NEW YORK -- Military strikes expected! Weapons inspectors called in! A murky al Qaeda connection! And Cheney says time's up for Ira...

Wait. Haven't we seen this movie before?

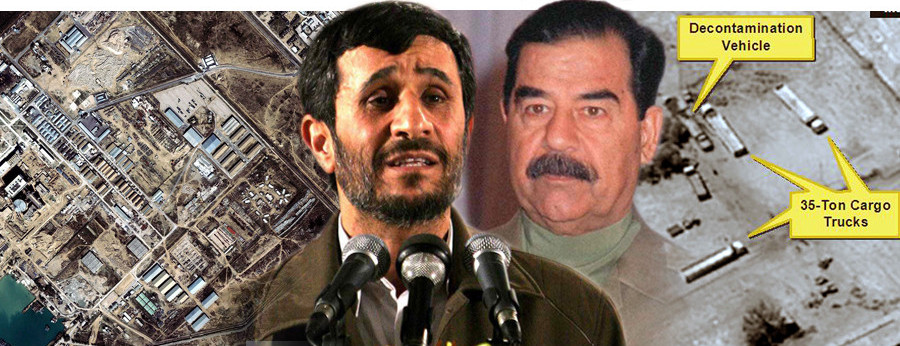

It's already been a decade since the media hyped bogus WMD claims prior to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. But it sure feels like 2002 for anyone who was around then and is now scanning newspaper headlines or watching TV talking-heads discuss a possible Israeli strike on Iran's nuclear facilities -- an act which could pull the U.S. into another thorny Middle East military conflict.

Some of the media's more overheated Iran coverage bears an eerie resemblance to Iraq coverage, but instead of former Vice President Dick Cheney we have his daughter Liz Cheney making the Sunday show rounds.

"A nuclear weapon in the hands of the world's worst sponsor of terror, one of them, is something we can't stand for," Cheney said Sunday on ABC's "This Week."

The Iran nuclear story has also led several network newscasts this week. On Tuesday, ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer talked of a "shadow war being waged by Iran," followed by chief investigative correspondent Brian Ross describing a "violent series of attacks by Iran," which may be retaliation for the recent killing of Iranian scientists.

CBS News anchor Scott Pelley kicked off Wednesday's broadcast by saying that Iran is "defying the world," while NBC's Brian Williams asked if "the U.S. about to get dragged into a new confrontation."

One national security reporter, who has covered the intelligence community and Iran but was not authorized to comment, says that pre-Iraq War coverage and recent Iran coverage are "terrifyingly similar."

"I don't think we are falling totally back into where we were before, but I do think you're seeing, in some corners of our profession, we're making the same mistakes we made a decade ago," the reporter said. "We're taking things at face value and we're rushing to get ahead of a story that we don't know where it's going."

While questions have loomed for years about Iran's nuclear intentions and ability to produce weapons-grade uranium, we're now in the midst of a full-scale flood of stories suggesting that Iran is on track to build a nuclear bomb, and even some speculating that the Iranian regime may strike the United States, perhaps in collusion with terrorists.

On Wednesday, British broadcaster Sky News -- citing intelligence officials -- claimed that Iran and al Qaeda "have established an operational relationship amid fears the terror group is planning a spectacular attack against the West." The Daily Telegraph, another British outlet, published a similar story attributing the link to what "officials believe."

National security and intelligence reporting often requires quoting anonymous officials, of course, and is subject to the same pitfalls that other source-centric beats face (like Wall Street dealmaking, for example). Even a piece on coverage of that coverage -- like this one -- includes one anonymous source. All of which begs a very germane question: To what extent is this community of foreign policy background sources spinning the media on Iran? And does the media really have any way of meaningfully assessing the merits of what those sources are saying?

Exhibit A from the pre-Iraq invasion days for why more caution may be in order: the false reports of a "Prague connection" between 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta and Iraqi officials -- a thinly-sourced story promoted in the media and seized upon by officials from the administration of former President George W. Bush.

Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a Holocaust denier, is an inviting target. He has long spoken about confronting Israel, and he routinely makes outrageous statements that commentators have seized upon to justify a preventive strike to disrupt Iran's nuclear program.

"I cannot imagine the Israelis are going to allow Iran to go nuclear and to hold the Damocles sword over 6 million Jews all over again," columnist Charles Krauthammer said last week on Fox News. "Israel was established to prevent a second Holocaust, not to invite one."

The idea that Iran is currently in pursuit of -- or even already has -- a nuclear bomb has become accepted wisdom in much of Washington and amplified by the media. But the reality is much more opaque. When James Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, appeared before the Senate last month, he told lawmakers that "we don't believe they've actually made the decision to go ahead with a nuclear weapon." Clapper's statement reflected the conclusions of some in the intelligence community that Iran suspended its nuclear warhead program in 2003.

Both the latest U.S. assessments, and the most recent report of the International Atomic Energy Agency, which actively monitors the sites of Iran's nuclear energy program, buttress this viewpoint: While there is ample reason to fear Iran might acquire a nuclear weapon, and is capable of doing so, there is no definitive proof that they have yet decided to try.

The November IAEA report itself, initially touted as offering the first "credible" evidence of a nuclear weapons project, later turned out to be a far weaker document, offering allegations that The New York Times described as "not substantially new, and [which] have been discussed by experts for years." Arthur Brisbane, the Times' public editor, later took the paper to task for overstating the conclusiveness of the IAEA's findings.

Perhaps as a consequence of the murkiness of these assessments, public misinformation about Iran's nuclear project remains exceedingly high: in a 2010 poll, 7 in 10 Americans said they believe Iran already has the weapons. (In the Iraq War's early days, 81 percent of Americans said they believed the country likely possessed WMD's, an understandable conclusion given Bush administration statements and the media's coverage).

There's an important difference between then and now, though, even if the media drumbeat sounds familiar. The current White House isn't in a rush to go to war.

Blake Hounshell, managing editor of Foreign Policy magazine, says "the major difference is that the [Obama] administration is not orchestrating this the way the Bush administration was in driving selective leaks of intelligence."

Several other journalists, in interviews with The Huffington Post, pointed out that the Obama administration appears intent on seeing if sanctions work and finding a diplomatic solution to Iran's nuclear ambitions, especially after over 10 years of conflict following the attacks of Sept. 11.

In 2002, Bush administration officials raised the specter of mushroom clouds on Sunday morning shows if the U.S didn't act and the White House press secretary openly encouraged Iraqi citizens to assassinate Saddam Hussein. In contrast, the Obama administration has been relatively cautious in its statements about Iran. But to be sure, the White House doesn't have to be any more aggressive when Israeli officials, in conversations with reporters, are always ready to dial up the threat or play down the consequences of a strike.

"I don't think it's anything like the Iraq war," said Newsweek's Eli Lake, who co-wrote the magazine's in-depth story this week on the "dangerous game" playing out between Israel, Iran and the United States. "The most aggressive actor is another country, not America." The question now, Lake said, is, "will Israel bomb Iran because they don't expect Obama will take the action if the sanctions don't work?"

"The Obama administration," Lake added, "takes great pains to say their policy isn't regime change,"

That's why Iran-watchers took note when the Washington Post published an explosive claim online last month by an anonymous "senior U.S. official" that the goal of Iranian sanctions is regime collapse. But the Post soon scrubbed the claim about regime change for the next day's print edition. (Reporter Karen DeYoung told The Huffington Post that the initial story was based off handwritten notes, which she found to have misquoted the source when later listening to a recording of the interview.)

The U.S. military isn't enthusiastic about the military option, either. The Huffington Post's David Wood reported Wednesday on the military's concerns about getting dragged into a "war many believe would be messy, bloody, unpredictable and ultimately inconclusive."

"I think it's a different kind of media frenzy because it's not one that the Obama administration necessarily wants to have," Foreign Policy's Hounshell added. "The Israelis want to have it and the Israelis want the coverage to be more aggressive. The thing we don't really know is how serious the Israelis are [about striking Iran]."

But some have their suspicions. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta "believes there is a strong likelihood that Israel will strike Iran in April, May or June," according to a much-discussed Feb. 2 column by the Washington Post's David Ignatius. When asked about the uptick in recent Iran coverage, Ignatius told The Huffington Post it's appropriate for there to be a "growing discussion of the danger of military confrontation."

"I think the thing I have learned from the experience of 2003 is that it's important to raise questions of whether a military attack makes sense," Ignatius said, "and to try to pull from U.S. government officials information that challenges the assumption that a military attack would be easy, would deliver the intended result." (While U.S officials are unlikely to say the military option would be easy, Israeli officials have suggested to journalists that Iran is "bluffing" about retaliating).

"It's important for there to be an open discussion of whether this makes sense," Ignatius added, "even if that seems to be, at times, hyping or overdramatizing the possibility of war."

New York Times reporter David Sanger, who has written extensively on Iran and nuclear issues, said that he's "discovered that even the most scrupulously neutral story prompts emails from some readers who argue, in essence, that by writing about the subject we are somehow encouraging an attack on Iran."

"I reject that view -- after all, simply because we write about atrocities in Syria or nuclear tests in North Korea does not mean we are prescribing American military action," Sanger continued. "My job is not to advocate an approach -- it is to make sure we explore and explain each option, and its pros and cons. And in Iran's case there are many alternatives to military action -- diplomacy, sanctions, covert action. We have written extensively about each of them, and noted that in the eyes of some experts, each may buy more time than a military attack."

Some reporters have done admirable work in describing the complexity of the situation in Iran and how it's different from Iraq -- even if on the surface, the frenzy looks remarkably similar. Even so, there have been plenty of reports that appear to be hyping Iranian threats rather than proceeding more cautiously, including scary headlines that get shot down later in the same article the headline touts.

For example, the Wall Street Journal recently reported that "U.S. officials say they believe Iran recently gave new freedoms to as many as five top al Qaeda operatives who have been under house arrest." But following several qualifiers around sourcing -- like "say they believe" or "may have provided" -- the Journal later quoted a U.S. official saying the following: "There is not significant information to suggest a working relationship between Iran and al Qaeda."

Three days earlier, Foreign Affairs reported that "virtually unnoticed, since late 2001, Iran has held some of al Qaeda's most senior leaders." The Foreign Affairs lead suggests a hidden Iran-al Qaeda connection, and the headline on the piece is even more blunt about it: "Al Qaeda in Iran: Why Tehran is Accommodating the Terrorist Group."

As a counterpoint to this perspective, the Associated Press published a deeply reported investigation two years ago on the "enduring mystery of al Qaeda leaders and operatives who fled into Iran after 9/11 and have been detained there for years."

The AP reported that some al Qaeda's leaders had moved around Iran, or even left the country, while cautioning that "intelligence officials don't fully understand" the, at times, fractious relationship between the Sunni terror group and Shiite regime. "Monitoring and understanding al Qaeda in Iran remains one of the most difficult jobs in U.S. intelligence," the AP reported.

It's not only the Iran-al Qaeda connection that's led to hawkish headlines. On Jan. 31, the Washington Post ran this ominous headline: "Iran, perceiving threat from West, willing to attack on U.S. soil, U.S. intelligence report finds." Several paragraphs into the story, however, the Post notes that "U.S. officials said they have seen no intelligence to indicate that Iran is actively plotting attacks on U.S. soil." The headline-grabbing assessment appears to stem solely from an allegedly Iranian-linked plot to assassinate Saudi Arabia's ambassador in Washington D.C. that was foiled in October. The bungled scheme, and what it could indicate, was back in the news because National Intelligence Director Clapper discussed it -- among various other national security issues -- in Congressional testimony. But it's the Iran threat that got the most attention.

Salon's Glenn Greenwald, who has written extensively on U.S. media coverage of Iran in recent weeks, described the Post story as a "monument to mindless stenographic journalism" and -- along with a Foreign Affairs piece on an al Qaeda-Iran connection -- as part of "a concerted media-aided fear-mongering campaign aimed at Iran."

"So, to recap: Iran is working closely with al Qaeda and is ready to launch Terrorist attacks inside the U.S.," Greenwald wrote. "Is it that hard to come up with new propaganda? Is recycling scary storylines really the best that can be done?"

When reached, Post national security reporter Greg Miller said the story speaks for itself.

NBC investigative correspondent Michael Isikoff, who co-authored "Hubris," a 2006 book on the selling of the Iraq War, said that "it's unfortunate that the experience in Iraq has so colored the debate on Iran, as to perhaps make it more difficult to focus on what the real issues are."

"People who are skeptical about claims about an Iranian nuclear program will point to the Iraq experience," Isikoff added. "That doesn't mean they're right and it doesn't mean they're wrong. It just means, it's just a historical fact that we're going to look at these issues through the lens of the misleading claims that were made about Iraq."

The Huffington Post's Joshua Hersh contributed reporting.

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Michael Calderone

Wait. Haven't we seen this movie before?

It's already been a decade since the media hyped bogus WMD claims prior to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. But it sure feels like 2002 for anyone who was around then and is now scanning newspaper headlines or watching TV talking-heads discuss a possible Israeli strike on Iran's nuclear facilities -- an act which could pull the U.S. into another thorny Middle East military conflict.

Some of the media's more overheated Iran coverage bears an eerie resemblance to Iraq coverage, but instead of former Vice President Dick Cheney we have his daughter Liz Cheney making the Sunday show rounds.

"A nuclear weapon in the hands of the world's worst sponsor of terror, one of them, is something we can't stand for," Cheney said Sunday on ABC's "This Week."

The Iran nuclear story has also led several network newscasts this week. On Tuesday, ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer talked of a "shadow war being waged by Iran," followed by chief investigative correspondent Brian Ross describing a "violent series of attacks by Iran," which may be retaliation for the recent killing of Iranian scientists.

CBS News anchor Scott Pelley kicked off Wednesday's broadcast by saying that Iran is "defying the world," while NBC's Brian Williams asked if "the U.S. about to get dragged into a new confrontation."

One national security reporter, who has covered the intelligence community and Iran but was not authorized to comment, says that pre-Iraq War coverage and recent Iran coverage are "terrifyingly similar."

"I don't think we are falling totally back into where we were before, but I do think you're seeing, in some corners of our profession, we're making the same mistakes we made a decade ago," the reporter said. "We're taking things at face value and we're rushing to get ahead of a story that we don't know where it's going."

While questions have loomed for years about Iran's nuclear intentions and ability to produce weapons-grade uranium, we're now in the midst of a full-scale flood of stories suggesting that Iran is on track to build a nuclear bomb, and even some speculating that the Iranian regime may strike the United States, perhaps in collusion with terrorists.

On Wednesday, British broadcaster Sky News -- citing intelligence officials -- claimed that Iran and al Qaeda "have established an operational relationship amid fears the terror group is planning a spectacular attack against the West." The Daily Telegraph, another British outlet, published a similar story attributing the link to what "officials believe."

National security and intelligence reporting often requires quoting anonymous officials, of course, and is subject to the same pitfalls that other source-centric beats face (like Wall Street dealmaking, for example). Even a piece on coverage of that coverage -- like this one -- includes one anonymous source. All of which begs a very germane question: To what extent is this community of foreign policy background sources spinning the media on Iran? And does the media really have any way of meaningfully assessing the merits of what those sources are saying?

Exhibit A from the pre-Iraq invasion days for why more caution may be in order: the false reports of a "Prague connection" between 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta and Iraqi officials -- a thinly-sourced story promoted in the media and seized upon by officials from the administration of former President George W. Bush.

Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a Holocaust denier, is an inviting target. He has long spoken about confronting Israel, and he routinely makes outrageous statements that commentators have seized upon to justify a preventive strike to disrupt Iran's nuclear program.

"I cannot imagine the Israelis are going to allow Iran to go nuclear and to hold the Damocles sword over 6 million Jews all over again," columnist Charles Krauthammer said last week on Fox News. "Israel was established to prevent a second Holocaust, not to invite one."

The idea that Iran is currently in pursuit of -- or even already has -- a nuclear bomb has become accepted wisdom in much of Washington and amplified by the media. But the reality is much more opaque. When James Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, appeared before the Senate last month, he told lawmakers that "we don't believe they've actually made the decision to go ahead with a nuclear weapon." Clapper's statement reflected the conclusions of some in the intelligence community that Iran suspended its nuclear warhead program in 2003.

Both the latest U.S. assessments, and the most recent report of the International Atomic Energy Agency, which actively monitors the sites of Iran's nuclear energy program, buttress this viewpoint: While there is ample reason to fear Iran might acquire a nuclear weapon, and is capable of doing so, there is no definitive proof that they have yet decided to try.

The November IAEA report itself, initially touted as offering the first "credible" evidence of a nuclear weapons project, later turned out to be a far weaker document, offering allegations that The New York Times described as "not substantially new, and [which] have been discussed by experts for years." Arthur Brisbane, the Times' public editor, later took the paper to task for overstating the conclusiveness of the IAEA's findings.

Perhaps as a consequence of the murkiness of these assessments, public misinformation about Iran's nuclear project remains exceedingly high: in a 2010 poll, 7 in 10 Americans said they believe Iran already has the weapons. (In the Iraq War's early days, 81 percent of Americans said they believed the country likely possessed WMD's, an understandable conclusion given Bush administration statements and the media's coverage).

There's an important difference between then and now, though, even if the media drumbeat sounds familiar. The current White House isn't in a rush to go to war.

Blake Hounshell, managing editor of Foreign Policy magazine, says "the major difference is that the [Obama] administration is not orchestrating this the way the Bush administration was in driving selective leaks of intelligence."

Several other journalists, in interviews with The Huffington Post, pointed out that the Obama administration appears intent on seeing if sanctions work and finding a diplomatic solution to Iran's nuclear ambitions, especially after over 10 years of conflict following the attacks of Sept. 11.

In 2002, Bush administration officials raised the specter of mushroom clouds on Sunday morning shows if the U.S didn't act and the White House press secretary openly encouraged Iraqi citizens to assassinate Saddam Hussein. In contrast, the Obama administration has been relatively cautious in its statements about Iran. But to be sure, the White House doesn't have to be any more aggressive when Israeli officials, in conversations with reporters, are always ready to dial up the threat or play down the consequences of a strike.

"I don't think it's anything like the Iraq war," said Newsweek's Eli Lake, who co-wrote the magazine's in-depth story this week on the "dangerous game" playing out between Israel, Iran and the United States. "The most aggressive actor is another country, not America." The question now, Lake said, is, "will Israel bomb Iran because they don't expect Obama will take the action if the sanctions don't work?"

"The Obama administration," Lake added, "takes great pains to say their policy isn't regime change,"

That's why Iran-watchers took note when the Washington Post published an explosive claim online last month by an anonymous "senior U.S. official" that the goal of Iranian sanctions is regime collapse. But the Post soon scrubbed the claim about regime change for the next day's print edition. (Reporter Karen DeYoung told The Huffington Post that the initial story was based off handwritten notes, which she found to have misquoted the source when later listening to a recording of the interview.)

The U.S. military isn't enthusiastic about the military option, either. The Huffington Post's David Wood reported Wednesday on the military's concerns about getting dragged into a "war many believe would be messy, bloody, unpredictable and ultimately inconclusive."

"I think it's a different kind of media frenzy because it's not one that the Obama administration necessarily wants to have," Foreign Policy's Hounshell added. "The Israelis want to have it and the Israelis want the coverage to be more aggressive. The thing we don't really know is how serious the Israelis are [about striking Iran]."

But some have their suspicions. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta "believes there is a strong likelihood that Israel will strike Iran in April, May or June," according to a much-discussed Feb. 2 column by the Washington Post's David Ignatius. When asked about the uptick in recent Iran coverage, Ignatius told The Huffington Post it's appropriate for there to be a "growing discussion of the danger of military confrontation."

"I think the thing I have learned from the experience of 2003 is that it's important to raise questions of whether a military attack makes sense," Ignatius said, "and to try to pull from U.S. government officials information that challenges the assumption that a military attack would be easy, would deliver the intended result." (While U.S officials are unlikely to say the military option would be easy, Israeli officials have suggested to journalists that Iran is "bluffing" about retaliating).

"It's important for there to be an open discussion of whether this makes sense," Ignatius added, "even if that seems to be, at times, hyping or overdramatizing the possibility of war."

New York Times reporter David Sanger, who has written extensively on Iran and nuclear issues, said that he's "discovered that even the most scrupulously neutral story prompts emails from some readers who argue, in essence, that by writing about the subject we are somehow encouraging an attack on Iran."

"I reject that view -- after all, simply because we write about atrocities in Syria or nuclear tests in North Korea does not mean we are prescribing American military action," Sanger continued. "My job is not to advocate an approach -- it is to make sure we explore and explain each option, and its pros and cons. And in Iran's case there are many alternatives to military action -- diplomacy, sanctions, covert action. We have written extensively about each of them, and noted that in the eyes of some experts, each may buy more time than a military attack."

Some reporters have done admirable work in describing the complexity of the situation in Iran and how it's different from Iraq -- even if on the surface, the frenzy looks remarkably similar. Even so, there have been plenty of reports that appear to be hyping Iranian threats rather than proceeding more cautiously, including scary headlines that get shot down later in the same article the headline touts.

For example, the Wall Street Journal recently reported that "U.S. officials say they believe Iran recently gave new freedoms to as many as five top al Qaeda operatives who have been under house arrest." But following several qualifiers around sourcing -- like "say they believe" or "may have provided" -- the Journal later quoted a U.S. official saying the following: "There is not significant information to suggest a working relationship between Iran and al Qaeda."

Three days earlier, Foreign Affairs reported that "virtually unnoticed, since late 2001, Iran has held some of al Qaeda's most senior leaders." The Foreign Affairs lead suggests a hidden Iran-al Qaeda connection, and the headline on the piece is even more blunt about it: "Al Qaeda in Iran: Why Tehran is Accommodating the Terrorist Group."

As a counterpoint to this perspective, the Associated Press published a deeply reported investigation two years ago on the "enduring mystery of al Qaeda leaders and operatives who fled into Iran after 9/11 and have been detained there for years."

The AP reported that some al Qaeda's leaders had moved around Iran, or even left the country, while cautioning that "intelligence officials don't fully understand" the, at times, fractious relationship between the Sunni terror group and Shiite regime. "Monitoring and understanding al Qaeda in Iran remains one of the most difficult jobs in U.S. intelligence," the AP reported.

It's not only the Iran-al Qaeda connection that's led to hawkish headlines. On Jan. 31, the Washington Post ran this ominous headline: "Iran, perceiving threat from West, willing to attack on U.S. soil, U.S. intelligence report finds." Several paragraphs into the story, however, the Post notes that "U.S. officials said they have seen no intelligence to indicate that Iran is actively plotting attacks on U.S. soil." The headline-grabbing assessment appears to stem solely from an allegedly Iranian-linked plot to assassinate Saudi Arabia's ambassador in Washington D.C. that was foiled in October. The bungled scheme, and what it could indicate, was back in the news because National Intelligence Director Clapper discussed it -- among various other national security issues -- in Congressional testimony. But it's the Iran threat that got the most attention.

Salon's Glenn Greenwald, who has written extensively on U.S. media coverage of Iran in recent weeks, described the Post story as a "monument to mindless stenographic journalism" and -- along with a Foreign Affairs piece on an al Qaeda-Iran connection -- as part of "a concerted media-aided fear-mongering campaign aimed at Iran."

"So, to recap: Iran is working closely with al Qaeda and is ready to launch Terrorist attacks inside the U.S.," Greenwald wrote. "Is it that hard to come up with new propaganda? Is recycling scary storylines really the best that can be done?"

When reached, Post national security reporter Greg Miller said the story speaks for itself.

NBC investigative correspondent Michael Isikoff, who co-authored "Hubris," a 2006 book on the selling of the Iraq War, said that "it's unfortunate that the experience in Iraq has so colored the debate on Iran, as to perhaps make it more difficult to focus on what the real issues are."

"People who are skeptical about claims about an Iranian nuclear program will point to the Iraq experience," Isikoff added. "That doesn't mean they're right and it doesn't mean they're wrong. It just means, it's just a historical fact that we're going to look at these issues through the lens of the misleading claims that were made about Iraq."

The Huffington Post's Joshua Hersh contributed reporting.

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Michael Calderone

No comments:

Post a Comment