In 2003, $350,000 bought Toronto resident Steven de Blois and his wife a house in the city’s colourful Cabbagetown neighbourhood. Eight years and two children later, the couple was looking to buy again. They settled on purchasing another home in the same neighbourhood -- this time for just under $1 million.

“We didn’t really see ourselves moving out. I saw myself in that [first] house forever,” 36-year-old de Blois says. “But there was an opportunity and we jumped on it.”

With the world economy in a state of flux, de Blois admits it perhaps wasn’t the most advisable option.

“I don’t enjoy taking on more debt,” he says. “You never know what tomorrow holds, but today my money is on Cabbagetown.”

For de Blois, a product manager for online and mobile channels married to a real estate agent, those million-dollar figures may not be too daunting when it comes to buying a stately Victorian home. But the numbers reflect a new reality in Toronto, as well as elsewhere throughout the Western world: The disappearance of the middle class.

Cabbagetown, once an eclectic mix of rich, poor and everything in between, is losing its middle class, and an ever-larger proportion of its population hails from either the top of the income ladder, or the bottom. It’s a phenomenon that is repeating across the city of Toronto -- and around the Western world, the seemingly inevitable result of a growing income gap.

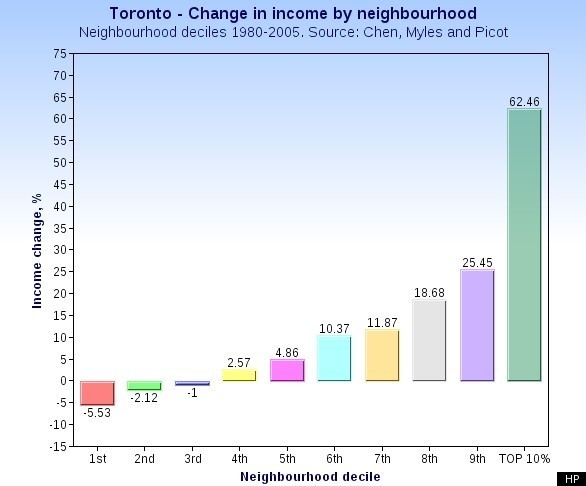

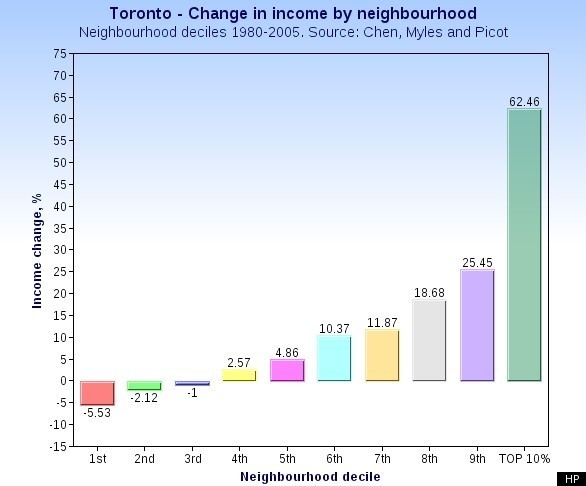

The mixed-income neighbourhoods that used to define Toronto are disappearing. Two-thirds of the city’s residents were in the middle-income bracket in 1970, compared to about one-third in 2000. According to one study, there will likely be more neighbourhoods with very high incomes than those in the middle by 2020.

Cabbagetown is one of the clearest examples of shrinking middle-class neighbourhoods in the city.

According to real estate agent Daniel Bloch, homes in the area now sell in a range between $750,000 and $1.4 million -- twice to four times the national average.

Yet Cabbagetown is not twice to four times as wealthy as the country as a whole.

In 2005, median household income in Toronto was $52,833. The median income by private household was $54,654 in Cabbagetown-South St. James Town -- nearly the same as the city as a whole.

However, of the 6,050 households in the neighbourhood, the largest group of households -- 1,325 or 22 per cent -- had incomes above $100,000. The second-largest group -- 830 or 17 per cent -- had incomes of $10,000 to $19,999. Of these households, slightly more than half made less than the city’s median income.

These numbers -- showing plenty of high-income earners, even more low-income earners and little in between -- suggest that Cabbagetown’s middle-class past is far behind it.

“The question of affordability has long been rendered moot because these houses aren’t affordable,” says Amy Lavender Harris, a geography teacher at York University. “How do you pay for a $700,000 house on a $50,000 income?”

Admittedly, the large differences in earnings and demographics are part of what make Cabbagetown the colourful neighbourhood that it is.

Cabbagetown’s residents often say they enjoy the mix of new and old the area offers. The neighbourhood boasts the largest continuous area of preserved Victorian housing in North America.

As a result, preservation work is a constant in Cabbagetown life.

“Obviously keeping the ambience of the neighbourhood as we see it today brings potential buyers into the neighbourhood, which helps the prices of homes stay as they are,” says David Pretlove, chair of the Cabbagetown Preservation Association.

The current trend in Cabbagetown can be traced back to the 1970s, when the area was a less-than-desirable part of town. Entrepreneurs began buying properties inexpensively and fixed them up, beginning a long process of gentrification.

At this point, Cabbagetown’s official boundaries were altered, leaving out a housing project on its southern borders -- a move some urban development experts say was a blatant attempt at social exclusion.

“When what we now know as Cabbagetown gentrified, there was a desire to separate itself from the housing project to the south,” Harris says. “Over a period of time the whole area south of Gerrard [Street] was actually erased from history as ever having been associated with Cabbagetown.”

In 2004, a large area of Cabbagetown was declared a heritage district. Heritage conservation designation means that when a property owner applies for a building permit, a secondary review with a focus on the streetscape of the building is required.

“It’s [a sort of] stature. I know homeowners take huge pride in that,” says Bloch. “It definitely does help the value.”

While heritage conservation is a positive undertaking at its core, the motivations behind it, at least in the case of Cabbagetown, are questionable.

“Neighbourhood preservation ... has become a problem because property values are basically the chief consideration that individual property owners make in deciding to go along with a proposal for heritage conservation. ‘Will it increase my property value?’" Harris says.

Cabbagetown is hardly an anomaly, and what’s happening there is telling of dissipating middle class communities throughout the Western world, Pretlove says.

“It plays out in a neighbourhood like this too," he says. "There were those in the middle who were able to aspire up in the last 40 to 50 years but it’s perhaps going to be a little more difficult for the new generation.”

Yet it may be too early to declare the demise of Toronto's middle class neighbourhoods. Just as Cabbagetown gentrified and eventually became an affluent neighbourhood, low-income areas may become home to middle-income residents as they redevelop.

Regent Park, the low-income neighbourhood cut out of Cabbagetown in the 1970s, is currently going through its own redevelopment. As the area dismantles, it will give way to dynamic change in that part of the city. The rebuilt Regent Park will include about 2,000 subsidized housing units and close to 3,000 condo units.

“The whole idea is to mix up the income levels,” says Pretlove. “Mix up the income levels and people can work it out and hopefully it will help rise up a certain sector of society.”

Such economic diversity should mean positive change for Regent Park and surrounding communities, including Cabbagetown.

“Would I want to live in a more homogeneous area? No, I don’t think so,” says de Blois. “I’m sure I’d be happy in other parts of the city but this is what is home now.”

De Blois and others like him have the good fortune of being able to pick and choose where in the city they would like to live. But as Cabbagetown shows, that freedom is becoming a luxury fewer and fewer can afford.

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Daniela Costa

“We didn’t really see ourselves moving out. I saw myself in that [first] house forever,” 36-year-old de Blois says. “But there was an opportunity and we jumped on it.”

With the world economy in a state of flux, de Blois admits it perhaps wasn’t the most advisable option.

“I don’t enjoy taking on more debt,” he says. “You never know what tomorrow holds, but today my money is on Cabbagetown.”

For de Blois, a product manager for online and mobile channels married to a real estate agent, those million-dollar figures may not be too daunting when it comes to buying a stately Victorian home. But the numbers reflect a new reality in Toronto, as well as elsewhere throughout the Western world: The disappearance of the middle class.

Cabbagetown, once an eclectic mix of rich, poor and everything in between, is losing its middle class, and an ever-larger proportion of its population hails from either the top of the income ladder, or the bottom. It’s a phenomenon that is repeating across the city of Toronto -- and around the Western world, the seemingly inevitable result of a growing income gap.

The mixed-income neighbourhoods that used to define Toronto are disappearing. Two-thirds of the city’s residents were in the middle-income bracket in 1970, compared to about one-third in 2000. According to one study, there will likely be more neighbourhoods with very high incomes than those in the middle by 2020.

Cabbagetown is one of the clearest examples of shrinking middle-class neighbourhoods in the city.

According to real estate agent Daniel Bloch, homes in the area now sell in a range between $750,000 and $1.4 million -- twice to four times the national average.

Yet Cabbagetown is not twice to four times as wealthy as the country as a whole.

In 2005, median household income in Toronto was $52,833. The median income by private household was $54,654 in Cabbagetown-South St. James Town -- nearly the same as the city as a whole.

However, of the 6,050 households in the neighbourhood, the largest group of households -- 1,325 or 22 per cent -- had incomes above $100,000. The second-largest group -- 830 or 17 per cent -- had incomes of $10,000 to $19,999. Of these households, slightly more than half made less than the city’s median income.

These numbers -- showing plenty of high-income earners, even more low-income earners and little in between -- suggest that Cabbagetown’s middle-class past is far behind it.

Carlton St. in Toronto's Cabbagetown, looking east to Parliament St. Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail

“The question of affordability has long been rendered moot because these houses aren’t affordable,” says Amy Lavender Harris, a geography teacher at York University. “How do you pay for a $700,000 house on a $50,000 income?”

Admittedly, the large differences in earnings and demographics are part of what make Cabbagetown the colourful neighbourhood that it is.

Cabbagetown’s residents often say they enjoy the mix of new and old the area offers. The neighbourhood boasts the largest continuous area of preserved Victorian housing in North America.

As a result, preservation work is a constant in Cabbagetown life.

“Obviously keeping the ambience of the neighbourhood as we see it today brings potential buyers into the neighbourhood, which helps the prices of homes stay as they are,” says David Pretlove, chair of the Cabbagetown Preservation Association.

The current trend in Cabbagetown can be traced back to the 1970s, when the area was a less-than-desirable part of town. Entrepreneurs began buying properties inexpensively and fixed them up, beginning a long process of gentrification.

At this point, Cabbagetown’s official boundaries were altered, leaving out a housing project on its southern borders -- a move some urban development experts say was a blatant attempt at social exclusion.

“When what we now know as Cabbagetown gentrified, there was a desire to separate itself from the housing project to the south,” Harris says. “Over a period of time the whole area south of Gerrard [Street] was actually erased from history as ever having been associated with Cabbagetown.”

In 2004, a large area of Cabbagetown was declared a heritage district. Heritage conservation designation means that when a property owner applies for a building permit, a secondary review with a focus on the streetscape of the building is required.

“It’s [a sort of] stature. I know homeowners take huge pride in that,” says Bloch. “It definitely does help the value.”

While heritage conservation is a positive undertaking at its core, the motivations behind it, at least in the case of Cabbagetown, are questionable.

“Neighbourhood preservation ... has become a problem because property values are basically the chief consideration that individual property owners make in deciding to go along with a proposal for heritage conservation. ‘Will it increase my property value?’" Harris says.

Cabbagetown is hardly an anomaly, and what’s happening there is telling of dissipating middle class communities throughout the Western world, Pretlove says.

“It plays out in a neighbourhood like this too," he says. "There were those in the middle who were able to aspire up in the last 40 to 50 years but it’s perhaps going to be a little more difficult for the new generation.”

Yet it may be too early to declare the demise of Toronto's middle class neighbourhoods. Just as Cabbagetown gentrified and eventually became an affluent neighbourhood, low-income areas may become home to middle-income residents as they redevelop.

Regent Park, the low-income neighbourhood cut out of Cabbagetown in the 1970s, is currently going through its own redevelopment. As the area dismantles, it will give way to dynamic change in that part of the city. The rebuilt Regent Park will include about 2,000 subsidized housing units and close to 3,000 condo units.

“The whole idea is to mix up the income levels,” says Pretlove. “Mix up the income levels and people can work it out and hopefully it will help rise up a certain sector of society.”

Such economic diversity should mean positive change for Regent Park and surrounding communities, including Cabbagetown.

“Would I want to live in a more homogeneous area? No, I don’t think so,” says de Blois. “I’m sure I’d be happy in other parts of the city but this is what is home now.”

De Blois and others like him have the good fortune of being able to pick and choose where in the city they would like to live. But as Cabbagetown shows, that freedom is becoming a luxury fewer and fewer can afford.

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Daniela Costa

No comments:

Post a Comment