Canadian manufacturing sales may have rebounded to near pre-recession levels, but the same cannot be said of manufacturing employment.

Canadian manufacturing sales may have rebounded to near pre-recession levels, but the same cannot be said of manufacturing employment.New figures released by Statistics Canada on Thursday show that December marked the fifth increase in manufacturing sales in six months, with sales rising to $49.9 billion -- not far off the $50.2 billion logged in October 2008.

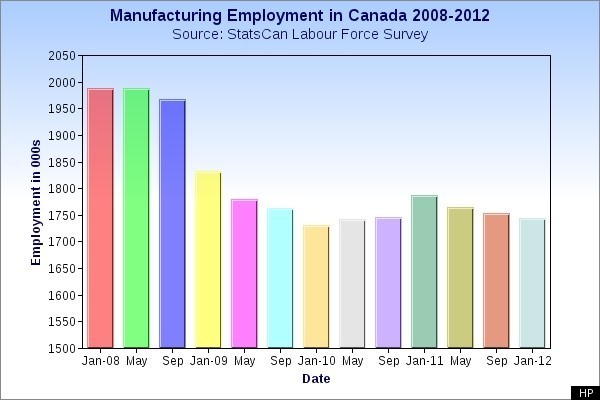

Manufacturing employment, however, shows little sign of bouncing back: over the same period, says Statscan analyst Vincent Ferrao, the sector posted a net loss of more than 200,000 jobs; in January, total manufacturing employment was 11 per cent lower than it was in the fall of 2008.

The relatively weak employment numbers highlight the legacy of a downturn that evaporated hundreds of thousands of jobs, and quickened the pace of a fundamental labour market shift.

Angelo DiCaro, a national communications representative for the Canadian Auto Workers’ union, characterizes the gap between the rebound in manufacturing sales and employment as “tremendous.”

“Any uptick in manufacturing sales is really not being seen or felt by the legion of laid off manufacturing workers across the country, that’s for sure,” he said.

In the aftermath of an economic shock, it’s common for employment levels to lag production as companies test the waters before expanding their ranks. But RBC economist Nathan Janzen concedes that the gap in this instance remains wider than expected.

“We were a little surprised. Given that the manufacturing recovery in Canada started really a couple of years ago, we should have already been seeing the manufacturing employment keeping up with production,” he told The Huffington Post.

It’s tough to know what, precisely, is behind the discrepancy, but the challenges that have long plagued Canadian manufacturing are no doubt partly to blame.

Even before the recession, the combination of a strong Canadian dollar, increasing automation and competition from cheap imports was taking a significant bite out of output and employment. Since 2002, DiCaro says the sector has shed nearly 600,000 jobs, over half of which were lost in Ontario, where manufacturing sales “are still below levels seen in the late ’90s and early 2000s.”

“We’ve seen such a collapse in manufacturing production that any uptick that we’re starting to see, we’re just nowhere near where we were,” he said. “When you start looking at the jobs, I don’t know if we’ll ever be where we were less than a decade ago.”

The downturn sped up the decline, with the bulk of the employment loss in the past decade occurring in 2008 and 2009 in Ontario’s once-robust auto industry hubs.

“A lot of that employment has been difficult to recover,” he said. “It’s difficult to say if those jobs will come back or not.”

As employment growth moves to other sectors, such as service and construction, DiCaro says the shift does not bode well for workers, who are often faced with lower wages, greater job insecurity and fewer employer benefits than traditional manufacturing jobs offered.

“We’re not trading off those job losses for equivalent jobs,” he said.

The recent uptick in manufacturing sales in December was concentrated in the transportation equipment industry, where sales rose by 3.7 per cent in December to $8.5 billion. Plastics and rubber products producers and primary metal manufacturers also posted sales gains, while a decline in prices pushed down the dollar value of sales for petroleum and coal product manufacturers.

But Ferrao suspects that a still-shaky global economic climate continues to make employers, who have become accustomed to doing more with less, hesitant to take on a significant number of new hires.

“In order to increase productivity, manufacturers would probably use less labour, or get the labour they have to work more hours,” Ferrao said, adding, “there’s not necessarily a correlation between sales and employment.”

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Rachel Mendleson

No comments:

Post a Comment