ST. THOMAS, Ont. — If there is any doubt that the erosion of unions could be contributing to the decline of the middle class — and, by extension, Canada's growing rich-poor divide — consider Shane MacPherson's career prospects.

When MacPherson stepped onto the line at the Ford Motor Co. assembly plant in St. Thomas, Ont., in the mid-'90s, he counted himself among the lucky ones. After decades of deterioration, good factory jobs had grown scarce, and, as the son of a Ford worker, MacPherson took comfort in knowing he would be able to provide his family with the same financial security his parents had given him.

"It was like, 'You're here. You're not switching jobs. This is it,' says MacPherson, whose sense of security grew even more when his wife got a job at Ford. "We weren't going to worry about the things that some people worry about."

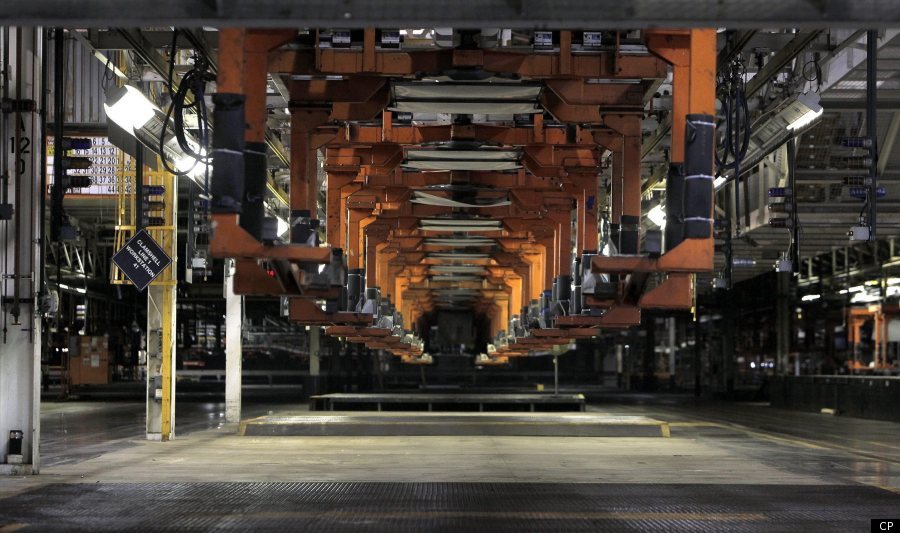

Of course, all that changed in 2009, when the beleaguered Detroit firm announced it was closing the plant in St. Thomas, vaporizing 1,000 jobs and pulling the rug out from under MacPherson's vision for the future.

"I've been looking for a job for over a year and a half — and it's not happening," says the 35-year-old father of three, who will be removed from Ford's callback list at the end of the month. "Me and my wife realize that life's going to be completely different than what we imagined it was going to be."

"Unions are a major force for greater income equality at the national and local level," says Stephanie Ross, a labour expert at York University. "Through collective bargaining, they basically turn bad jobs into better jobs; into jobs that have a decent wage that can sustain a certain standard of living."

So it should come as no surprise that the diminishing capacity of organized labour appears to be having the opposite effect.

According to a recent Harvard University study, the disintegration of unions has been a significant factor in the growth in income inequality in the United States. Using data from the Current Population Survey, researchers decomposed the growth in hourly wages inequality for private sector workers from 1973 to 2007, when union membership plummeted from 34 per cent to 8 per cent. They concluded that the decline of organized labour explains a fifth to a third [of] the growth in inequality — an effect comparable to the stratification of wages by education.

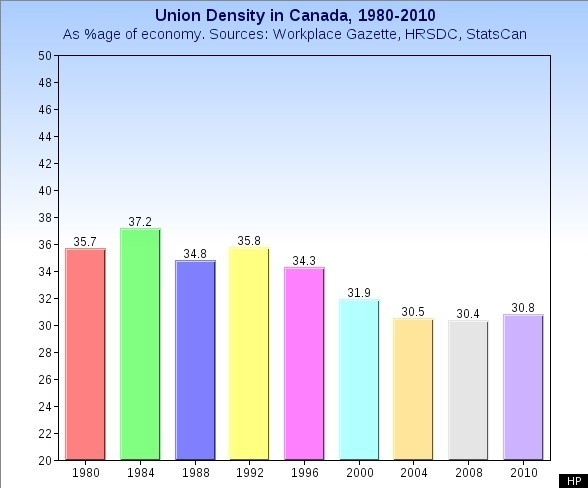

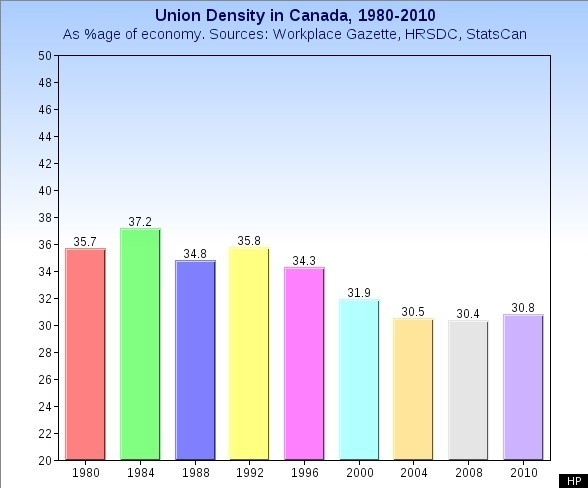

Though the trend has not been as pronounced in Canada, experts say the fallout has been similar.

According to Craig Riddell, a labour economist at the University of British Columbia, in recent decades, fully 20 per cent of the growth in income inequality among Canadian men can be attributed to the decline in union density. The link, he says, is particularly apparent in the private sector, where the drop-off has been most pronounced.

For better or worse, observers tend to chalk up the decline of unions — and many of the industries where labour was once strongest — to some combination of a changing world economy, competition from cheap imports and the unsustainable nature of big unions themselves.

But for those born and raised to work on the line, the implications of this particular aspect of the growing income gap are more than an abstraction. As a gulf opens up between their expectations and reality, their sense of community and personal identity hangs in the balance.

"We don't go and get a big education and move to Toronto for the big jobs," says Ron Drouillard, a fourth-generation Ford worker who was laid off in 2007 when the company announced it was closing a Windsor, Ont., plant.

"[People] go into the factory when they're 18 or 19, and that's their sacrifice, that's their education. It's going to take a toll on their bodies and they're going to die a little bit younger, but that's going to provide a better life for their kids. This is what we do," he says, pausing briefly before correcting himself. "Well, it's what we did."

'NO REASON' FOR MIDDLE CLASS JOBS

According to Jim Stanford, chief economist for the Canadian Auto Workers' union, the role labour organizations played in smoothing out income disparity in the 20th century cannot be overstated.

"There's no inherent reason in any profession or in any industry why middle class jobs would normally be produced by the market economy," he says. "Middle class jobs are a creation of deliberate efforts to lift standards, and unions are the most important of those efforts."

Peter Temin, an expert in economic history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sees it somewhat less starkly. Noting that the rise of unions during the 1930s occurred alongside a host of other redistributive public policies, he says they have been more significant in maintaining equality than creating it.

"Income inequality was reduced a lot in the Second World War, and the unions preserved it for a generation," he says.

But either way, it's clear that there's something about unions that is conducive to flattening the income distribution — and not just for those who pay membership dues.

For all of Big Labour's shortcomings, the evidence is ample that the collective agreements negotiated by union bosses tend to bid up wages throughout the entire sector, as management strives to retain employees and discourage unionization.

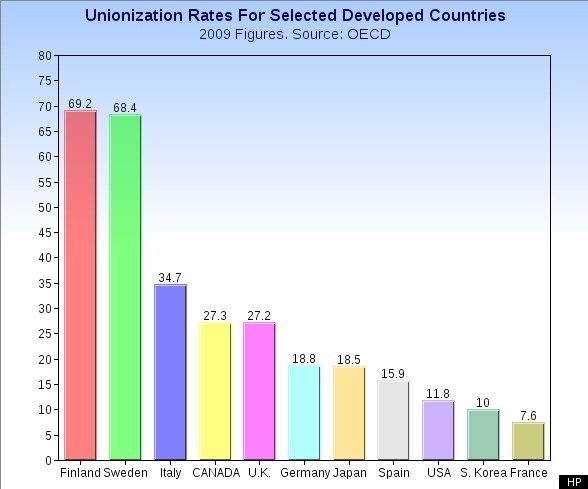

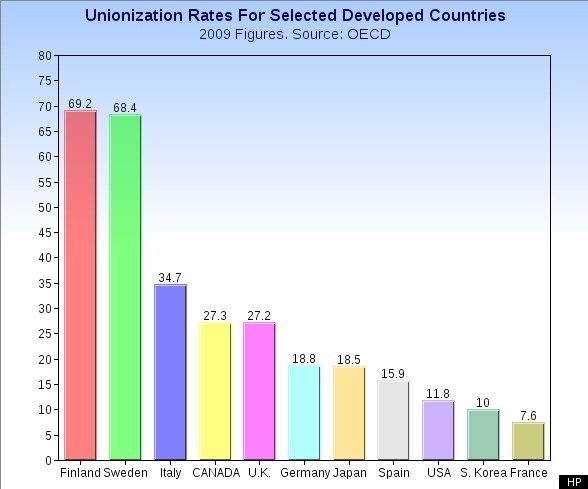

At the same time, studies have shown that in industrialized nations, high union density often accompanies a variety of other equalizing measures, including progressive taxation and robust labour laws.

Within unionized shops, says Riddell, unions have tended to lift the earnings of those at the bottom and compress incomes at the top — an equalizing effect that is most pronounced in the kind of private sector unions where the decline has been concentrated.

"You had a lot of unskilled, and semi-skilled workers whose wages moved up into earnings that put them into the middle class, so you had a much more homogeneous society, income-wise, than you would have otherwise had," Riddell says of auto towns like St. Thomas and Windsor.

For many in those cities, generations of relatively solid pay, benefits and job security engendered an almost institutionalized belief in the promise of landing a union gig.

As Drouillard points out, when he was in his final year of high school, his vice-principal reminded him that the Big Three were hiring.

"He was questioning me, 'Why are you still here?' " recalls the 37-year-old, who started at Ford in the mid-'90s. "They pressured you to go [because] that's the best job you'll ever get. If you're going to live in this community, quit school and go to the factory. That was normal."

Which could explain why these plants became communities all their own.

"One of the neatest things was that we had our own hockey league, not just a hockey team," says MacPherson. "We had our own league with just our plant."

Michelle Gleeson, who was a second-generation Ford worker in St. Thomas, also describes a culture of togetherness.

"It wasn't the drone syndrome, where you just go to work and you're like a robot," she says. "It was more like a family, and I loved that."

The auto workers in Windsor and St. Thomas say they always suspected on some level that their jobs wouldn't last forever — and this fear was not unwarranted. Even before the recession, Canada's auto industry was falling of the cliff, shedding a staggering 56,000 jobs from 2004 to 2008.

As the rumours became harder to ignore, the threat of shutdown gnawed away at the ties forged on the factory floor and in the union hall.

"It's almost like [we] couldn't take out their anger or their power on the employer anymore so it just kind of turned on ourselves," says Drouillard.

But animosity soon gave way to grief.

"There was obviously a big sense of loss," says Dennis McGee, president of CAW Local 1520, which represents Ford workers in St. Thomas. "[It's like] you've lost a family member."

WEARING DOWN THE UNION LABEL

In a recent report on deepening income disparity, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) noted that, in Canada, more than 40 per cent of the increase in inequality since the 1980s can be attributed to the "rising gap in men's earnings."

"Employment is the most promising way of tackling inequality," the OECD maintained. "The biggest challenge is creating more and better jobs that offer good career prospects and a real chance for people to escape poverty."

But as labour share's of GDP falls and corporate profits increase, it's difficult to see where those jobs will come from, or what role unions might play in this effort.

Whereas the Great Depression ushered in a progressive political atmosphere that was conducive to the rise of unions and the redistribution of income, the recent recession has left a very different legacy in its wake.

In the private sector, experts say that the passage of restrictive laws around union organizing and shifting employer attitudes are making it tough for unions to lay down roots, particularly in the growing service sector.

Unlike big plants, which contained hundreds of full-time employees under the same roof, restaurants and retail outlets tend to be staffed by temporary and part-time workers scattered over many locations.

"It's been very difficult for unions to organize the Walmarts, and not just because Walmart goes out of its way to prevent unionization," says Riddell. "Even when unions have made some in-roads, they've either not been able to get a first collective agreement or survive."

Despite repeated organizing drives, a Walmart in Weyburn, Sask., is the only unionized location in North America.

At the same time, as governments trumpet the virtues of austerity and push privatization as a means to trim the fat, public sector unions — the last stronghold of organized labour in Canada — are increasingly coming under attack, as the threat of cutbacks loom everywhere from city hall to Parliament Hill.

In the U.S., observers often cite the infamous Reagan-era firing of 11,000 striking air traffic controllers as the moment the tide turned against unions.

On this side of the border, Dalhousie University economist Lars Osberg says the Harper government's swift intervention in the recent Canadian Union of Postal Workers and Air Canada labour disputes may one day be seen as a similar turning point.

"If you want a direct indicator of the political power of unions," he says, "that's an indicator."

But however the labour market adjusts to the New World Order, it seems unlikely that the kind of work that once powered southern Ontario will ever return to the same extent, forcing legions of laid-off factory employees to ponder a tough choice: settle for less, or move somewhere else.

Meanwhile, in St. Thomas, the death rattle of CAW Local 1520 is taking place in a rented space at a nondescript strip mall a few minutes from the plant, where the union and government have funded an "action centre" for workers to spruce up their resumes, peruse job boards and find support in one another.

Since selling the old union hall a few months ago, the action centre has also become a kind of makeshift memorial. Framed portraits of the CAW's top brass and a photo of a Crown Victoria, the car that used to be built here, hang on the grey walls. Behind the door in his office, McGee has stacked several plaques marking significant milestones in the local's 44-year history.

As McGee explains, the plaques used to be mounted in concrete at the union hall, but are too heavy to hang.

The assembly plant is still impossible to miss from Highway 4, but the massive employee parking lot that extends to the road's edge now sits empty.

"I hate driving by there," says MacPherson, who passes the plant on a daily basis. "I just try not to look."

Origin

Source: Huff

When MacPherson stepped onto the line at the Ford Motor Co. assembly plant in St. Thomas, Ont., in the mid-'90s, he counted himself among the lucky ones. After decades of deterioration, good factory jobs had grown scarce, and, as the son of a Ford worker, MacPherson took comfort in knowing he would be able to provide his family with the same financial security his parents had given him.

"It was like, 'You're here. You're not switching jobs. This is it,' says MacPherson, whose sense of security grew even more when his wife got a job at Ford. "We weren't going to worry about the things that some people worry about."

Of course, all that changed in 2009, when the beleaguered Detroit firm announced it was closing the plant in St. Thomas, vaporizing 1,000 jobs and pulling the rug out from under MacPherson's vision for the future.

"I've been looking for a job for over a year and a half — and it's not happening," says the 35-year-old father of three, who will be removed from Ford's callback list at the end of the month. "Me and my wife realize that life's going to be completely different than what we imagined it was going to be."

More on income inequality at Mind The Gap: Which Provinces Have The Widest Income Gap?.. 11 Products And Services For The Super-Rich.. Calgary's Energy Boom Masks A Growing Gap.. FULL COVERAGE..MacPherson's struggle is a reminder of the gaping hole in the labour market that unionized jobs once occupied.

"Unions are a major force for greater income equality at the national and local level," says Stephanie Ross, a labour expert at York University. "Through collective bargaining, they basically turn bad jobs into better jobs; into jobs that have a decent wage that can sustain a certain standard of living."

So it should come as no surprise that the diminishing capacity of organized labour appears to be having the opposite effect.

According to a recent Harvard University study, the disintegration of unions has been a significant factor in the growth in income inequality in the United States. Using data from the Current Population Survey, researchers decomposed the growth in hourly wages inequality for private sector workers from 1973 to 2007, when union membership plummeted from 34 per cent to 8 per cent. They concluded that the decline of organized labour explains a fifth to a third [of] the growth in inequality — an effect comparable to the stratification of wages by education.

Though the trend has not been as pronounced in Canada, experts say the fallout has been similar.

According to Craig Riddell, a labour economist at the University of British Columbia, in recent decades, fully 20 per cent of the growth in income inequality among Canadian men can be attributed to the decline in union density. The link, he says, is particularly apparent in the private sector, where the drop-off has been most pronounced.

For better or worse, observers tend to chalk up the decline of unions — and many of the industries where labour was once strongest — to some combination of a changing world economy, competition from cheap imports and the unsustainable nature of big unions themselves.

But for those born and raised to work on the line, the implications of this particular aspect of the growing income gap are more than an abstraction. As a gulf opens up between their expectations and reality, their sense of community and personal identity hangs in the balance.

"We don't go and get a big education and move to Toronto for the big jobs," says Ron Drouillard, a fourth-generation Ford worker who was laid off in 2007 when the company announced it was closing a Windsor, Ont., plant.

"[People] go into the factory when they're 18 or 19, and that's their sacrifice, that's their education. It's going to take a toll on their bodies and they're going to die a little bit younger, but that's going to provide a better life for their kids. This is what we do," he says, pausing briefly before correcting himself. "Well, it's what we did."

'NO REASON' FOR MIDDLE CLASS JOBS

According to Jim Stanford, chief economist for the Canadian Auto Workers' union, the role labour organizations played in smoothing out income disparity in the 20th century cannot be overstated.

"There's no inherent reason in any profession or in any industry why middle class jobs would normally be produced by the market economy," he says. "Middle class jobs are a creation of deliberate efforts to lift standards, and unions are the most important of those efforts."

Peter Temin, an expert in economic history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sees it somewhat less starkly. Noting that the rise of unions during the 1930s occurred alongside a host of other redistributive public policies, he says they have been more significant in maintaining equality than creating it.

"Income inequality was reduced a lot in the Second World War, and the unions preserved it for a generation," he says.

But either way, it's clear that there's something about unions that is conducive to flattening the income distribution — and not just for those who pay membership dues.

For all of Big Labour's shortcomings, the evidence is ample that the collective agreements negotiated by union bosses tend to bid up wages throughout the entire sector, as management strives to retain employees and discourage unionization.

At the same time, studies have shown that in industrialized nations, high union density often accompanies a variety of other equalizing measures, including progressive taxation and robust labour laws.

Within unionized shops, says Riddell, unions have tended to lift the earnings of those at the bottom and compress incomes at the top — an equalizing effect that is most pronounced in the kind of private sector unions where the decline has been concentrated.

"You had a lot of unskilled, and semi-skilled workers whose wages moved up into earnings that put them into the middle class, so you had a much more homogeneous society, income-wise, than you would have otherwise had," Riddell says of auto towns like St. Thomas and Windsor.

For many in those cities, generations of relatively solid pay, benefits and job security engendered an almost institutionalized belief in the promise of landing a union gig.

As Drouillard points out, when he was in his final year of high school, his vice-principal reminded him that the Big Three were hiring.

"He was questioning me, 'Why are you still here?' " recalls the 37-year-old, who started at Ford in the mid-'90s. "They pressured you to go [because] that's the best job you'll ever get. If you're going to live in this community, quit school and go to the factory. That was normal."

Which could explain why these plants became communities all their own.

"One of the neatest things was that we had our own hockey league, not just a hockey team," says MacPherson. "We had our own league with just our plant."

Michelle Gleeson, who was a second-generation Ford worker in St. Thomas, also describes a culture of togetherness.

"It wasn't the drone syndrome, where you just go to work and you're like a robot," she says. "It was more like a family, and I loved that."

The auto workers in Windsor and St. Thomas say they always suspected on some level that their jobs wouldn't last forever — and this fear was not unwarranted. Even before the recession, Canada's auto industry was falling of the cliff, shedding a staggering 56,000 jobs from 2004 to 2008.

As the rumours became harder to ignore, the threat of shutdown gnawed away at the ties forged on the factory floor and in the union hall.

"It's almost like [we] couldn't take out their anger or their power on the employer anymore so it just kind of turned on ourselves," says Drouillard.

But animosity soon gave way to grief.

"There was obviously a big sense of loss," says Dennis McGee, president of CAW Local 1520, which represents Ford workers in St. Thomas. "[It's like] you've lost a family member."

WEARING DOWN THE UNION LABEL

In a recent report on deepening income disparity, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) noted that, in Canada, more than 40 per cent of the increase in inequality since the 1980s can be attributed to the "rising gap in men's earnings."

"Employment is the most promising way of tackling inequality," the OECD maintained. "The biggest challenge is creating more and better jobs that offer good career prospects and a real chance for people to escape poverty."

But as labour share's of GDP falls and corporate profits increase, it's difficult to see where those jobs will come from, or what role unions might play in this effort.

Whereas the Great Depression ushered in a progressive political atmosphere that was conducive to the rise of unions and the redistribution of income, the recent recession has left a very different legacy in its wake.

In the private sector, experts say that the passage of restrictive laws around union organizing and shifting employer attitudes are making it tough for unions to lay down roots, particularly in the growing service sector.

Unlike big plants, which contained hundreds of full-time employees under the same roof, restaurants and retail outlets tend to be staffed by temporary and part-time workers scattered over many locations.

"It's been very difficult for unions to organize the Walmarts, and not just because Walmart goes out of its way to prevent unionization," says Riddell. "Even when unions have made some in-roads, they've either not been able to get a first collective agreement or survive."

Despite repeated organizing drives, a Walmart in Weyburn, Sask., is the only unionized location in North America.

At the same time, as governments trumpet the virtues of austerity and push privatization as a means to trim the fat, public sector unions — the last stronghold of organized labour in Canada — are increasingly coming under attack, as the threat of cutbacks loom everywhere from city hall to Parliament Hill.

In the U.S., observers often cite the infamous Reagan-era firing of 11,000 striking air traffic controllers as the moment the tide turned against unions.

On this side of the border, Dalhousie University economist Lars Osberg says the Harper government's swift intervention in the recent Canadian Union of Postal Workers and Air Canada labour disputes may one day be seen as a similar turning point.

"If you want a direct indicator of the political power of unions," he says, "that's an indicator."

But however the labour market adjusts to the New World Order, it seems unlikely that the kind of work that once powered southern Ontario will ever return to the same extent, forcing legions of laid-off factory employees to ponder a tough choice: settle for less, or move somewhere else.

Meanwhile, in St. Thomas, the death rattle of CAW Local 1520 is taking place in a rented space at a nondescript strip mall a few minutes from the plant, where the union and government have funded an "action centre" for workers to spruce up their resumes, peruse job boards and find support in one another.

Since selling the old union hall a few months ago, the action centre has also become a kind of makeshift memorial. Framed portraits of the CAW's top brass and a photo of a Crown Victoria, the car that used to be built here, hang on the grey walls. Behind the door in his office, McGee has stacked several plaques marking significant milestones in the local's 44-year history.

As McGee explains, the plaques used to be mounted in concrete at the union hall, but are too heavy to hang.

The assembly plant is still impossible to miss from Highway 4, but the massive employee parking lot that extends to the road's edge now sits empty.

"I hate driving by there," says MacPherson, who passes the plant on a daily basis. "I just try not to look."

Origin

Source: Huff

No comments:

Post a Comment