"Where they burn books, eventually they will burn people."

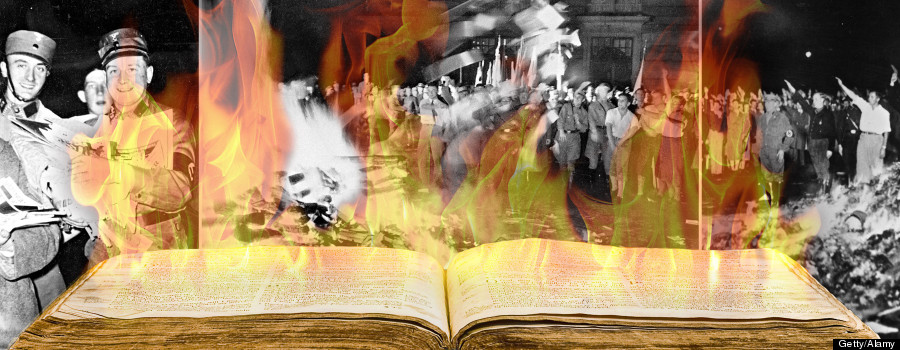

Today marks 80 years since the mass burnings of books written by Jewish, communist and pacifist authors across university towns in Germany.

Heinrich Heine could have written those words to describe the Nazi ascent to power. In fact, they appeared more than a century before Adolf Hitler became German Chancellor, but they are now engraved on the site of the mass Nazi student burnings of books on Berlin's Opernplatz.

In 2013, Heine's sentiment is still as relevant, especially if you consider their context in Heine's 1821 play Almansor, the line actually refers to the burning of a Koran.

Book burning, for cultural, religious or intellectual reasons, is one of the final taboos, a base act of desecration. It is more than turning ink and paper to ash, but to show contempt for thought, to stifle dissent.

Even eighty years since the Nazi book burnings, as printed books are threatened not by flames but by advanced technology, burning a book can cause the most visceral of emotional reactions.

In 2010 there was world-wide outcry as Pastor Terry Jones launched the 'Burn A Koran Day', announcing his intention to burn 200 copies of the holy Islamic text on the anniversary of 9/11.

Often the motive has been religious, Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses was ceremonially burned in Bolton and Bradford in 1988; in 2006 Conservative Italian councillors in Rome burned The Da Vinci Code, and even when US soldiers accidentally burnt copies of the Koran in Afghanistan last year, they came close to causing a major international incident.

"It is shocking because it breaks all the boundaries of civilisation, it is the destruction of knowledge, it is a contempt for art, for literature, which we find deeply repugnant," Professor Sir Richard Evans, president of Wolfson College, Cambridge told HuffPostUK.

Dr Nadine Rossol, from the University of Essex's history department, said she considers the impact of the 1933 book burnings to be largely historic, more poignant because we now know what was to come. "The impact is was not so much the event at the time, although it was covered in international news reports at the time, but because we know what came afterwards.

"So looking back at the book burning it acquires most of its meaning from our knowledge of the events that followed - the assumption that burning books, and symbolically killing intellectual activities and freedom, will eventually lead to burning people.

"We like straight stories and this fits nicely to what the Nazis actually did and therefore it has become a symbol for these developments. For a general public, it is much less used to link it to persecution and restrictions of authors, academics, intellectuals, artists and their difficulties to continue their work, to conform, if they stayed in Germany, to National Socialist principles regarding cultural policy and knowledge production."

Even though book burnings had taken place before in Europe, notably during the Spanish Inquisition when 5,000 Arabic manuscripts were burned in Granada in 1499, Professor Evans called the Nazi burnings "a unique phenomena, to receive so much publicity, to be so organised, to be such a public ceremony. The Americans burnt books by William Reich in the 1950s, but never in public."

In Berlin, on May 10 1933, more than 40,000 gathered to watch the burnings, and it was an atmosphere of celebration in 19 different towns, co-ordinated by the German Student Association. More than 25,000 books from university and public libraries were set a-flame.

Those decreed "Un-German" included playwright Bertolt Brecht, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, Karl Marx, HG Wells and Heinrich Heine himself.

Professor Evans said that the history behind the burnings was "widely misunderstood.The national student movement had been taken over by Nazi students, who were running a very radical campaign to Nazi-fy the universities, obstructing lectures by progressive and left-wing professors, occupying student buildings demanding the removal of certain professors, they wanted a formal role in appointing professors, taking books out of libraries.

"This particular book-burning day was called "The Act against the Un-German Spirit". The newsreel pictures show Goebbels at the event, but he was there by invitation, he was not the organiser.

"Goebbels praised the act, but Nazis acted pretty quickly after that to clamp down on the students. They banned them from removing anymore books. They wanted to set up a pillory for un-German professors' publications to be nailed to in the town squares, but the Nazi Education Ministry put a stop to it.

"The Nazis were more interested in installing Nazi professors into universities, putting them in charge. But no student was disciplined, even though it was implied they should keep order in future."

Scientists, architects, university professors, "all the scientific excellence that before 1933 brought Germany its many Nobel Prizes," escaped Germany, historian Werner Tress of the Centre for European-Jewish Studies in Potsdam told France 24. "Since then, it has never managed to recover the rank it held before 1933."

But can the act of burning books ever be reclaimed as an act of defiance against those who would destroy ideas?

Shaun Bythell, who runs The Bookshop in Wigtown, Scotland, attempted to prove just that in 2005 by staging a mass burning of unwanted books in his home town. "It was mainly a publicity stunt," he admits, "but also to make people aware that books are not permanent objects, they break, they get thrown out.

"There's a sanctity attached to books, in reality it is just another object. People have quite an unintelligent impetus to protect the book itself.

"Anyone who has tried to burn books to wipe out ideologies has always failed. It is a pointless exercise. Ideas exist beyond the book. You are ridiculing the idea that you can destroy ideas by burning books. You can't.

"There's a gap in the logic of those who say that you can't burn books because the Nazis burned books, or Genghis Khan burnt books. The Nazis ran the trains on time, but a train arriving on time in the UK doesn't mean it's being driven by a Nazi. Not that many trains arrive on time in the UK."

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.co.uk

Author: Jessica Elgot

Today marks 80 years since the mass burnings of books written by Jewish, communist and pacifist authors across university towns in Germany.

Heinrich Heine could have written those words to describe the Nazi ascent to power. In fact, they appeared more than a century before Adolf Hitler became German Chancellor, but they are now engraved on the site of the mass Nazi student burnings of books on Berlin's Opernplatz.

In 2013, Heine's sentiment is still as relevant, especially if you consider their context in Heine's 1821 play Almansor, the line actually refers to the burning of a Koran.

Book burning, for cultural, religious or intellectual reasons, is one of the final taboos, a base act of desecration. It is more than turning ink and paper to ash, but to show contempt for thought, to stifle dissent.

Even eighty years since the Nazi book burnings, as printed books are threatened not by flames but by advanced technology, burning a book can cause the most visceral of emotional reactions.

In 2010 there was world-wide outcry as Pastor Terry Jones launched the 'Burn A Koran Day', announcing his intention to burn 200 copies of the holy Islamic text on the anniversary of 9/11.

Often the motive has been religious, Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses was ceremonially burned in Bolton and Bradford in 1988; in 2006 Conservative Italian councillors in Rome burned The Da Vinci Code, and even when US soldiers accidentally burnt copies of the Koran in Afghanistan last year, they came close to causing a major international incident.

"It is shocking because it breaks all the boundaries of civilisation, it is the destruction of knowledge, it is a contempt for art, for literature, which we find deeply repugnant," Professor Sir Richard Evans, president of Wolfson College, Cambridge told HuffPostUK.

Dr Nadine Rossol, from the University of Essex's history department, said she considers the impact of the 1933 book burnings to be largely historic, more poignant because we now know what was to come. "The impact is was not so much the event at the time, although it was covered in international news reports at the time, but because we know what came afterwards.

"So looking back at the book burning it acquires most of its meaning from our knowledge of the events that followed - the assumption that burning books, and symbolically killing intellectual activities and freedom, will eventually lead to burning people.

"We like straight stories and this fits nicely to what the Nazis actually did and therefore it has become a symbol for these developments. For a general public, it is much less used to link it to persecution and restrictions of authors, academics, intellectuals, artists and their difficulties to continue their work, to conform, if they stayed in Germany, to National Socialist principles regarding cultural policy and knowledge production."

Even though book burnings had taken place before in Europe, notably during the Spanish Inquisition when 5,000 Arabic manuscripts were burned in Granada in 1499, Professor Evans called the Nazi burnings "a unique phenomena, to receive so much publicity, to be so organised, to be such a public ceremony. The Americans burnt books by William Reich in the 1950s, but never in public."

In Berlin, on May 10 1933, more than 40,000 gathered to watch the burnings, and it was an atmosphere of celebration in 19 different towns, co-ordinated by the German Student Association. More than 25,000 books from university and public libraries were set a-flame.

Those decreed "Un-German" included playwright Bertolt Brecht, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, Karl Marx, HG Wells and Heinrich Heine himself.

Professor Evans said that the history behind the burnings was "widely misunderstood.The national student movement had been taken over by Nazi students, who were running a very radical campaign to Nazi-fy the universities, obstructing lectures by progressive and left-wing professors, occupying student buildings demanding the removal of certain professors, they wanted a formal role in appointing professors, taking books out of libraries.

"This particular book-burning day was called "The Act against the Un-German Spirit". The newsreel pictures show Goebbels at the event, but he was there by invitation, he was not the organiser.

"Goebbels praised the act, but Nazis acted pretty quickly after that to clamp down on the students. They banned them from removing anymore books. They wanted to set up a pillory for un-German professors' publications to be nailed to in the town squares, but the Nazi Education Ministry put a stop to it.

"The Nazis were more interested in installing Nazi professors into universities, putting them in charge. But no student was disciplined, even though it was implied they should keep order in future."

Scientists, architects, university professors, "all the scientific excellence that before 1933 brought Germany its many Nobel Prizes," escaped Germany, historian Werner Tress of the Centre for European-Jewish Studies in Potsdam told France 24. "Since then, it has never managed to recover the rank it held before 1933."

But can the act of burning books ever be reclaimed as an act of defiance against those who would destroy ideas?

Shaun Bythell, who runs The Bookshop in Wigtown, Scotland, attempted to prove just that in 2005 by staging a mass burning of unwanted books in his home town. "It was mainly a publicity stunt," he admits, "but also to make people aware that books are not permanent objects, they break, they get thrown out.

"There's a sanctity attached to books, in reality it is just another object. People have quite an unintelligent impetus to protect the book itself.

"Anyone who has tried to burn books to wipe out ideologies has always failed. It is a pointless exercise. Ideas exist beyond the book. You are ridiculing the idea that you can destroy ideas by burning books. You can't.

"There's a gap in the logic of those who say that you can't burn books because the Nazis burned books, or Genghis Khan burnt books. The Nazis ran the trains on time, but a train arriving on time in the UK doesn't mean it's being driven by a Nazi. Not that many trains arrive on time in the UK."

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.co.uk

Author: Jessica Elgot

No comments:

Post a Comment