It was, after all, only four short years ago. And it didn’t go so well. The Bush economy is one of the worst on record. Median wages dropped. Poverty worsened. Inequality increased. Surpluses turned into deficits. Monthly job growth was weaker than it had been in any expansion since 1954. Economic growth was sluggish. And that’s before you count the financial crisis that unfurled on his watch. Add the collapse to the equation, and Bush’s record goes from “not so good” to “I can’t bear to look.”

Was all that his fault? Of course not. No economy is entirely under the president’s control. He didn’t create the tech bubble or 9/11. His responsibility for the financial crisis is, at best, partial. But Bush’s economic policies -- including massive, deficit-financed tax cuts, and his reappointing of Alan Greenspan to lead the Federal Reserve -- mattered. And, rightly or wrongly, the American people blame him for the aftermath. He left office one of the most unpopular presidents in U.S. history. And the anger has stuck: A recent YouGov poll found that 56 percent blame Bush “a great deal” or “a lot” for economic problems. Only 41 percent said the same about President Obama.

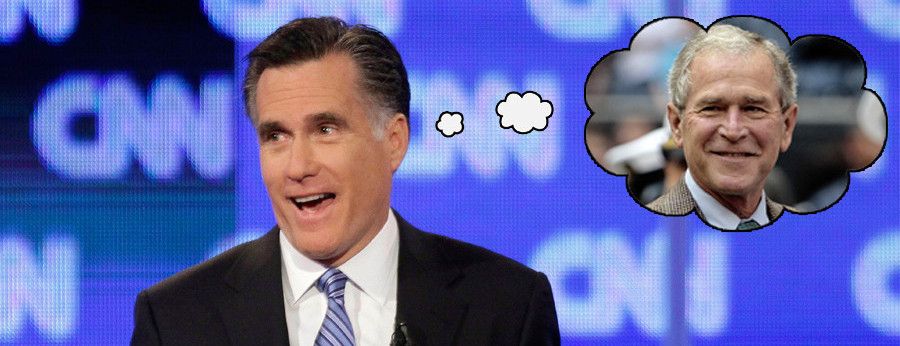

Given all that, you’d think Republicans would be running from anything or anyone who even vaguely reminded Americans of our 43rd president. In fact, the GOP seems eager to get the old gang back together.

Last week, when CNN asked House Speaker John Boehner whom Mitt Romney, the likely GOP presidential nominee, should choose as his vice presidential running mate, he named Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, Ohio Sen. Rob Portman and Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. Daniels and Portman served as budget directors in the Bush White House. Perhaps more surprising, a variety of big-name Republicans have openly yearned for Jeb Bush to get the nod — and before that, to run for the nomination itself.

Meanwhile, Romney’s campaign staff is thick with Bush administration veterans. Two of his economic advisers — N. Greg Mankiw and Glenn Hubbard — served as chief economists for Bush. His policy director, Lanhee Chen, worked on health policy in the Bush White House.

Some of this is unavoidable: Presidential administrations tend to suck up a political party’s best talent. The Obama White House, for instance, is full of Clinton veterans. But in the Obama White House, the Clinton veterans haven’t really acted like Clinton veterans.

Where, in the 1990s, they were known for cutting the deficit and loosening regulations on the financial sector, they now applied themselves to crafting a deficit-financed stimulus package and re-regulating the financial sector. They arguably didn’t go far enough on either count. But they went further, certainly, than Congress expected to go. This was, they contended, a different time, and it required different policies — even though the Clinton record was broadly considered a success.

The Romney campaign’s rethink has been shallower. The candidate’s platform calls for extending all the Bush tax cuts and then adding more. It calls for repealing many of the new financial regulations but says nothing about what it would put in their place. The difference is that Romney talks much more about deficit reduction than Bush did and spends much less time emphasizing policies to reform the education system or expand health-care options for seniors. Where Bush sold himself as a “compassionate conservative,” Romney has sold himself as “severely conservative.”

Still, there’s little that couldn’t have been there in 2000, or 1996, or 1988. Reading Romney’s policies, you would never know that the nation is still facing high unemployment rates or that it just came through the worst financial crisis in a generation. You certainly wouldn’t think we’d just emerged from a decade in which large tax cuts and financial deregulation led to major economic distress.

This is not necessarily the fault of Romney’s advisers, who have rethought elements of the Republican Party platform and have taken risks. Mankiw, for instance, has eloquently argued for a tax on carbon emissions and for a looser monetary policy. Hubbard has pushed efforts to encourage mass refinancing. Vin Weber, another Romney adviser, was an advocate of the Bowles-Simpson deficit-reduction plan. But Romney hasn’t gone for any of these policies. There’s nothing in his campaign platform that couldn’t have been in Bush’s platform. In fact, most of it was.

The irony of this is that, of late, the Obama camp is reverting to more traditionally Clintonian policies. Now that the worst of the crisis is over, the president’s advisers are pushing harder for a deficit-reduction package. Now that they’re facing a Republican Congress that doesn’t want to give an inch, they’re pushing more small, high-polling policy ideas — the very “politics of school uniforms” for which they once derided Clinton’s campaign. Now that the Bush tax cuts are set to expire, they’re arguing for letting the rates on the rich revert to Clinton-era levels. They’re even sending Clinton out to campaign for Obama. The election might end up being Bush vs. Clinton, even as it most likely will be between Obama and Romney.

That could be a problem for the Romney campaign. Because just as most voters remember the Bush years, they remember the Clinton years, too. And they liked them a lot more.

Original Article

Source: washington post

Author: Ezra Klein

Was all that his fault? Of course not. No economy is entirely under the president’s control. He didn’t create the tech bubble or 9/11. His responsibility for the financial crisis is, at best, partial. But Bush’s economic policies -- including massive, deficit-financed tax cuts, and his reappointing of Alan Greenspan to lead the Federal Reserve -- mattered. And, rightly or wrongly, the American people blame him for the aftermath. He left office one of the most unpopular presidents in U.S. history. And the anger has stuck: A recent YouGov poll found that 56 percent blame Bush “a great deal” or “a lot” for economic problems. Only 41 percent said the same about President Obama.

Given all that, you’d think Republicans would be running from anything or anyone who even vaguely reminded Americans of our 43rd president. In fact, the GOP seems eager to get the old gang back together.

Last week, when CNN asked House Speaker John Boehner whom Mitt Romney, the likely GOP presidential nominee, should choose as his vice presidential running mate, he named Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, Ohio Sen. Rob Portman and Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. Daniels and Portman served as budget directors in the Bush White House. Perhaps more surprising, a variety of big-name Republicans have openly yearned for Jeb Bush to get the nod — and before that, to run for the nomination itself.

Meanwhile, Romney’s campaign staff is thick with Bush administration veterans. Two of his economic advisers — N. Greg Mankiw and Glenn Hubbard — served as chief economists for Bush. His policy director, Lanhee Chen, worked on health policy in the Bush White House.

Some of this is unavoidable: Presidential administrations tend to suck up a political party’s best talent. The Obama White House, for instance, is full of Clinton veterans. But in the Obama White House, the Clinton veterans haven’t really acted like Clinton veterans.

Where, in the 1990s, they were known for cutting the deficit and loosening regulations on the financial sector, they now applied themselves to crafting a deficit-financed stimulus package and re-regulating the financial sector. They arguably didn’t go far enough on either count. But they went further, certainly, than Congress expected to go. This was, they contended, a different time, and it required different policies — even though the Clinton record was broadly considered a success.

The Romney campaign’s rethink has been shallower. The candidate’s platform calls for extending all the Bush tax cuts and then adding more. It calls for repealing many of the new financial regulations but says nothing about what it would put in their place. The difference is that Romney talks much more about deficit reduction than Bush did and spends much less time emphasizing policies to reform the education system or expand health-care options for seniors. Where Bush sold himself as a “compassionate conservative,” Romney has sold himself as “severely conservative.”

Still, there’s little that couldn’t have been there in 2000, or 1996, or 1988. Reading Romney’s policies, you would never know that the nation is still facing high unemployment rates or that it just came through the worst financial crisis in a generation. You certainly wouldn’t think we’d just emerged from a decade in which large tax cuts and financial deregulation led to major economic distress.

This is not necessarily the fault of Romney’s advisers, who have rethought elements of the Republican Party platform and have taken risks. Mankiw, for instance, has eloquently argued for a tax on carbon emissions and for a looser monetary policy. Hubbard has pushed efforts to encourage mass refinancing. Vin Weber, another Romney adviser, was an advocate of the Bowles-Simpson deficit-reduction plan. But Romney hasn’t gone for any of these policies. There’s nothing in his campaign platform that couldn’t have been in Bush’s platform. In fact, most of it was.

The irony of this is that, of late, the Obama camp is reverting to more traditionally Clintonian policies. Now that the worst of the crisis is over, the president’s advisers are pushing harder for a deficit-reduction package. Now that they’re facing a Republican Congress that doesn’t want to give an inch, they’re pushing more small, high-polling policy ideas — the very “politics of school uniforms” for which they once derided Clinton’s campaign. Now that the Bush tax cuts are set to expire, they’re arguing for letting the rates on the rich revert to Clinton-era levels. They’re even sending Clinton out to campaign for Obama. The election might end up being Bush vs. Clinton, even as it most likely will be between Obama and Romney.

That could be a problem for the Romney campaign. Because just as most voters remember the Bush years, they remember the Clinton years, too. And they liked them a lot more.

Original Article

Source: washington post

Author: Ezra Klein

No comments:

Post a Comment