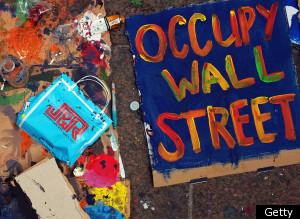

NEW YORK -- Americans have become so accustomed to our political and economic aspirations yielding only frustration, that we are rightfully inclined to dismiss as impotent the spectacle in the tiny park near Wall Street, where a few hundred people are camped out demanding various versions of change.

The scene feels familiar. There are grungy kids in sleeping bags arrayed on stained pieces of cardboard on the pavement. There are sign-wavers -- "PEOPLE, NOT PROFITS" -- and a handful of aging hippies on the periphery.

The cynic has plenty of material to work with, not least the fact that this inchoate, largely spontaneous gathering is fueled by so many issues -- economic inequality, war in Afghanistan, the unemployment and foreclosure crises, a lack of justice for the Wall Street chieftains who led the country into a ditch. At the same time, this movement lacks a clearly delineated set of demands. Ask the protesters what they want and prepare for a barrage of answers.

But that lack of definition to the agenda is no disqualifier. Indeed, it may be a source of strength and inclusion, as well as an indication of the depth and breadth of the dissatisfaction eating away at contemporary American society.

Beneath the familiar trappings of a youth-led protest movement, a current of unhappiness is rising to the fore, challenging the apathy that afflicts the country despite the steady erosion of economic opportunities for the vast majority of working people. If a sustained challenge to apathy is all this group can ultimately muster, that counts for something.

On Friday morning, Robert James Carlson -- his face clean-shaven, his reddish blonde hair clipped short and business-like -- stands on the northwest corner of Zuccotti Park, the headquarters for the Occupy Wall Street movement. He wears a pressed white shirt and a striped tie. A dollar bill is pressed across his mouth, held in place by duct tape.

Carlson is an accountant who lives in Jersey City, and he has been here for six days, drawn to the protests, he says, out of desire to lend his voice to calls for changes to the financial system so as to limit the threat of another debilitating shock. He hopes new rules will come that regulate dangerous speculation before another crisis materializes.

He rattles off the threats assailing ordinary life -- state finances plunging, leading to layoffs and cuts to basic services; the federal postal system warning of imminent bankruptcy, risking pensions.

"Does it have to get to the point where retired postal workers are in homeless shelters before we take action?" he asks. "The way our system works, it seems as if something has to melt down or break before the system finally changes. If a meltdown does happen, it's not going to be good."

But what sort of change is he demanding exactly? He seems amused by this question. The point is to crystallize a dialogue with the people able to take effective action, to prod the political system to focus on the right questions. He is no the answer man.

"I'm a 25-year-old kid," Carlson says. "If you're honestly expecting answers from a 25-year-old kid ..." His voice trails off. "What we're trying to do is get answers. We're very educated people and these problems are very complicated and it's gotten to the point where there are serious repercussions. We can't deny this anymore. We're a very prideful country, and it's hard for people to admit that our system is not working."

Susie and Artie Ravitz stand next to Carlson. Retirees from Easton, Pa., they have driven here for the day to add to the numbers.

"The main thing is to draw attention to the disparities," she says. "The rich and the greedy are taking the country down. It's really a discouraging time. You have young people with college degrees left out in the cold, unable to find jobs. I have kids and grandchildren. I really worry what their lives are going to be like."

As she speaks, a group of tourists from Shanghai gathers around, snapping photos of Carlson and the dollar bill taped over his mouth. One of the Chinese tourists gives a thumbs up. "We support freedom," he says later, when asked, before the minder of his mainland Chinese tourist group hurriedly leads him away.

So many issues, and so little coherence, one wants to say. Pick one or two and organize on those.

During the Vietnam War, protesters laid out a goal that could fit on a bumper sticker, leaving no confusion about the aims: Bring the troops home now. During the civil rights movement, participants organized around the moral imperative to dismantle a racist system of laws. Women's suffrage activists could declare victory when women got to vote.

The people in the park seem so disorganized in their aims, their talking points a hodgepodge paralleling the social media platforms -- Twitter, Facebook -- that has gained their fledgling movement attention: a little tax justice talk here, a bit of job creation there.

But this is only the beginning, says Ben Yost, a 36-year-old social worker from Brooklyn. He is here waving a sign that has check marks next to: WAR IN IRAQ. RECESSION. UNEMPLOYMENT. WAR IN AFGHANISTAN. Then a question: WHO'S MAKING MONEY? WALL STREET PROFITEERS.

This is the attention-getting moment before the agenda-setting phase, he says. "We need to just get a conversation growing and build a community and figure out how to get some of the money out of the corporations and back to the people who deserve it."

Yes, he says, organizing to pull troops out of war or take down Jim Crow laws makes for greater coherence, but those movements also involved taking on deep rifts in American society. Large numbers of people supported the war in Vietnam as a necessary challenge to the supposed falling dominoes of the Cold War. The segregationist order in the American South was intimately tied to a racist conception of culture and fear of the other, along with the economic privileges that accrued to being white.

The issues that have drawn people to Wall Street may be nebulous, with no obvious or agreed upon solutions, but they collectively amount to something that is not only a crisis, but also one that is incumbent upon the vast majority of Americans: The breakdown of the traditional middle class economic bargain -- the idea that people willing to work are rewarded with a reasonable standard of living.

The mostly young people occupying the park here do not boast expertise in the problems at hand anymore than they lay claim to obvious solutions, which, come to think of it, is rather endearing. But they are well versed in the basic complaint of the day, one that resonates in communities across the United States. For decades, well-connected people on Wall Street have taken home the lion's share of the spoils from American commerce, leaving inadequate scraps for everyone else. That needs to be fixed, or a nation once synonymous with abundant opportunity risks sliding into dysfunction. They are here because they have a sense that we have collectively been cheated of our legacy as Americans -- participants in a noble, national experiment that has enriched generations of people, yet has been perverted by an uber-rich elite and their hired agents in Washington.

What do they all want? It's a natural question, yet the lack of clear answer does not invalidate the ferment that has spawned this movement.

"I'm here wondering the same thing," says Yost. "But I'm sick of staying at home and watching the Daily Show, and this is kind of my first step. I don't want to go down without speaking my voice."

The trained news person in me is inclined to focus on what will come of all this: Probably not much. People may be affected by widespread economic crisis, but they are busy with their day-to-day lives and see no point in participating in futile street theater.

The election of Barack Obama felt like the culmination of a powerful movement for change, yet three years later many participants feel let down and even tricked, as the administration continues many of the policies of its predecessor and mounts tepid and ineffective responses to high unemployment and foreclosure. Populist outpouring has a checkered history in this country and everywhere else, most recently spawning a Tea Party movement that has almost single-handedly stymied every meaningful effort to address the economic challenge. Distrust and even cynicism do not come from nowhere.

These protests will probably peter out and be forgotten, recalled at most as footnotes to an age of diminishing expectations and the turmoil it is sowing.

And yet wouldn't it be better if that proves to be wrong?

The people in the park are not revolutionaries. They are calling for things that are far short of radical -- wages enough to pay for health care and housing; a tax code that taps a fair share from the wealthiest to finance retirement funds and public education.

"I think it's got potential," says Bob Broadhurst, a fourth-generation electrician who has driven down from the Boston area for a look. We need to get back to a functioning democracy. The 99 percenters, we've got to have a voice."

Origin

Source: Huffington

The scene feels familiar. There are grungy kids in sleeping bags arrayed on stained pieces of cardboard on the pavement. There are sign-wavers -- "PEOPLE, NOT PROFITS" -- and a handful of aging hippies on the periphery.

The cynic has plenty of material to work with, not least the fact that this inchoate, largely spontaneous gathering is fueled by so many issues -- economic inequality, war in Afghanistan, the unemployment and foreclosure crises, a lack of justice for the Wall Street chieftains who led the country into a ditch. At the same time, this movement lacks a clearly delineated set of demands. Ask the protesters what they want and prepare for a barrage of answers.

But that lack of definition to the agenda is no disqualifier. Indeed, it may be a source of strength and inclusion, as well as an indication of the depth and breadth of the dissatisfaction eating away at contemporary American society.

Beneath the familiar trappings of a youth-led protest movement, a current of unhappiness is rising to the fore, challenging the apathy that afflicts the country despite the steady erosion of economic opportunities for the vast majority of working people. If a sustained challenge to apathy is all this group can ultimately muster, that counts for something.

On Friday morning, Robert James Carlson -- his face clean-shaven, his reddish blonde hair clipped short and business-like -- stands on the northwest corner of Zuccotti Park, the headquarters for the Occupy Wall Street movement. He wears a pressed white shirt and a striped tie. A dollar bill is pressed across his mouth, held in place by duct tape.

Carlson is an accountant who lives in Jersey City, and he has been here for six days, drawn to the protests, he says, out of desire to lend his voice to calls for changes to the financial system so as to limit the threat of another debilitating shock. He hopes new rules will come that regulate dangerous speculation before another crisis materializes.

He rattles off the threats assailing ordinary life -- state finances plunging, leading to layoffs and cuts to basic services; the federal postal system warning of imminent bankruptcy, risking pensions.

"Does it have to get to the point where retired postal workers are in homeless shelters before we take action?" he asks. "The way our system works, it seems as if something has to melt down or break before the system finally changes. If a meltdown does happen, it's not going to be good."

But what sort of change is he demanding exactly? He seems amused by this question. The point is to crystallize a dialogue with the people able to take effective action, to prod the political system to focus on the right questions. He is no the answer man.

"I'm a 25-year-old kid," Carlson says. "If you're honestly expecting answers from a 25-year-old kid ..." His voice trails off. "What we're trying to do is get answers. We're very educated people and these problems are very complicated and it's gotten to the point where there are serious repercussions. We can't deny this anymore. We're a very prideful country, and it's hard for people to admit that our system is not working."

Susie and Artie Ravitz stand next to Carlson. Retirees from Easton, Pa., they have driven here for the day to add to the numbers.

"The main thing is to draw attention to the disparities," she says. "The rich and the greedy are taking the country down. It's really a discouraging time. You have young people with college degrees left out in the cold, unable to find jobs. I have kids and grandchildren. I really worry what their lives are going to be like."

As she speaks, a group of tourists from Shanghai gathers around, snapping photos of Carlson and the dollar bill taped over his mouth. One of the Chinese tourists gives a thumbs up. "We support freedom," he says later, when asked, before the minder of his mainland Chinese tourist group hurriedly leads him away.

So many issues, and so little coherence, one wants to say. Pick one or two and organize on those.

During the Vietnam War, protesters laid out a goal that could fit on a bumper sticker, leaving no confusion about the aims: Bring the troops home now. During the civil rights movement, participants organized around the moral imperative to dismantle a racist system of laws. Women's suffrage activists could declare victory when women got to vote.

The people in the park seem so disorganized in their aims, their talking points a hodgepodge paralleling the social media platforms -- Twitter, Facebook -- that has gained their fledgling movement attention: a little tax justice talk here, a bit of job creation there.

But this is only the beginning, says Ben Yost, a 36-year-old social worker from Brooklyn. He is here waving a sign that has check marks next to: WAR IN IRAQ. RECESSION. UNEMPLOYMENT. WAR IN AFGHANISTAN. Then a question: WHO'S MAKING MONEY? WALL STREET PROFITEERS.

This is the attention-getting moment before the agenda-setting phase, he says. "We need to just get a conversation growing and build a community and figure out how to get some of the money out of the corporations and back to the people who deserve it."

Yes, he says, organizing to pull troops out of war or take down Jim Crow laws makes for greater coherence, but those movements also involved taking on deep rifts in American society. Large numbers of people supported the war in Vietnam as a necessary challenge to the supposed falling dominoes of the Cold War. The segregationist order in the American South was intimately tied to a racist conception of culture and fear of the other, along with the economic privileges that accrued to being white.

The issues that have drawn people to Wall Street may be nebulous, with no obvious or agreed upon solutions, but they collectively amount to something that is not only a crisis, but also one that is incumbent upon the vast majority of Americans: The breakdown of the traditional middle class economic bargain -- the idea that people willing to work are rewarded with a reasonable standard of living.

The mostly young people occupying the park here do not boast expertise in the problems at hand anymore than they lay claim to obvious solutions, which, come to think of it, is rather endearing. But they are well versed in the basic complaint of the day, one that resonates in communities across the United States. For decades, well-connected people on Wall Street have taken home the lion's share of the spoils from American commerce, leaving inadequate scraps for everyone else. That needs to be fixed, or a nation once synonymous with abundant opportunity risks sliding into dysfunction. They are here because they have a sense that we have collectively been cheated of our legacy as Americans -- participants in a noble, national experiment that has enriched generations of people, yet has been perverted by an uber-rich elite and their hired agents in Washington.

What do they all want? It's a natural question, yet the lack of clear answer does not invalidate the ferment that has spawned this movement.

"I'm here wondering the same thing," says Yost. "But I'm sick of staying at home and watching the Daily Show, and this is kind of my first step. I don't want to go down without speaking my voice."

The trained news person in me is inclined to focus on what will come of all this: Probably not much. People may be affected by widespread economic crisis, but they are busy with their day-to-day lives and see no point in participating in futile street theater.

The election of Barack Obama felt like the culmination of a powerful movement for change, yet three years later many participants feel let down and even tricked, as the administration continues many of the policies of its predecessor and mounts tepid and ineffective responses to high unemployment and foreclosure. Populist outpouring has a checkered history in this country and everywhere else, most recently spawning a Tea Party movement that has almost single-handedly stymied every meaningful effort to address the economic challenge. Distrust and even cynicism do not come from nowhere.

These protests will probably peter out and be forgotten, recalled at most as footnotes to an age of diminishing expectations and the turmoil it is sowing.

And yet wouldn't it be better if that proves to be wrong?

The people in the park are not revolutionaries. They are calling for things that are far short of radical -- wages enough to pay for health care and housing; a tax code that taps a fair share from the wealthiest to finance retirement funds and public education.

"I think it's got potential," says Bob Broadhurst, a fourth-generation electrician who has driven down from the Boston area for a look. We need to get back to a functioning democracy. The 99 percenters, we've got to have a voice."

Origin

Source: Huffington

No comments:

Post a Comment