Today, the Senate Judiciary Committee heard several hours of testimony on gun violence, from luminaries up and down the spectrum of opinion on reducing gun violence. Today's hearings precede the larger debate to come on what action, if any, Congress will take in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. Measures that are said to be "on the table" include some heavy lifts -- a proposed assault weapons ban, limiting the availability of high-capacity magazines -- and some things that could get passed with relative ease, such as strengthening the current background check regime.

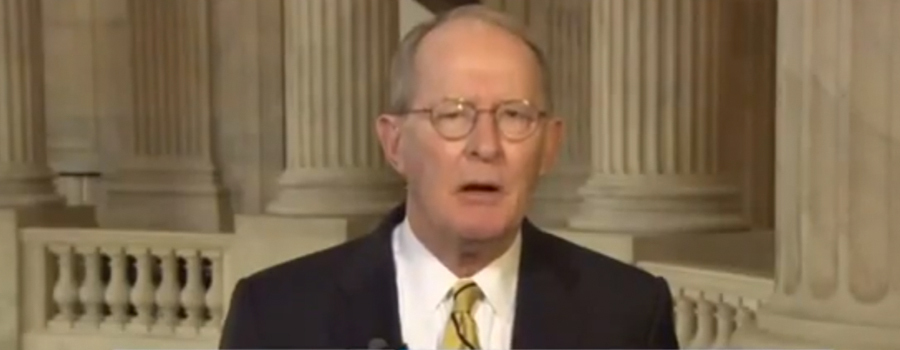

Or maybe it could get passed with relative ease, anyway? I have some doubts now that Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), who's generally thought to be in the Senate's "reasonable caucus," was asked a direct question about the matter, and he opted to change the subject to ...video games? Yes, video games, for some reason.

CHUCK TODD (MSNBC): Can you envision a way of supporting the universal background checks bill?

LAMAR ALEXANDER: Chuck, I'm going to wait and see on all of these bills. I think video games is [sic] a bigger problem than guns, because video games affect people. But the First Amendment limits what we can do about video games, and the Second Amendment to the Constitution limits what we can do about guns.

Concerns about video game violence have been twinned to concerns about gun violence from as far back as the Columbine shooting, when pundits fussed and fretted over how Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold enjoyed yesteryear's most popular first-person shooter, "Doom." (Also, they were vaguely "goth," according to observers, which for a time made life hard for Bauhaus fans who just wanted to be alone and sad and misunderstood.) I was never too convinced by the argument: Video games, unlike the act of shooting up an entire school of children, were and remain popular, with hundreds of thousands millions of people partaking in the escape. That some mass-murderers occasionally participated in that culture seems to be incidental at best -- a tiny bit of statistical effluvia that should be written off as insignificant at the outset.

"Video games affect people," of course, is not actually an argument. Monet paintings affect people. Long waits at the DMV affect people. If there's anything that diminishes my worry about whether or not Alexander will seriously consider the prospect of beefing up background checks, it would be the way that this thought sort of floated out of him like flatulence, unattached to anything serious. If I could assure Alexander of anything, however, I would point out that we have spared no expense in trying to ascertain the ways in which video games affect people, up to and including whether they can be connected to violent tendencies in real life.

Historically, it's been a hard case to make. I can point you immediately to this article from the Washington Post's Max Fischer, in which he runs down the statistics on the 10 largest global markets for video games and finds "no evident, statistical correlation between video game consumption and gun-related killings."

It's true that Americans spend billions of dollars on video games every year and that the United States has the highest firearm murder rate in the developed world. But other countries where video games are popular have much lower firearm-related murder rates. In fact, countries where video game consumption is highest tend to be some of the safest countries in the world, likely a product of the fact that developed or rich countries, where consumers can afford expensive games, have on average much less violent crime.

But there's no reason to stop there. Over at Kotaku, Jason Schreier has a lengthy piece about the past quarter century of research into video games and their connection to violence or, as it's more popularly termed, "aggression." Schreier gives the matter a thorough going-over, presenting the case for concern alongside the case against. It's absolutely fair to say that some studies have ended with the conclusion that a correlation between violence and video games exists. But it's also fair to say that many have not. Nevertheless Schreier gives serious, scholarly consideration to the matter, and so I'd urge people to go read the whole thing.

For the time being, however, here's the key data point: "The first major violent video game study took place in 1984." Yes, that's right, we are approaching the 30th anniversary of considering the impact of a globally popular entertainment medium on mass shootings in the U.S. And as Schreier points out, a sizable infrastructure has grown to support this never-ending research.

One factor worth considering: who funds all of these studies?

"Some scholars have taken research funding from advocacy groups, which is just as bad as taking research funding from the video game industry, as far as I'm concerned," said Ferguson, pointing to groups like the now-defunct National Institute on Media and the Family and the Center For Successful Parenting, a family-values group that sets out to find the negative effects in violent media.

"It's something we need to stop on both sides."

...

And what of the video game industry? I reached out to Dan Hewitt, a representative for the Entertainment Software Association (the group that helps regulate and represent gaming companies), to ask.

"ESA hasn't funded any research in any way," Hewitt told me in an e-mail. "Everything that's out there and that we talk about is completely free from any ESA influence or financing."

Ultimately, I reach a different conclusion than Scheier: I find this all to be a bit boondoggle-y, while he contends that "it's hard to argue with Obama's assertion that we need more research into the effects of violent video games."

Oh, that's right. We're going to spend another bag of ducats re-studying this anyway. So in the end, Alexander is getting his wish.

Speaking for myself, I believe that law-abiding citizens are law-abiding citizens, and I'm unaccustomed to demonizing them. Moreover, I think we're not as far ahead on solving this problem as we could be, because the well has long been poisoned by people who have demonized gun owners who have done nothing wrong. I'm very amenable to the argument that we should not pick on the lowest common denominator in this debate, and I hope that my antipathy to high-capacity magazines and my worry about military-style arms being in public circulation can stand alongside these sentiments. I think that the fact that 75 percent of NRA members agree that strengthening the background check system is a worthwhile policy to pursue goes a long way to proving that it doesn't go after the lowest common denominator, and I certainly think that it doesn't.

But let's not trade the pointless demonization of law-abiding gun owners for the pointless demonization of law-abiding video game enthusiasts. Gamers are not saints, and there are certainly aspects to gamer culture that disturb me. (Just ask Anita Sarkeesian.) But the simple fact of the matter is that nobody becomes more materially dangerous to society by dint of owning a Playstation. And I'd rather face down someone armed with a copy of "Call Of Duty" than someone armed with a Sig Sauer any day of the week.

Original Article

Source: huffington post

Author: Jason Linkins

Or maybe it could get passed with relative ease, anyway? I have some doubts now that Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), who's generally thought to be in the Senate's "reasonable caucus," was asked a direct question about the matter, and he opted to change the subject to ...video games? Yes, video games, for some reason.

CHUCK TODD (MSNBC): Can you envision a way of supporting the universal background checks bill?

LAMAR ALEXANDER: Chuck, I'm going to wait and see on all of these bills. I think video games is [sic] a bigger problem than guns, because video games affect people. But the First Amendment limits what we can do about video games, and the Second Amendment to the Constitution limits what we can do about guns.

Concerns about video game violence have been twinned to concerns about gun violence from as far back as the Columbine shooting, when pundits fussed and fretted over how Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold enjoyed yesteryear's most popular first-person shooter, "Doom." (Also, they were vaguely "goth," according to observers, which for a time made life hard for Bauhaus fans who just wanted to be alone and sad and misunderstood.) I was never too convinced by the argument: Video games, unlike the act of shooting up an entire school of children, were and remain popular, with hundreds of thousands millions of people partaking in the escape. That some mass-murderers occasionally participated in that culture seems to be incidental at best -- a tiny bit of statistical effluvia that should be written off as insignificant at the outset.

"Video games affect people," of course, is not actually an argument. Monet paintings affect people. Long waits at the DMV affect people. If there's anything that diminishes my worry about whether or not Alexander will seriously consider the prospect of beefing up background checks, it would be the way that this thought sort of floated out of him like flatulence, unattached to anything serious. If I could assure Alexander of anything, however, I would point out that we have spared no expense in trying to ascertain the ways in which video games affect people, up to and including whether they can be connected to violent tendencies in real life.

Historically, it's been a hard case to make. I can point you immediately to this article from the Washington Post's Max Fischer, in which he runs down the statistics on the 10 largest global markets for video games and finds "no evident, statistical correlation between video game consumption and gun-related killings."

It's true that Americans spend billions of dollars on video games every year and that the United States has the highest firearm murder rate in the developed world. But other countries where video games are popular have much lower firearm-related murder rates. In fact, countries where video game consumption is highest tend to be some of the safest countries in the world, likely a product of the fact that developed or rich countries, where consumers can afford expensive games, have on average much less violent crime.

But there's no reason to stop there. Over at Kotaku, Jason Schreier has a lengthy piece about the past quarter century of research into video games and their connection to violence or, as it's more popularly termed, "aggression." Schreier gives the matter a thorough going-over, presenting the case for concern alongside the case against. It's absolutely fair to say that some studies have ended with the conclusion that a correlation between violence and video games exists. But it's also fair to say that many have not. Nevertheless Schreier gives serious, scholarly consideration to the matter, and so I'd urge people to go read the whole thing.

For the time being, however, here's the key data point: "The first major violent video game study took place in 1984." Yes, that's right, we are approaching the 30th anniversary of considering the impact of a globally popular entertainment medium on mass shootings in the U.S. And as Schreier points out, a sizable infrastructure has grown to support this never-ending research.

One factor worth considering: who funds all of these studies?

"Some scholars have taken research funding from advocacy groups, which is just as bad as taking research funding from the video game industry, as far as I'm concerned," said Ferguson, pointing to groups like the now-defunct National Institute on Media and the Family and the Center For Successful Parenting, a family-values group that sets out to find the negative effects in violent media.

"It's something we need to stop on both sides."

...

And what of the video game industry? I reached out to Dan Hewitt, a representative for the Entertainment Software Association (the group that helps regulate and represent gaming companies), to ask.

"ESA hasn't funded any research in any way," Hewitt told me in an e-mail. "Everything that's out there and that we talk about is completely free from any ESA influence or financing."

Ultimately, I reach a different conclusion than Scheier: I find this all to be a bit boondoggle-y, while he contends that "it's hard to argue with Obama's assertion that we need more research into the effects of violent video games."

Oh, that's right. We're going to spend another bag of ducats re-studying this anyway. So in the end, Alexander is getting his wish.

Speaking for myself, I believe that law-abiding citizens are law-abiding citizens, and I'm unaccustomed to demonizing them. Moreover, I think we're not as far ahead on solving this problem as we could be, because the well has long been poisoned by people who have demonized gun owners who have done nothing wrong. I'm very amenable to the argument that we should not pick on the lowest common denominator in this debate, and I hope that my antipathy to high-capacity magazines and my worry about military-style arms being in public circulation can stand alongside these sentiments. I think that the fact that 75 percent of NRA members agree that strengthening the background check system is a worthwhile policy to pursue goes a long way to proving that it doesn't go after the lowest common denominator, and I certainly think that it doesn't.

But let's not trade the pointless demonization of law-abiding gun owners for the pointless demonization of law-abiding video game enthusiasts. Gamers are not saints, and there are certainly aspects to gamer culture that disturb me. (Just ask Anita Sarkeesian.) But the simple fact of the matter is that nobody becomes more materially dangerous to society by dint of owning a Playstation. And I'd rather face down someone armed with a copy of "Call Of Duty" than someone armed with a Sig Sauer any day of the week.

Original Article

Source: huffington post

Author: Jason Linkins

No comments:

Post a Comment