WASHINGTON — It might be time for another midnight ride by Paul Revere, this time warning "the creditors are coming."

Americans seem not to have awakened to the fast-looming debt crisis that could summon a new recession, imperil their stock market investments and shatter faith in the world's most powerful economy. Those are among the implications, both sudden and long-lasting, expected to unfold if the U.S. defaults on debt payments for the first time in history.

Facing an August deadline for raising the country's borrowing limit or setting loose the consequences, politicians and economists are plenty alarmed. The people? Apparently not so much.

They're divided on whether to raise the limit, according to an Associated Press-GfK poll that found 41 percent opposed to the idea and 38 percent in favor.

People aren't exactly blase. A narrow majority in the poll expects an economic crisis to ensue if the U.S., maxed out on its borrowing capacity, starts missing interest payments to creditors. But even among that group, 37 percent say no dice to raising the limit.

In Washington's humid air, talk of a financial apocalypse is thick.

There are warnings of "credit markets in a state of panic," as the House Budget Committee chairman, Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., put it, causing a sudden drop-off in the country's ability to borrow and pushing the government off a "credit cliff."

He was characterizing a report by the government's nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office that warns of a "sudden fiscal crisis" in which investors might abandon U.S. bonds and force the government to pay steep interest rates and impose spending cuts and tax increases far more Draconian than if default were avoided.

The dire warnings appear to be falling on unconvinced ears, at least so far.

Call it doomsday fatigue.

In recent times, Americans heard that things were going to go haywire with the turn of the millennium, and they didn't. They were primed for post-Sept. 11 terrorist plots that did not unfold.

They've seen Congress, a lumbering body that gets fleet of foot at the last minute, come to the brink time after time, only to pull something out of its hat. Recently, a partial government shutdown was averted in that manner.

To Robin Knight, 50-year-old teacher from Gilbert, Ariz., who's trying to stay informed on the debt crisis, Washington's tendency to cry wolf and stage histrionics on issues of the day isn't helping.

"It should be very easy to understand," she said, "but I think there are so many skewed views and time given to people screaming that it can be hard to follow."

As during the lead-up to the government shutdown that didn't happen, tortured negotiations are under way.

Republican leaders are insisting on huge spending cuts as a condition for raising the debt limit. This position finds solid support from Republicans in the poll and backing from a plurality of independents.

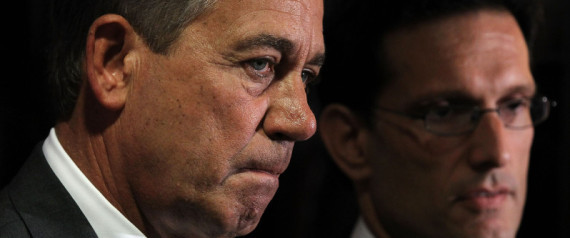

President Barack Obama is pushing for increased tax revenue to be part of the deal, and that insistence led House Republican leader Eric Cantor of Virginia to walk out of the negotiations this past week.

About half of Democrats in the poll said the debt limit should be raised regardless of whether it's paired with a deal to cut spending.

The survey found no significant differences by education, age, income, or even by party, in perceptions of whether a crisis is likely if the limit is not increased. There was widespread dissatisfaction with how Obama is dealing with the deficit – a new high of 63 percent disapproval on that subject – and an even harsher judgment of how both parties in Congress are doing on the issue.

Full Article

Source: Huffington

Americans seem not to have awakened to the fast-looming debt crisis that could summon a new recession, imperil their stock market investments and shatter faith in the world's most powerful economy. Those are among the implications, both sudden and long-lasting, expected to unfold if the U.S. defaults on debt payments for the first time in history.

Facing an August deadline for raising the country's borrowing limit or setting loose the consequences, politicians and economists are plenty alarmed. The people? Apparently not so much.

They're divided on whether to raise the limit, according to an Associated Press-GfK poll that found 41 percent opposed to the idea and 38 percent in favor.

People aren't exactly blase. A narrow majority in the poll expects an economic crisis to ensue if the U.S., maxed out on its borrowing capacity, starts missing interest payments to creditors. But even among that group, 37 percent say no dice to raising the limit.

In Washington's humid air, talk of a financial apocalypse is thick.

There are warnings of "credit markets in a state of panic," as the House Budget Committee chairman, Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., put it, causing a sudden drop-off in the country's ability to borrow and pushing the government off a "credit cliff."

He was characterizing a report by the government's nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office that warns of a "sudden fiscal crisis" in which investors might abandon U.S. bonds and force the government to pay steep interest rates and impose spending cuts and tax increases far more Draconian than if default were avoided.

The dire warnings appear to be falling on unconvinced ears, at least so far.

Call it doomsday fatigue.

In recent times, Americans heard that things were going to go haywire with the turn of the millennium, and they didn't. They were primed for post-Sept. 11 terrorist plots that did not unfold.

They've seen Congress, a lumbering body that gets fleet of foot at the last minute, come to the brink time after time, only to pull something out of its hat. Recently, a partial government shutdown was averted in that manner.

To Robin Knight, 50-year-old teacher from Gilbert, Ariz., who's trying to stay informed on the debt crisis, Washington's tendency to cry wolf and stage histrionics on issues of the day isn't helping.

"It should be very easy to understand," she said, "but I think there are so many skewed views and time given to people screaming that it can be hard to follow."

As during the lead-up to the government shutdown that didn't happen, tortured negotiations are under way.

Republican leaders are insisting on huge spending cuts as a condition for raising the debt limit. This position finds solid support from Republicans in the poll and backing from a plurality of independents.

President Barack Obama is pushing for increased tax revenue to be part of the deal, and that insistence led House Republican leader Eric Cantor of Virginia to walk out of the negotiations this past week.

About half of Democrats in the poll said the debt limit should be raised regardless of whether it's paired with a deal to cut spending.

The survey found no significant differences by education, age, income, or even by party, in perceptions of whether a crisis is likely if the limit is not increased. There was widespread dissatisfaction with how Obama is dealing with the deficit – a new high of 63 percent disapproval on that subject – and an even harsher judgment of how both parties in Congress are doing on the issue.

Full Article

Source: Huffington

No comments:

Post a Comment