As debate about Canada’s rich-poor divide intensifies, a new report highlights the growing income gap between top-paid CEOs and average Canadians.

According to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the 100 highest-earning CEOs on the TSX Index pocketed an average of $8.38 million in 2010 -- a 27 per cent increase over the previous year.

It’s a stark contrast to the annual incomes of average Canadians, whose wages, when adjusted for inflation, have actually been falling. By noon on January 3, the top paid CEOs will have already raked in an average $44,366 -- the amount that it took average workers an entire year to earn.

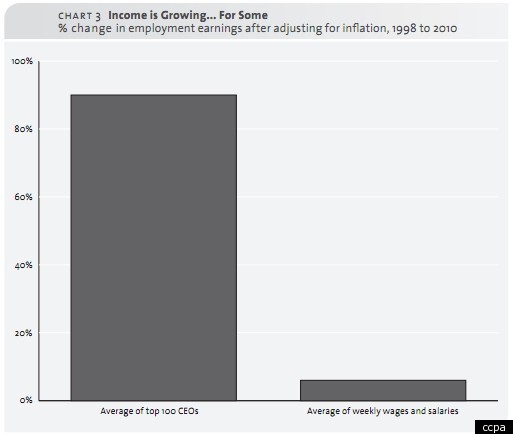

“There is obviously something very different at play here for CEO compensation compared with the compensation of other Canadians,” says CCPA economist and report author Hugh Mackenzie, noting that the substantial rise in CEO pay came during a period when average wages grew by just two per cent. “That’s a pretty big gulf in just one year.”

Deriding corporate compensation for executives as “a major driver of income inequality in Canada,” the report notes that top-paid CEOs banked 189 times the earnings of average Canadians in 2010, up from 105 in 1998.

Magna International Inc. founder Frank Stronach was by far the highest flying CEO in the group. In the year before he retired, Stronach pocketed more than $61.8 million -- thanks, in large part, to a $41 million bonus.

Fellow Magna execs Donald Walker and Siegfried Wolf snagged second and third spots, with earnings of $16.6 million and $16.5 million respectively.

At No. 85, Nancy Southern, president and CEO of Calgary-based Atco Group, was the only woman in the top 100, which includes bankers, resource producers and telecommunications giants.

The bump in CEO earnings in 2010 follows two years of relative flat-lining, as bonuses and the value of stock options -- important components of CEO compensation -- dipped during the economic downturn.

But according to Christopher Chen, a Toronto-based compensation consultant for the Hay Group, during the recession many corporate boards opted to make retention payments to CEOs, which “allowed them to keep sitting in the seats and doing what they were doing.”

“That really long fall from the top floor that we all expected to happen, it didn’t happen so much in 2008 and 2009,” he says. “For that reason, I can understand why people looking from the outside are fussed.”

The recovery has also been particularly been kind to CEOs, whose earnings came roaring back in 2010 as the market regained its footing.

“In 2009, in particular, stock options weren’t worth very much because the market was in such poor shape,” says Mackenzie. “But stock options became a very popular form of compensation again, partly because the stock market hit such low levels. When the stock market goes down, the potential upside from a stock option goes way up.”

Among the top 100 CEOs, the report found that 70 received part of their pay in grants of stock and 73 in stock options. The average grant was valued at $2.6 million; the average awarded options, meanwhile, were $3.2 million.

NOT-SO-FRINGE BENEFITS

CEOs also benefit from more generous retirement plans than Canadians typically enjoy.

Whereas 30 per cent of Canadians have defined-benefit pension plans, in 2010, nearly half of the top 100 CEO had this type of gold-plated plan, which had accrued to pay an average annual pension of $1.19 million upon retirement.

At the same time, a growing number of Canadians are finding themselves on defined-contribution plans, which do not guarantee any level of income for retirees.

Though CEO pay in Canada is much lower than in the United States, Mackenzie says the rate at which it is ballooning “puts a face on” deepening income inequality, which has ratcheted up substantially in recent decades.

“When you look around the rest of the industrialized world, Canada still stands out as generating excessive inequality,” says Mackenzie, noting the findings of a recent report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As the CCPA report notes, with earnings ranging from $3.9 million to $61 million, the top 100 CEOs are among the top 0.01 per cent of the income distribution -- which, in 2007, was a group of 2,460 tax filers with incomes of at least $1.85 million.

“Although its a pretty small percentage [of the total population], they are grabbing a non-trivial percentage of the national growth in income,” says Mackenzie. “Living in a world where the top of the top is detaching itself is not good for the way the economy works or the way society works.”

All of which, as far as Mackenzie is concerned, should be adequate motivation to rein in CEO pay.

The CCPA report argues CEO pay has gotten out of hand at least in part because boards often find themselves in a “prisoner’s dilemma” -- caught between the desire to cut costs and the need to remain competitive. In that context, government is “the only actor left to inject sanity into an irrational compensation sytem,” either through regulation or changes to the tax system, the report states.

Chen, however, sees the issue somewhat less starkly. In his view, there’s nothing wrong with “the level of pay provided to a CEO as long as the CEO produces results.”

Yet, when it comes to the link between pay and performance in major companies that the Hay Group has examined, he says, “The correlation is not as close as we’d like. We’d like it to be perfect. Well, it’s nowhere near perfect. We think it can drastically improve.”

Though Chen says he is doubtful that the kind of government intervention in executive compensation that has occurred in the U.K. and the Eurozone in recent years will gain traction in Canada, he says there is still opportunity for reform.

“The hope is that fuller disclosure of compensation will shine light on compensation practices, good or bad, and that in and of itself will raise attention, and change the way things are being done,” he says.

Original Article

Source: Huff

According to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the 100 highest-earning CEOs on the TSX Index pocketed an average of $8.38 million in 2010 -- a 27 per cent increase over the previous year.

It’s a stark contrast to the annual incomes of average Canadians, whose wages, when adjusted for inflation, have actually been falling. By noon on January 3, the top paid CEOs will have already raked in an average $44,366 -- the amount that it took average workers an entire year to earn.

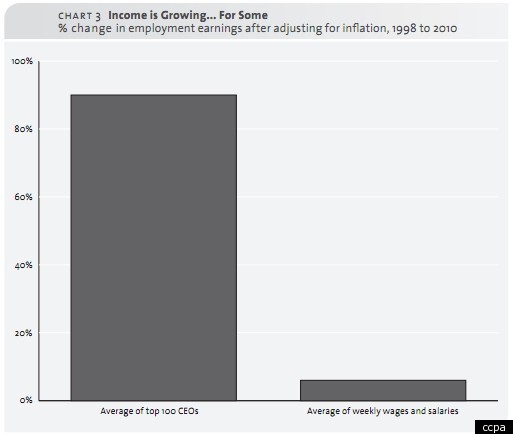

“There is obviously something very different at play here for CEO compensation compared with the compensation of other Canadians,” says CCPA economist and report author Hugh Mackenzie, noting that the substantial rise in CEO pay came during a period when average wages grew by just two per cent. “That’s a pretty big gulf in just one year.”

Deriding corporate compensation for executives as “a major driver of income inequality in Canada,” the report notes that top-paid CEOs banked 189 times the earnings of average Canadians in 2010, up from 105 in 1998.

Magna International Inc. founder Frank Stronach was by far the highest flying CEO in the group. In the year before he retired, Stronach pocketed more than $61.8 million -- thanks, in large part, to a $41 million bonus.

Fellow Magna execs Donald Walker and Siegfried Wolf snagged second and third spots, with earnings of $16.6 million and $16.5 million respectively.

At No. 85, Nancy Southern, president and CEO of Calgary-based Atco Group, was the only woman in the top 100, which includes bankers, resource producers and telecommunications giants.

The bump in CEO earnings in 2010 follows two years of relative flat-lining, as bonuses and the value of stock options -- important components of CEO compensation -- dipped during the economic downturn.

But according to Christopher Chen, a Toronto-based compensation consultant for the Hay Group, during the recession many corporate boards opted to make retention payments to CEOs, which “allowed them to keep sitting in the seats and doing what they were doing.”

“That really long fall from the top floor that we all expected to happen, it didn’t happen so much in 2008 and 2009,” he says. “For that reason, I can understand why people looking from the outside are fussed.”

The recovery has also been particularly been kind to CEOs, whose earnings came roaring back in 2010 as the market regained its footing.

“In 2009, in particular, stock options weren’t worth very much because the market was in such poor shape,” says Mackenzie. “But stock options became a very popular form of compensation again, partly because the stock market hit such low levels. When the stock market goes down, the potential upside from a stock option goes way up.”

Among the top 100 CEOs, the report found that 70 received part of their pay in grants of stock and 73 in stock options. The average grant was valued at $2.6 million; the average awarded options, meanwhile, were $3.2 million.

NOT-SO-FRINGE BENEFITS

CEOs also benefit from more generous retirement plans than Canadians typically enjoy.

Whereas 30 per cent of Canadians have defined-benefit pension plans, in 2010, nearly half of the top 100 CEO had this type of gold-plated plan, which had accrued to pay an average annual pension of $1.19 million upon retirement.

At the same time, a growing number of Canadians are finding themselves on defined-contribution plans, which do not guarantee any level of income for retirees.

Though CEO pay in Canada is much lower than in the United States, Mackenzie says the rate at which it is ballooning “puts a face on” deepening income inequality, which has ratcheted up substantially in recent decades.

“When you look around the rest of the industrialized world, Canada still stands out as generating excessive inequality,” says Mackenzie, noting the findings of a recent report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As the CCPA report notes, with earnings ranging from $3.9 million to $61 million, the top 100 CEOs are among the top 0.01 per cent of the income distribution -- which, in 2007, was a group of 2,460 tax filers with incomes of at least $1.85 million.

“Although its a pretty small percentage [of the total population], they are grabbing a non-trivial percentage of the national growth in income,” says Mackenzie. “Living in a world where the top of the top is detaching itself is not good for the way the economy works or the way society works.”

All of which, as far as Mackenzie is concerned, should be adequate motivation to rein in CEO pay.

The CCPA report argues CEO pay has gotten out of hand at least in part because boards often find themselves in a “prisoner’s dilemma” -- caught between the desire to cut costs and the need to remain competitive. In that context, government is “the only actor left to inject sanity into an irrational compensation sytem,” either through regulation or changes to the tax system, the report states.

Chen, however, sees the issue somewhat less starkly. In his view, there’s nothing wrong with “the level of pay provided to a CEO as long as the CEO produces results.”

Yet, when it comes to the link between pay and performance in major companies that the Hay Group has examined, he says, “The correlation is not as close as we’d like. We’d like it to be perfect. Well, it’s nowhere near perfect. We think it can drastically improve.”

Though Chen says he is doubtful that the kind of government intervention in executive compensation that has occurred in the U.K. and the Eurozone in recent years will gain traction in Canada, he says there is still opportunity for reform.

“The hope is that fuller disclosure of compensation will shine light on compensation practices, good or bad, and that in and of itself will raise attention, and change the way things are being done,” he says.

Original Article

Source: Huff

No comments:

Post a Comment