nephews, and siblings-in-law usually don’t count. Over the past two years the government has distributed nearly $2 million to next-of-kin, but there are so many recipients, the maximum any individual has received is only $20,000. Some have used the money for home improvements—an indoor toilet, a new roof. Others have paid off debts. Still others have stashed the money under their couch, wasted it on alcohol, or hired a coyote to smuggle their children into the United States.

“The sentence was supposed to be a metamorphosis,” Medrano said. “But people’s lives haven’t changed much.”

In some cases, the money has created conflict. Fighting over scraps is a characteristic of poverty, but it’s also a result of decades of impunity, abandonment, and trauma. When I visited El Mozote in July 2013, before the checks were distributed, the victims’ association was upset because the Catholic Church had stuck a lock on the gate to the “Garden of the Innocents,” where remains of the 143 children exhumed in 1992 are buried. The church was upset because local guides had been bringing tourists into the garden and collecting tips (a dollar or two) without making a contribution to the church. The skirmish never got resolved; the garden remains locked, except on the anniversary of the massacre.

Every year at the ceremony, Medrano gives a speech urging the community not to be appeased by the trickle of government aid. “Truth, reparations, and justice is what we’re fighting for,” he says.

This year, for the first time since 1993, a Salvadoran judge opened a case against 13 military officers accused of participating in the massacre. But the judge, Jorge Guzmán, decided not to order the officers’ arrest, raising questions about his intent to pursue unbiased justice. Guzmán claims he lacks sufficient evidence, but over the past month, investigators have exhumed the remains of at least 43 individuals in seven separate graves. Their reports will be added to the case file, alongside evidence of 36 skeletons exhumed in April 2015, 143 skulls excavated in 1992, and the remains of several hundred people unearthed between 1993 and 2011.

On Saturday, two open exhumation sites sat behind yellow police tape ten meters from the center of El Mozote in plain view of the stage where the anniversary ceremony took place. Government officials giving speeches, journalists filming the act, and Salvadorans watching on television saw a different message from years past: This is not a relic of the past. It’s a crime scene.

On November 30, Trinidad Ramírez led a group of prosecutors, police detectives, and forensic anthropologists to the sapote tree. Barely taller than him in 1981, it now towered over the other trees on the hilltop, providing shade as the investigators picked up their shovels and broke ground. Ramírez stood at the edge of the worksite beside his sister-in-law, Paula Portillo, and his brother-in-law, Antonio Castro, the father of the two children killed here 35 years ago.

Ramírez, now 74 years old, paced back and forth. He took his straw hat off and put it back on. “I don’t know if they’ll still be here after all these years,” he said.

The anthropologists sifted through layer after layer of dirt. Then: a hint of blue. A tiny sandal. “My daughter’s,” Castro said. Over the next week, one by one, five skeletons emerged, intertwined with the roots of the sapote.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: Sarah Esther Maslin

Ramírez had been working as a field hand farther down the mountain, trying to survive an increasingly bloody civil war between leftist guerrillas and right-wing government troops. It was December 1981. The United States was sending the Salvadoran military a million dollars a day. Soldiers killed Ramírez’s family and nearly 1,000 other civilians—mostly women, children, and old people—in a scorched-earth operation in El Mozote, La Joya, Cerro Pando, and surrounding villages in the department of Morazán. It was the worst massacre in modern Latin American history.

The government denied the slaughter, and the Reagan administration repeated the lie, dismissing accounts by journalists Raymond Bonner and Alma Guillermoprieto in The New York Times and The Washington Post, respectively. Pictures of rotting bodies and burnt homes by photographer Susan Meiselas accompanied the stories, which were both published on January 27, 1982. After the war ended a decade later, a UN Truth Commission pressured the Salvadoran government to excavate the ruins of El Mozote’s sacristy, where they found the skulls of 143 individuals. All but 12 were children. Investigative journalist Mark Danner reviewed hundreds of State Department and CIA cables to expose the US cover-up in The New Yorker. Embassy officials had known about the scorched-earth operation in Morazán carried out by the US-trained Atlacatl battalion; the officials visited the devastated area on January 30 and got the impression from interviews that “something horrible had happened.” They played it down in cables to Washington. The State Department denied the massacre to Congress. Danner’s 1993 article, “The Truth of El Mozote,” set the record straight: It happened. The United States knew.

On the thirty-fifth anniversary of the atrocity, El Mozote remains a stark example of the tragic consequences of anti-communist fervor in poor countries like El Salvador. But outside history classes that study the country’s civil war and journalism classes that assign Danner’s article (later expanded into a book), the massacre has mostly been forgotten. There are new ideologies and new atrocities to worry about.

But in El Mozote, where recent developments—an international court sentence, a renewed investigation—have whittled away at decades of fear and silence, people are just beginning to speak openly about what happened there three and a half decades ago. Poverty and PTSD are widespread, and government attention to the community, in the country’s poor and war-torn rural northeast, is scarce. But change is palpable. The village is starting to accept what American journalists long ago concluded about the massacre; people are accepting that version of history, and writing their own.

In the early years after the war, many Salvadorans just wanted to forget. Families who returned from refugee camps found their houses destroyed, their fields barren, and their neighbors equally desperate. An amnesty law passed in 1993 halted the investigation into the massacre, eliminating the possibility of justice or reparations. In the absence of official truth (or access to foreign media), people in El Mozote argued over whether the army or the guerrillas were at fault. Many residents had fled before the massacre and spent the war in parts of the country controlled by the military. They learned false versions of what had happened back home: that the guerillas had done the killing, or that it was the army but the victims were guerrillas at a training camp. The sacristy exhumation left no doubt that the victims were civilians, but many El Mozote residents still blamed the guerrillas for provoking the army’s wrath. A small group of survivors tried to convince people of the military’s full responsibility—among them Rufina Amaya, who’d escaped death by hiding beneath a crabapple tree while soldiers killed her husband and four young children—but most people were too traumatized to talk. When international reporters went home after the truncated investigation, silence enveloped the village. It stayed that way for years.

Then, around 2008, a British nun and a Belgian priest spearheaded a fight for justice in the international realm. The amnesty law had extinguished the case in the Salvadoran courts, but the Inter-American Court of Human Rights had agreed to hear it. The nun, Anne Griffin, crisscrossed the country with Spanish psychologist Sol Yañez to conduct hundreds of interviews in preparation for the hearing in the spring of 2012. “The majority of people were talking for the first time,” Griffin told me. “Ninety-five percent cried like it happened yesterday.”

In October 2012, the Inter-American Court found El Salvador guilty of committing the massacre, covering it up, and failing to investigate after the war. The Court ordered the government to re-open the case, punish the perpetrators, and compensate victims’ relatives. The ruling has brought tokens of government aid to El Mozote—instruments for the cultural center, plaques for the memorial—but more importantly, it has united the splintered community of family members. Several dozen of them meet on a monthly basis to plan their continued fight for recognition.

This July, in an unexpected twist, El Salvador’s Supreme Court declared the amnesty law unconstitutional. In September, a judge re-opened the archived case against the massacre’s culprits. Government investigators have spent the past month exhuming graves—among them, the shallow hole in Cerro Pando where Ramírez buried his five relatives—though political resistance and legal obstacles abound.

Nowadays, El Mozote is a bustling village with 151 houses, a tiny clinic, and a cellphone tower. It’s poor and remote—the government has never bothered to pave five kilometers of dirt road that wash away each year during the rainy season—but it no longer feels like a ghost town. On Saturday, hundreds of Salvadorans gathered in the village to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the massacre. The yearly event used to be run by the FMLN, the political party formed by the guerrillas after the war, and half the town would stay at home, upset by the “politicization” of their suffering. Now the victims’ association organizes the ceremony, which included a theatrical performance by village children, a Catholic mass, and speeches by family members of people who died in the massacre.

When I started reporting in El Mozote four years ago, local tour guides told a version of the story that came from Danner’s book—chopped up, translated into Spanish, and recounted so many times it resembled little more than a shopping list of gruesome anecdotes: the smell of burning flesh; the screams of young girls being raped; the whimper of a baby tossed onto a bayonet.

Now it’s more common to hear people tell their own stories. “Over time, the fear has dissipated,” says Wilfredo Medrano, a lawyer who has represented El Mozote victims for more than two decades. “People use their own language now.”

Paula Portillo, Trinidad Ramírez’s sister-in-law, lived down the hill from where soldiers marched through Cerro Pando in December 1981. She and her husband locked themselves and their five children in their one-room home. “We heard everything,” she told me. After the gunshots faded, she climbed the hill and saw the bodies of her relatives. “I went home and went straight to bed,” she said. “We never told the children.” These personal stories are similar in content to the guides’ anecdotes—violent, vivid, heartbreaking—but different in tone. They’re part of a string of quotidian memories that start before the massacre and stretch into the present. They’re not recited, but relived.

Portillo’s family struggled to get by after the massacre, fleeing from soldiers and stigma, and they struggle to get by now. The same is true for most families from northern Morazán. There was little economic aid after the war, and only close relatives qualify for the reparations ordered by the Inter-American Court. Grandchildren, nieces and nephews, and siblings-in-law usually don’t count. Over the past two years the government has distributed nearly $2 million to next-of-kin, but there are so many recipients, the maximum any individual has received is only $20,000. Some have used the money for home improvements—an indoor toilet, a new roof. Others have paid off debts. Still others have stashed the money under their couch, wasted it on alcohol, or hired a coyote to smuggle their children into the United States.

“The sentence was supposed to be a metamorphosis,” Medrano said. “But people’s lives haven’t changed much.”

In some cases, the money has created conflict. Fighting over scraps is a characteristic of poverty, but it’s also a result of decades of impunity, abandonment, and trauma. When I visited El Mozote in July 2013, before the checks were distributed, the victims’ association was upset because the Catholic Church had stuck a lock on the gate to the “Garden of the Innocents,” where remains of the 143 children exhumed in 1992 are buried. The church was upset because local guides had been bringing tourists into the garden and collecting tips (a dollar or two) without making a contribution to the church. The skirmish never got resolved; the garden remains locked, except on the anniversary of the massacre.

Every year at the ceremony, Medrano gives a speech urging the community not to be appeased by the trickle of government aid. “Truth, reparations, and justice is what we’re fighting for,” he says.

This year, for the first time since 1993, a Salvadoran judge opened a case against 13 military officers accused of participating in the massacre. But the judge, Jorge Guzmán, decided not to order the officers’ arrest, raising questions about his intent to pursue unbiased justice. Guzmán claims he lacks sufficient evidence, but over the past month, investigators have exhumed the remains of at least 43 individuals in seven separate graves. Their reports will be added to the case file, alongside evidence of 36 skeletons exhumed in April 2015, 143 skulls excavated in 1992, and the remains of several hundred people unearthed between 1993 and 2011.

On Saturday, two open exhumation sites sat behind yellow police tape ten meters from the center of El Mozote in plain view of the stage where the anniversary ceremony took place. Government officials giving speeches, journalists filming the act, and Salvadorans watching on television saw a different message from years past: This is not a relic of the past. It’s a crime scene.

On November 30, Trinidad Ramírez led a group of prosecutors, police detectives, and forensic anthropologists to the sapote tree. Barely taller than him in 1981, it now towered over the other trees on the hilltop, providing shade as the investigators picked up their shovels and broke ground. Ramírez stood at the edge of the worksite beside his sister-in-law, Paula Portillo, and his brother-in-law, Antonio Castro, the father of the two children killed here 35 years ago.

Ramírez, now 74 years old, paced back and forth. He took his straw hat off and put it back on. “I don’t know if they’ll still be here after all these years,” he said.

The anthropologists sifted through layer after layer of dirt. Then: a hint of blue. A tiny sandal. “My daughter’s,” Castro said. Over the next week, one by one, five skeletons emerged, intertwined with the roots of the sapote.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: Sarah Esther Maslin

No comments:

Post a Comment