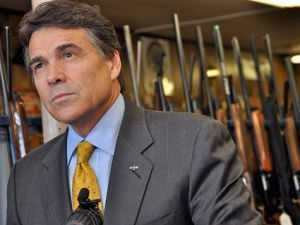

When MSNBC's Brian Williams asked Rick Perry during a recent GOP debate if he ever worried that his state had executed an innocent man on Perry's watch, the three-term Texas governor didn't hesitate: "No sir, I've never struggled with that at all." Maybe he should have: As Steve Mims and Joe Bailey detail in their new documentary, Incendiary, the state's 2004 execution of Cameron Todd Willingham for the murder of his two children was based in large part on arson science that had been thoroughly rejected by the scientific community—something that Perry had been informed of before the "ultimate justice" was served.

Inspired by David Grann's masterful 2009 New Yorker story about the case, the Austin filmmakers set out to chronicle the flawed forensics behind the execution. They soon found themselves in the middle of a pitched political battle involving Perry's apparent maneuvering to put a thumb on the scales with the Texas Forensic Science Commission. Mims and Bailey spoke recently with Mother Jones about the Willingham case, arson science, and how they navigated the politics of capital punishment.

Inspired by David Grann's masterful 2009 New Yorker story about the case, the Austin filmmakers set out to chronicle the flawed forensics behind the execution. They soon found themselves in the middle of a pitched political battle involving Perry's apparent maneuvering to put a thumb on the scales with the Texas Forensic Science Commission. Mims and Bailey spoke recently with Mother Jones about the Willingham case, arson science, and how they navigated the politics of capital punishment.

Mother Jones: What about Grann's story, and the case specifically, made you think "we need to make a film"?

Joe Bailey: I was so fascinated that the law and science and political forces were all animated in a life-and-death story. We saw that as a rare thing, and we thought that a documentary format allowed us the opportunity to explore the case in our own way and illustrate these things that seemed really fascinating—properties of fire, the human dynamic, and the appeals and petitions for clemency. We didn't expect it to erupt into this sort of political theater that it became: Just when we started making our film is when the shakeup of the Texas Forensic Science Commission happened, and it became sort of a dynamic and hilarious—darkly hilarious—struggle to document.

MJ: The centerpiece of the film, the forensics expert who explains why it wasn't arson, is Gerald Hurst. (He's the Willie Nelson figure in the trailer below.)

Steve Mims: At the time the fire happened and they investigated the fire scene for arson, the people who showed up there had been trained as arson investigators by other arson investigators, and they were using techniques that were derived from anecdotal observations about previous fires. It turns out none of the stuff was correct, and it wasn't really based on the scientific method—it was based on one fire investigator training another fire investigator how to look for signs that someone had poured fuel in a dwelling or something to set it on fire. At roughly the same time, the real science, which was already known, was being put into a document that was put out the next year, NFP 921.

MJ: So one year separated the junk science from the real science.

SM: That's the thing: It was known that this type of arson science is inaccurate, but it was formalized a year later. People have been able to characterize this case in ways that make [the science] seem marginal. Well, it's marginal to everybody but probably the guy who gets convicted.

JB: NFP 921 was published in January 1992. State of Texas v. Willingham didn't commence until that August.

SM: It hadn't percolated down to Corsicana, Texas, I guess.

JB: It definitely wasn't there during the investigation. But the timing is sort of eerie in a way. And you see Ernest Willis, for instance, being exonerated by the state of Texas under exactly the same circumstances on October 6th, 2004, and that's only months after Willingham's execution.

MJ: You have Gov. Perry, who when he talks about this issue, he calls the scientists "the latter-day supposed experts."

SM: They've also characterized Willingham as a "monster" over and over again (see video below). They came to be very methodical in terms of how they talk about the people involved in the investigation in that way.

JB: Hurst actually grew up in Oklahoma, but he decided to make his home in Texas. After he’d graduated from Cambridge and he'd already created an explosive molecule and a patent, the Defense Department was like, "Hey, where would you like to be—we'll give you the acreage and the space to conduct tests?" and he said, "Austin." Hurst is a perfect example of the conundrum for many people in Texas, the way that they laud scientific progress when it's profitable and the way that they discourage it when it comes to throwing criminal prosecutions into question. Hurst created astrolite explosives that are used in the development of oil and gas; it's used in shooting seismic, used in fracking oil and gas wells. He invented that.

He's pro-bono taking these cases and trying his best to make things right, and you have the governor basically trying to throw that into question for reasons that [seem] political or sad and dark. What's unique about the Willingham case is that if the scientific evidence isn't there, then the fire wasn't an arson. And if the fire wasn't an arson, then there isn't an arsonist to convict or to charge. That's where the rubber meets the road from a legal perspective, and I think most attorneys, and people who could call themselves scholars of the Constitution, should understand that. When you reduce it to a character test, that's a harder argument to win for someone like Willingham, who wasn't the shining example of a pillar of society.

SM: Another thing that kind of gets pushed away when people talk about the original event is how outrageous the case that the state made was: Around 9 a.m. on a weekday in December, Willingham got up and poured some kind of fluid all over his house and set it on fire. And when he did that, he decided not to put any shoes on, or a shirt, so the story you have to believe is he consciously ignited his house, without putting shoes or a shirt on, and ran outside and pretended that he'd only just woken up and he found the place in flames. And in that state, he intentionally burned himself.

Or you can believe what the guy says. There were all these witnesses to his behavior at the fire site: They had to restrain the guy from going back in. They had to handcuff him to a gurney so he would not endanger his life or the firefighters' life.

JB: They also claimed that he poured accelerant in an X pattern. I think the argument was made at one point that it was in a pentagram, and the prosecutor and the judge believed that he was a Satanist because he had heavy metal posters on the wall and skull tattoos on his arm.

MJ: Most fans of heavy metal manage to avoid that.

JB: Yeah, I think so. We offer in the film as a concession, that yeah, he probably hit his wife, and he's probably a pretty questionable character in a lot of ways. But not somebody necessarily who would murder his children by burning them alive. There's a huge leap in psychology between a pretty typical domestic dispute and psychopathic murderer. They were able to make that leap with a lot of cultural biases about rock and roll.

MJ: I was really struck by John Bradley, who is the district attorney appointed by Perry to chair the Forensic Science Commission. What was your interaction with him like?

SM: The first day we met him in Harlingen, Texas, where they held the first Forensic Science Commission meeting after he was appointed, he kicked us out of the meeting room. And he didn’t allow us back in until we were able to simultaneously show that it was a violation of the Texas Open Meetings Act and we had an attorney friend of ours call up the Attorney General's office in Austin and ask if he was going to have to get a court order to allow us back into the room. We realized we were not treated a lot differently than the people on the commission. Bradley kind of ran roughshod over people who were supposed to be his peers. He really made moves to consolidate power, and [stalled] the investigation of Willingham for about 19 months.

We are still both kind of dumbfounded by the whole thing. We've been on this for so long—way before Rick Perry thought about running for president as far as we know—and we've able to see it all unfold in front of us. We laid it out so that people could look at the whole thing and draw their own conclusion, but we can say for sure that a report that would have possibly been controversial was canceled.

MJ: And this is all happening down in Harlingen, Texas, which I don't think anyone outside of South Texas has heard of.

JB: It's about as far south as you can get in the United States. Generally the meetings are held in cities with large airports so that these professionals can fly in in the morning and fly out in the evening. That wasn't the case. That meeting was also held the same day as the Republican primary debate in Dallas, between Gov. Perry and Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, so I think the large portion of the press that would have been covering the case ended up in Dallas, covering the debate. So it seemed to add to John Bradley's ire when he walks into the room and sees Steve and me with two cameras set up and ready to go.

He is hard-nosed and doesn't have any qualms about stepping on people's toes and advocating his positions, and that includes stepping on some legal toes. A lot of eyebrows in Texas have been raised about his stance on the preservation of evidence. I couldn't imagine a better person from a tough-on-crime sort of lock 'em up, keep 'em locked up perspective to have. I couldn't imagine a shakier person to put on a commission that's put in charge of investigating forensic evidence.

MJ: What did the other members of the Forensic Science Commission make of him?

SM: At the first meeting in Harlingen I think they gave Bradley the benefit of the doubt—"We'll see how it goes"—and by the end of it didn't go very well. Bradley tried several strategies to get the Willingham case out of the Forensic Science Commission, and one of the things he tried to say was—and this is what eventually worked—that the commission didn't have the jurisdiction to consider the Willingham case because it happened before the beginning of the Forensic Science Commission in 2005, and that evidence was not handled by the state of Texas. And then eventually this past July the attorney general issued a ruling that basically said that's right.

MJ: David Martin, who is Willingham's first defense attorney, plays an interesting role in all of this. He actually wrote a letter to Perry asking him not to commute the sentence. What did he say when you first reached out to him?

JB: He seemed to me from the first time I talked to him to be an able attorney, a professional guy. I think now he's doing mostly insurance work. He was really cordial; he rode up on a mule when we got there, which was a little bit of a culture shock coming from Austin. He wanted to conduct the interview under the roof of the open-air barn, and it was August. We weren't sure whether he would rather have it inside but he said, no, this is the place to do it, we have to do it here. My wife, Alice, came, and she actually conducted most of the interview, which was great because she was really able to stick to the case and get straightforward answers. There are obviously points in the interview that you see in the film that the conversation takes a bizarre turn.

MJ: Your wife, Alice, is a prosecutor.

JB: I had her read the transcripts before we went up to Coriscana, and she prepared the questions. I think it was good to have her conducting the interview in a way because, you know, Martin is such a gentleman and sort of your classic cowboy or country attorney that he wasn't going to get angry with Alice. He was a lot more patient with her I would guess than he might have been with Steve or me.

MJ: Martin is adamant that his client did it, and he says it again in the film. What's driving that?

SM: He alludes to it in several places—that attorney-client privilege prevents him from telling people what Willingham told him, which he implies was a confession to the crime. He's really cagey the way he does this. Like, Joe asked him on camera, "Do you have some reason to believe—you seem to believe it pretty fervently; why?" He says, "Well, maybe I could tell you, but maybe attorney-client privilege prevents me from telling you."

One thing that we feel is some empathy for him, for everybody in Corsicana. They didn't ask to go to this house fire in December of 1991. Those guys showed up, and they put the fire out, and they did the investigation. And they probably executed the job on that day the way they understood the job. And then David Martin was appointed to take this job, and he probably did the job the way he thought he should do it. But what is wrong is that Willingham was on death row for 12 years, and in the intervening 12 years the evidence that was used to convict him, at least scientifically, was shown to be invalid.

All this happens while Willingham is sitting there in solitary confinement, 23 hours a day in a little box, one hour outside of it. You get down to the point where finally it gets to Hurst, who says ultimately you can't stand behind this testimony. And then [Willingham] gets executed.

MJ: One recurring theme in the film is the blurring of these two subjects—a debate about science becomes a debate about the death penalty. Is it possible to have one without the other?

JB: Aside from the political motivations that people may have, for their careers, or for appearances and how they've handled things, I think that ideologically it's a lot less nuanced of a conversation when you have pro- and anti- anything, especially pro- and anti-death penalty people wrangling over something—rather than having scientists explaining concepts to people about the way the fires behave.

MJ: Has anything positive come out of this?

JB: The Texas Fire Marshal's office has agreed to work with the commission to review past cases where there are questions, which is phenomenal. At the same time, it doesn't seem that they will proceed much further with the Willingham investigation because, in light of the attorney general's opinion, the individual commissioners could subject themselves to a lawsuit if they were to exceed their jurisdiction.

MJ: And Bradley ended up being denied by the Texas Senate from serving another term. Did your views change at all?

JB: A documentary lets you try to get behind the eyes of people and try to think about where they're coming from. We wanted to try to explore that mystery, and we weren't interested in making an advocacy piece or a political film. We came at the film enamored with the enigma: We were fascinated by the fact that scientists were unanimous in declaring that there was no evidence of arson, and yet people that were close to the case were very convinced that Willingham was guilty.

Origin

Source: Mother Jones

No comments:

Post a Comment