Rodney Robinson, a single father in Los Angeles, needs government help to pay his rent. But getting that help from the state of California involves sharing the money with some of the nation’s largest banks or check cashing services.

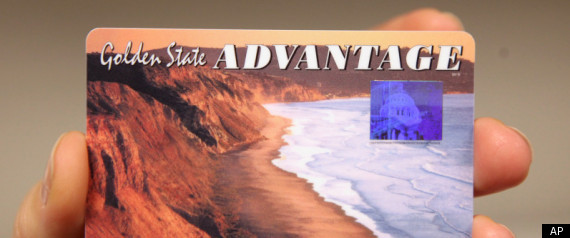

Rodney Robinson, a single father in Los Angeles, needs government help to pay his rent. But getting that help from the state of California involves sharing the money with some of the nation’s largest banks or check cashing services.The state distributes public assistance through so-called EBT cards, which look and work much like debit cards. But Robinson's neighborhood in South Los Angeles has only three places that allow him to use that card to withdraw enough cash to cover his monthly rent free of charge. He can visit any bank ATM, but that entails charges of as much as four dollars per transaction. A local check cashing chain charges $1.75. Grocery stores will let him withdraw cash, but only after a purchase.

"Those are your options, in this neighborhood anyway," said Robinson, 43, who has resigned himself to surrendering part of his $317-per-month check for lack of other options. "I can either pay the fee, or go buy several packs of gum to get the money and suck up a different kind of waste."

Across much of the nation, administering relief programs such as unemployment benefits and emergency rental assistance has become an increasingly substantial profit center for banks and other financial services firms, according to analysts. Like California, many states have contracted with private companies to distribute these funds. While the contracts have saved states millions of dollars in costs previously incurred for printing and mailing out checks, the agreements often give companies the ability to extract fees from recipients -- some of the nation’s most vulnerable families.

"We are talking about people living well below the poverty line, who need every penny to survive," said Diana Spatz, executive director of LIFETIME, a California-based nonprofit that helps poor families qualify for assistance then gain self-sufficiency. Spatz is herself a former welfare recipient.

The average cash grant in California amounts to $458.24, or $5,498.88 a year, and supports a family of three, according to state data. The federal government considers a family of three poor if it’s annual income amounts to less than $18,530. California’s assistance program typically leaves families living on less than 50 percent of the federal poverty line, and usually with little extra cash.

California’s agreement with Affiliated Computer Services, a Dallas-based division of Xerox, to distribute cash welfare assistance, aid for international refugees, utility grants and other emergency support cost the state's poor nearly $17.4 million in surcharges and fees last year, according to California Department of Social Services data. The spoils went to ACS and many of the nation’s largest banks.

ACS asserts that it is doing right by state taxpayers and the people who count on it for their disbursements.

"We provide a quality service that helps states save money and gives benefit recipients secure access to cash," said Kenneth Ericson, a company spokesman, from his office in Washington, D.C.

Under the terms of the contract with ACS, California’s poor families can request cash back after making purchases at many stores. Four times a month, they can use a network of ATMs owned mostly by credit unions without incurring a charge. After that, ACS assesses an 80 cent fee each time an EBT card holder visits any ATM. People receiving public assistance can also use the phone or Internet to check their account balances free of charge, but they surrender 25 cents each time they do so at an ATM.

On one of its websites, the state publishes a searchable list of ATMs that benefit recipients may use free of charge. At the county level, social services staff also hand applicants lists of free ATMs available in the local area.

"We really make every effort to ensure that California families have free access to their benefits," said Michael Weston, a spokesman for the California Department of Social Services.

But advocates for the poor say ACS’s network of free ATMs is far too limited. Most belong to credit unions or community banks that operate one to three machines -- unlike major banks, which maintain hundreds of cash machines in multiple cities. In most retail stores, customers can only request cash back in multiples of $20, with a maximum withdrawal of $200 per transaction, according to five people receiving cash benefits in California. In many stores, the cash back limits fall around $80.

At the same time, items people most often use their cash benefits to cover -- necessities such as rent, utilities and phone bills -- often run more than $200, which effectively forces many poor people to pay fees and surcharges to access their benefits, say advocates.

"Millions of dollars that California families need for basic necessities, millions intended to help poor people in this state, are instead going to banks and processors in surcharges and fees," said Jessica Bartholow, a legislative advocate at the Sacramento-based non-profit advocacy group, the Western Center On Law and Poverty.

Electronic benefit cards, or EBTs, are a relatively new phenomenon. In 1996, when then President Bill Clinton signed legislation overhauling welfare, a little known provision required that states gradually phase out paper food stamps and instead provide electronic access to food aid. The cards were supposed to cut food stamp printing and mailing costs and help reduce fraud.

Over the next 15 years, states began handing contracts to banks and other companies to manage additional forms of public assistance via the new cards.

For the financial institutions, the change opened a potentially lucrative avenue: While federal law bars retailers, banks and other companies from collecting fees or surcharges for handling food stamp benefits that are loaded onto EBT cards, that provision does not apply to cash assistance programs.

ACS has been in the business of providing access to public benefits for more than 15 years and currently has contracts with 16 states, including Ohio, Massachusetts and Virginia, said Ericson, the company spokesman.

Four years ago, ACS won a contract to provide benefits access to welfare recipients in California through 2015. ACS secured the state’s business with a proposal that pledged to save the state an estimated $20 million compared to other bids. JP Morgan Chase had previously provided the same services.

Under the terms of the contract, California pays ACS 60 cents per month to load any type of cash assistance onto an EBT card and $1.17 per month when the company loads both food stamps and cash benefits. In September, some 76,000 families were receiving only cash aid and 623,500 families were receiving both cash and food assistance. As a result, California paid ACS $775,095 for maintaining its EBT system that month.

The number of families receiving assistance fluctuates each month, so it is difficult to say how much the company will earn this year or over the life of the contract for loading benefits. And, ACS’s earnings are not reported separately in Xerox’s public earnings statements.

But state data does show that ACS collected $806,238 in fees from California’s public benefit recipients over the first eight months of this year. And banks collected about $12.9 million in ATM surcharges from many of California’s poor families during that same time.

In September 2010, the California Department of Social services sent letters to companies that own and operate large ATM networks such as Wells Fargo, Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase and Cardtronics, as well as financial industry trade groups, such as the California Banker’s Association, the California Credit Union League. The letters asked the banks and the trade group’s member institutions to waive surcharges for EBT card users at their ATMs.

None of the banks complied, Weston said.

That doesn’t surprise Robinson. The poor aren’t a public priority, he said.

"Mention welfare and people usually start talking about fraud, the fraud they think they’ve seen at the store, people in casinos, the people they think don’t deserve benefits," Robinson said. "There’s just this assumption that we’re all a problem."

In 2010, California's governor directed ACS to block ATMs inside strip clubs and casinos after a Los Angles Times story revealed that welfare recipients had pulled $4.8 million off of EBT cards in casinos over the course of nearly three years, the newspaper reported. In that same period, poor people pulled about $12,000 out of ATMs stationed at strip clubs.

Back in 2006, Robinson was working full time in an airplane parts factory. His commute was 40 miles round trip. The cost of gas was soaring. Robinson’s electricity was cut off more than a few times, he said. So, he decided it was time for a big change. He left his job and went back to college. When Robinson got a divorce in 2009, he took a part-time job in the school’s business office so that he could also care for his now six-year-old daughter. Welfare is a temporary crutch Robinson used to keep his daughter out of a lifetime of poverty, he said.

But, when California trimmed its welfare eligibility timeline from five years to four this year, Robinson lost his benefits. Now, he is receiving $317 in cash assistance for his daughter and $300 in food stamps to keep her fed. Robinson had to take out additional student loans to get by. There have been times when he’s needed help from family or friends. But this spring, he will graduate.

"I honestly don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the fees. They are there. They are not going anywhere," Robinson said before learning ACS and banks collected more than $17 million from welfare recipients last year. "But, you know, it does seem like somebody has made sure everybody’s needs get met unless you are a somebody with very little money. And that would be me."

Origin

Source: Huff

No comments:

Post a Comment