Like many residents of the San Juan Islands, Johannes Krieger's livelihood is inextricably tied to the sea. He runs kayak and whale-watching tours here in the northwest corner of Washington State.

"Any oil spill would be pretty devastating. An Exxon Valdez type of spill would blanket the entire San Juan Island area," says Krieger of Friday Harbor. "Even a 160-foot luxury yacht striking a rock can make for a pretty big spill."

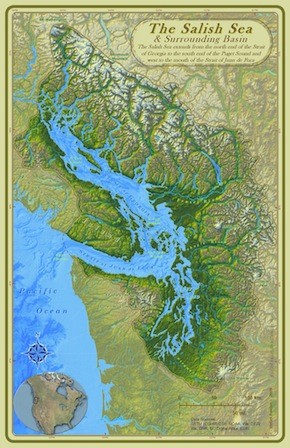

Krieger, 38, is a lifelong resident of this archipelago, which consistently ranks among the world's top tourist destinations. He is well acquainted with the substantial number of ships that already weave between the islands' 300-plus miles of shoreline, alongside resident orca whales, sea birds, salmon and a sensitive herring population that is critical to the survival of many critters. And he is becoming more aware of proposals to expand U.S. and Canadian oil and coal exports to Asia, which would significantly increase the traffic through these narrow, often rough channels.

The prospect concerns him. "This is a relatively small area that's got lots and lots of rocky islands and reefs. Most of the area is not super deep," Krieger adds. "I understand that industry at this time of our civilization still needs to be out there to some degree, but it needs to be done safely."

Earlier this month, Texas-based energy company Kinder Morgan announced plans to expand its Trans Mountain pipeline running between the Alberta oil sands and a port in Vancouver, B.C. The move would roughly triple the number of deployed tankers operating in the area, each carrying about four times as much crude oil as the Exxon Valdez. SSA Marine, a division of the world's largest cargo terminal operator Carrix, also filed an application this month to build North America's largest coal export terminal just south of the Canadian border -- within sight of the San Juan Islands.

Protesters continue to battle the projects from both sides of the U.S.-Canada border.

Between these two projects alone, approximately 1,700 more large vessel trips would be made in and out of the Pacific Northwest waters that contain the San Juan Islands, known as the Salish Sea, each year. According to the projects' proponents, the region would see a large influx of desperately needed jobs, too. Also on the books are plans for at least five more coal ports in Washington and Oregon, as well as another oil sands pipeline: Enbridge's controversial Northern Gateway, which would terminate a little further north on the B.C. coast. (The Canadian government is making clear that it's not an either-or situation with regards to these westward pipes and the proposed Keystone XL pipeline between Alberta and refineries on the Gulf Coast of Texas.)

It's simple math, according to Lovel Pratt, a San Juan County Council representative: "The more traffic you have, the higher the likelihood of an incident."

One engine failure, bad storm or imperfect maneuver between the reefs, rocks and other ships could mean devastation to the people and marine life that rely on the special ecosystems along these coasts, experts warn. Pratt worries that the challenges and potential consequences could be even greater than with the BP Gulf oil spill, which after two years is still impacting countless lives.

"When the Gulf spill happened, we had days before any of the oil came to any shore. Here, we would have hours. And we're dealing with the unique challenges of our ecology and geography that includes so much coastline and sensitive ecosystems," says Pratt, who has become vocal on the issue since taking office in 2008.

But not everyone thinks that the extra traffic would add up to an increased risk of a spill -- at least not when tighter regulations are put into place.

"SSA Marine has already agreed to create a vessel traffic safety plan that would specify the routes, spacing between ships and docking considerations, so that all of those details would be worked out before the project begins operation," SSA Marine spokesman Gary Smith tells The Huffington Post.

Andrew Galarnyk, a spokesman for Kinder Morgan Canada, notes that tankers have been "safely calling in local waters for more than 60 years without incident."

"While we believe effective spill response capabilities are in place," Galarnyk said in an email Wednesday, "we will continue to support efforts to ensure that appropriate resources are in place for the safe conduct of tankers through local waters."

Capt. Frantz Coe, president of the Puget Sound Pilots, a team of marine pilots that help guide large vessels safely through area waters, says that an increase in risky situations doesn't have to translate into a decrease in safety.

"The expansions will have a big impact. It will create more opportunities for an accident," says Coe, but he added, "Whatever risk they bring, we find a way to mitigate it -- maybe we have two pilots, tug escorts, tell them to run slower, or travel through different meeting points." He notes that he has not been involved in single oil spill to date: "Knock on wood."

In addition to prevention measures, Pratt, the San Juan County Council representative, wants the region to build up its capacity to respond to a spill. The types of petroleum products that might spew into the Salish Sea from these carriers, she notes, may behave quite differently than, say, Gulf of Mexico crude oil or other substances with which we're more familiar.

The bulk coal carriers run on a waste product of fuel oil processing called bunker fuel. "Bunker fuel is one of the most toxic fuels, tar sands oil is worse," says Matt Krogh of the nonprofit RE Sources for Sustainable Communities in Bellingham, Wash.

Unlike conventional crude, the stuff sent west from Canadian oil sands is a mixture of unrefined tar and a cocktail of potentially toxic solvents that allows the thick material to be pumped through a pipeline. The resulting substance may be more difficult to clean up, as responders to the million-plus gallons of spilled tar sands chemicals in Michigan's Kalamazoo River recently learned. Much of this so-called diluted bitumen can sink quickly, raising doubts about the future adequacy of using standard skimmers, floating oil booms and other tools there were enlisted in the BP and Exxon Valdez clean-up efforts.

The exact makeup of the material piped by Kinder Morgan in its Trans Mountain pipeline, how it would behave in large bodies of saltwater and the potential health risks for local residents and clean-up workers remain open questions.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that the Salish Sea straddles the U.S.-Canada border. If the ships are coming out of Canada and don't stop in a U.S. port, explains Linda Pilkey-Jarvis, an oil spill expert with the Washington State Department of Ecology, then Washington State has no jurisdiction. "We bear the risks but have to rely on the Canadian government to set comparable standards and focus on prevention," Pilkey-Jarvis says.

The Canadian government recently shut down a regional oil spill response center.

Of course, the concerns of environmental and public health advocates opposed to the expansion of coal and oil exports go well beyond open-water spills, or even another Kalamazoo River-like pipeline incident. As HuffPost described in November, people argue that SSA Marine's proposed Cherry Point coal port would expose residents to dangerous coal dust and diesel fumes from both the ships and the trains that would carry the coal in from the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming. Then there's the coal-fired power plant pollution that could come back to haunt the western U.S. via winds from Asia.

Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber (D) is now calling for an extensive federal government review of exporting coal to Asia through Northwest ports. As The Oregonian reported on Wednesday, the six potential coal export projects in Oregon and Washington could ship more than 150 million tons of coal each year, more than double current U.S. exports.

"When you look at this from a global level, there is this huge sucking sound of the world economy desperate for carbon-based fuels. They're trying to suck it out of the U.S.," RE Sources' Krogh says. "Trying to keep it in the ground wherever it is and trying to remove the market pressure to export is gonna be the key."

As Krogh also acknowledges, even the best the preventative measures and response capacity may not be enough to avoid a catastrophic oil spill.

Krieger, the business owner from the San Juan Islands, recalls a disconcerting incident during one of his kayak lessons. A tug boat was towing two barges when one got disconnected. "That distracted me quite a bit," he says. "Here, I saw this barge starting to float back with the current and then coming closer and closer to shore. Ultimately, the tug miraculously came around and lassoed it back into place."

"This shows you that accidents do happen," Krieger says. "That's the bottom line. No matter how much precaution you take, or how experienced you are, stuff is going to happen."

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Lynne Peeples

"Any oil spill would be pretty devastating. An Exxon Valdez type of spill would blanket the entire San Juan Island area," says Krieger of Friday Harbor. "Even a 160-foot luxury yacht striking a rock can make for a pretty big spill."

Krieger, 38, is a lifelong resident of this archipelago, which consistently ranks among the world's top tourist destinations. He is well acquainted with the substantial number of ships that already weave between the islands' 300-plus miles of shoreline, alongside resident orca whales, sea birds, salmon and a sensitive herring population that is critical to the survival of many critters. And he is becoming more aware of proposals to expand U.S. and Canadian oil and coal exports to Asia, which would significantly increase the traffic through these narrow, often rough channels.

The prospect concerns him. "This is a relatively small area that's got lots and lots of rocky islands and reefs. Most of the area is not super deep," Krieger adds. "I understand that industry at this time of our civilization still needs to be out there to some degree, but it needs to be done safely."

Earlier this month, Texas-based energy company Kinder Morgan announced plans to expand its Trans Mountain pipeline running between the Alberta oil sands and a port in Vancouver, B.C. The move would roughly triple the number of deployed tankers operating in the area, each carrying about four times as much crude oil as the Exxon Valdez. SSA Marine, a division of the world's largest cargo terminal operator Carrix, also filed an application this month to build North America's largest coal export terminal just south of the Canadian border -- within sight of the San Juan Islands.

Protesters continue to battle the projects from both sides of the U.S.-Canada border.

Between these two projects alone, approximately 1,700 more large vessel trips would be made in and out of the Pacific Northwest waters that contain the San Juan Islands, known as the Salish Sea, each year. According to the projects' proponents, the region would see a large influx of desperately needed jobs, too. Also on the books are plans for at least five more coal ports in Washington and Oregon, as well as another oil sands pipeline: Enbridge's controversial Northern Gateway, which would terminate a little further north on the B.C. coast. (The Canadian government is making clear that it's not an either-or situation with regards to these westward pipes and the proposed Keystone XL pipeline between Alberta and refineries on the Gulf Coast of Texas.)

It's simple math, according to Lovel Pratt, a San Juan County Council representative: "The more traffic you have, the higher the likelihood of an incident."

One engine failure, bad storm or imperfect maneuver between the reefs, rocks and other ships could mean devastation to the people and marine life that rely on the special ecosystems along these coasts, experts warn. Pratt worries that the challenges and potential consequences could be even greater than with the BP Gulf oil spill, which after two years is still impacting countless lives.

"When the Gulf spill happened, we had days before any of the oil came to any shore. Here, we would have hours. And we're dealing with the unique challenges of our ecology and geography that includes so much coastline and sensitive ecosystems," says Pratt, who has become vocal on the issue since taking office in 2008.

But not everyone thinks that the extra traffic would add up to an increased risk of a spill -- at least not when tighter regulations are put into place.

"SSA Marine has already agreed to create a vessel traffic safety plan that would specify the routes, spacing between ships and docking considerations, so that all of those details would be worked out before the project begins operation," SSA Marine spokesman Gary Smith tells The Huffington Post.

Andrew Galarnyk, a spokesman for Kinder Morgan Canada, notes that tankers have been "safely calling in local waters for more than 60 years without incident."

"While we believe effective spill response capabilities are in place," Galarnyk said in an email Wednesday, "we will continue to support efforts to ensure that appropriate resources are in place for the safe conduct of tankers through local waters."

Capt. Frantz Coe, president of the Puget Sound Pilots, a team of marine pilots that help guide large vessels safely through area waters, says that an increase in risky situations doesn't have to translate into a decrease in safety.

"The expansions will have a big impact. It will create more opportunities for an accident," says Coe, but he added, "Whatever risk they bring, we find a way to mitigate it -- maybe we have two pilots, tug escorts, tell them to run slower, or travel through different meeting points." He notes that he has not been involved in single oil spill to date: "Knock on wood."

In addition to prevention measures, Pratt, the San Juan County Council representative, wants the region to build up its capacity to respond to a spill. The types of petroleum products that might spew into the Salish Sea from these carriers, she notes, may behave quite differently than, say, Gulf of Mexico crude oil or other substances with which we're more familiar.

The bulk coal carriers run on a waste product of fuel oil processing called bunker fuel. "Bunker fuel is one of the most toxic fuels, tar sands oil is worse," says Matt Krogh of the nonprofit RE Sources for Sustainable Communities in Bellingham, Wash.

Unlike conventional crude, the stuff sent west from Canadian oil sands is a mixture of unrefined tar and a cocktail of potentially toxic solvents that allows the thick material to be pumped through a pipeline. The resulting substance may be more difficult to clean up, as responders to the million-plus gallons of spilled tar sands chemicals in Michigan's Kalamazoo River recently learned. Much of this so-called diluted bitumen can sink quickly, raising doubts about the future adequacy of using standard skimmers, floating oil booms and other tools there were enlisted in the BP and Exxon Valdez clean-up efforts.

The exact makeup of the material piped by Kinder Morgan in its Trans Mountain pipeline, how it would behave in large bodies of saltwater and the potential health risks for local residents and clean-up workers remain open questions.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that the Salish Sea straddles the U.S.-Canada border. If the ships are coming out of Canada and don't stop in a U.S. port, explains Linda Pilkey-Jarvis, an oil spill expert with the Washington State Department of Ecology, then Washington State has no jurisdiction. "We bear the risks but have to rely on the Canadian government to set comparable standards and focus on prevention," Pilkey-Jarvis says.

The Canadian government recently shut down a regional oil spill response center.

Of course, the concerns of environmental and public health advocates opposed to the expansion of coal and oil exports go well beyond open-water spills, or even another Kalamazoo River-like pipeline incident. As HuffPost described in November, people argue that SSA Marine's proposed Cherry Point coal port would expose residents to dangerous coal dust and diesel fumes from both the ships and the trains that would carry the coal in from the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming. Then there's the coal-fired power plant pollution that could come back to haunt the western U.S. via winds from Asia.

Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber (D) is now calling for an extensive federal government review of exporting coal to Asia through Northwest ports. As The Oregonian reported on Wednesday, the six potential coal export projects in Oregon and Washington could ship more than 150 million tons of coal each year, more than double current U.S. exports.

"When you look at this from a global level, there is this huge sucking sound of the world economy desperate for carbon-based fuels. They're trying to suck it out of the U.S.," RE Sources' Krogh says. "Trying to keep it in the ground wherever it is and trying to remove the market pressure to export is gonna be the key."

As Krogh also acknowledges, even the best the preventative measures and response capacity may not be enough to avoid a catastrophic oil spill.

Krieger, the business owner from the San Juan Islands, recalls a disconcerting incident during one of his kayak lessons. A tug boat was towing two barges when one got disconnected. "That distracted me quite a bit," he says. "Here, I saw this barge starting to float back with the current and then coming closer and closer to shore. Ultimately, the tug miraculously came around and lassoed it back into place."

"This shows you that accidents do happen," Krieger says. "That's the bottom line. No matter how much precaution you take, or how experienced you are, stuff is going to happen."

Original Article

Source: Huff

Author: Lynne Peeples

No comments:

Post a Comment