The Brexit charge is that the European Union has become an overbearing political project threatening British sovereignty and values. Britain, so the story runs, is an exceptional country with an exceptional history, exceptional institutions and an exceptional destiny. For Europeans inured to political instability and bloodshed, supranational institutions are needed to keep the peace. These chosen British lands have no such need. The Brexit vote was a protest vote against an order that had created insupportable lives for too many British citizens, intensified by fears over immigration, but it was underpinned by this cultural narrative of Britain’s uniqueness.

Like all caricatures, this story contains enough truth to be plausible. As the dominant part of an island to the west of the continent, England after 1066 was able to develop parliamentary government, religious toleration and common law without the periodic invasions that beset other parts of mainland Europe. It was not occupied by Napoleon or Hitler or ravaged for decades by territorial-cum-religious war. It was first into the Industrial Revolution and built the most extensive of the European empires on the basis of maritime prowess as an island nation. It was on the winning side in the 20th century’s two world wars. English, once spoken only in the Thames valley, became the world language.

But there are limits to this account. It greatly overstates the uniqueness of English history, our differences with Europe and our differences with the other nations of the British Isles.

We have never been truly divorced from our continent. How could it be otherwise? England’s violent record in Ireland, Scotland and Wales should disabuse anyone who thinks our history is distinctively peaceful – and our record in empire-building was of a piece. All the currents that have shaped us – Roman, Saxon, Danish and Norman occupations, the Renaissance, the rise of Protestantism, the gains of overseas expansion, the concept of the nation-state, universal suffrage and the welfare state, industrialisation, the brutalities of early capitalism and the emergence of socialism – have shaped the rest of Europe, too. The development has been symbiotic.

Thus, Magna Carta was part of a family of European settlements that fettered monarchical feudal rights across Europe. England’s break with Rome under Henry VIII prefigured the cataclysm that overcame the Holy Roman Empire; England was part of the European state system established by the 1648 peace of Westphalia.

Sometimes, as with industrialisation, Britain was ahead of the pack, although we soon lost the advantage to Germany. Sometimes, as with votes for all women over 21 in 1928 or laying the foundations of a welfare state before the First World War, we were well behind Scandinavia and even ex-colonies Australia and New Zealand. On the welfare state, we took our cue from Bismarck. The Enlightenment was a pan-European movement. Indeed, there is a powerful argument for viewing the British Industrial Revolution as a European event, given how many of the key inventions had origins in European thinking and in immigrants, many of them refugees compelled to seek better lives here.

The truth is that Britain has been integrating immigrants and sharing sovereignty for centuries. As urban centres grew and trade and cultural networks flourished, supported by revolutionary advances in technology from the three-masted sailing ship to the printing press to electrification to containerisation, these connections have woven Britain, Europe and the rest of the world closer together.

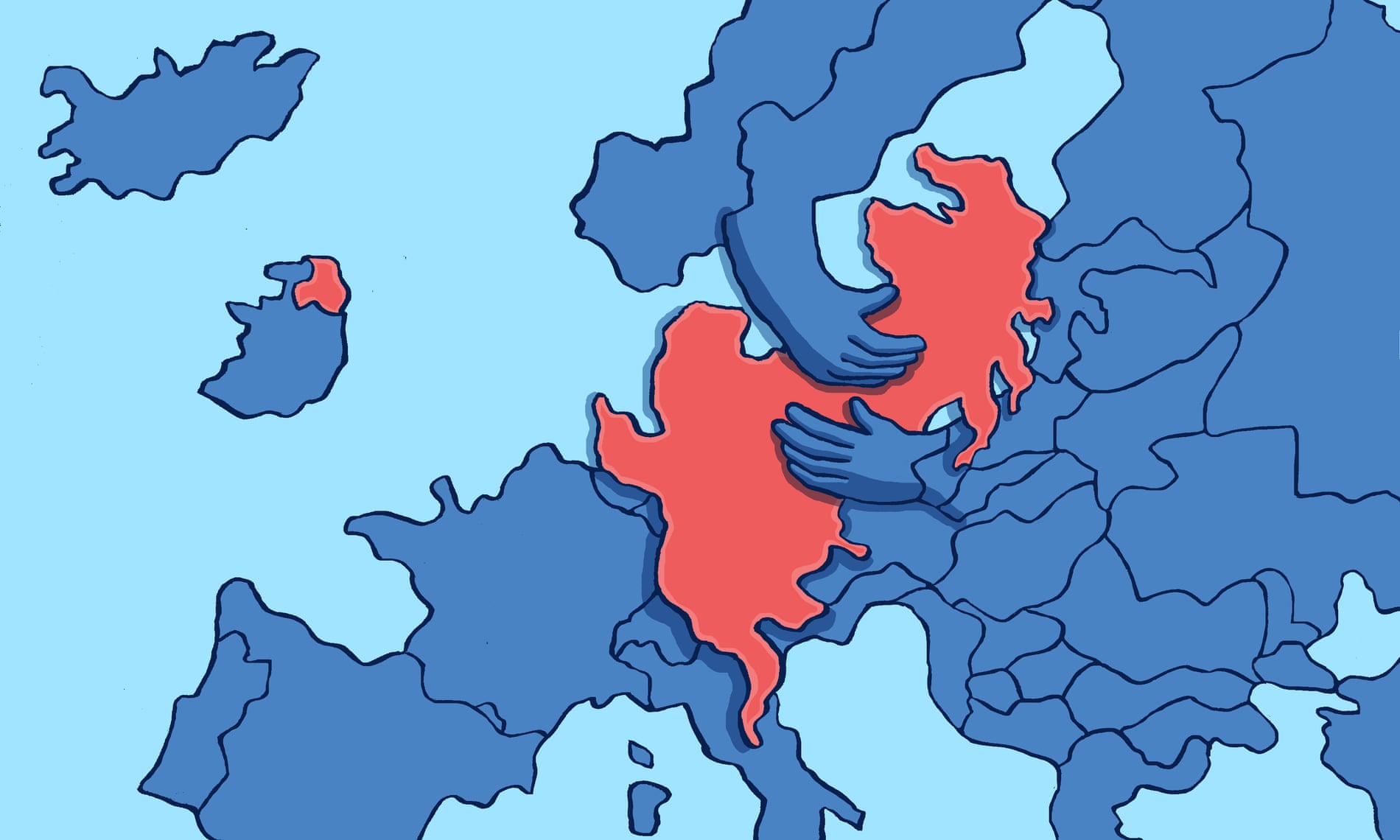

This interconnectedness has made cooperation more, not less, essential over time. Since 1834, Britain has signed more than 13,000 treaties and international conventions – a red-tape mountain – virtually all of which have diluted our notional sovereignty while advancing our national interest. The EU continues this process. The EU buildings that Boris Johnson sees ominously “looming over cobbled Brussels streets” are not representatives of some terrifying “other”: none of the EU’s members has ambitions – whether public or cryptic – to submerge their nation into a federal superstate. There is no European army massing in Calais. The EU’s buildings represent an often ticklish interdependence in which we Europeans devise solutions to shared problems – from environment to trade, from security to terrorism – that we could not have applied on our own. It is a construct for the future. Brexit is a step back to an imagined past that never existed.

European Britain

Even as England became a separate state from parts of the European mainland in the 16th century, engagement remained intense. Elizabeth I spoke six European languages and regarded herself as a “prince of Europe”. Resisting marriage advances by French and German princes lest they cramp her options, she was as deeply engaged as any of them in the culture and politics of the European Reformation and Counter-Reformation.

Shakespeare’s Jaques (As You Like It) said that “all the world’s a stage”, but Europe was Shakespeare’s actual stage – all of it, together with its history: Venice, Verona, Sicily, Denmark, Athens, Rome, Paris, Vienna, Milan, Naples, Mantua, Cyprus, Bohemia, Illyria (Croatia), Navarre (Spain), Troy and Antioch (Turkey). And most exotic of all, the unnamed, heavenly Mediterranean isle of The Tempest, of which Caliban tells the shipwrecked Stephano: “Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises, Sounds, and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.” Political unions between England and mainland Europe continued long after Mary I, married to Philip II of Spain, was evicted from Calais in 1558. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought William of Orange (the Netherlands) to the English throne. After the death of the childless Queen Anne in 1714, the throne passed to her cousin George, Prince of Hanover, an Anglo-German union of crowns that continued until Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837. Victoria promptly united with Saxe-Coburg in her marriage to Prince Albert. Victoria’s great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II – Elizabeth I of Scotland, which “the Faerie Queene” did not rule – is cousin to the kings or queens of Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands. Her husband, Prince Philip, is a prince of Greece and Denmark and son of a German princess.

So the monarchy is the most European of English institutions, just as it is the most Scottish and Welsh. It is nonetheless ambiguous. For as well as her European relationships, the Queen continues to be head of state of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. She is also head of the Commonwealth, a club of 53 mostly ex-colonies which still have strong cultural, educational, sporting and economic links to Britain despite the relative decline of the mother country. If those bonds are weakening, it is not because of the EU – it is because of Britain’s fading economic and political relevance.

A similar story of tension between England Alone and European Britain is told across England’s intellectual, political, diplomatic, religious and cultural life. David Hockney was strongly influenced by Picasso, David Bowie’s talent flowered in Berlin, George Orwell wrote in Paris and Catalonia. Isaac Newton was far more internationally famous than Shakespeare in his day, because he wrote for a European audience in Latin. Only since the late 18th century have English language and culture held significant sway in mainland Europe. Even then, it took 150 years of revolution, turmoil and occupation for London to replace Paris as the capital of Europe. By the late 18th century, Britain’s leading scholars were writing in English, but no less engaged in Europe for their ideas and influence.

Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, started writing The Wealth of Nations in Toulouse, while touring the continent as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch. He met Voltaire in Geneva and David Hume in Paris, where his fellow Scot was secretary of the British embassy. Hume introduced him to all the great writers of the French Enlightenment. Smith even intended – his sudden death intervened – to dedicate his great book on the “invisible hand” of the free market to François Quesnay, a French economist as well as physician to Louis XV.

The Industrial Revolution arrived in Britain not just because of British genius, or because we had abundant coal and running soft water, but due to the interplay with the European Enlightenment. The leading economic historian Joel Mokyr argues that the quest for knowledge that defined the Industrial Revolution – led by great inventors such as James Watt, Richard Arkwright and Josiah Wedgwood – was inspired by an Enlightenment seeking to open up the world to the force of reason.

Inventors and thinkers alike converged on Britain, whose political institutions, tolerance and openness made it a European hub. As Hume wrote: “Notwithstanding the advanced state of our manufactures we daily adopt, in art, the inventions and improvements of our neighbours.” Whether it was Leblanc’s soda-making system, Jacquard’s loom or De Girard’s wet-spinning process, the British proved adept at absorbing European ideas from whatever source to reinforce their technological prowess and leadership.

The Industrial Revolution transformed not only British but also European societies and polities. Managing the convulsions and uncertainties associated with industrialisation led to common responses: while the details differed, social unrest allied to Enlightenment views of individualisation and human rights was a catalyst for democratisation, which opened the door for redistribution and the extension of social and educational rights to the masses. William Beveridge, godfather of the NHS and postwar welfare state, studied extensively the systems of compulsory social insurance for pensions and sickness that Bismarck had introduced into Germany in the 1880s.

Beveridge wrote about them as a journalist at the Tory Morning Post. This work caught the eye of a 33-year-old Winston Churchill, who in 1908 brought Beveridge into the Board of Trade. A year later, Beveridge’s ideas were central to David Lloyd George’s famous People’s Budget of 1909. It was the rise of a new pan-European generation. England’s self-styled Brexit historian Robert Tombs argued after the 2016 referendum that joining the European Union was “an immense historic error” born of “exaggerated fears of national decline and marginalisation [and] a vain attempt to be at the heart of Europe”. But his The English and their History, published two years before the Brexit vote, when it looked as if it would go the other way, makes no such claim for English exceptionalism. Its rich tapestry of England’s intense engagement and rapprochement with its neighbours more readily sustains an argument for British leadership in Europe than it justifies disengagement. “England’s successive incorporation into Great Britain, the United Kingdom, the empire, the European Community and a multicultural global society added ever more layers of identity,” he declares. “The past it seems is not dead – it is not even past.”

Churchill’s ‘three great circles’

The greatest Briton, Winston Churchill, exemplifies the English European who never turned his back on the European mainland. Churchill had an American mother and an imperial destiny from his boyhood at Harrow and Sandhurst, as a young officer on India’s North-West Frontier and then a reporter in the South African war. Yet he was equally proud of being a descendant and biographer of the Duke of Marlborough, victor of Blenheim in league with Germans against the hegemonic Roi Soleil, Louis XIV.

And therein lies an episode of significance for the history of Europe. While visiting Marlborough’s battlefields in Bavaria in 1932, Churchill nearly met Hitler. The Nazi leader, about to take power, had been due to meet Churchill at his hotel in Munich but – in a moment rich with symbolism – he cancelled at the last minute because Churchill had berated the Nazi leader’s press secretary the night before about antisemitism.

“Why is your chief so violent about the Jews? What is the sense of being against a man simply because of his birth? How can any man help how he is born?” Churchill recalled saying. And the upshot: “He must have repeated this to Hitler, because about noon the next day he came round with rather a serious air and said that the appointment could not take place.”

Maybe the most fateful non-meeting in history.

Churchill never saw empire as a reason for British isolation from Europe. Faced by the ultimate crisis, he spurned Chamberlain’s isolationist view of Czechoslovakia as “a far-away country”. Instead, he stood up to Hitler, offered the French an “indissoluble union” to keep them in the war as Hitler’s armies advanced on Paris in June 1940, refused to contemplate the armistice urged on him by his foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, after the fall of France and pursued to the end a war to liberate Europe from “the pestilence of Nazi tyranny”. But note for devotees of Darkest Hour and Dunkirk: Britain was never “alone” and could not have triumphed had it been so. Even in its darkest hour Britain could call on its then vast empire and, within 18 months, on the Americans, too. It also had a powerful defence industry incorporating Europe’s largest and most sophisticated aviation industry, built up in the 1930s by methods that rejected laissez-faire. Britain could and did outproduce Germany.

Today’s pro- and anti-Europeans quote different Churchill postwar speeches. “We must build a kind of United States of Europe” is the classic federalist quote from his 1946 Zurich speech. “We are with them, but not of them” is the classic anti-integration quote when he was prime minister for the second time in 1953. However, swapping quotes out of context is no substitute for understanding Churchill’s thinking, which was consistently in favour of strong European engagement.

For Churchill, as for Attlee, his internationalist Labour counterpart, the issue of the 1940s was to combine European engagement, imperial power and global partnership with the United States.

He set this out at length in his “three great circles” speech at Llandudno in 1948. “I almost wish I had a blackboard, I would make a picture for you,” he told Tory activists. “The first circle for us is naturally the British Commonwealth and empire. Then there is the English-speaking world in which we, Canada, and the other British Dominions and the United States play so important a part. And finally there is United Europe. These three majestic circles are coexistent and if they are linked together there is no force or combination which could overthrow them or even challenge them… We stand… here in this Island at the centre of the seaways and perhaps of the airways also, we have the opportunity of joining them all together. [In doing so] we hold the key to opening a safe and happy future to humanity, and will gain for ourselves gratitude and fame.”

Churchill’s approach was unambiguously to maximise British influence in all three circles, not to disengage. Seventy years after Llandudno, Britain has only one circle left intact – “United Europe” – and it is implausible that Churchill would have favoured disengagement from that one. On the contrary, he would have seen British leadership of the EU as all the more imperative because it is now our principal circle of influence. He would have been equally resolute in support of Nato, being the legacy of his wartime alliance with the United States that still secures British security and influence, but it is inconceivable that he would have regarded this as a substitute for the EU.

The key point about Churchill’s 1953 “with them but not of them” remark is that it was in the context of France and Germany debating the establishment of an integrated “defence community” separate from the US, a stillborn precursor of the economic community that they went on to found in 1957.

Churchill was not in principle against close military engagement with France and Germany, but in the context of the early 1950s he did not want to weaken the Anglo-American bedrock of Nato by supporting a speculative bid for a European army.

In the event, the French parliament rejected the defence community, for reasons similar to Churchill’s. However, on economic cooperation Churchill was consistently positive. “We are prepared to consider, and if convinced to accept, the abrogation of national sovereignty, provided that we are satisfied with the conditions and the safeguards,” he said of the Schuman Plan in 1950. A year later, he was more explicit in disowning isolationism: “There are disadvantages and even dangers to us in standing aloof.” And after he left No 10, he supported Macmillan’s application to join the EU, having privately opposed Eden’s ill-fated Suez expedition in 1956.

“In defeat, defiance” was another Churchill maxim. He never gave up the struggle to change public opinion and the Conservative party to his way of thinking, even when threatened with deselection as Tory MP for Woodford in Essex, now Iain Duncan Smith’s constituency, for opposing Chamberlain on his Munich agreement with Hitler to dismember Czechoslovakia.

Where the weather comes from

The Brexiter argument that Britain has outgrown the old continent has a long pedigree. Global Britain, descended from the “blue water” tradition, assumes a future in which Britain escapes European geography, European engagement and European immigration. Out in that blue yonder, there are no risks, no power imbalances and no limitations on sovereignty.

This Global Britain, ludicrously branded “Empire 2.0” by some Brexiters, is a piece of flimsy nonsense, particularly as our former empire is entirely self-governing, the Commonwealth is a club with no clout and there are no uncolonised continents besides the Antarctic ripe for exploitation. The reality is that British strategic thinking has always been – has always had to be – at least as European as global. To argue, as Brexiters do, that we are not leaving Europe but rather the EU is elemental fatuity. The institutions of the EU are today’s Europe: they are where Europe’s states cut their deals, organise the economics, politics and security of our continent, hammer out joint foreign policy and are through which the shared rules that keep our borders open to the friction-free movement of goods, services, money and people are sustained. And all is congruent with democracy, the rule of law and accountability. They are a magnificent achievement. To argue differently is to traduce the evidence of our eyes – and a betrayal of our interests as a European power.

For European balance-of-power politics, so advancing our national interest, has been a central theme of our history. We resisted the emergence of Spain, then France and then Germany as would-be dominators of our continent by building countervailing alliances. We helped defend Europe against outside predators – the Turks in their time, and in the last century the Soviet Union. The crusades, misguided as they were, were in their day quintessentially European. Britain built its overseas possessions in part to secure a better counterweight in Europe.

As Churchill said, Europe is “where the weather comes from”. It is a Brexit fallacy that being out of the EU means being spared what happens in the EU and the eurozone. Britain has an existential interest in what happens in Europe, as it always has. There is no hiding place in the Atlantic.

Today, risks are mounting, democracy is under threat worldwide, even in recently confident and progressive western Europe and North America. Putin’s Russia is behaving like the fascist regimes of the 1930s, backed by sophisticated raids from online troll factories. Citizens – and ominously younger voters in some European countries – are more and more willing to tolerate the subversion of democratic norms and express support for authoritarian alternatives.

Oleg Kalugin, former major general of the Committee for State Security (the KGB), has described sowing dissent as “the heart and soul” of the Putin state: not intelligence collection, but subversion – active measures to weaken the west, to drive wedges in the western community alliances of all sorts, particularly Nato, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people of Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs. To make America more vulnerable to the anger and distrust of other peoples.

In Brexit-voting Weymouth, Captain Malcolm Shakesby of Ukip is unruffled by Putin or European populism. He inhabits the cartoon world of British exceptionalism, and his main concern today is Mrs May’s “sellout” of the referendum result. Brexit, uncorrupted, will be a success. “It will work because the British people are resilient,” he says. Then, in full Dunkirk mode: “In the Second World War, when we were down, we managed to pull through. The French couldn’t hack it, the Netherlands couldn’t hack it, the Belgians couldn’t hack it. We would have done what Churchill said, fight them on the beaches. That’s what nobody else ever does.” Of course Churchill did not actually do that – fighting on the beaches – and his whole statesmanship was to ensure that we did not have to, either.

The MP for Shakesby’s South Dorset constituency is a Conservative who won the seat from New Labour in 2010. He, too, is a captain, one Captain Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, educated at Harrow, then Sandhurst and the Coldstream Guards, grandson of Admiral Sir Reginald Drax and great-grandson of Lord Dunsany, second oldest title in the peerage of Ireland. Drax is quintessential governing class. At least six of his ancestors since the 17th century were MPs for Dorset or Gloucestershire. His home: the ancestral seat, Charborough House, Grade I listed, deer park and 7,000 acres. The grounds are open to the public twice a year, when the villagers of Sturminster Marshall are admitted to sell tea and cakes.

Drax’s view on Brexit? “Resignation is the only honourable path” for MPs who won’t accept it. Drax is tribute to the Faragist takeover of the Tory party. It is a party now indifferent to Britain’s place in Europe and blind to the vital need for full engagement with our continent. Mouthing Churchillian rhetoric, while disowning the statecraft that underpinned it, is the lion without the roar.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com

Author: Will Hutton and Andrew Adonis

Like all caricatures, this story contains enough truth to be plausible. As the dominant part of an island to the west of the continent, England after 1066 was able to develop parliamentary government, religious toleration and common law without the periodic invasions that beset other parts of mainland Europe. It was not occupied by Napoleon or Hitler or ravaged for decades by territorial-cum-religious war. It was first into the Industrial Revolution and built the most extensive of the European empires on the basis of maritime prowess as an island nation. It was on the winning side in the 20th century’s two world wars. English, once spoken only in the Thames valley, became the world language.

But there are limits to this account. It greatly overstates the uniqueness of English history, our differences with Europe and our differences with the other nations of the British Isles.

We have never been truly divorced from our continent. How could it be otherwise? England’s violent record in Ireland, Scotland and Wales should disabuse anyone who thinks our history is distinctively peaceful – and our record in empire-building was of a piece. All the currents that have shaped us – Roman, Saxon, Danish and Norman occupations, the Renaissance, the rise of Protestantism, the gains of overseas expansion, the concept of the nation-state, universal suffrage and the welfare state, industrialisation, the brutalities of early capitalism and the emergence of socialism – have shaped the rest of Europe, too. The development has been symbiotic.

Thus, Magna Carta was part of a family of European settlements that fettered monarchical feudal rights across Europe. England’s break with Rome under Henry VIII prefigured the cataclysm that overcame the Holy Roman Empire; England was part of the European state system established by the 1648 peace of Westphalia.

Sometimes, as with industrialisation, Britain was ahead of the pack, although we soon lost the advantage to Germany. Sometimes, as with votes for all women over 21 in 1928 or laying the foundations of a welfare state before the First World War, we were well behind Scandinavia and even ex-colonies Australia and New Zealand. On the welfare state, we took our cue from Bismarck. The Enlightenment was a pan-European movement. Indeed, there is a powerful argument for viewing the British Industrial Revolution as a European event, given how many of the key inventions had origins in European thinking and in immigrants, many of them refugees compelled to seek better lives here.

The truth is that Britain has been integrating immigrants and sharing sovereignty for centuries. As urban centres grew and trade and cultural networks flourished, supported by revolutionary advances in technology from the three-masted sailing ship to the printing press to electrification to containerisation, these connections have woven Britain, Europe and the rest of the world closer together.

This interconnectedness has made cooperation more, not less, essential over time. Since 1834, Britain has signed more than 13,000 treaties and international conventions – a red-tape mountain – virtually all of which have diluted our notional sovereignty while advancing our national interest. The EU continues this process. The EU buildings that Boris Johnson sees ominously “looming over cobbled Brussels streets” are not representatives of some terrifying “other”: none of the EU’s members has ambitions – whether public or cryptic – to submerge their nation into a federal superstate. There is no European army massing in Calais. The EU’s buildings represent an often ticklish interdependence in which we Europeans devise solutions to shared problems – from environment to trade, from security to terrorism – that we could not have applied on our own. It is a construct for the future. Brexit is a step back to an imagined past that never existed.

European Britain

Even as England became a separate state from parts of the European mainland in the 16th century, engagement remained intense. Elizabeth I spoke six European languages and regarded herself as a “prince of Europe”. Resisting marriage advances by French and German princes lest they cramp her options, she was as deeply engaged as any of them in the culture and politics of the European Reformation and Counter-Reformation.

Shakespeare’s Jaques (As You Like It) said that “all the world’s a stage”, but Europe was Shakespeare’s actual stage – all of it, together with its history: Venice, Verona, Sicily, Denmark, Athens, Rome, Paris, Vienna, Milan, Naples, Mantua, Cyprus, Bohemia, Illyria (Croatia), Navarre (Spain), Troy and Antioch (Turkey). And most exotic of all, the unnamed, heavenly Mediterranean isle of The Tempest, of which Caliban tells the shipwrecked Stephano: “Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises, Sounds, and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.” Political unions between England and mainland Europe continued long after Mary I, married to Philip II of Spain, was evicted from Calais in 1558. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought William of Orange (the Netherlands) to the English throne. After the death of the childless Queen Anne in 1714, the throne passed to her cousin George, Prince of Hanover, an Anglo-German union of crowns that continued until Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837. Victoria promptly united with Saxe-Coburg in her marriage to Prince Albert. Victoria’s great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II – Elizabeth I of Scotland, which “the Faerie Queene” did not rule – is cousin to the kings or queens of Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands. Her husband, Prince Philip, is a prince of Greece and Denmark and son of a German princess.

So the monarchy is the most European of English institutions, just as it is the most Scottish and Welsh. It is nonetheless ambiguous. For as well as her European relationships, the Queen continues to be head of state of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. She is also head of the Commonwealth, a club of 53 mostly ex-colonies which still have strong cultural, educational, sporting and economic links to Britain despite the relative decline of the mother country. If those bonds are weakening, it is not because of the EU – it is because of Britain’s fading economic and political relevance.

A similar story of tension between England Alone and European Britain is told across England’s intellectual, political, diplomatic, religious and cultural life. David Hockney was strongly influenced by Picasso, David Bowie’s talent flowered in Berlin, George Orwell wrote in Paris and Catalonia. Isaac Newton was far more internationally famous than Shakespeare in his day, because he wrote for a European audience in Latin. Only since the late 18th century have English language and culture held significant sway in mainland Europe. Even then, it took 150 years of revolution, turmoil and occupation for London to replace Paris as the capital of Europe. By the late 18th century, Britain’s leading scholars were writing in English, but no less engaged in Europe for their ideas and influence.

Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, started writing The Wealth of Nations in Toulouse, while touring the continent as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch. He met Voltaire in Geneva and David Hume in Paris, where his fellow Scot was secretary of the British embassy. Hume introduced him to all the great writers of the French Enlightenment. Smith even intended – his sudden death intervened – to dedicate his great book on the “invisible hand” of the free market to François Quesnay, a French economist as well as physician to Louis XV.

The Industrial Revolution arrived in Britain not just because of British genius, or because we had abundant coal and running soft water, but due to the interplay with the European Enlightenment. The leading economic historian Joel Mokyr argues that the quest for knowledge that defined the Industrial Revolution – led by great inventors such as James Watt, Richard Arkwright and Josiah Wedgwood – was inspired by an Enlightenment seeking to open up the world to the force of reason.

Inventors and thinkers alike converged on Britain, whose political institutions, tolerance and openness made it a European hub. As Hume wrote: “Notwithstanding the advanced state of our manufactures we daily adopt, in art, the inventions and improvements of our neighbours.” Whether it was Leblanc’s soda-making system, Jacquard’s loom or De Girard’s wet-spinning process, the British proved adept at absorbing European ideas from whatever source to reinforce their technological prowess and leadership.

The Industrial Revolution transformed not only British but also European societies and polities. Managing the convulsions and uncertainties associated with industrialisation led to common responses: while the details differed, social unrest allied to Enlightenment views of individualisation and human rights was a catalyst for democratisation, which opened the door for redistribution and the extension of social and educational rights to the masses. William Beveridge, godfather of the NHS and postwar welfare state, studied extensively the systems of compulsory social insurance for pensions and sickness that Bismarck had introduced into Germany in the 1880s.

Beveridge wrote about them as a journalist at the Tory Morning Post. This work caught the eye of a 33-year-old Winston Churchill, who in 1908 brought Beveridge into the Board of Trade. A year later, Beveridge’s ideas were central to David Lloyd George’s famous People’s Budget of 1909. It was the rise of a new pan-European generation. England’s self-styled Brexit historian Robert Tombs argued after the 2016 referendum that joining the European Union was “an immense historic error” born of “exaggerated fears of national decline and marginalisation [and] a vain attempt to be at the heart of Europe”. But his The English and their History, published two years before the Brexit vote, when it looked as if it would go the other way, makes no such claim for English exceptionalism. Its rich tapestry of England’s intense engagement and rapprochement with its neighbours more readily sustains an argument for British leadership in Europe than it justifies disengagement. “England’s successive incorporation into Great Britain, the United Kingdom, the empire, the European Community and a multicultural global society added ever more layers of identity,” he declares. “The past it seems is not dead – it is not even past.”

Churchill’s ‘three great circles’

The greatest Briton, Winston Churchill, exemplifies the English European who never turned his back on the European mainland. Churchill had an American mother and an imperial destiny from his boyhood at Harrow and Sandhurst, as a young officer on India’s North-West Frontier and then a reporter in the South African war. Yet he was equally proud of being a descendant and biographer of the Duke of Marlborough, victor of Blenheim in league with Germans against the hegemonic Roi Soleil, Louis XIV.

And therein lies an episode of significance for the history of Europe. While visiting Marlborough’s battlefields in Bavaria in 1932, Churchill nearly met Hitler. The Nazi leader, about to take power, had been due to meet Churchill at his hotel in Munich but – in a moment rich with symbolism – he cancelled at the last minute because Churchill had berated the Nazi leader’s press secretary the night before about antisemitism.

“Why is your chief so violent about the Jews? What is the sense of being against a man simply because of his birth? How can any man help how he is born?” Churchill recalled saying. And the upshot: “He must have repeated this to Hitler, because about noon the next day he came round with rather a serious air and said that the appointment could not take place.”

Maybe the most fateful non-meeting in history.

Churchill never saw empire as a reason for British isolation from Europe. Faced by the ultimate crisis, he spurned Chamberlain’s isolationist view of Czechoslovakia as “a far-away country”. Instead, he stood up to Hitler, offered the French an “indissoluble union” to keep them in the war as Hitler’s armies advanced on Paris in June 1940, refused to contemplate the armistice urged on him by his foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, after the fall of France and pursued to the end a war to liberate Europe from “the pestilence of Nazi tyranny”. But note for devotees of Darkest Hour and Dunkirk: Britain was never “alone” and could not have triumphed had it been so. Even in its darkest hour Britain could call on its then vast empire and, within 18 months, on the Americans, too. It also had a powerful defence industry incorporating Europe’s largest and most sophisticated aviation industry, built up in the 1930s by methods that rejected laissez-faire. Britain could and did outproduce Germany.

Today’s pro- and anti-Europeans quote different Churchill postwar speeches. “We must build a kind of United States of Europe” is the classic federalist quote from his 1946 Zurich speech. “We are with them, but not of them” is the classic anti-integration quote when he was prime minister for the second time in 1953. However, swapping quotes out of context is no substitute for understanding Churchill’s thinking, which was consistently in favour of strong European engagement.

For Churchill, as for Attlee, his internationalist Labour counterpart, the issue of the 1940s was to combine European engagement, imperial power and global partnership with the United States.

He set this out at length in his “three great circles” speech at Llandudno in 1948. “I almost wish I had a blackboard, I would make a picture for you,” he told Tory activists. “The first circle for us is naturally the British Commonwealth and empire. Then there is the English-speaking world in which we, Canada, and the other British Dominions and the United States play so important a part. And finally there is United Europe. These three majestic circles are coexistent and if they are linked together there is no force or combination which could overthrow them or even challenge them… We stand… here in this Island at the centre of the seaways and perhaps of the airways also, we have the opportunity of joining them all together. [In doing so] we hold the key to opening a safe and happy future to humanity, and will gain for ourselves gratitude and fame.”

Churchill’s approach was unambiguously to maximise British influence in all three circles, not to disengage. Seventy years after Llandudno, Britain has only one circle left intact – “United Europe” – and it is implausible that Churchill would have favoured disengagement from that one. On the contrary, he would have seen British leadership of the EU as all the more imperative because it is now our principal circle of influence. He would have been equally resolute in support of Nato, being the legacy of his wartime alliance with the United States that still secures British security and influence, but it is inconceivable that he would have regarded this as a substitute for the EU.

The key point about Churchill’s 1953 “with them but not of them” remark is that it was in the context of France and Germany debating the establishment of an integrated “defence community” separate from the US, a stillborn precursor of the economic community that they went on to found in 1957.

Churchill was not in principle against close military engagement with France and Germany, but in the context of the early 1950s he did not want to weaken the Anglo-American bedrock of Nato by supporting a speculative bid for a European army.

In the event, the French parliament rejected the defence community, for reasons similar to Churchill’s. However, on economic cooperation Churchill was consistently positive. “We are prepared to consider, and if convinced to accept, the abrogation of national sovereignty, provided that we are satisfied with the conditions and the safeguards,” he said of the Schuman Plan in 1950. A year later, he was more explicit in disowning isolationism: “There are disadvantages and even dangers to us in standing aloof.” And after he left No 10, he supported Macmillan’s application to join the EU, having privately opposed Eden’s ill-fated Suez expedition in 1956.

“In defeat, defiance” was another Churchill maxim. He never gave up the struggle to change public opinion and the Conservative party to his way of thinking, even when threatened with deselection as Tory MP for Woodford in Essex, now Iain Duncan Smith’s constituency, for opposing Chamberlain on his Munich agreement with Hitler to dismember Czechoslovakia.

Where the weather comes from

The Brexiter argument that Britain has outgrown the old continent has a long pedigree. Global Britain, descended from the “blue water” tradition, assumes a future in which Britain escapes European geography, European engagement and European immigration. Out in that blue yonder, there are no risks, no power imbalances and no limitations on sovereignty.

This Global Britain, ludicrously branded “Empire 2.0” by some Brexiters, is a piece of flimsy nonsense, particularly as our former empire is entirely self-governing, the Commonwealth is a club with no clout and there are no uncolonised continents besides the Antarctic ripe for exploitation. The reality is that British strategic thinking has always been – has always had to be – at least as European as global. To argue, as Brexiters do, that we are not leaving Europe but rather the EU is elemental fatuity. The institutions of the EU are today’s Europe: they are where Europe’s states cut their deals, organise the economics, politics and security of our continent, hammer out joint foreign policy and are through which the shared rules that keep our borders open to the friction-free movement of goods, services, money and people are sustained. And all is congruent with democracy, the rule of law and accountability. They are a magnificent achievement. To argue differently is to traduce the evidence of our eyes – and a betrayal of our interests as a European power.

For European balance-of-power politics, so advancing our national interest, has been a central theme of our history. We resisted the emergence of Spain, then France and then Germany as would-be dominators of our continent by building countervailing alliances. We helped defend Europe against outside predators – the Turks in their time, and in the last century the Soviet Union. The crusades, misguided as they were, were in their day quintessentially European. Britain built its overseas possessions in part to secure a better counterweight in Europe.

As Churchill said, Europe is “where the weather comes from”. It is a Brexit fallacy that being out of the EU means being spared what happens in the EU and the eurozone. Britain has an existential interest in what happens in Europe, as it always has. There is no hiding place in the Atlantic.

Today, risks are mounting, democracy is under threat worldwide, even in recently confident and progressive western Europe and North America. Putin’s Russia is behaving like the fascist regimes of the 1930s, backed by sophisticated raids from online troll factories. Citizens – and ominously younger voters in some European countries – are more and more willing to tolerate the subversion of democratic norms and express support for authoritarian alternatives.

Oleg Kalugin, former major general of the Committee for State Security (the KGB), has described sowing dissent as “the heart and soul” of the Putin state: not intelligence collection, but subversion – active measures to weaken the west, to drive wedges in the western community alliances of all sorts, particularly Nato, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people of Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs. To make America more vulnerable to the anger and distrust of other peoples.

In Brexit-voting Weymouth, Captain Malcolm Shakesby of Ukip is unruffled by Putin or European populism. He inhabits the cartoon world of British exceptionalism, and his main concern today is Mrs May’s “sellout” of the referendum result. Brexit, uncorrupted, will be a success. “It will work because the British people are resilient,” he says. Then, in full Dunkirk mode: “In the Second World War, when we were down, we managed to pull through. The French couldn’t hack it, the Netherlands couldn’t hack it, the Belgians couldn’t hack it. We would have done what Churchill said, fight them on the beaches. That’s what nobody else ever does.” Of course Churchill did not actually do that – fighting on the beaches – and his whole statesmanship was to ensure that we did not have to, either.

The MP for Shakesby’s South Dorset constituency is a Conservative who won the seat from New Labour in 2010. He, too, is a captain, one Captain Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, educated at Harrow, then Sandhurst and the Coldstream Guards, grandson of Admiral Sir Reginald Drax and great-grandson of Lord Dunsany, second oldest title in the peerage of Ireland. Drax is quintessential governing class. At least six of his ancestors since the 17th century were MPs for Dorset or Gloucestershire. His home: the ancestral seat, Charborough House, Grade I listed, deer park and 7,000 acres. The grounds are open to the public twice a year, when the villagers of Sturminster Marshall are admitted to sell tea and cakes.

Drax’s view on Brexit? “Resignation is the only honourable path” for MPs who won’t accept it. Drax is tribute to the Faragist takeover of the Tory party. It is a party now indifferent to Britain’s place in Europe and blind to the vital need for full engagement with our continent. Mouthing Churchillian rhetoric, while disowning the statecraft that underpinned it, is the lion without the roar.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com

Author: Will Hutton and Andrew Adonis

No comments:

Post a Comment