In his youthful second book, an enthusiastically received novel called The Romantics (2000), Pankaj Mishra portrays young men from provincial India who immerse themselves in modern intellectual history. Like many students from the provinces before him, Mishra’s main character seeks his place largely through reading. But unlike those earlier generations, he explores who to become not just in his new city, but in globalized modernity.

Mishra’s hero reads Gustave Flaubert’s coming-of-age novel, Sentimental Education, and Edmund Wilson’s interpretation of it as a commentary on exclusion and its consequences. He shares his reading with a more politically aware friend, almost embarrassed by his own bookishness. But when they meet again years later, it turns out that his friend has taken Wilson’s essay very seriously. For in nineteenth-century Europe and its struggles, he discovered an environment much like his own. Although a new world of moral and material possibilities seemed to open up before the young men of his generation, now, as then, only a few would actually succeed in their strivings. Flaubert captured the mismatch that a modern youth experienced between “large, passionate, but imprecise longings” and the “slow, steady shrinking of horizons.” The European bildungsroman addressed what has become a worldwide situation in our time.

Mishra’s novel went on to diagnose the consequences of such a mismatch. After the students witness some rioting on campus, the friend explains with “a new vehemence” that the perpetrators were mainly “young men with nothing to do, nowhere to go, with no future, no prospects, nothing, nothing at all.” The bookish young man is clearly Mishra in another guise, down to their common birth year and education. His friend, who is more familiar, not simply with politics but also with criminality and violence, is also based on a real person; they met the year Mishra moved from Allahabad to Benares and fell in love himself with the literary criticism of Edmund Wilson. Mishra has not published another novel since. But in his admirable career writing on politics, he closely identifies with the lesson of his erstwhile friend (who later became a contract killer): If people are exposed to grandeur and then their horizons shrink, the results can prove dangerous.

While Mishra long ago recognized the uses of Western thought in understanding the causes of global rage, in his new book, Age of Anger, he turns to intellectual history to counter civilizational or theological explanations for that rage in its more recent forms. After September 11, 2001, a crew of specialists arose to designate Islam the cause of hatred and violence; their essential goal was to immunize our own way of life from blame and scrutiny. Such analysts could never anticipate how their own states and cultures gave rise to a broader discontent—including in Europe and the United States. After votes for Brexit and Donald Trump, it turns out it was not just “radicalized” Muslim youths who resented elites and resorted to violence as a means of revenge.

Instead, Mishra argues that the European past was a dry run for our global present. In the German and Russian populists and terrorists of the nineteenth century, Mishra finds avatars of the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, and the Muslim radical preacher Anwar al-Awlaki. In the “Frenchmen who bombed music halls, cafés, and the Paris stock exchange” in the 1880s and ’90s, he sees forerunners of today’s “English and Chinese nationalists, Somali pirates, human traffickers, and anonymous cyber-hackers.” Understanding political and economic inequality is vital to understanding these convulsions; but we also have to examine how the ideals we live with—of capitalism and liberalism—have long produced unbearable disillusionment. To grasp the fear and desire behind violent reaction, Mishra contends, we need not just Karl Marx and Thomas Piketty, but also analysts of the psyche and spirit.

Age of Anger traces today’s discontent back to the beginning of modernity, when Europe underwent commercial and, later, industrial revolutions, toppled its aristocratic elites and sometimes kings, and trumpeted freedom and equality, even as it redoubled the prestige of luxury and the lure of hierarchy. It was the start of the process of building a world of plenty and self-transformation, but also of distinction and envy. Philosophers of the eighteenth century diagnosed the likely outcome of this divide; the nineteenth century experienced that outcome, in furious, violent responses to it.

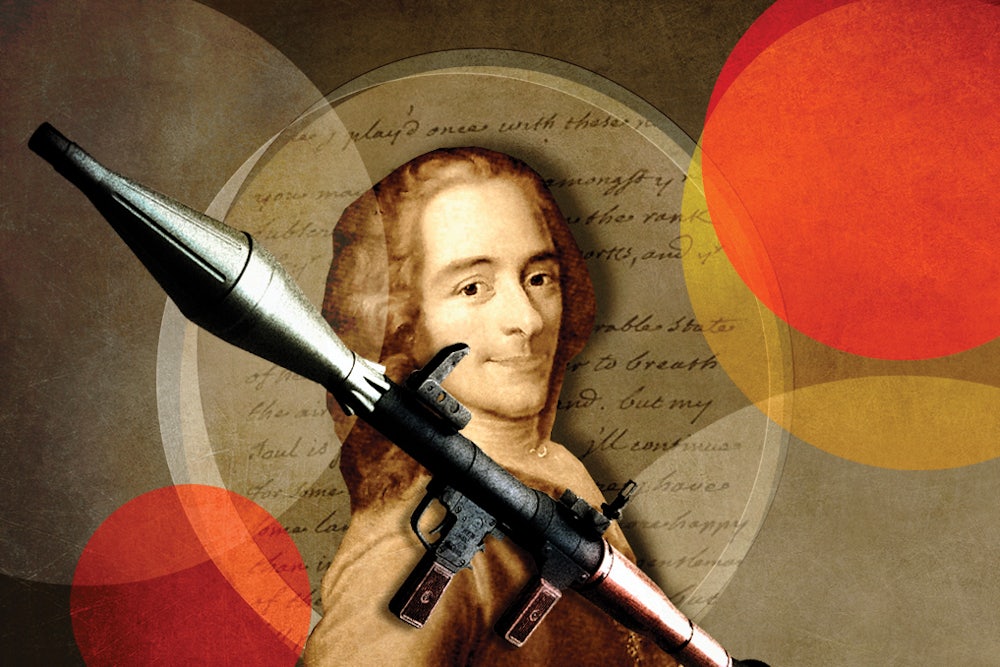

Mishra starts with a set piece on Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who offer us two opposing views of modernity and how to think about its shortcomings. Voltaire, the mainstream rationalist, embraced commerce and progress; he saw little daylight between the celebration of the one and the inevitability of the other. He endorsed individual freedom and pluralistic tolerance up to a point. Compared to the democratic mob, hereditary rulers—especially if well tutored by freethinkers like Voltaire himself—were less likely to become oppressive. He held a low opinion of Rousseau, the rebellious son of a Genevan watchmaker. Rousseau returned the compliment, writing to Voltaire in 1760, “I hate you.”

Rousseau, on the other hand, thought modernity was bringing about not progress but tragedy. Modern men and women learned to envy the magnificence of the winners and to define their ends in a triangular process of assessing what others valued first. In his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Rousseau depicted how enraging it is to subordinate oneself to the desires of others, in a state of exclusion from Voltaire’s opulent civilization. Because Rousseau had experienced the life of a social climber himself, he understood “the many uprooted men” who failed to “adapt themselves to a stable life in society,” and began to see that failure as the product of a larger “injustice against the human race.” Enslaved by manufactured desires, most Europeans experienced merely the frustration of never seeing them realized. Commercial modernity imprisoned the rich as much as the poor in a syndrome of “envy, fascination, revulsion, and rejection.”

It is Voltaire’s vision of modernity, however, that has been the more seductive one throughout much of history. His theory fueled the first age of globalization before World War I, and has gained currency again in the enthusiasm for markets that burgeoned after the end of the Cold War. “As Louis Vuitton opened in Borneo,” Mishra observes sarcastically, “it seemed only a matter of time before the love of luxury was followed by the rule of law, the enhanced use of critical reason, and the expansion of individual freedom.” But in part because the results benefit only a few, in part because modernity is a cage for everyone, Rousseau’s heirs await the moment to strike.

The question is: What are those left behind to do with their frustration? They can convert it, as Rousseau did, into insight into the limits of modernity, even for those who win the game. Or, sensing that there will be no chance of winning for all, especially as the competition goes global, they can wreak vengeance on the system.

Mishra sees an early example of such revenge in the German Romantics, whom he calls “the first angry young nationalists.” By the start of the nineteenth century, Germany—decades away from industrial modernity or even political unity—had failed to keep pace with the power and wealth that made Britain and France so opulent. Educated young Germans shared a sense of being belated, peripheral, and weak. They looked to France as “the home of the worldly, elegant, and sensuous philosopher, who spoke a language of unparalleled clarity and precision.” Yet when they arrived there, they perceived the same shallowness that Rousseau had seen before them. In 1769, the incisive philosopher J.G. Herder set out from the Baltic port of Riga to Paris, hoping to become gallicized. He left the next year, acutely disappointed, and convinced of the need to formulate a sturdy alternative to what he saw as hollow cosmopolitanism.

Building on Rousseau, German poets and philosophers such as Herder and Friedrich Schiller introduced a profound diagnosis of their own alienation. A feeling of being divided from the world, and even from one’s very self—as well as from one’s own work, as their follower Karl Marx added—was the worst thing about modern consciousness. Along with J.G. Fichte, Herder proposed a nationalist cure for this sense of estrangement. Herder extolled the popular genius of German Kultur, as well as the ineffability of particular cultures across the board. It was the opposite of the French idea of civilisation. Instead of seeking justification for their culture in progress and the promise of the future, Germans looked to the distant past to confirm their sense of national greatness, elevating folklore and myths to the pinnacle of high art. Whereas civilisation was centered on commerce, luxury, and urbanity, Kultur infused local ties and traditions with fervent spirituality, and idealized the Volk.

In the nineteenth century, such ideas drove German unification and national awakenings across Europe, and found their nadir in Adolf Hitler’s Germany in the twentieth century. Not only did nationalism give the world’s peasantries an outlet for their rage, but it now tempts those countries once at the apex of civilization toward populism. The Brexit vote and Trump’s unexpected win illustrate that when stagnation sets in at the center, anger can drive nationalist backlash. A nostalgia for “little England” takes revenge on cosmopolitan and diverse London, while calls to “make America great again” imply xenophobic and militaristic policies. Even Voltaire’s France is now a battleground in liberalism’s fight for survival against explosive nationalist resentment.

Mishra also lavishes attention on Russia, the first global hinterland where the Enlightenment’s liberatory wave crashed against the wall of a massive peasantry—sparking the invention of nihilism and terrorism. Since the Enlightenment, Russia’s ruling class had debated whether to westernize, and foreign kibitzers were divided over whether and how to extend civilization to Russia’s feudal society of aristocrats and serfs. (While Rousseau doubted it made sense to “tutor” Russia, Voltaire advised Empress Catherine the Great, and she bought his library after he died, hoping it would help.) But as the nineteenth century dragged on, autocratic rule did not bring forth progress fast enough to forestall its critics.

When you start so far behind, the very attempt to catch up breeds self-hatred. Your “conscience murmurs,” Fyodor Dostoevsky lamented, that you are “a hollow man,” condemned in advance to a “state of insatiable, bilious malice.” But whereas Dostoevsky only wrote about this discontent, other Russians took the route of terroristic deeds. The activist and thinker Mikhail Bakunin argued for the need to bring the system down in one swift stroke; he believed that “heroic acts” could “transform the world from an authoritarian cage into an arcadia of human freedom.” Battling against Marx for intellectual leadership of Europe’s working classes, Bakunin spawned a countercultural tradition of “lethal individualism,” whereby vivid destruction, instead of patient creation, would serve to define a self. His fellow critics of capitalism and empire were transnational. They bombed cities and assassinated political leaders across the Atlantic, inaugurating “the first phase of global jihad,” and anticipating the long-distance networks of lone wolves and terrorist cells of today.

“Large parts of Asia and Africa,” Mishra concludes, “are now plunging deeper” into their own “fateful experience of that modernity.” They are told they live on a flat earth, but find it impossible to claw their way forward on what feels like a vertical cliff of hierarchy. Westernization destroyed existing beliefs and institutions in these countries, promoting instead a culture of individual freedoms and rights. But, as Mishra points out, “Most newly created ‘individuals’ toil within poorly imagined social and political communities and/or states with weakening sovereignty,” narrowing the opportunities for personal flourishing. Western modernity opens up fault lines that “run through human souls as well as nations and societies undergoing massive change.” Out of the gap between expected liberation and experienced limits, fury boils.

A self-proclaimed history of the present, Age of Anger also feels like a blast from the past. In its literacy and literariness, it has the feel of Edmund Wilson’s extraordinary dramas of modern ideas—books like To the Finland Station—but with a different endpoint and a more global canvas. Mishra reads like a brilliant autodidact, putting to shame the many students who dutifully did the reading for their classes but missed the incandescent fire and penetrating insight in canonical texts. Yet his narrative of the outcasts of modernity has been told before, at different times and with different emphases, to explain earlier episodes of revolt and revolution: He is not the first to locate the origins of fascism in nineteenth-century German malcontents, and it was once popular to tag Rousseau for paving the way for communism and the student movement.

Nor is Mishra ready to offer solutions. Though he looks at the bleak record of commercial modernity in propagating itself across the world and marks its self-defeating expansion, he holds out no defined alternative. It is unclear whether Mishra feels the chief flaw lies in modernity’s failures—its false promise to liberate everyone—or in its successes, and the devastation that has accompanied them.

Of course, true freedom and equality beckon, which is why Mishra shows an occasional soft spot for lone wolves—including Timothy McVeigh—who hope a spectacular blow will shatter the glass. But ultimately, he does not hold up such anarchists as models. Indeed, even though they unceremoniously dismiss the “gaudy cult of progress,” it seems to Mishra nonetheless that “the men trying to radicalize the liberal principle of freedom and autonomy, of individual power and agency, seem more rootless and desperate than before.” In a world that can no longer count on progress, and that fears its consequences for the planet, Mishra praises Pope Francis’s exemplary moral stances on behalf of the environment and the poor—if only because no one else is offering hope. Yet he also acknowledges there is no going back to a premodern metaphysics or economy, when ambition has come to seem everyone’s birthright, first in Europe, later everywhere.

If intellectual history matters in this parlous situation, then getting Rousseau right does, too. Interpreting him, as Mishra does, as nostalgic for ancient liberty or protective of interior freedom in the face of the modern catastrophe, will ultimately not work. After all, Rousseau also rejected the viability of reviving the Sparta he sometimes idealized. For that reason, he thought carefully about how to bring about free communities of equals in our economic and political circumstances.

And he also wrote The Social Contract, a text Mishra barely addresses. After reading The Social Contract’s commitment to modern freedom and equality, a fellow Enlightenment thinker, Immanuel Kant, early saw that Rousseau’s main impulses between a lamentation for modernity and an emancipatory program for it have to be reconciled at all costs. There is no way to sever Rousseau’s critique of painful exclusion and “glittering misery”—now, as Mishra shows, applicable across the world and into its smallest byways—from a political attempt to answer it.

“Rousseau,” Kant remarked, “was not far wrong in preferring the state of savages—so long, that is, as the last stage to which the human race must climb is not attained.” Starting from his remote corner in the Benares library reading Edmund Wilson, no one has discerned better than Mishra just how far we still are from the top.

Original Article

Source: newrepublic.com/

Author: Samuel Moyn

Mishra’s hero reads Gustave Flaubert’s coming-of-age novel, Sentimental Education, and Edmund Wilson’s interpretation of it as a commentary on exclusion and its consequences. He shares his reading with a more politically aware friend, almost embarrassed by his own bookishness. But when they meet again years later, it turns out that his friend has taken Wilson’s essay very seriously. For in nineteenth-century Europe and its struggles, he discovered an environment much like his own. Although a new world of moral and material possibilities seemed to open up before the young men of his generation, now, as then, only a few would actually succeed in their strivings. Flaubert captured the mismatch that a modern youth experienced between “large, passionate, but imprecise longings” and the “slow, steady shrinking of horizons.” The European bildungsroman addressed what has become a worldwide situation in our time.

Mishra’s novel went on to diagnose the consequences of such a mismatch. After the students witness some rioting on campus, the friend explains with “a new vehemence” that the perpetrators were mainly “young men with nothing to do, nowhere to go, with no future, no prospects, nothing, nothing at all.” The bookish young man is clearly Mishra in another guise, down to their common birth year and education. His friend, who is more familiar, not simply with politics but also with criminality and violence, is also based on a real person; they met the year Mishra moved from Allahabad to Benares and fell in love himself with the literary criticism of Edmund Wilson. Mishra has not published another novel since. But in his admirable career writing on politics, he closely identifies with the lesson of his erstwhile friend (who later became a contract killer): If people are exposed to grandeur and then their horizons shrink, the results can prove dangerous.

While Mishra long ago recognized the uses of Western thought in understanding the causes of global rage, in his new book, Age of Anger, he turns to intellectual history to counter civilizational or theological explanations for that rage in its more recent forms. After September 11, 2001, a crew of specialists arose to designate Islam the cause of hatred and violence; their essential goal was to immunize our own way of life from blame and scrutiny. Such analysts could never anticipate how their own states and cultures gave rise to a broader discontent—including in Europe and the United States. After votes for Brexit and Donald Trump, it turns out it was not just “radicalized” Muslim youths who resented elites and resorted to violence as a means of revenge.

Instead, Mishra argues that the European past was a dry run for our global present. In the German and Russian populists and terrorists of the nineteenth century, Mishra finds avatars of the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, and the Muslim radical preacher Anwar al-Awlaki. In the “Frenchmen who bombed music halls, cafés, and the Paris stock exchange” in the 1880s and ’90s, he sees forerunners of today’s “English and Chinese nationalists, Somali pirates, human traffickers, and anonymous cyber-hackers.” Understanding political and economic inequality is vital to understanding these convulsions; but we also have to examine how the ideals we live with—of capitalism and liberalism—have long produced unbearable disillusionment. To grasp the fear and desire behind violent reaction, Mishra contends, we need not just Karl Marx and Thomas Piketty, but also analysts of the psyche and spirit.

Age of Anger traces today’s discontent back to the beginning of modernity, when Europe underwent commercial and, later, industrial revolutions, toppled its aristocratic elites and sometimes kings, and trumpeted freedom and equality, even as it redoubled the prestige of luxury and the lure of hierarchy. It was the start of the process of building a world of plenty and self-transformation, but also of distinction and envy. Philosophers of the eighteenth century diagnosed the likely outcome of this divide; the nineteenth century experienced that outcome, in furious, violent responses to it.

Mishra starts with a set piece on Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who offer us two opposing views of modernity and how to think about its shortcomings. Voltaire, the mainstream rationalist, embraced commerce and progress; he saw little daylight between the celebration of the one and the inevitability of the other. He endorsed individual freedom and pluralistic tolerance up to a point. Compared to the democratic mob, hereditary rulers—especially if well tutored by freethinkers like Voltaire himself—were less likely to become oppressive. He held a low opinion of Rousseau, the rebellious son of a Genevan watchmaker. Rousseau returned the compliment, writing to Voltaire in 1760, “I hate you.”

Rousseau, on the other hand, thought modernity was bringing about not progress but tragedy. Modern men and women learned to envy the magnificence of the winners and to define their ends in a triangular process of assessing what others valued first. In his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Rousseau depicted how enraging it is to subordinate oneself to the desires of others, in a state of exclusion from Voltaire’s opulent civilization. Because Rousseau had experienced the life of a social climber himself, he understood “the many uprooted men” who failed to “adapt themselves to a stable life in society,” and began to see that failure as the product of a larger “injustice against the human race.” Enslaved by manufactured desires, most Europeans experienced merely the frustration of never seeing them realized. Commercial modernity imprisoned the rich as much as the poor in a syndrome of “envy, fascination, revulsion, and rejection.”

It is Voltaire’s vision of modernity, however, that has been the more seductive one throughout much of history. His theory fueled the first age of globalization before World War I, and has gained currency again in the enthusiasm for markets that burgeoned after the end of the Cold War. “As Louis Vuitton opened in Borneo,” Mishra observes sarcastically, “it seemed only a matter of time before the love of luxury was followed by the rule of law, the enhanced use of critical reason, and the expansion of individual freedom.” But in part because the results benefit only a few, in part because modernity is a cage for everyone, Rousseau’s heirs await the moment to strike.

The question is: What are those left behind to do with their frustration? They can convert it, as Rousseau did, into insight into the limits of modernity, even for those who win the game. Or, sensing that there will be no chance of winning for all, especially as the competition goes global, they can wreak vengeance on the system.

Mishra sees an early example of such revenge in the German Romantics, whom he calls “the first angry young nationalists.” By the start of the nineteenth century, Germany—decades away from industrial modernity or even political unity—had failed to keep pace with the power and wealth that made Britain and France so opulent. Educated young Germans shared a sense of being belated, peripheral, and weak. They looked to France as “the home of the worldly, elegant, and sensuous philosopher, who spoke a language of unparalleled clarity and precision.” Yet when they arrived there, they perceived the same shallowness that Rousseau had seen before them. In 1769, the incisive philosopher J.G. Herder set out from the Baltic port of Riga to Paris, hoping to become gallicized. He left the next year, acutely disappointed, and convinced of the need to formulate a sturdy alternative to what he saw as hollow cosmopolitanism.

Building on Rousseau, German poets and philosophers such as Herder and Friedrich Schiller introduced a profound diagnosis of their own alienation. A feeling of being divided from the world, and even from one’s very self—as well as from one’s own work, as their follower Karl Marx added—was the worst thing about modern consciousness. Along with J.G. Fichte, Herder proposed a nationalist cure for this sense of estrangement. Herder extolled the popular genius of German Kultur, as well as the ineffability of particular cultures across the board. It was the opposite of the French idea of civilisation. Instead of seeking justification for their culture in progress and the promise of the future, Germans looked to the distant past to confirm their sense of national greatness, elevating folklore and myths to the pinnacle of high art. Whereas civilisation was centered on commerce, luxury, and urbanity, Kultur infused local ties and traditions with fervent spirituality, and idealized the Volk.

In the nineteenth century, such ideas drove German unification and national awakenings across Europe, and found their nadir in Adolf Hitler’s Germany in the twentieth century. Not only did nationalism give the world’s peasantries an outlet for their rage, but it now tempts those countries once at the apex of civilization toward populism. The Brexit vote and Trump’s unexpected win illustrate that when stagnation sets in at the center, anger can drive nationalist backlash. A nostalgia for “little England” takes revenge on cosmopolitan and diverse London, while calls to “make America great again” imply xenophobic and militaristic policies. Even Voltaire’s France is now a battleground in liberalism’s fight for survival against explosive nationalist resentment.

Mishra also lavishes attention on Russia, the first global hinterland where the Enlightenment’s liberatory wave crashed against the wall of a massive peasantry—sparking the invention of nihilism and terrorism. Since the Enlightenment, Russia’s ruling class had debated whether to westernize, and foreign kibitzers were divided over whether and how to extend civilization to Russia’s feudal society of aristocrats and serfs. (While Rousseau doubted it made sense to “tutor” Russia, Voltaire advised Empress Catherine the Great, and she bought his library after he died, hoping it would help.) But as the nineteenth century dragged on, autocratic rule did not bring forth progress fast enough to forestall its critics.

When you start so far behind, the very attempt to catch up breeds self-hatred. Your “conscience murmurs,” Fyodor Dostoevsky lamented, that you are “a hollow man,” condemned in advance to a “state of insatiable, bilious malice.” But whereas Dostoevsky only wrote about this discontent, other Russians took the route of terroristic deeds. The activist and thinker Mikhail Bakunin argued for the need to bring the system down in one swift stroke; he believed that “heroic acts” could “transform the world from an authoritarian cage into an arcadia of human freedom.” Battling against Marx for intellectual leadership of Europe’s working classes, Bakunin spawned a countercultural tradition of “lethal individualism,” whereby vivid destruction, instead of patient creation, would serve to define a self. His fellow critics of capitalism and empire were transnational. They bombed cities and assassinated political leaders across the Atlantic, inaugurating “the first phase of global jihad,” and anticipating the long-distance networks of lone wolves and terrorist cells of today.

“Large parts of Asia and Africa,” Mishra concludes, “are now plunging deeper” into their own “fateful experience of that modernity.” They are told they live on a flat earth, but find it impossible to claw their way forward on what feels like a vertical cliff of hierarchy. Westernization destroyed existing beliefs and institutions in these countries, promoting instead a culture of individual freedoms and rights. But, as Mishra points out, “Most newly created ‘individuals’ toil within poorly imagined social and political communities and/or states with weakening sovereignty,” narrowing the opportunities for personal flourishing. Western modernity opens up fault lines that “run through human souls as well as nations and societies undergoing massive change.” Out of the gap between expected liberation and experienced limits, fury boils.

A self-proclaimed history of the present, Age of Anger also feels like a blast from the past. In its literacy and literariness, it has the feel of Edmund Wilson’s extraordinary dramas of modern ideas—books like To the Finland Station—but with a different endpoint and a more global canvas. Mishra reads like a brilliant autodidact, putting to shame the many students who dutifully did the reading for their classes but missed the incandescent fire and penetrating insight in canonical texts. Yet his narrative of the outcasts of modernity has been told before, at different times and with different emphases, to explain earlier episodes of revolt and revolution: He is not the first to locate the origins of fascism in nineteenth-century German malcontents, and it was once popular to tag Rousseau for paving the way for communism and the student movement.

Nor is Mishra ready to offer solutions. Though he looks at the bleak record of commercial modernity in propagating itself across the world and marks its self-defeating expansion, he holds out no defined alternative. It is unclear whether Mishra feels the chief flaw lies in modernity’s failures—its false promise to liberate everyone—or in its successes, and the devastation that has accompanied them.

Of course, true freedom and equality beckon, which is why Mishra shows an occasional soft spot for lone wolves—including Timothy McVeigh—who hope a spectacular blow will shatter the glass. But ultimately, he does not hold up such anarchists as models. Indeed, even though they unceremoniously dismiss the “gaudy cult of progress,” it seems to Mishra nonetheless that “the men trying to radicalize the liberal principle of freedom and autonomy, of individual power and agency, seem more rootless and desperate than before.” In a world that can no longer count on progress, and that fears its consequences for the planet, Mishra praises Pope Francis’s exemplary moral stances on behalf of the environment and the poor—if only because no one else is offering hope. Yet he also acknowledges there is no going back to a premodern metaphysics or economy, when ambition has come to seem everyone’s birthright, first in Europe, later everywhere.

If intellectual history matters in this parlous situation, then getting Rousseau right does, too. Interpreting him, as Mishra does, as nostalgic for ancient liberty or protective of interior freedom in the face of the modern catastrophe, will ultimately not work. After all, Rousseau also rejected the viability of reviving the Sparta he sometimes idealized. For that reason, he thought carefully about how to bring about free communities of equals in our economic and political circumstances.

And he also wrote The Social Contract, a text Mishra barely addresses. After reading The Social Contract’s commitment to modern freedom and equality, a fellow Enlightenment thinker, Immanuel Kant, early saw that Rousseau’s main impulses between a lamentation for modernity and an emancipatory program for it have to be reconciled at all costs. There is no way to sever Rousseau’s critique of painful exclusion and “glittering misery”—now, as Mishra shows, applicable across the world and into its smallest byways—from a political attempt to answer it.

“Rousseau,” Kant remarked, “was not far wrong in preferring the state of savages—so long, that is, as the last stage to which the human race must climb is not attained.” Starting from his remote corner in the Benares library reading Edmund Wilson, no one has discerned better than Mishra just how far we still are from the top.

Original Article

Source: newrepublic.com/

Author: Samuel Moyn

No comments:

Post a Comment