On a biting, brittle mid-February morning 30 miles north of Detroit, Rick Santorum plants his flag in a patch of turf as politically fertile as exists in these United States. For three decades, Macomb County, Michigan, has been both a bellwether and a battleground, as its fabled Reagan Democrats first abandoned the party of Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, and Mike Dukakis, then gradually drifted back in support of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and Barack Obama. Today in Macomb, the action is as much on the Republican as the Democratic side, with the county GOP riven by a split between mainstream and tea-party cadres. And yet in demographic terms, Macomb remains Macomb: overwhelmingly white and mostly non-college-educated, heavily Catholic and staunchly socially conservative, economically anti-globalist and culturally anti-swell.

All of which is to say that when Santorum takes the podium to address a Michigan Faith & Freedom Coalition rally in Shelby Charter Township, the 1,500 souls he sees before him are his kind of people—and soon enough he is speaking their language. To explain how America has always differed from other nations, Santorum invokes the Almighty: “We believe … we are children of a loving God.” To elucidate the evils of Obamacare, Dodd-Frank, and cap-and-trade, he inveighs against liberal elites: “They want to control you, because like the kings of old, they believe they know better than you.” To highlight what’s at stake in 2012, he unfurls a grand (and entirely farkakte) historical flourish: “This decision will be starker than at any time since the election of 1860”—you know, the one featuring Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas on the eve of the Civil War.

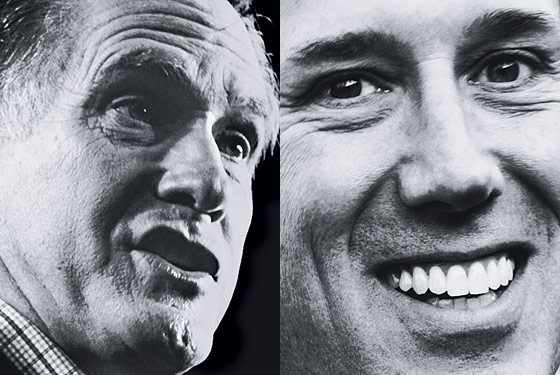

But before the nation faces that decision, Michigan has its own to make: between him and Mitt Romney in the Republican primary that takes place on February 28. “Do you want somebody who can go up against Barack Obama, take him on on the big issues … or do you want someone who can just manage Washington a little bit better?” Santorum asks, as the audience rises cheering to its feet. “That’s your choice. What does Michigan have to say?”

What Michiganders are telling pollsters is that their affections are split evenly between the two men, despite Romney’s status as the scion of one of the Wolverine State’s great political families. In Ohio, arguably the most important of ten states with primaries or caucuses on Super Tuesday, March 6, two recent surveys found Santorum holding a wide lead there, and the Gallup national tracking poll put him ahead of Romney by eight points as of February 24. Taken together, all this more than makes clear that Santorum has emerged as the dominant conservative alternative to Romney. It illustrates a shift in momentum so pronounced that, unless Romney takes Michigan and fares strongly on Super Tuesday, his ascension to his party’s nomination will be in serious jeopardy, as the calls for a late-entering white-knight candidate escalate—and odds of an up-for-grabs Republican convention rise. “Right now, I’d say they’re one in five,” says one of the GOP’s grandest grandees. “If Romney doesn’t put this thing away by Super Tuesday, I’d say they’re closer to 50-50.”

That Mitt Romney finds himself so imperiled by Rick Santorum—Rick Santorum!—is just the latest in a series of jaw-dropping developments in what has been the most volatile, unpredictable, and just plain wackadoodle Republican-nomination contest ever. Part of the explanation lies in Romney’s lameness as a candidate, in Santorum’s strength, and in the sudden efflorescence of social issues in what was supposed to be an all-economy-all-the-time affair. But even more important have been the seismic changes within the Republican Party. “Compared to 2008, all the candidates are way to the right of John McCain,” says longtime conservative activist Jeff Bell. “The fact that Romney is running with basically the same views as then but is seen as too moderate tells you that the base has moved rightward and doesn’t simply want a conservative candidate—it wants a very conservative one.”

The transfiguration of the GOP isn’t only about ideology, however. It is also about demography and temperament, as the party has grown whiter, less well schooled, more blue-collar, and more hair-curlingly populist. The result has been a party divided along the lines of culture and class: Establishment versus grassroots, secular versus religious, upscale versus downscale, highfalutin versus hoi polloi. And with those divisions have arisen the competing electoral coalitions—shirts versus skins, regulars versus red-hots—represented by Romney and Santorum, which are now increasingly likely to duke it out all spring.

Few Republicans greet that prospect sanguinely, though some argue that it will do little to hamper the party’s capacity to defeat Obama in the fall. “It’s reminiscent of the contest between Obama and Clinton,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell recently opined. “[That] didn’t seem to have done [Democrats] any harm in the general election, and I don’t think this contest is going to do us any harm, either.”

Yet the Democratic tussle in 2008, which featured two undisputed heavyweights with few ideological discrepancies between them, may be an exception that proves the rule. Certainly Republican history suggests as much: Think of 1964 and the scrap between the forces aligned with Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller, or 1976, between backers of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan. On both occasions, the result was identical: a party disunited, a nominee debilitated, a general election down the crapper.

With such precedents in mind, many Republicans are already looking past 2012. If either Romney or Santorum gains the nomination and then falls before Obama, flubbing an election that just months ago seemed eminently winnable, it will unleash a GOP apocalypse on November 7—followed by an epic struggle between the regulars and red-hots to refashion the party. And make no mistake: A loss is what the GOP’s political class now expects. “Six months before this thing got going, every Republican I know was saying, ‘We’re gonna win, we’re gonna beat Obama,’ ” says former Reagan strategist Ed Rollins. “Now even those who’ve endorsed Romney say, ‘My God, what a fucking mess.’ ”

Should Romney ultimately fail to become the Republican standard-bearer, history will record with precision the day the wheels came off the wagon—January 19. Until that morning, his march to the nomination was proceeding even more smoothly than he and his advisers had hoped. The apparent eight-vote win in Iowa. The landslide in New Hampshire. And then the double-digit leads in South Carolina polling, positioning him to pull off a historic early-state trifecta. But in the space of a few hours, Romney was serially (and surreally) battered by unwelcome events: three tracking polls putting him behind Gingrich for the first time in 2012; word from Iowa that his victory there was being snatched away and handed to Santorum; Rick Perry’s exit from the race and endorsement of Gingrich; and Newt’s masterly mau-mauing of CNN’s John King at a debate in Charleston over a (foolish, inartful, walking-blithely-into-a-buzzsaw) question about accusations by Gingrich’s second wife that he’d sought an “open marriage.”

By the next morning, it was evident that Romney was on his way to defeat in South Carolina, though few would have forecast the scale of the drubbing to come. In truth, any expectations Romney would win there were always overblown. His long-standing weakness with Evangelical voters was always likely to make him a hard sell to an electorate in which nearly two thirds self-identify as born-again. And that, in turn, led Team Romney to devote few resources to the state. “They had no real structure in South Carolina—none, nada,” says Jon Huntsman’s former chief strategist, John Weaver. “They ended up with a few figurehead endorsements and some late hires, but they had nothing on the ground.”

But South Carolina also laid bare weaknesses in Romney’s candidacy, some already well known, others brand spanking new—and devastating to the core rationale behind his campaign. All through 2011, Romney had focused laserlike on the economy, arguing that his private-sector background made him best suited to tackle Obama on the election’s central issue. Sure, Romney inspired little passion in the Republican base; but his rivals were clueless, cartoonish, or crackers, and with the GOP intent above all on ousting the incumbent, the presumption was that Romney’s combination of experience and presidential bearing would conquer all. “The Romney folks faced a fork in the road between the electable route and the ideological route,” says the manager of a previous Republican presidential campaign. “And they decided to go all-in on electability.”

Romney and his people never expected, however, to be confronted in the Republican phase of the race with a raft of challenges related to the legitimacy of his wealth. But first on his record at Bain Capital and then on his tax returns, that is what occurred. With Gingrich and Perry sounding more like commenters on Daily Kos than Republicans, Romney coughed up a remarkable collection of gaffes: from his fear of pink slips to his enjoyment of firing people to his “not very much” in speaker’s fees (when they totaled $374,327 last year).

For many Republicans, Romney’s maladroitness in addressing the issues at hand was worrisome, to put it mildly. Here he was handing Obama’s people a blooper reel that would let them paint him as a hybrid of Gordon Gekko and Thurston Howell III. “Republicans were saying, ‘This is the guy who’s gonna be carrying the ball for our side, defending the private sector?’ ” Rollins says incredulously. “Warren Buffett would kick his ass in a debate, let alone Obama.”

Nor were Romney’s rehearsed turns on the hustings appreciably better. From Iowa through New Hampshire, his campaign events had been progressively pared back and whittled down. By the time he reached South Carolina, they had achieved a certain purity—the purity of the null set. The climactic moment in them came when Romney would recite (and offer attendant textual analysis that would make Stanley Fish beat his head against a wall) the lyrics of “America the Beautiful.” Even staunch Romney allies were abashed by this sadly persistent, and persistently sad, rhetorical trope. “I have never seen anything more ridiculous or belittling,” a prominent Romney fund-raiser says.

Gingrich, by contrast, was on fire in South Carolina, and not just at the debates. His final event on the night before the primary, a rally aboard the USS Yorktown aircraft carrier in Charleston Harbor, included an encounter with a heckler who shouted out, “When will you release your ethics report?”—from a congressional investigation of Gingrich in the nineties.

Gingrich replied with a spontaneity and forcefulness as foreign to Romney as Urdu. “Actually, if you’d do a little research instead of shouting mindlessly, you’d discover the entire thing is available online in the Thomas system”—the online congressional database Gingrich brought into existence as Speaker of the House in 1995—“and you can print it out,” he fired back. “I think it is 900 pages. When you get done reading it, let me know if there are any questions.” The crowd cheered loudly and then Gingrich delivered the coup de grâce: “I assume you’re for the candidate who’s afraid to release his income taxes.”

But Gingrich wasn’t merely a superior performer to Romney on the stump. With his hot-eyed imprecations against Obama, his race-freighted mugging of Fox News’s Juan Williams at the debate in Myrtle Beach, his unbridled (if theatrical and hypocritical) enmity toward the media and East Coast elites more broadly, and his relentless ideological attacks on his rival as a timid “Massachusetts moderate,” he was far more deeply in sync with the raging id of the party’s ascendant populist wing.

The coalescence of the various elements of that wing around Gingrich accounted for the 40 to 28 percent pistol-whipping he administered to Romney on Primary Day—and marked the sharpening of the shirts-skins schism that would play out from then on. According to the exit polls, Gingrich captured 45 percent (to Romney’s 21) of Evangelical voters, 48 percent (to 21) of strong tea-party supporters, and 47 percent (to 22) of non–college graduates. Romney, meanwhile, held his own with the groups making up what the journalist Ron Brownstein has dubbed the GOP’s “managerial wing”—richer, better-educated, less godly, more pragmatic voters. One trouble for Romney was that this assemblage constitutes less than half his party now. But even more disconcerting was that he lost badly to Gingrich among South Carolinians who said that the most crucial candidate quality was the ability to beat Obama—which suggested not simply that ideology trumped electability but that for many Republicans, hard-core conservative ideology was tantamount to electability.

Thus did Romney find himself facing his first existential peril. The influential conservative blogger Erik Erickson, on the grounds that South Carolina represented less an embrace of Gingrich than a grassroots rejection of the front-runner, his themeless pudding of a campaign, and the Establishment support of it, encouraged Romney to “refine his message, not sharpen his knives” as the race moved to Florida. But that suggestion would be rejected—with huge consequences for Gingrich, Romney, and even Santorum.

An hour or so after the Republican debate in Jacksonville on January 26, Romney’s chief strategist, Stuart Stevens, was in the spin room employing his iPad as a weapon. Stevens asked if I knew how many times Gingrich was mentioned in Reagan’s memoir. Calling up the text onscreen and searching the document, he revealed the answer: zero. Stevens then asked the same about a different memoir—Jack Abramoff’s. Here the number of mentions was larger: thirteen. Stevens asked, “What does that tell you?” I ventured, “That Newt is full of shit?” Stevens: “You said it, buddy.”

Stevens’s parlor trick was a minor, albeit delightful, element of the two-front assault waged by Team Romney on Gingrich in Florida: strafing him from the air with negative ads and badgering him on the ground, which involved not only working the press but sending operatives to Gingrich’s every event to offer instant rebuttals. One objective here was to refute Gingrich’s claims to being at once instrumental to the Reagan Revolution and a Washington outsider; another was to rattle him, to piss him off, to get inside his head.

Together with two stellar debate showings by Romney, the anti-Newt incursion accomplished all that and more, driving Gingrich to fits of defensive distraction, undisguised irritation, and an in toto effort in Florida that was every bit as feeble as his South Carolina bid had been robust. And in its indiscipline, lassitude, and wackiness—how many news cycles did he squander on that freaking lunar colony?—it made manifest why he was never a plausible Republican nominee. But while Gingrich today seems an afterthought, his role in shaping the contours of the contest cannot be overstated.

“Of all the candidates, he has had the biggest impact,” says Steve Schmidt, McCain’s 2008 chief strategist. “By making the case he made against Romney, Gingrich did a significant amount of damage to him, both in the primary and in the general, if Romney does become the nominee.”

The damage Schmidt is talking about in the latter case revolves around independent voters. By pressing Romney on Bain and his tax returns, Gingrich helped create the context for his rival’s errors. “The toughest thing in a campaign is when there’s synergy between your opponents’ attacks on the left and right,” Schmidt explains. “The same criticisms of Romney being made by Democrats are being echoed by his Republican challengers. And when criticism becomes ecumenical, that really impacts independent voters.”

And how. An NBC News–Wall Street Journal poll in late January found Romney’s unfavorability rating among independents had risen twenty points, from 22 to 42 percent, over the previous two months. “It’s not as though they have said Bain has disqualified him or that he can’t be trusted because of his taxes, but this has created a gulf between him and the average voter,” one of the pollsters behind the survey, Peter Hart, told the Washington Post. “Bain and the taxes just reinforce the sense that this person is in a different world.”

Every presidential candidate faces a trade-off between maintaining his viability with independents and catering to his party’s base. The difficulty for Romney is that, even as his appeal to the middle has sharply waned, the lack of enthusiasm for him on the right has remained acute. Even in Florida, where Romney’s fourteen-point victory was broad and sweeping, he was beaten soundly by Gingrich among very conservative voters and strong tea-party adherents.

To a large extent, Romney’s concurrent problems with conservatives and independents are of his own making. His campaign’s incineration of Gingrich in Florida, though perhaps necessary and certainly skillful, also contributed mightily to alienating the center while doing nothing to remedy his main malady in the eyes of conservatives: the absence of a positive message that resonates with them, coupled with a tic-like tendency to commit unforced errors that exacerbate their doubts that he is one of their own. Crystallizing this phenomenon was an episode that took place the morning after Florida, when, on CNN, Romney disgorged another gem: “I’m in this race because I care about Americans. I’m not concerned about the very poor. We have a safety net there. If it needs repair, I’ll fix it.”

With these few short sentences in what should have been a moment of triumph for him, Romney managed to send the wrong message to an array of factions. To independent voters, “I’m not concerned about the very poor” sounds callous. To conservative intellectuals and activists, talk about fixing the safety net—as opposed to pursuing policies that enable the poor to free themselves from government dependency—is rank apostasy. And to congressional Republicans, the comment reflected a glaring lack of familiarity with the party’s anti-poverty positions. “Electeds were flabbergasted,” says a veteran K Street player. “Even moderate Republican members, if they’ve been here for more than four months, get dipped in the empowerment agenda.”

A week later, Romney attempted to repair part of the damage with his speech at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference—and promptly put his foot in it again. In an address in which he employed the word conservative or some variation of it 24 times, as if trying to prove he is a member of the tribe through sheer incantation, his use of the adverb severely to express the depth of his conviction raised eyebrows inside and outside the hall. “The most retarded thing I have ever heard a Republican candidate say” was the verdict of one strategist with ample experience in GOP presidential campaigns.

At CPAC in 2008, Romney had used the convocation to announce he was dropping out of the race, as the party was rallying around McCain despite long-held suspicions of him among movement conservatives. Four years later, the rightward drift of the GOP and its shirts-skins fractiousness meant that Romney was still struggling to close the deal. His problems doing so were more, well, severe than his vocabulary—for by then Santorum had achieved liftoff and was streaking across the Republican sky.

The launching pad for Santorum was the trio of states that held contests on February 7: Colorado, Minnesota, and Missouri. His sweep of all three was unexpected to everyone but him—Santorum is a confident man—and reflected a grievous miscalculation on the part of Team Romney, which only barely played in Colorado and ignored the other two. “The idiocy to do that with all of the resources they have; there’s no limit to their money,” Rollins says. “It’s that kind of arrogance: ‘We won Florida; it’s over.’ That was four years ago. That’s not this time. This time it’s trench warfare all the way, and somebody’s gonna keep rising up, and it’s now Santorum.”

For many Democrats, the idea of Santorum elevating beyond the level of a punch line is all but inconceivable. The extremeness of the former Pennsylvania senator’s views on social issues—from the out-front homophobia that led him to compare gay sex to “man-on-child, man-on-dog, or whatever the case may be,” to his adamant opposition to contraception and abortion even in cases of rape or incest—have long made him the subject of scorn and ridicule on the left, in the center, and on the Internet. (Even with his newfound fame, the first result of a Google search for his name is spreading santorum.com, a site dealing with “frothy” matters too coarse to discuss in a family magazine, and also in this one.)

But in a Republican-nomination contest, these views are not necessarily liabilities, and are even assets in some quarters—which doesn’t mean Santorum is without vulnerabilities in the context of his party. On spending, earmarks, and labor relations, he is by no means pure in conservative terms. He has been embroiled in ethics issues and is a bone-deep creature of the Beltway. Then there is his personality: “In the Senate as well as his home state, Santorum often struck people as arrogant and headstrong, preachy and judgmental,” writes Byron York in the Washington Examiner. Or, as a Republican lobbyist puts it to me, “When he was in the Senate, he was probably the most friendless guy there.”

That the Romney campaign will hit Santorum hard on virtually all this (and more) is a given; indeed, it already is, holding regular conference calls with surrogates to attack him, outspending him by three to one on TV ads in Michigan (if the super-pacs on each side are included in the totals). “The Romney campaign has realized there’s nothing it can do to communicate Romney’s record in a way that moves the needle, so their focus is on disqualifying Santorum as a plausible nominee and authentic conservative,” says a top GOP operative. “Can Santorum survive the onslaught? Gingrich certainly couldn’t.”

Santorum may be a different story, however—less erratic, less prone to light himself on fire, less saddled with XXXL baggage. “Santorum is a much more sympathetic character than Gingrich,” says the Evangelical leader Richard Land. “If a guy has 57 percent negatives, you can carpet-bomb him with impunity. But if Romney comes out swinging for Santorum, people are going to get angry. It’s a lot harder to demonize him than Gingrich.”

If Santorum can weather the welter of attacks, his combination of governing and ideological bona fides might make him Romney’s bête noire. “The one thing Romney had to avoid that’s a mortal threat to him was an ideological contest with someone who has the credentials to be commander-in-chief,” says Schmidt. “And Santorum, as a three-term member of Congress and two-term senator, clears that hurdle, especially running against a one-term governor. That’s why the race is more wide open now than at any other point before—because Romney is dealing for the first time with a plausible nominee in the eyes of Republican voters, where it’s absolutely impossible to get around his right flank.”

Nowhere is this more true than on social issues, naturally. Whatever risks it might pose in the general election, the controversy over contraceptives, the Catholic Church, and the Obama administration has been an unalloyed blessing for Santorum in the Republican-nomination fight. Popping up unexpectedly, it has shifted what the political sharpies call the “issue matrix” in an awkward direction for Romney and a comfortable one for Santorum, and is likely to help the latter further solidify his already firm hold over a voting bloc with which his rival is notably weak.

Evangelicals and other devout voters are, to be sure, Santorum’s most ardent supporters within the grassroots coalition. He has also demonstrated considerable traction with tea-party supporters, carrying the largest proportion of them in Iowa (29 percent) against four far-right foes. But equally crucial is the non-college-educated, blue-collar vote, which accounts for more than half the electorate in Michigan, as well as Super Tuesday states such as Ohio, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. So far in 2012, Santorum has not done consistently well with this cohort. But between his policy focus on reviving American manufacturing, a biography that includes growing up in Western Pennsylvania steel country and a coal-miner grandfather, and a Joe Six-Pack–meets–Mister Rogers demeanor, he seems well positioned to make inroads here.

If Santorum can consolidate the support of these groups as Gingrich did momentarily in South Carolina, the battle between him and his amalgam of red-hots and Romney and his army of regulars will be pitched—and, depending on what happens on Tuesday in Michigan, maybe bloody and protracted.

The day before Santorum’s speech in Macomb County, Romney delivers a talk of his own right next door in Oakland County, at the Greater Farmington–Livonia Chamber of Commerce Lunch. Oakland couldn’t be more different from Macomb: affluent, professional, well educated, and reasonably diverse. The Romney crowd reflects the divergence, decked out in suits and ties where Santorum’s crowd was all sweatshirts and baggy jeans. The event begins with Michigan governor Rick Snyder bestowing his endorsement on Romney. Beaming and amped up, Romney begins with a paean that reads like a parody—and instantly goes viral:

“I was born and raised here. I love this state. It seems right here. Trees are the right height. I like seeing the lakes. I love the lakes. There’s something very special here. The Great Lakes, but also all the little inland lakes that dot the parts of Michigan. I love cars. I grew up totally in love with cars. It used to be, in the fifties and sixties, if you showed me one square foot of almost any part of a car, I could tell you what brand it was, the model, and so forth. Now, with all the Japanese cars, I’m not quite so good at it. But I still know the American cars pretty well and drive a Mustang. I love cars. I love American cars. And long may they rule the world, let me tell ya.”

In his TV ads as well as on the stump, Romney has been slapping the favorite-son card on the table like a drunk at a game of strip poker, and is leaning hard on the state GOP Establishment to help him win the hand. “Regardless of the polls that show Santorum with a lead, it’s still Romney’s to lose,” says consultant and former state-party executive director Greg McNeilly. “He has massive organizational strength Santorum can’t match.” Bill Ballenger, editor of Inside Michigan Politics newsletter, agrees: “Romney has a list of endorsements as long as both your arms. He’s raised far more money here than any other candidate, including Barack Obama. Santorum is a total cipher. He’s an unknown. And he has not done anything here.”

But the savviest political players in the state also allow that, as McNeilly puts it, “the race is in flux in a way that defies conventional wisdom,” that anti-Establishment sentiments are running high in the state, and therefore Santorum might just pull off an upset. And while Eric Ferhnstrom, Romney’s spokesman, insists the primary is not a must-win for his boss, others close to the candidate admit that losing, in the words of one of them, would be “absolutely, completely fucking horrible.”

The reality is that even winning Michigan (and Arizona the same day) may not be enough to rescue Romney from the rough. “Every money guy I know thinks Romney can’t win a general election,” says a respected Washington player and presidential-campaign veteran. “Our guys on Capitol Hill are moving into survival-of-the-fittest, only-worrying-about-themselves mode. They think the damage to Romney may be done and may be irreversible—and now he might not even be the nominee. So Romney not only has to win Michigan and Arizona, but he has to have a resounding knockout on Super Tuesday or he’s gonna be in real, real trouble.”

Yet the likelihood of Romney delivering a KO, or even a TKO, on Super Tuesday is slight. According to University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato, at least five of the ten states with contests on March 6—Georgia, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia—have electorates in which more than 40 percent of voters are Evangelical. That presents a significant hurdle to Romney and advantage to Santorum, provided he emerges from Michigan with either a win or a narrow enough loss that his momentum isn’t utterly halted. True, Santorum isn’t on the ballot in Virginia. But also true is that Alaska, Idaho, and North Dakota, for which there is no data available on the size of the born-again contingent, are all caucus states in which religious conservatives (and tea-partyers) are thick on the ground.

None of which suggests that Santorum, even if he wins in Michigan, is much better positioned to deal a death blow to Romney on Super Tuesday. “I still am a believer that you’ve gotta have some kind of an organization, some kind of resources, beyond living off a super-pac, to go all the way,” says Rollins. “I can’t imagine Santorum just all of a sudden putting it together and racing to the finish line. So my sense is Super Tuesday may be a day that gets split up. And, I mean, Romney’s not gonna quit. He’s spent six years of his life running for this thing, and he will have delegates. And it’s not like if he drops out all the Establishment are gonna jump on Santorum. They’re all gonna basically say Santorum can’t win.”

This kind of thinking is increasingly widespread among Republicans. And it is giving rise to ever-louder (though still private) calls for a Romney-Santorum alternative to enter the race after Super Tuesday. Last week, Politico reported that Indiana governor Mitch Daniels and New Jersey governor Chris Christie have been subject to mounting entreaties by GOP leaders to dive in. And so, I am reliably told, have Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan and Jeb Bush.

Logistically speaking, the white-knight scenario is a stretch, but nothing like as fantastical as it sounds. After Super Tuesday, there are still seven states—five voting on June 5, including winner-take-all monsters California and New Jersey—where it is possible to get on the ballot. And if a stud Republican were to put himself forward, as a “tippy-top Republican” told Politico’s Mike Allen, “he would suck all the oxygen out of the race. People wouldn’t even give a shit who won on these other dates in March that are after Super Tuesday. I mean, seriously, who would care? It would all be about a new savior.”

Even if such a savior won all five states, he would be far away from the 1,145 delegates necessary to secure the nomination. But given the proportional nature of many of the contests in March, April, and May, there’s a decent chance no one else would obtain that number, either. Meaning Republicans would be staring down the barrel of a brokered or contested convention in Tampa this summer.

Could it happen? Yes, it could, especially if, not to beat a dead equine, Romney loses Michigan on Tuesday. But will it happen? Don’t hold your breath, particularly since none of the putative white knights evince the slightest interest in putting themselves in the near-suicidal position of having to assemble and fund a general-election campaign on the fly with only 67 days left between the convention and November 6. And while a contested convention—at which the existing candidates all arrive in Tampa shy of 1,145 and the nomination is settled through backroom dealing—is more conceivable, the likeliest outcome of that would be the eventual coronation of Romney or Santorum. (Sigh.)

The question is, what will happen then—not just to them but to their party?

For Democrats, the answer is easy, reflexive, and comforting: Barack Obama wins. And at this moment, they have reasons to think so—starting with the historical precedents suggesting that the Romney-Santorum death match and the intraparty tensions it represents will undermine the eventual nominee. “Goldwater hurt Nixon in 1960, Rockefeller hurt Goldwater in 1964, and Reagan hurt Ford in 1976,” says historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. “When splits become open in the party, it’s never a good thing.”

Then there is the current polling. The RealClearPolitics average of public surveys pitting the president head-to-head against Romney gives Obama a 4.8 percent lead, and 6.1 percent against Santorum. (Against Gingrich, the gap widens to 13.7 percent.)

Not one of the president’s presiding reelection gurus—David Axelrod, David Plouffe, Jim Messina—believes that, come November, their margin of victory will be as big as even the smallest of those numbers. All along, they have been operating from the assumption that the Republican base will be riled up and ready to turn out in droves on Election Day. That Richard Land is right when he asserts that, for all the lack of enthusiasm for the extant crop of candidates, no one should ever “underestimate the ability of President Obama to rally conservatives to vote against him.” That, given the still fragile state of the nation’s recovery, the high percentage of voters who continue to regard the country as on the wrong track, and the possibility that Iran or Europe might throw the world a nasty curveball in the months ahead, 2012 will be a closer-run election than 2008. That, in other words, it’s still perfectly conceivable that Obama might lose this thing.

If that happens, the implications for the Republican Party will be straightforward: It will be reshaped in the image of whichever of the candidates becomes president-elect. A Romney victory would signal the resurgence of the regulars, while one by Santorum would usher in an era of red-hot regnancy.

But if Obama prevails, precisely the opposite dynamic is likely to kick in: a period of bitter recriminations followed by a reformation (or counterreformation) of the GOP. This, please recall, was what many Republicans were counting on to happen in the wake of their party’s loss of the White House and seats in the House and Senate in 2008. Instead, Republicans seized on a strategy of relentless opposition to Obama, which proved politically effective in 2010 but left the party as bereft of new ideas, a constructive agenda, or a coherent governing philosophy as before. With Obama having looked beatable months ago, a botched bid to oust him—especially if coupled with a failure to take over the Senate—would usher in a full-blown Republican conflagration, followed by an effort to rise from the ashes by doing the opposite of what caused the meltdown of 2012.

What that would mean for the GOP would differ wildly depending on which of the two current front-runners, along with the coalition that elevated him to the nomination, is blamed for the debacle. “If Romney is the nominee and he loses in November, I think we’ll see a resurgence of the charismatic populist right,” says Robert Alan Goldberg, a history professor at the University of Utah and author of a biography of Barry Goldwater. “Not only will [the grassroots wing] say that Romney led Republicans down the road to defeat, but that the whole type of conservatism he represents is doomed.”

Goldberg points out that this is what happened in 1976, when the party stuck with Ford over Reagan, was beaten by Carter, and went on to embrace the Gipper’s brand of movement conservatism four years later. So who does Goldberg think might be ascendant in the aftermath of a Romney licking? “Sarah Palin,” he replies. “She’s an outsider, she has no Washington or Wall Street baggage, she’s electric—and she’s waiting, because if Romney doesn’t win, she will be welcomed in.”

But if it’s Santorum who is the standard-bearer and then he suffers an epic loss, a different analogy will be apt: Goldwater in 1964. (And, given the degree of the challenges Santorum would face in attracting female voters, epic it might well be.) As Kearns Goodwin points out, the rejection of the Arizona senator’s ideology and policies led the GOP to turn back in 1968 to Nixon, “a much more moderate figure, despite the incredible corruption of his time in office.” For Republicans after 2012, a similar repudiation of the populist, culture-warrior coalition that is fueling Santorum’s surge would open the door to the many talented party leaders—Daniels, Christie, Bush, Ryan, Bobby Jindal—waiting in the wings for 2016, each offering the possibility of refashioning the GOP into a serious and forward-thinking enterprise.

Only the most mindless of ideologues reject the truism that America would be best served by the presence of two credible governing parties instead of the situation that currently obtains. A Santorum nomination would be seen by many liberals as a scary and retrograde proposition. And no doubt it would make for a wild ride, with enough talk of Satan, abortifacients, and sweater vests to drive any sane man bonkers. But in the long run, it might do a world of good, compelling Republicans to return to their senses—and forge ahead into the 21st century. Which is why all people of common sense and goodwill might consider, in the days ahead, adopting a slogan that may strike them as odd, perverse, or even demented: Go, Rick, go.

Original Article

Source: nymag

Author: John Heilemann

All of which is to say that when Santorum takes the podium to address a Michigan Faith & Freedom Coalition rally in Shelby Charter Township, the 1,500 souls he sees before him are his kind of people—and soon enough he is speaking their language. To explain how America has always differed from other nations, Santorum invokes the Almighty: “We believe … we are children of a loving God.” To elucidate the evils of Obamacare, Dodd-Frank, and cap-and-trade, he inveighs against liberal elites: “They want to control you, because like the kings of old, they believe they know better than you.” To highlight what’s at stake in 2012, he unfurls a grand (and entirely farkakte) historical flourish: “This decision will be starker than at any time since the election of 1860”—you know, the one featuring Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas on the eve of the Civil War.

But before the nation faces that decision, Michigan has its own to make: between him and Mitt Romney in the Republican primary that takes place on February 28. “Do you want somebody who can go up against Barack Obama, take him on on the big issues … or do you want someone who can just manage Washington a little bit better?” Santorum asks, as the audience rises cheering to its feet. “That’s your choice. What does Michigan have to say?”

What Michiganders are telling pollsters is that their affections are split evenly between the two men, despite Romney’s status as the scion of one of the Wolverine State’s great political families. In Ohio, arguably the most important of ten states with primaries or caucuses on Super Tuesday, March 6, two recent surveys found Santorum holding a wide lead there, and the Gallup national tracking poll put him ahead of Romney by eight points as of February 24. Taken together, all this more than makes clear that Santorum has emerged as the dominant conservative alternative to Romney. It illustrates a shift in momentum so pronounced that, unless Romney takes Michigan and fares strongly on Super Tuesday, his ascension to his party’s nomination will be in serious jeopardy, as the calls for a late-entering white-knight candidate escalate—and odds of an up-for-grabs Republican convention rise. “Right now, I’d say they’re one in five,” says one of the GOP’s grandest grandees. “If Romney doesn’t put this thing away by Super Tuesday, I’d say they’re closer to 50-50.”

That Mitt Romney finds himself so imperiled by Rick Santorum—Rick Santorum!—is just the latest in a series of jaw-dropping developments in what has been the most volatile, unpredictable, and just plain wackadoodle Republican-nomination contest ever. Part of the explanation lies in Romney’s lameness as a candidate, in Santorum’s strength, and in the sudden efflorescence of social issues in what was supposed to be an all-economy-all-the-time affair. But even more important have been the seismic changes within the Republican Party. “Compared to 2008, all the candidates are way to the right of John McCain,” says longtime conservative activist Jeff Bell. “The fact that Romney is running with basically the same views as then but is seen as too moderate tells you that the base has moved rightward and doesn’t simply want a conservative candidate—it wants a very conservative one.”

The transfiguration of the GOP isn’t only about ideology, however. It is also about demography and temperament, as the party has grown whiter, less well schooled, more blue-collar, and more hair-curlingly populist. The result has been a party divided along the lines of culture and class: Establishment versus grassroots, secular versus religious, upscale versus downscale, highfalutin versus hoi polloi. And with those divisions have arisen the competing electoral coalitions—shirts versus skins, regulars versus red-hots—represented by Romney and Santorum, which are now increasingly likely to duke it out all spring.

Few Republicans greet that prospect sanguinely, though some argue that it will do little to hamper the party’s capacity to defeat Obama in the fall. “It’s reminiscent of the contest between Obama and Clinton,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell recently opined. “[That] didn’t seem to have done [Democrats] any harm in the general election, and I don’t think this contest is going to do us any harm, either.”

Yet the Democratic tussle in 2008, which featured two undisputed heavyweights with few ideological discrepancies between them, may be an exception that proves the rule. Certainly Republican history suggests as much: Think of 1964 and the scrap between the forces aligned with Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller, or 1976, between backers of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan. On both occasions, the result was identical: a party disunited, a nominee debilitated, a general election down the crapper.

With such precedents in mind, many Republicans are already looking past 2012. If either Romney or Santorum gains the nomination and then falls before Obama, flubbing an election that just months ago seemed eminently winnable, it will unleash a GOP apocalypse on November 7—followed by an epic struggle between the regulars and red-hots to refashion the party. And make no mistake: A loss is what the GOP’s political class now expects. “Six months before this thing got going, every Republican I know was saying, ‘We’re gonna win, we’re gonna beat Obama,’ ” says former Reagan strategist Ed Rollins. “Now even those who’ve endorsed Romney say, ‘My God, what a fucking mess.’ ”

Should Romney ultimately fail to become the Republican standard-bearer, history will record with precision the day the wheels came off the wagon—January 19. Until that morning, his march to the nomination was proceeding even more smoothly than he and his advisers had hoped. The apparent eight-vote win in Iowa. The landslide in New Hampshire. And then the double-digit leads in South Carolina polling, positioning him to pull off a historic early-state trifecta. But in the space of a few hours, Romney was serially (and surreally) battered by unwelcome events: three tracking polls putting him behind Gingrich for the first time in 2012; word from Iowa that his victory there was being snatched away and handed to Santorum; Rick Perry’s exit from the race and endorsement of Gingrich; and Newt’s masterly mau-mauing of CNN’s John King at a debate in Charleston over a (foolish, inartful, walking-blithely-into-a-buzzsaw) question about accusations by Gingrich’s second wife that he’d sought an “open marriage.”

By the next morning, it was evident that Romney was on his way to defeat in South Carolina, though few would have forecast the scale of the drubbing to come. In truth, any expectations Romney would win there were always overblown. His long-standing weakness with Evangelical voters was always likely to make him a hard sell to an electorate in which nearly two thirds self-identify as born-again. And that, in turn, led Team Romney to devote few resources to the state. “They had no real structure in South Carolina—none, nada,” says Jon Huntsman’s former chief strategist, John Weaver. “They ended up with a few figurehead endorsements and some late hires, but they had nothing on the ground.”

But South Carolina also laid bare weaknesses in Romney’s candidacy, some already well known, others brand spanking new—and devastating to the core rationale behind his campaign. All through 2011, Romney had focused laserlike on the economy, arguing that his private-sector background made him best suited to tackle Obama on the election’s central issue. Sure, Romney inspired little passion in the Republican base; but his rivals were clueless, cartoonish, or crackers, and with the GOP intent above all on ousting the incumbent, the presumption was that Romney’s combination of experience and presidential bearing would conquer all. “The Romney folks faced a fork in the road between the electable route and the ideological route,” says the manager of a previous Republican presidential campaign. “And they decided to go all-in on electability.”

Romney and his people never expected, however, to be confronted in the Republican phase of the race with a raft of challenges related to the legitimacy of his wealth. But first on his record at Bain Capital and then on his tax returns, that is what occurred. With Gingrich and Perry sounding more like commenters on Daily Kos than Republicans, Romney coughed up a remarkable collection of gaffes: from his fear of pink slips to his enjoyment of firing people to his “not very much” in speaker’s fees (when they totaled $374,327 last year).

For many Republicans, Romney’s maladroitness in addressing the issues at hand was worrisome, to put it mildly. Here he was handing Obama’s people a blooper reel that would let them paint him as a hybrid of Gordon Gekko and Thurston Howell III. “Republicans were saying, ‘This is the guy who’s gonna be carrying the ball for our side, defending the private sector?’ ” Rollins says incredulously. “Warren Buffett would kick his ass in a debate, let alone Obama.”

Nor were Romney’s rehearsed turns on the hustings appreciably better. From Iowa through New Hampshire, his campaign events had been progressively pared back and whittled down. By the time he reached South Carolina, they had achieved a certain purity—the purity of the null set. The climactic moment in them came when Romney would recite (and offer attendant textual analysis that would make Stanley Fish beat his head against a wall) the lyrics of “America the Beautiful.” Even staunch Romney allies were abashed by this sadly persistent, and persistently sad, rhetorical trope. “I have never seen anything more ridiculous or belittling,” a prominent Romney fund-raiser says.

Gingrich, by contrast, was on fire in South Carolina, and not just at the debates. His final event on the night before the primary, a rally aboard the USS Yorktown aircraft carrier in Charleston Harbor, included an encounter with a heckler who shouted out, “When will you release your ethics report?”—from a congressional investigation of Gingrich in the nineties.

Gingrich replied with a spontaneity and forcefulness as foreign to Romney as Urdu. “Actually, if you’d do a little research instead of shouting mindlessly, you’d discover the entire thing is available online in the Thomas system”—the online congressional database Gingrich brought into existence as Speaker of the House in 1995—“and you can print it out,” he fired back. “I think it is 900 pages. When you get done reading it, let me know if there are any questions.” The crowd cheered loudly and then Gingrich delivered the coup de grâce: “I assume you’re for the candidate who’s afraid to release his income taxes.”

But Gingrich wasn’t merely a superior performer to Romney on the stump. With his hot-eyed imprecations against Obama, his race-freighted mugging of Fox News’s Juan Williams at the debate in Myrtle Beach, his unbridled (if theatrical and hypocritical) enmity toward the media and East Coast elites more broadly, and his relentless ideological attacks on his rival as a timid “Massachusetts moderate,” he was far more deeply in sync with the raging id of the party’s ascendant populist wing.

The coalescence of the various elements of that wing around Gingrich accounted for the 40 to 28 percent pistol-whipping he administered to Romney on Primary Day—and marked the sharpening of the shirts-skins schism that would play out from then on. According to the exit polls, Gingrich captured 45 percent (to Romney’s 21) of Evangelical voters, 48 percent (to 21) of strong tea-party supporters, and 47 percent (to 22) of non–college graduates. Romney, meanwhile, held his own with the groups making up what the journalist Ron Brownstein has dubbed the GOP’s “managerial wing”—richer, better-educated, less godly, more pragmatic voters. One trouble for Romney was that this assemblage constitutes less than half his party now. But even more disconcerting was that he lost badly to Gingrich among South Carolinians who said that the most crucial candidate quality was the ability to beat Obama—which suggested not simply that ideology trumped electability but that for many Republicans, hard-core conservative ideology was tantamount to electability.

Thus did Romney find himself facing his first existential peril. The influential conservative blogger Erik Erickson, on the grounds that South Carolina represented less an embrace of Gingrich than a grassroots rejection of the front-runner, his themeless pudding of a campaign, and the Establishment support of it, encouraged Romney to “refine his message, not sharpen his knives” as the race moved to Florida. But that suggestion would be rejected—with huge consequences for Gingrich, Romney, and even Santorum.

An hour or so after the Republican debate in Jacksonville on January 26, Romney’s chief strategist, Stuart Stevens, was in the spin room employing his iPad as a weapon. Stevens asked if I knew how many times Gingrich was mentioned in Reagan’s memoir. Calling up the text onscreen and searching the document, he revealed the answer: zero. Stevens then asked the same about a different memoir—Jack Abramoff’s. Here the number of mentions was larger: thirteen. Stevens asked, “What does that tell you?” I ventured, “That Newt is full of shit?” Stevens: “You said it, buddy.”

Stevens’s parlor trick was a minor, albeit delightful, element of the two-front assault waged by Team Romney on Gingrich in Florida: strafing him from the air with negative ads and badgering him on the ground, which involved not only working the press but sending operatives to Gingrich’s every event to offer instant rebuttals. One objective here was to refute Gingrich’s claims to being at once instrumental to the Reagan Revolution and a Washington outsider; another was to rattle him, to piss him off, to get inside his head.

Together with two stellar debate showings by Romney, the anti-Newt incursion accomplished all that and more, driving Gingrich to fits of defensive distraction, undisguised irritation, and an in toto effort in Florida that was every bit as feeble as his South Carolina bid had been robust. And in its indiscipline, lassitude, and wackiness—how many news cycles did he squander on that freaking lunar colony?—it made manifest why he was never a plausible Republican nominee. But while Gingrich today seems an afterthought, his role in shaping the contours of the contest cannot be overstated.

“Of all the candidates, he has had the biggest impact,” says Steve Schmidt, McCain’s 2008 chief strategist. “By making the case he made against Romney, Gingrich did a significant amount of damage to him, both in the primary and in the general, if Romney does become the nominee.”

The damage Schmidt is talking about in the latter case revolves around independent voters. By pressing Romney on Bain and his tax returns, Gingrich helped create the context for his rival’s errors. “The toughest thing in a campaign is when there’s synergy between your opponents’ attacks on the left and right,” Schmidt explains. “The same criticisms of Romney being made by Democrats are being echoed by his Republican challengers. And when criticism becomes ecumenical, that really impacts independent voters.”

And how. An NBC News–Wall Street Journal poll in late January found Romney’s unfavorability rating among independents had risen twenty points, from 22 to 42 percent, over the previous two months. “It’s not as though they have said Bain has disqualified him or that he can’t be trusted because of his taxes, but this has created a gulf between him and the average voter,” one of the pollsters behind the survey, Peter Hart, told the Washington Post. “Bain and the taxes just reinforce the sense that this person is in a different world.”

Every presidential candidate faces a trade-off between maintaining his viability with independents and catering to his party’s base. The difficulty for Romney is that, even as his appeal to the middle has sharply waned, the lack of enthusiasm for him on the right has remained acute. Even in Florida, where Romney’s fourteen-point victory was broad and sweeping, he was beaten soundly by Gingrich among very conservative voters and strong tea-party adherents.

To a large extent, Romney’s concurrent problems with conservatives and independents are of his own making. His campaign’s incineration of Gingrich in Florida, though perhaps necessary and certainly skillful, also contributed mightily to alienating the center while doing nothing to remedy his main malady in the eyes of conservatives: the absence of a positive message that resonates with them, coupled with a tic-like tendency to commit unforced errors that exacerbate their doubts that he is one of their own. Crystallizing this phenomenon was an episode that took place the morning after Florida, when, on CNN, Romney disgorged another gem: “I’m in this race because I care about Americans. I’m not concerned about the very poor. We have a safety net there. If it needs repair, I’ll fix it.”

With these few short sentences in what should have been a moment of triumph for him, Romney managed to send the wrong message to an array of factions. To independent voters, “I’m not concerned about the very poor” sounds callous. To conservative intellectuals and activists, talk about fixing the safety net—as opposed to pursuing policies that enable the poor to free themselves from government dependency—is rank apostasy. And to congressional Republicans, the comment reflected a glaring lack of familiarity with the party’s anti-poverty positions. “Electeds were flabbergasted,” says a veteran K Street player. “Even moderate Republican members, if they’ve been here for more than four months, get dipped in the empowerment agenda.”

A week later, Romney attempted to repair part of the damage with his speech at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference—and promptly put his foot in it again. In an address in which he employed the word conservative or some variation of it 24 times, as if trying to prove he is a member of the tribe through sheer incantation, his use of the adverb severely to express the depth of his conviction raised eyebrows inside and outside the hall. “The most retarded thing I have ever heard a Republican candidate say” was the verdict of one strategist with ample experience in GOP presidential campaigns.

At CPAC in 2008, Romney had used the convocation to announce he was dropping out of the race, as the party was rallying around McCain despite long-held suspicions of him among movement conservatives. Four years later, the rightward drift of the GOP and its shirts-skins fractiousness meant that Romney was still struggling to close the deal. His problems doing so were more, well, severe than his vocabulary—for by then Santorum had achieved liftoff and was streaking across the Republican sky.

The launching pad for Santorum was the trio of states that held contests on February 7: Colorado, Minnesota, and Missouri. His sweep of all three was unexpected to everyone but him—Santorum is a confident man—and reflected a grievous miscalculation on the part of Team Romney, which only barely played in Colorado and ignored the other two. “The idiocy to do that with all of the resources they have; there’s no limit to their money,” Rollins says. “It’s that kind of arrogance: ‘We won Florida; it’s over.’ That was four years ago. That’s not this time. This time it’s trench warfare all the way, and somebody’s gonna keep rising up, and it’s now Santorum.”

For many Democrats, the idea of Santorum elevating beyond the level of a punch line is all but inconceivable. The extremeness of the former Pennsylvania senator’s views on social issues—from the out-front homophobia that led him to compare gay sex to “man-on-child, man-on-dog, or whatever the case may be,” to his adamant opposition to contraception and abortion even in cases of rape or incest—have long made him the subject of scorn and ridicule on the left, in the center, and on the Internet. (Even with his newfound fame, the first result of a Google search for his name is spreading santorum.com, a site dealing with “frothy” matters too coarse to discuss in a family magazine, and also in this one.)

But in a Republican-nomination contest, these views are not necessarily liabilities, and are even assets in some quarters—which doesn’t mean Santorum is without vulnerabilities in the context of his party. On spending, earmarks, and labor relations, he is by no means pure in conservative terms. He has been embroiled in ethics issues and is a bone-deep creature of the Beltway. Then there is his personality: “In the Senate as well as his home state, Santorum often struck people as arrogant and headstrong, preachy and judgmental,” writes Byron York in the Washington Examiner. Or, as a Republican lobbyist puts it to me, “When he was in the Senate, he was probably the most friendless guy there.”

That the Romney campaign will hit Santorum hard on virtually all this (and more) is a given; indeed, it already is, holding regular conference calls with surrogates to attack him, outspending him by three to one on TV ads in Michigan (if the super-pacs on each side are included in the totals). “The Romney campaign has realized there’s nothing it can do to communicate Romney’s record in a way that moves the needle, so their focus is on disqualifying Santorum as a plausible nominee and authentic conservative,” says a top GOP operative. “Can Santorum survive the onslaught? Gingrich certainly couldn’t.”

Santorum may be a different story, however—less erratic, less prone to light himself on fire, less saddled with XXXL baggage. “Santorum is a much more sympathetic character than Gingrich,” says the Evangelical leader Richard Land. “If a guy has 57 percent negatives, you can carpet-bomb him with impunity. But if Romney comes out swinging for Santorum, people are going to get angry. It’s a lot harder to demonize him than Gingrich.”

If Santorum can weather the welter of attacks, his combination of governing and ideological bona fides might make him Romney’s bête noire. “The one thing Romney had to avoid that’s a mortal threat to him was an ideological contest with someone who has the credentials to be commander-in-chief,” says Schmidt. “And Santorum, as a three-term member of Congress and two-term senator, clears that hurdle, especially running against a one-term governor. That’s why the race is more wide open now than at any other point before—because Romney is dealing for the first time with a plausible nominee in the eyes of Republican voters, where it’s absolutely impossible to get around his right flank.”

Nowhere is this more true than on social issues, naturally. Whatever risks it might pose in the general election, the controversy over contraceptives, the Catholic Church, and the Obama administration has been an unalloyed blessing for Santorum in the Republican-nomination fight. Popping up unexpectedly, it has shifted what the political sharpies call the “issue matrix” in an awkward direction for Romney and a comfortable one for Santorum, and is likely to help the latter further solidify his already firm hold over a voting bloc with which his rival is notably weak.

Evangelicals and other devout voters are, to be sure, Santorum’s most ardent supporters within the grassroots coalition. He has also demonstrated considerable traction with tea-party supporters, carrying the largest proportion of them in Iowa (29 percent) against four far-right foes. But equally crucial is the non-college-educated, blue-collar vote, which accounts for more than half the electorate in Michigan, as well as Super Tuesday states such as Ohio, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. So far in 2012, Santorum has not done consistently well with this cohort. But between his policy focus on reviving American manufacturing, a biography that includes growing up in Western Pennsylvania steel country and a coal-miner grandfather, and a Joe Six-Pack–meets–Mister Rogers demeanor, he seems well positioned to make inroads here.

If Santorum can consolidate the support of these groups as Gingrich did momentarily in South Carolina, the battle between him and his amalgam of red-hots and Romney and his army of regulars will be pitched—and, depending on what happens on Tuesday in Michigan, maybe bloody and protracted.

The day before Santorum’s speech in Macomb County, Romney delivers a talk of his own right next door in Oakland County, at the Greater Farmington–Livonia Chamber of Commerce Lunch. Oakland couldn’t be more different from Macomb: affluent, professional, well educated, and reasonably diverse. The Romney crowd reflects the divergence, decked out in suits and ties where Santorum’s crowd was all sweatshirts and baggy jeans. The event begins with Michigan governor Rick Snyder bestowing his endorsement on Romney. Beaming and amped up, Romney begins with a paean that reads like a parody—and instantly goes viral:

“I was born and raised here. I love this state. It seems right here. Trees are the right height. I like seeing the lakes. I love the lakes. There’s something very special here. The Great Lakes, but also all the little inland lakes that dot the parts of Michigan. I love cars. I grew up totally in love with cars. It used to be, in the fifties and sixties, if you showed me one square foot of almost any part of a car, I could tell you what brand it was, the model, and so forth. Now, with all the Japanese cars, I’m not quite so good at it. But I still know the American cars pretty well and drive a Mustang. I love cars. I love American cars. And long may they rule the world, let me tell ya.”

In his TV ads as well as on the stump, Romney has been slapping the favorite-son card on the table like a drunk at a game of strip poker, and is leaning hard on the state GOP Establishment to help him win the hand. “Regardless of the polls that show Santorum with a lead, it’s still Romney’s to lose,” says consultant and former state-party executive director Greg McNeilly. “He has massive organizational strength Santorum can’t match.” Bill Ballenger, editor of Inside Michigan Politics newsletter, agrees: “Romney has a list of endorsements as long as both your arms. He’s raised far more money here than any other candidate, including Barack Obama. Santorum is a total cipher. He’s an unknown. And he has not done anything here.”

But the savviest political players in the state also allow that, as McNeilly puts it, “the race is in flux in a way that defies conventional wisdom,” that anti-Establishment sentiments are running high in the state, and therefore Santorum might just pull off an upset. And while Eric Ferhnstrom, Romney’s spokesman, insists the primary is not a must-win for his boss, others close to the candidate admit that losing, in the words of one of them, would be “absolutely, completely fucking horrible.”

The reality is that even winning Michigan (and Arizona the same day) may not be enough to rescue Romney from the rough. “Every money guy I know thinks Romney can’t win a general election,” says a respected Washington player and presidential-campaign veteran. “Our guys on Capitol Hill are moving into survival-of-the-fittest, only-worrying-about-themselves mode. They think the damage to Romney may be done and may be irreversible—and now he might not even be the nominee. So Romney not only has to win Michigan and Arizona, but he has to have a resounding knockout on Super Tuesday or he’s gonna be in real, real trouble.”

Yet the likelihood of Romney delivering a KO, or even a TKO, on Super Tuesday is slight. According to University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato, at least five of the ten states with contests on March 6—Georgia, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia—have electorates in which more than 40 percent of voters are Evangelical. That presents a significant hurdle to Romney and advantage to Santorum, provided he emerges from Michigan with either a win or a narrow enough loss that his momentum isn’t utterly halted. True, Santorum isn’t on the ballot in Virginia. But also true is that Alaska, Idaho, and North Dakota, for which there is no data available on the size of the born-again contingent, are all caucus states in which religious conservatives (and tea-partyers) are thick on the ground.

None of which suggests that Santorum, even if he wins in Michigan, is much better positioned to deal a death blow to Romney on Super Tuesday. “I still am a believer that you’ve gotta have some kind of an organization, some kind of resources, beyond living off a super-pac, to go all the way,” says Rollins. “I can’t imagine Santorum just all of a sudden putting it together and racing to the finish line. So my sense is Super Tuesday may be a day that gets split up. And, I mean, Romney’s not gonna quit. He’s spent six years of his life running for this thing, and he will have delegates. And it’s not like if he drops out all the Establishment are gonna jump on Santorum. They’re all gonna basically say Santorum can’t win.”

This kind of thinking is increasingly widespread among Republicans. And it is giving rise to ever-louder (though still private) calls for a Romney-Santorum alternative to enter the race after Super Tuesday. Last week, Politico reported that Indiana governor Mitch Daniels and New Jersey governor Chris Christie have been subject to mounting entreaties by GOP leaders to dive in. And so, I am reliably told, have Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan and Jeb Bush.

Logistically speaking, the white-knight scenario is a stretch, but nothing like as fantastical as it sounds. After Super Tuesday, there are still seven states—five voting on June 5, including winner-take-all monsters California and New Jersey—where it is possible to get on the ballot. And if a stud Republican were to put himself forward, as a “tippy-top Republican” told Politico’s Mike Allen, “he would suck all the oxygen out of the race. People wouldn’t even give a shit who won on these other dates in March that are after Super Tuesday. I mean, seriously, who would care? It would all be about a new savior.”

Even if such a savior won all five states, he would be far away from the 1,145 delegates necessary to secure the nomination. But given the proportional nature of many of the contests in March, April, and May, there’s a decent chance no one else would obtain that number, either. Meaning Republicans would be staring down the barrel of a brokered or contested convention in Tampa this summer.

Could it happen? Yes, it could, especially if, not to beat a dead equine, Romney loses Michigan on Tuesday. But will it happen? Don’t hold your breath, particularly since none of the putative white knights evince the slightest interest in putting themselves in the near-suicidal position of having to assemble and fund a general-election campaign on the fly with only 67 days left between the convention and November 6. And while a contested convention—at which the existing candidates all arrive in Tampa shy of 1,145 and the nomination is settled through backroom dealing—is more conceivable, the likeliest outcome of that would be the eventual coronation of Romney or Santorum. (Sigh.)

The question is, what will happen then—not just to them but to their party?

For Democrats, the answer is easy, reflexive, and comforting: Barack Obama wins. And at this moment, they have reasons to think so—starting with the historical precedents suggesting that the Romney-Santorum death match and the intraparty tensions it represents will undermine the eventual nominee. “Goldwater hurt Nixon in 1960, Rockefeller hurt Goldwater in 1964, and Reagan hurt Ford in 1976,” says historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. “When splits become open in the party, it’s never a good thing.”

Then there is the current polling. The RealClearPolitics average of public surveys pitting the president head-to-head against Romney gives Obama a 4.8 percent lead, and 6.1 percent against Santorum. (Against Gingrich, the gap widens to 13.7 percent.)

Not one of the president’s presiding reelection gurus—David Axelrod, David Plouffe, Jim Messina—believes that, come November, their margin of victory will be as big as even the smallest of those numbers. All along, they have been operating from the assumption that the Republican base will be riled up and ready to turn out in droves on Election Day. That Richard Land is right when he asserts that, for all the lack of enthusiasm for the extant crop of candidates, no one should ever “underestimate the ability of President Obama to rally conservatives to vote against him.” That, given the still fragile state of the nation’s recovery, the high percentage of voters who continue to regard the country as on the wrong track, and the possibility that Iran or Europe might throw the world a nasty curveball in the months ahead, 2012 will be a closer-run election than 2008. That, in other words, it’s still perfectly conceivable that Obama might lose this thing.

If that happens, the implications for the Republican Party will be straightforward: It will be reshaped in the image of whichever of the candidates becomes president-elect. A Romney victory would signal the resurgence of the regulars, while one by Santorum would usher in an era of red-hot regnancy.

But if Obama prevails, precisely the opposite dynamic is likely to kick in: a period of bitter recriminations followed by a reformation (or counterreformation) of the GOP. This, please recall, was what many Republicans were counting on to happen in the wake of their party’s loss of the White House and seats in the House and Senate in 2008. Instead, Republicans seized on a strategy of relentless opposition to Obama, which proved politically effective in 2010 but left the party as bereft of new ideas, a constructive agenda, or a coherent governing philosophy as before. With Obama having looked beatable months ago, a botched bid to oust him—especially if coupled with a failure to take over the Senate—would usher in a full-blown Republican conflagration, followed by an effort to rise from the ashes by doing the opposite of what caused the meltdown of 2012.

What that would mean for the GOP would differ wildly depending on which of the two current front-runners, along with the coalition that elevated him to the nomination, is blamed for the debacle. “If Romney is the nominee and he loses in November, I think we’ll see a resurgence of the charismatic populist right,” says Robert Alan Goldberg, a history professor at the University of Utah and author of a biography of Barry Goldwater. “Not only will [the grassroots wing] say that Romney led Republicans down the road to defeat, but that the whole type of conservatism he represents is doomed.”

Goldberg points out that this is what happened in 1976, when the party stuck with Ford over Reagan, was beaten by Carter, and went on to embrace the Gipper’s brand of movement conservatism four years later. So who does Goldberg think might be ascendant in the aftermath of a Romney licking? “Sarah Palin,” he replies. “She’s an outsider, she has no Washington or Wall Street baggage, she’s electric—and she’s waiting, because if Romney doesn’t win, she will be welcomed in.”

But if it’s Santorum who is the standard-bearer and then he suffers an epic loss, a different analogy will be apt: Goldwater in 1964. (And, given the degree of the challenges Santorum would face in attracting female voters, epic it might well be.) As Kearns Goodwin points out, the rejection of the Arizona senator’s ideology and policies led the GOP to turn back in 1968 to Nixon, “a much more moderate figure, despite the incredible corruption of his time in office.” For Republicans after 2012, a similar repudiation of the populist, culture-warrior coalition that is fueling Santorum’s surge would open the door to the many talented party leaders—Daniels, Christie, Bush, Ryan, Bobby Jindal—waiting in the wings for 2016, each offering the possibility of refashioning the GOP into a serious and forward-thinking enterprise.

Only the most mindless of ideologues reject the truism that America would be best served by the presence of two credible governing parties instead of the situation that currently obtains. A Santorum nomination would be seen by many liberals as a scary and retrograde proposition. And no doubt it would make for a wild ride, with enough talk of Satan, abortifacients, and sweater vests to drive any sane man bonkers. But in the long run, it might do a world of good, compelling Republicans to return to their senses—and forge ahead into the 21st century. Which is why all people of common sense and goodwill might consider, in the days ahead, adopting a slogan that may strike them as odd, perverse, or even demented: Go, Rick, go.

Original Article

Source: nymag

Author: John Heilemann

No comments:

Post a Comment