|

| The author of America's new security state. |

The authors of the Patriot Act always intended that its provisions would be permanent. The politically expedient thing to do would have been to include a sunset provision, to acknowledge a temporary moment of crisis that required special measures for prosecutors to pursue terrorists. But the lawyers wanted no sunsets; some of them had been working

Al Qaeda cases since the first World Trade Center bombing and imagined a long-term struggle that could last a generation. “I said, ‘Don’t think of this as an emergency measure,’ ” Viet Dinh [

P1] recalled on July 20. At the time, Dinh was an assistant attorney general under John Ashcroft and was tasked on the morning of September 12 with writing a bill to fix whatever laws might impede investigation. The scholarship provided little guidance for how to make terror investigations easier, so Dinh sent an e-mail to the nation’s U.S. attorneys and FBI agents, asking for ideas. G-men are not constitutional lawyers, and excesses were rife: Someone wanted to send neighborhood watches in search of sordid types. The attorneys at Justice made piles, winnowing as they went: “Crazy Ideas,” “Quarter-Baked,” “Half-Baked.”

In those patriotic weeks, partisan conflict dissipated easily. The Democratic Senate and the Republican House each had their own bills, and Ashcroft, smiling, said every idea in each of the drafts would be adopted unless it conflicted with another provision. Jim Sensenbrenner, the bombastic, rotund Wisconsin Republican, leaned back in his chair and said his bill was called the USA Patriot Act. There were no conflicts with that; the name was in.

|

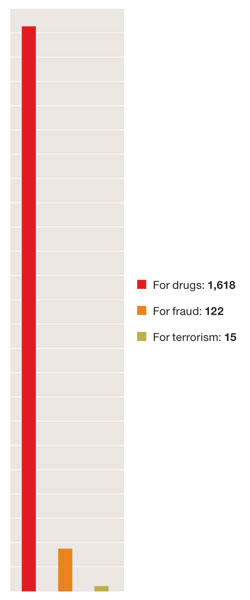

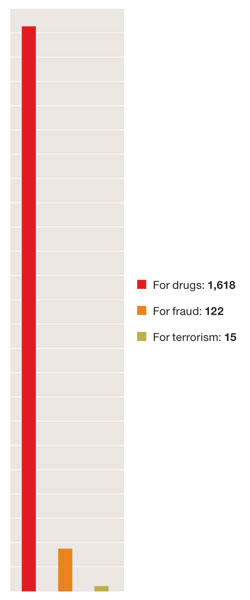

P2: Sneak-and-Peek

Delayed-notice search warrants issued under the expanded powers of the Patriot Act, 2006–2009. |

“Patriot Act” was appropriately overt. Before 9/11, when politicians spoke of “patriots,” they usually meant soldiers. Now prosecutors and the FBI were reaching for the same vanity—that they were the hard tip of freedom—and the same license to pursue enemies without much oversight or meddling. When it was signed into law six weeks after the attacks, the act made it easier to wiretap American citizens suspected of cooperating with terrorism, to snoop through business records without notification, and to execute search warrants without immediately informing their targets (a so-called sneak-and-peek [

P2]). Privileges once reserved for overseas intelligence work were extended to domestic criminal investigations. There was less judicial oversight and very little transparency. The bill’s symbolism mattered also, signaling that the moral deference previously given to the Special Forces would be broadened until it encompassed much of the apparatus of the American state. Local prosecutors, military policemen, CIA lawyers—these were indispensable patriots too.

The Patriot Act was mostly a Republican project at its origin, but it would have died long ago without the support of Democrats. Liberals were committed enough to the bill that it took Texas Republican Dick Armey to insist that the new privileges of the Patriot Act would indeed sunset, unless the president asked for, and Congress approved, a reauthorization. In 2005,

George W. Bush convinced Congress to renew the act, and in 2010, so did Barack Obama—even though the terrorist threat seemed less urgent, and liberal scholars had concluded that the civil-liberties violations in the bill could be resolved with a few modest changes. Dinh’s original worry—that politicians might not be committed enough to renew these laws—now seems misplaced.

What Dinh didn’t anticipate was a profound shift in liberalism and, therefore, in the politics of the country. Even with a Democrat now in the White House, the liberalism that protects the right of the individual against the majority—the politics of civil rights and abortion and gay marriage—has diminished, in favor of one that aims to improve the lot of the median man. Obama’s liberalism is for the majority, not against it. This spirit, and the unlikely endurance of the Patriot Act, owes something to the central psychological events of the decade: the vitality and threat of new economic competitors, the social violence initiated by the authors of obscure financial instruments, but first and most of all September 11—each of which evoked a particular feeling, that we were all together, under attack.

Origin

Source: New York Times