NEW ORLEANS -- Some questions seem particularly prone to set John Thompson off. Here's one he gets a lot: Have the prosecutors who sent him to death row ever apologized?

"Sorry? For what?" says Thompson. The 49-year-old is lean, almost skinny. He wears jeans, a T-shirt and running shoes and sports a thin mustache and soul patch, both stippled with gray. "You tell me that. Tell me what the hell would they be sorry for. They tried to kill me. To apologize would mean they're admitting the system is broken." His voice has been gradually increasing in volume. He's nearly yelling now. "That everyone around them is broken. It's the same motherfucking system that's protecting them."

He paces as he talks. His voice soars and breaks. At times, he gets within a few inches of me, jabbing his finger in my direction for emphasis. Thompson pauses as he takes a phone call from his wife. His tone changes for the duration of the conversation. Then he hangs up and resumes with the indignation. "What would I do with their apology anyway? Sorry. Huh. Sorry you tried to kill me? Sorry you tried to commit premeditated murder? No. No thank you. I don't need your apology."

The wrongly convicted often show remarkable grace and humility. It's inspiring to see, if a little difficult to understand; even after years or decades in prison, exonerees are typically marked by an absence of bitterness.

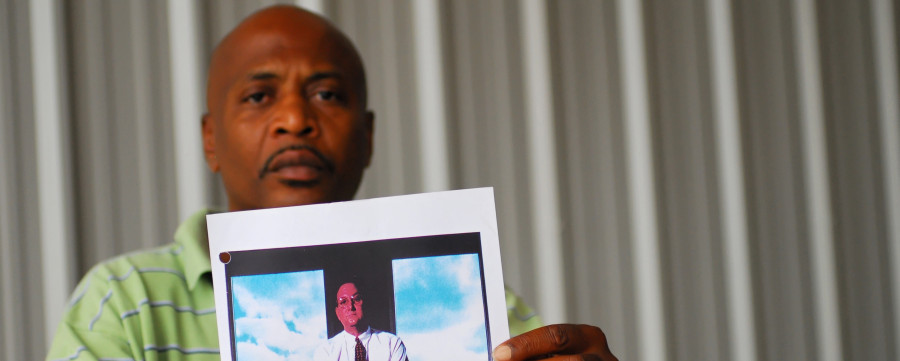

Not Thompson, but you can hardly blame him. Even among outrageous false conviction stories, his tale is particularly brutal. He was wrongly convicted not once, but twice -- separately -- for a carjacking and a murder. He spent 18 years at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, 14 of them on death row. His death warrant was signed eight times. When his attorneys finally found the evidence that cleared him -- evidence his prosecutors had known about for years -- he was weeks away from execution.

But what most enrages Thompson -- and what drives his activism today -- is that in the end, there was no accountability. His case produced a surfeit of prosecutorial malfeasance, from incompetence, to poor training, to a culture of conviction that included both willfully ignoring evidence that could have led to his exoneration, to blatantly withholding it. Yet the only attorney ever disciplined in his case was a former prosecutor who eventually aided in Thompson's defense.

"This isn't about bad men, though they were most assuredly bad men," Thompson says. "It's about a system that is void of integrity. Mistakes can happen. But if you don't do anything to stop them from happening again, you can't keep calling them mistakes."

Over the last year or so, a number of high-profile stories have fostered discussion and analysis of prosecutorial power, discretion and accountability: the prosecution and subsequent suicide of Internet activist Aaron Swartz; the Obama administration's unprecedented prosecution of whistleblowers; the related Department of Justice investigations into the sources of leaks that have raised First Amendment concerns; and aggressive prosecutions that look politically motivated, such as the pursuit of medical marijuana offenders in states where the drug has been legalized for that purpose. In May, an 82-year-old nun and two other peace activists were convicted of "sabotage" and other "crimes of violence" for breaking into a nuclear weapons plant to unfurl banners, spray paint and sing hymns. Even many on the political right, traditionally a source of law-and-order-minded support for prosecutors, have raised concerns about "overcriminalization" and the corresponding power the trend has given prosecutors.

Most recently, the Justice Department came under fire for its investigation of leaks to the media, including a broad subpoena for phone records of the Associated Press, and for obtaining the phone and email records of Fox News reporter James Rosen. In the Rosen case, Attorney General Eric Holder personally signed off on a warrant that claimed that merely publishing information that had been leaked to him made Rosen a criminal co-conspirator. Many have pointed out that such a charge would make it a crime to practice journalism.

President Obama has since expressed his dismay at the Rosen warrant, but his response was curious. He asked Holder to investigate the possible misconduct that not only occurred under Holder's supervision, but in which Holder himself may have participated.

In asking Eric Holder to investigate Eric Holder, Obama illustrated the difficulty of adequately addressing prosecutorial misconduct as well as anyone possibly could: Prosecutors are relied upon to police themselves, and it isn't working. A growing chorus of voices in the legal community says the problem is rooted in a culture of infallibility, from Holder on down. And it's against this backdrop -- this environment of legal invincibility -- that we get the revelations of massive data collection by the National Security Agency, government employees who lie to Congress with no repercussions, and government investigators, courts and prosecutors operating in secret.

In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed Thompson's lawsuit against Orleans Parish and the office of former District Attorney Harry Connick (father of the debonair crooner). The court's decision in Connick v. Thompson added yet another layer of protection for aggressive prosecutors, in this instance by making it more difficult to sue the governments that employ them. It was just the latest in a series of Supreme Court decisions going back to the 1970s that have insulated prosecutors from any real consequences of their actions.

Prosecutors and their advocates say complete and absolute immunity from civil liability is critical to the performance of their jobs. They argue that self-regulation and professional sanctions from state bar associations are sufficient to deter misconduct. Yet there's little evidence that state bar associations are doing anything to police prosecutors, and numerous studies have shown that those who misbehave are rarely if ever professionally disciplined.

And in a culture where racking up convictions tends to win prosecutors promotions, elevation to higher office and high-paying gigs with white-shoe law firms, civil liberties activists and advocates for criminal justice reform worry there's no countervailing force to hold overzealous prosecutors to their ethical obligations.

In the end, one of the most powerful positions in public service -- a position that carries with it the authority not only to ruin lives, but in many cases the power to end them -- is one of the positions most shielded from liability and accountability. And the freedom to push ahead free of consequences has created a zealous conviction culture.

Nowhere is the ethos of impunity more apparent than in Louisiana and in Orleans Parish, the site of Thompson's case. The Louisiana Supreme Court, which must give final approval to any disciplinary action taken against a prosecutor in the state, didn't impose its first professional sanction on any prosecutor until 2005. According to Charles Plattsmier, who heads the state's Office of Disciplinary Counsel, only two prosecutors have been disciplined since -- despite dozens of exonerations since the 1990s, a large share of which came in part or entirely due to prosecutorial misconduct.

Since the Supreme Court issued its decision in Connick v. Thompson in March 2011, several defense attorneys in New Orleans have responded by filing complaints against the city's prosecutors. Leading the charge is Sam Dalton, a legal legend in New Orleans who has practiced criminal defense law in the area for 60 years. According to Dalton and others, not only have these recent complaints not been investigated, in some cases they have yet to hear receipt of confirmation months after they were filed. Even the head of the board concedes that significant barriers to accountability persist.

Thompson is certainly aware of that. "These people tried to eliminate me from the face of the earth," Thompson says of his own prosecutors. "Do you get that? They tried to murder me. And goddamnit, there have to be some kind of consequences."

THE PROSECUTOR'S BUBBLE

There are a number of ways for a prosecutor to commit misconduct. He could make inappropriate comments to jurors, or coax witnesses into giving false or misleading testimony. But one of the most pervasive misdeeds is the Brady violation, or the failure to turn over favorable evidence to the defendant. It's the most common form of misconduct cited by courts in overturning convictions.

The name refers to the 50-year-old Supreme Court decision in Brady v. Maryland, which required prosecutors to divulge such information, like deals made with state's witnesses, crime scene evidence that could be tested for DNA, information that could discredit a state's witness and portions of police reports that could be favorable to the defendant. But there's very little to hold prosecutors to the Brady obligation.

Courts most commonly deal with misconduct by overturning convictions. To get a new trial, however, a defendant must not only show evidence of prosecutorial misconduct, but must also show that without that misconduct the jury likely would have acquitted.

The policy may seem more sensible than one of setting guilty people free because of low-level prosecutorial misconduct that had no impact on the verdict, but civil liberties advocates say it sets the bar too high. "It requires appellate court judges to sit as jurors," says Steven Benjamin, president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. "It puts them in a role they were never intended to be in, and asks them to retroactively put themselves at trials they didn't attend. It takes a really extreme case to overturn a conviction."

Moreover, throwing out a conviction is intended to ensure due process for a given defendant -- not to punish a wayward prosecutor. Appellate court decisions that overturn convictions due to prosecutorial misconduct rarely even mention the offending prosecutor by name.

At the other end of the severity scale, someone could bring criminal charges against a misbehaving prosecutor. But this is vanishingly rare. While there's no authoritative count of the number of times it's happened, a 2011 Yale Law Journal article surveying the use of misconduct sanctions found that the first such case to reach a verdict in the U.S. was in 1999. (The jury acquitted.) More recently, the 2006 Duke lacrosse case resulted in criminal contempt charges against Durham County District Attorney Mike Nifong. He was disbarred and sentenced to a day in jail.

Former Williamson County, Texas, District Attorney Ken Anderson currently faces felony charges for failure to turn over exculpatory evidence in the case of Michael Morton, a man who served 25 years in prison for his wife's murder until he was exonerated by DNA testing on evidence Anderson allegedly had helped cover up.

The charges against Nifong and Anderson are newsworthy precisely because they're so uncommon. "The situation in Texas is encouraging, but I can't think of any other examples beyond that one and the Duke case," Benjamin says.

In 2008, Craig Watkins, the district attorney in Dallas County, Texas, suggested that both criminal charges and disbarment for willful Brady violations should be more common. The mere utterance of such a thing from a sitting prosecutor was unexpected, even from a DA like Watkins, a former defense attorney who has been widely praised for his efforts to reform the culture in the Dallas DA's office. The New York defense attorney and popular law blogger Scott Greenfield called it "earth-shattering."

Yet Watkins's suggestion glosses over the fact any such charges would need to be brought by another prosecutor, likely a state attorney general. Even if state legislatures were to formally criminalize Brady violations, it seems unlikely that many prosecutors or state attorneys general would pursue charges against their colleagues, and certainly not enough to make criminal charges an effective deterrent.

The federal government could also bring criminal civil rights charges against prosecutors who knowingly withhold exculpatory evidence. But this is also exceedingly rare. Bennett Gershman, who studies prosecutorial misconduct at Pace University Law School, could cite only one instance in which it has happened: the federal government's pursuit of charges against former federal prosecutor Richard Convertino for withholding exculpatory evidence in a terrorism case he prosecuted shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. Convertino was acquitted.

Suing prosecutors whose misconduct contributes to wrongful convictions is even more difficult. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled out torts law as an option for plaintiffs nearly a century ago. And in the 1976 case Imbler v. Pachtman, the court ruled that under federal civil rights law, prosecutors also enjoy absolute immunity from any lawsuit over any action undertaken as a prosecutor. The court later extended this personal immunity to cover supervisory prosecutors who fail to properly train their subordinates.

Now even a prosecutor who knowingly submits false evidence in a case that results in the wrongful conviction -- or even the execution -- of an innocent person can't be personally sued for damages. The only way a prosecutor can be sued under present law is if she was acting as an investigator in a police role -- duties above and beyond those of a prosecutor -- at the time she violated the defendant's civil rights. But even here, prosecutors enjoy the qualified immunity afforded to police officers: A plaintiff must still show a willful violation of well-established constitutional rights to even get in front of a jury.

The 2009 Supreme Court case Pottawattamie v. McGhee shows how absurd the logic behind prosecutorial immunity can get. Prosecutors were found to have fabricated evidence to help them convict two innocent men, Terry Harrington and Curtis McGhee, who between them spent more than 50 years in prison. Attorneys for the prosecutors, along with the Office of the Solicitor General and several state attorneys general, argued they should be immune from any liability. They said that while the prosecutors may have been acting as police investigators when they fabricated the evidence, the actual injury occurred only when the jury wrongly convicted Harrington and McGhee. It followed that because the prosecutors were acting as prosecutors when the injury occurred, they were still shielded by absolute immunity. Deputy Solicitor General Neal Katyal even argued to the court that there is no "free-standing due process right not to be framed."

During oral arguments in the case, Justice Anthony Kennedy summed up this defense less than sympathetically: "The more deeply you're involved in the wrong, the more likely you are to be immune." And there was at least some indication during the oral arguments that some justices were moving toward limiting prosecutorial immunity.

But before the court could rule, Pottawattamie County settled with Harrington and McGhee. For now, the question of whether a prosecutor can be held personally liable for knowingly manufacturing evidence to convict an innocent person remains unsettled.

John Thompson's case dealt with the issue of municipal liability. He couldn't sue any of the prosecutors personally, but in theory, he could still go to federal court to sue the city or county where the prosecutors worked.

But simply being wronged by a rogue prosecutor isn't enough. He would also have to show that employees of the government entity he was suing routinely committed similar civil rights violations; that these violations were the result of a policy, pattern or practice endorsed by the city or county; and that the prosecutor's actions were a direct consequence of those policies and practices.

That's a lot to prove, but municipal liability could bring some justice to people wronged by a flawed system. And if such lawsuits result in large awards, perhaps they could begin to apply some political pressure to policymakers and public officials to change their ways.

But here, too, the federal courts have built a formidable legal moat around recompense for the wrongly imprisoned -- and around indirect accountability for the prosecutors who put them away. Since 1976, only a narrow theory of municipal liability and the possibility of professional sanction remain as viable avenues to hold prosecutors accountable. And in an era where the prevailing criminal justice climate has been to find more ways to fill more prisons as quickly as possible, neither has done much of anything to deter misconduct.

That's generally true across the country, and it's particularly true in Orleans Parish.

A TRADITION OF INDIFFERENCE

In 1985, John Thompson was convicted of two felonies; first for the armed robbery of a university student and two others, then three weeks later for the murder of Raymond T. Liuzza, Jr. The armed robbery conviction kept Thompson from testifying on his own behalf at his murder trial -- doing so would have allowed prosecutors to bring up the other conviction in front of the jury. So he was convicted for the murder, too. For the next 14 years, Thompson fought both convictions, eventually with the assistance of attorneys at Loyola University's Capital Defense Project and Gordon Cooney and Michael Banks, both attorneys at Morgan and Lewis, a corporate law firm in Philadelphia.

Thompson was up against a prosecutorial climate that critics had long claimed valued convictions over all else, one that saw a death sentence as the profession's brass ring. The New York Times reported in 2003 that prosecutors in Louisiana often threw parties after winning death sentences. They gave one another informal awards for murder convictions, including plaques with hypodermic needles bearing the names of the convicted. In Jefferson Parish, just outside of New Orleans, some wore neckties decorated with images of nooses or the Grim Reaper.

One of Thompson's prosecutors, Assistant District Attorney James Williams, told the the Los Angeles Times in 2007, "There was no thrill for me unless there was a chance for the death penalty."

Williams kept a replica electric chair on his desk. "It was hooked up to a battery, so you'd get a little jolt when you touched it," recalls Michael Banks, one of Thompson's attorneys. In 1995, Williams posed with this mini-execution chair in Esquire magazine. On the chair's headboard, he had affixed the photos of the five men he had sent to death row, including Thompson. Of those five, two would later be exonerated and two more would have their sentences commuted.

By 1999, Thompson had already forestalled seven death warrants, and was staring down number eight. He had exhausted most of his legal options, and was just weeks from execution. In a last-ditch effort to save him, a defense investigator went combing through old records at a New Orleans police station and came across the microfiche file that would save Thompson's life.

The file held the results of a blood test performed on a swatch of clothing taken from one of the victims of the armed robbery for which Thompson was convicted. The blood on the cloth belonged to the perpetrator. The swatch of clothing itself has never been found, but according to the test results, the armed robber's blood was type B. Thompson's is type O.

Thompson's death sentence was vacated, the armed robbery conviction was eventually thrown out and he was granted a new trial for Liuzza's murder. His attorneys were able to show that prosecutors had withheld exculpatory evidence at Thompson's first murder trial, too, including an eyewitness description of Luizza's killer from the key prosecution witness who implicated Thompson. In the new trial, Thompson was also able testify and give his alibi. It took the jury 35 minutes to acquit him.

When the buried blood test was first made public in late April 1999, Harry Connick, the Orleans Parish district attorney, called a press conference. He announced an internal investigation, to be led by Assistant District Attorney Jerry Glas. A week later, Glas resigned.

During a deposition at Thompson's civil trial, Glas gave the reason for his resignation. He believed Williams, the prosecutor, knew about the swatch of clothing and the blood test, but had concealed the test and may have helped destroy the blood sample. He also believed the other prosecutors in the case -- Assistant District Attorneys Eric Dubelier and Gerry Deegan -- may have been implicated. Glas recommended that Williams be indicted, and he wanted more time to investigate Dubelier. Deegan had since passed away, but in a sworn deposition, another former prosecutor said that on his deathbed, Deegan had told of the existence of the exonerating cloth and blood test, and admitted that he had helped to hide it. Glas revealed all of this to Connick in May 1999, along with his plan to present it to the grand jury. Connick promptly closed down the grand jury, and Glas resigned.

By the time Thompson filed his misconduct lawsuit against Orleans Parish in 2005, another wrongly convicted New Orleans man had already filed a similar suit and come up short. Shareef Cousin was convicted in 1996 for the 1995 murder of Michael Gerardi, who was shot and killed in front of his date, Connie Babin, just after the two had eaten dinner in the French Quarter. Babin would later claim she was "absolutely positive" that Cousin, who was 16 at the time, was Gerardi's killer.

Cousin's trial produced one particularly odious example of misconduct. The prosecution called on James Rowel, a friend of Cousin's. They expected him to testify that Cousin had confessed the murder to him. Instead, to the surprise of everyone, Rowel denied Cousin had ever confessed. Instead, he informed the courtroom that prosecutors had promised him leniency on his own pending charges if he would falsely implicate his friend.

Connick's prosecutors attempted an awkward correction by calling a police officer and Rowel's former attorney to the stand, both of whom claimed that Rowel had told prosecutors about the confession of his own volition. The prosecutors then attempted to submit that testimony to jurors as substantive evidence of Cousin's guilt. It was a move the Louisiana Supreme Court later called "a flagrant misuse" of evidence.

Cousin also had an alibi: He was playing in an organized basketball game at the time of the murder. He had video evidence, plus testimony from two Parks and Recreation supervisors, an opposing player and his coach that put him on the basketball court when Gerardi was murdered. The jury convicted him anyway, and sentenced him to death.

During Cousin's appeal, his attorneys discovered more misconduct. Assistant District Attorney Roger Jordan had suppressed statements from Babin that cast serious doubt on her testimony. Prior to her "absolutely certain" claim, Babin had told police that she hadn't gotten a good look at the gunman, and that she wasn't wearing her contact lenses at the time of the attack. Without her prescription lenses, she said, she could only see "shapes and patterns." At some point between the time she made those statements to police and her trial testimony, Babin had somehow grown increasingly sure about Cousin. The Louisiana Supreme Court overturned Cousin's conviction in 1998, and Connick's office declined to try him again.

Like John Thompson's, Cousin's murder defense was complicated by the fact that Orleans Parish prosecutors were simultaneously pursuing other charges against him for unrelated crimes -- in his case, four armed robberies.

"My attorney told me that the prosecutors were going to try each of the robberies separately," Cousin recalls. "I didn't do them. But he told me there was no way we could beat four armed robbery charges and also win the murder case. He said we needed to focus on the murder. So I pled guilty to the robberies. I wish I hadn't. But I was 16. I was a child. You do what your attorney tells you to do."

Because of the robbery convictions, Cousin remained in prison until 2007. But he filed his lawsuit in 2000, from prison, hoping to collect under both municipal and personal liability. Cousin first alleged that the Orleans Parish DA's office was mired in a culture of prosecutorial misconduct, which had been created by policies and practices set by Connick. He also attempted to hold prosecutors personally liable under the narrow exception from absolute immunity permitted when prosecutors act as investigators.

In March 2003, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit rejected all of Cousin's claims. On the exception to absolute immunity, the court found that once police had identified Cousin as a suspect, there was a strong presumption that everything the prosecutors did going forward they did in the role of prosecutors preparing for trial, not as investigators attempting to solve a crime.

It was arguably the correct outcome under the law, given the precedents already set by the U.S. Supreme Court. But the specifics of the Fifth Circuit Court's opinion show just how unfairly those precedents can play out. The court ruled that even if prosecutors had intimidated and coerced James Rowel into lying on the witness stand, they clearly did so in their role as prosecutors, not as investigators, and were therefore immune from liability. The court said the same thing about allegations that prosecutors lied about Babin's initial statements, and about Cousin's contention that prosecutors buried evidence pointing to other suspects.

One particularly explosive allegation from Cousin was that Connick's office had trumped up charges and illegally detained witnesses whom Cousin had planned to call to testify in his defense, which not only violated the rights of those witnesses, but also made it impossible for Cousin's attorneys to find them so that they could testify. The court acknowledged that if true, this would be an egregious and malicious example of misconduct. But because it was done in pursuit of Cousin's conviction, it was still "prosecutorial in nature, and therefore shielded by absolute immunity."

The court then turned to Cousin's other hope to collect: his argument that the policies and practices in Connick's office had created a culture of indifference about disclosing exculpatory evidence. Despite the dozen-plus cases of misconduct cited by Cousin's attorneys, the court ruled against him. According to the opinion, Cousin's "citation to a small number of cases, out of thousands handled over twenty-five years" wasn't enough to show a pattern or practice of deliberate indifference.

That analysis is likely flawed. "A Brady violation is by definition a cover-up," says Banks, the attorney for Thompson. "So we only know about the violations that have been exposed."

Emily Maw, director of the New Orleans Innocence Project, a group that advocates for the wrongfully convicted, says violations in low-level cases are much less likely to come to light. "It's expensive to discover a Brady violation. They're usually found after conviction, with the help of investigators and attorneys poring through police reports and prosecutors' files."

In fact, because Brady violations are suppressions of evidence, they're only likely to come to light once a defendant is given full access to the state's complete case file. In Louisiana, that only happens after conviction. Moreover, the only defendants who have the right to a state-provided attorney after conviction are those who are facing the death penalty. Indigent defendants sentenced to life or less must find pro bono help, or they're on their own.

This means that the only convictions systematically vetted for Brady violations in Louisiana are death penalty cases. And here, the numbers are quite a bit more alarming. Between 1973 and 2002, Orleans Parish prosecutors sent 36 people to death row. Nine of those convictions were later overturned due to Brady violations. Four of those later resulted in exonerations. In other words, 11 percent of the men Connick's office attempted to send to their deaths -- for which prosecutors suppressed exculpatory evidence in the process -- were later found to be factually innocent.

Over the years, even some of the judges in Orleans Parish had expressed concern about the culture in Connick's office. In a 2011 brief (PDF) to the U.S. Supreme Court, the attorneys for another murder defendant named Juan Smith cited press accounts going back to the 1990s describing judges that were "increasingly impatient with what they say are clear violations of discovery laws by prosecutors." One article reported that judges had "voiced their dismay" over an "active unwillingness to follow the rule of law." Some judges had even ordered prosecutors to take legal classes. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned Smith's conviction (PDF) just last year, again because of Brady violations.

The U.S. Supreme Court had already rebuked Connick's office for its culture of misconduct. In the 1995 case Kyles v. Whitley, Justice David Souter's majority opinion scolded Orleans prosecutors for "blatant and repeated violations" of Brady, and described a culture that had "descend[ed] to a gladiatorial level unmitigated by any prosecutorial obligation for the sake of the truth."

None of this was enough to convince the Fifth Circuit to find a pattern of unconstitutional behavior in Cousin's case. In the end, the Fifth Circuit opinion suggests that the status quo in Orleans Parish and elsewhere is perfectly adequate: "Where prosecutors commit Brady violations, convictions may be overturned. That could be a sufficient deterrent, so that the imposition of additional sanctions ... is unnecessary."

John Thompson filed his lawsuit against Orleans Parish and his prosecutors in 2005, two years after Cousin had been denied. "We were pretty limited by that decision," Banks recalls. "We could have tried again, and there were even more examples of misconduct we could have used, but we didn't want to risk having the court refer back to that decision and dismiss us out of hand."

Instead, Thompson's attorneys decided to pursue another possible opening to municipal liability. In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court suggested that a single incident of a civil rights violation could be so grievous that it could give rise to a lawsuit on its own. As an example, the court theorized a police shooting in a city that employed an armed police department, but didn't bother to train its officers in the use of lethal force.

Thompson's attorneys argued that the violation in his case, and Connick's failure to train his staff in Brady requirements, was egregious enough to qualify as such an event. But it was a narrow argument that barred Thompson from bringing up all the violations Connick's office had committed in other cases.

Thompson was still able to present ample evidence of indifference -- even hostility -- to the Brady requirement. For example, after being chastised by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Kyles case in 1995, Connick said he saw "no need" to make any changes to his office policy. In depositions, Connick claimed he wasn't even aware of the fact that the court had ruled against him in Kyles. He also testified that he had stopped reading law books and legal opinions after taking office. During arguments in the retrial after the court's decision in Kyles, one of Connick's subordinates told jurors that the court was wrong about the obligation to disclose exculpatory evidence, just as it had been wrong in Plessy v. Ferguson, the infamous 1896 segregation decision that sanctioned "separate but equal." Another former Connick assistant testified in 2007 that the office policy when it came to exculpatory evidence was to be "as restrictive as possible," and, "when in doubt, don't give it up."

The trial jury ruled for Thompson, and awarded him $14 million in damages. He also won at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, perhaps because the court was aware of its ruling in Cousin's lawsuit, and could no longer simply ignore what was going on in New Orleans. But Orleans Parish appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. And in 2011, the court rejected Thompson's suit in a 5-4 split.

Writing for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas's opinion illustrates how taking various theories of immunity in isolation can present a distorted, context-starved picture of what's really happening in America's courtrooms, and effectively shield prosecutors from any accountability.

Thomas noted, for example, that because Thompson hadn't attempted to argue a pattern of misconduct in Connick's office, the court couldn't consider it. That was true, but it was because the Fifth Circuit had rejected that argument two years earlier, in Cousin's case. Thomas also wrote that because prosecutors get specialized training in law school and are required to complete continuing education, a district attorney like Connick can be safe in assuming that his subordinates are already aware of their Brady obligations. Therefore his failure to train them on the matter wasn't such a big deal.

Thomas's opinion was at odds with Connick's professed ignorance of Brady and the DA's own admission that he hadn't bothered keeping up on the law. But even if Thomas was correct, consider the implication: It would mean that as far as the U.S. Supreme Court is concerned, when prosecutors fail in their obligations under Brady, they must do so knowingly and willingly. That means the city can't be held liable. But when prosecutors cheat willingly and knowingly, they're protected by absolute immunity. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a dissent for the minority. She was so incensed by the court's decision that she read her opinion from the bench.

The net result of the Supreme Court's immunity decisions is a sort of case-by-case buck-passing. In declining to attach liability under one theory, the court inevitably makes a good argument for why it should attach under a different one. Unfortunately, the court has already denied liability under that theory, too, and either has no interest in overturning that decision, or won't consider the possibility, because it wasn't argued.

Ultimately, the majority opinion in Thompson's case falls back on the argument that the legal profession is perfectly capable of regulating itself. "[A]n attorney who violates his or her ethical obligations is subject to professional discipline, including sanctions, suspension, and disbarment," Thomas wrote. In theory, perhaps. But not in reality, and once again, not in New Orleans.

A CULTURE OF CONVICTION

The particularly striking thing about that argument -- that self-regulation and professional discipline are sufficient to handle prosecutorial misconduct -- is that even in the specific Supreme Court cases where it has been made, and where the misconduct is acknowledged, the prosecutors were never disciplined or sanctioned. None of the prosecutors in Pottawottamie v. McGhee suffered professional repercussions for manufacturing evidence, for example. Neither did any of the men who prosecuted Thompson. In fact, there's a growing body of empirical data showing that the legal profession isn't really addressing prosecutorial misconduct at all.

In 2003, the Center for Public Integrity looked at more than 11,000 cases involving misconduct since 1970. Among those, the center found a little over 2,012 instances in which an appeals court found the misconduct material to the conviction and overturned it. Less than 50 cases resulted in any professional sanction for the prosecutor.

In 2010, USA Today published a six-month investigation of 201 cases involving misconduct by federal prosecutors. Of those, only one prosecutor "was barred even temporarily from practicing law for misconduct." The Justice Department wouldn't even tell the paper which case it was, citing concern for the prosecutor's privacy.

A 2006 review in the Yale Law Journal concluded that "[a] prosecutor's violation of the obligation to disclose favorable evidence accounts for more miscarriages of justice than any other type of malpractice, but is rarely sanctioned by courts, and almost never by disciplinary bodies."

An Innocence Project study of 75 DNA exonerations -- that is, cases where the defendant was later found to be unquestionably innocent -- found that prosecutorial misconduct factored into just under half of those wrongful convictions. According to a spokesman for the organization, none of the prosecutors in those cases faced any serious professional sanction.

A 2009 study (PDF) by the Northern California Innocence Project found 707 cases in which appeals courts had found prosecutor misconduct in the state between 1997 and 2009. But of the 4,741 attorneys the state bar disciplined over that period, just 10 were prosecutors. The study also found 67 prosecutors whom appeals courts had cited for multiple infractions. Only six were ever disciplined.

Most recently, in April, ProPublica published an investigation of 30 cases in New York City in which prosecutor misconduct had caused a conviction to be overturned. Only one prosecutor was significantly disciplined.

The 2011 Yale Law Journal survey of state disciplinary systems also found a host of problems with the way misconduct complaints against prosecutors are handled. In many states, for example, the entire disciplinary process occurs in secret, ostensibly to protect the reputation of the accused attorneys. (Nevermind that the people who were harmed by the misconduct weren't afforded the same courtesy.)

In some states, prosecutors are given the option of admitting wrongdoing and accepting a private reprimand, meaning neither their actions nor the disciplinary board's investigation will ever be made public. That hides the misconduct from the media, from defense attorneys and from the voters who elect these prosecutors. Secrecy also makes it more difficult to assess the pervasiveness of misconduct. Only one state, Illinois, publishes data on the number of complaints its disciplinary board has received and investigated.

The Yale review also found that some complaint processes are needlessly complicated. As of 2011, only four states offered the ability to file complaints online. Mississippi reminds potential complainants that "all lawyers are human," and warns of the damaging consequences of unfounded complaints. In 23 states, complainants have no option to appeal if their complaint is dismissed. The survey concluded that in too many states, "complaints must work their way through a byzantine structure" of procedures. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that most states have more checks to protect prosecutors from false misconduct complaints than they have to protect residents from false convictions.

Even when misconduct is exposed, it doesn't necessarily slow down a prosecutor's career. In Mississippi, for example, District Attorney Forrest Allgood has repeatedly used expert forensic witnesses whose credibility and credentials have been widely criticized by other forensic specialists. Two men Allgood has convicted of murder (one of whom was nearly executed) were later exonerated by DNA testing. Two others -- a mother accused of killing her newborn, and a 13-year-old boy -- were acquitted after they were granted new trials. Allgood continues to win reelection.

In Missouri, Kenny Hulshof was so good at winning convictions he was regularly called upon by the state attorney general's office to oversee death penalty cases. He has since been cited by two appellate judges -- one state, one federal -- for withholding evidence. In 2008, the Associated Press uncovered five other cases Hulshof prosecuted in which the defendant's guilt had since come into question. Nevertheless, Hulshof rode his tough-on-crime reputation to six terms in the U.S. Congress, a GOP gubernatorial nomination and then to a gig at the prestigious law firm Polsinelli.

In 2007, a California Court of Appeals found that a Tulare County deputy district attorney, Phil Cline, had improperly withheld an exculpatory audiotape of a witness interview in the murder trial of Mark Soderston. The tape was so damning to the prosecution's case, the court wrote, that "[t]his case raises the one issue that is the most feared aspect of our system -- that an innocent man might be convicted.” Unfortunately, Sodersten had had already died in prison. The court was so troubled by the case that it took the unusual step of evaluating his claim even though he was dead.

Not only was Cline never disciplined by the state bar, he was elected district attorney in 1992 and continued to win reelection, even after the court opinion chastising him. The other prosecutor in the case, Ronald Couillard, went on to become a judge.

One of the most egregious and widespread examples of prosecutorial agression and overreach in the history of the American criminal justice system was the mass panic over alleged ritual sex abuse in the 1980s and 1990s, and the wrongful convictions of dozens of innocent people that followed. Prosecutors across the country sent people to jail on horrific allegations of bizarre occult and satanic rituals that included sex with children, penetrating children with knives and orgies with children and animals. But the allegations inevitably stemmed solely from interviews investigators conducted with children, and in most cases there was no physical evidence of any abuse.

Few of the prosecutors in those cases suffered any harm to their careers. Most continued to get reelected, and some went on to higher office, including Ed Jagels in Kern County, California; Scott Harshbarger and Martha Coakley in Massachusetts; Daniel Ford, who is now a judge, also in Massachusetts; Robert Philibosian and Lael Rubin in California; and Janet Reno in Florida.

"Publicity and high conviction rates are a stepping stone to higher office," says Harvey Silverglate, a Boston-based criminal defense attorney and outspoken civil libertarian. He says prosecutors accused of going too far can frame the allegations as a testament to their willingness to lock up the bad guys. "Except in some rare cases, misconduct isn't going hurt a prosecutor's career. And it can often help," he says.

Back in Orleans Parish, the lead prosecutor in the John Thompson case, Eric Dubelier, was not only never disciplined, he was eventually appointed as an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, where he handled narcotics cases. In a prosecutor's world, that's a promotion. He was then promoted again to the Justice Department's Transnational and Major Crimes Section in Washington, D.C., where he worked for eight years. Since 1998, he has been a partner at the large international law firm Reed Smith, where he heads up its division on white-collar crime.

Silverglate says that's a common career track for federal prosecutors. "They often go on to take positions in white-collar law defense. And these are extremely lucrative positions -- 1 to 2 million dollar salaries. And they aren't being hired to litigate. The skills it takes to be a good prosecutor don't transfer to criminal defense. They're being hired to negotiate plea bargains with the friends they still have in the U.S. attorney offices. It's a huge racket."

"Tell me again about accountability," Thompson says from his office along St. Bernard Avenue, a rough, working-class neighborhood near the Treme. "You hear the politicians talk about criminals taking responsibility for their actions. That man [Dubelier] tried to have me killed. They had evidence of my innocence, they covered it up, and they tried to kill me anyway."

He gets up from his desk, paces, and his voice begins to rise again. "That's premeditated murder! I don't know how you call it anything else. And now he makes millions of dollars at one of the most powerful law firms in America." Thompson shakes his head. He paces back to his desk and sits down. "So tell me again about accountability."

This story appears in Issue 60 of our weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, in the iTunes App store, available Friday, August 2.

WHAT ISN'T UNETHICAL

Knowingly withholding exculpatory evidence is unquestionably a breach of ethics. But many of the recent stories to inspire public anger at the criminal justice system involve conduct that most state bar associations don't even consider unethical. While there were separate allegations of Brady violations in the Aaron Swartz case, for example, much of the backlash has been over what many saw as an unreasonably harsh battery of charges brought against the young activist. The prosecutors didn't have evidence for many of the charges, and they knew they didn't, the argument goes, so the charge stacking was really just an effort to bully Swartz into pleading guilty rather than go to trial and risk the possibility of a long prison sentence.

When asked about the appropriateness of the charges in the Swartz case, Attorney General Eric Holder told Congress he thought they were "a good use of prosecutorial discretion."

On the legal blog the Volokh Conspiracy, Orin Kerr, a George Washington University law professor and former clerk for Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, explained that at least under current practice, Holder may be right:

Yes, the prosecutors tried to force a plea deal by scaring the defendant with arguments that he would be locked away for a long time if he was convicted at trial. Yes, the prosecutors filed a superseding indictment designed to scare Swartz even more into pleading guilty (it actually had no effect on the likely sentence, but it’s a powerful scare tactic). Yes, the prosecutors insisted on jail time and a felony conviction as part of a plea. But it is not particularly surprising for federal prosecutors to use those tactics. What’s unusual about the Swartz case is that it involved a highly charismatic defendant with very powerful friends in a position to object to these common practices.

In fact, this kind of charge stacking is quite common, and considered a negotiating tactic in the plea bargain process. "It's ingrained in plea bargaining," Silverglate says. "It allows prosecutors to effectively punish defendants for insisting on their right to a jury trial."

The American Bar Association's Model Rules of Professional Conduct are the template by which state bar associations formulate their own ethical guidelines. As the Yale Law Journal article notes, "the Model Rule nowhere explains how prosecutors should conduct themselves in plea negotiations," and, "the ethics rules do not prohibit a prosecutor who wishes to gain leverage in plea negotiations from filing a charge that he has no intention of bringing to trial."

But it isn't just that charge stacking itself isn't considered unethical, it's that piling on charges is a tactic often used to encourage plea bargaining. And plea bargaining also tends to whitewash prosecutorial misconduct. Over 90 percent of criminal cases are resolved with plea bargains (PDF) before they ever get to trial. The defendants who accept these agreements are less likely to appeal, so the vast majority of criminal cases are never screened for prosecutorial misconduct.

To be fair, the primary reason most of the people charged with crimes plead out is that most of them are actually guilty. But it also isn't difficult to see how charge stacking could persuade an innocent person to accept, say, probation, instead of fighting in court and risking a prison sentence. After the drug arrest scandals in Tulia and Hearne, Texas, in the late 1990s, for example, dozens of people later found to be innocent pleaded guilty to minor drug felonies after they were threatened with more serious charges if they insisted on going to trial.

"There's no question the overall incidence of prosecutor misconduct is drastically masked by the high rate of plea bargains," Silverglate says. In some cases, even plea bargains can come about because of prosecutorial misconduct. "If as a defense attorney you discover misconduct and bring it to the attention of the prosecutor, they'll often come back with a very favorable offer for your client," Silverglate says. "They don't want to see it litigated." And at that point, most defense attorneys will place a higher priority on their obligation to their client, not their duty to report the misconduct.

It also isn't necessarily unethical for a prosecutor to introduce evidence he isn't certain is truthful. During a 2006 federal drug conspiracy trial against a Church Point, La., family, for instance, Assistant U.S. Attorney Brett Grayson put on a parade of jailhouse informants, each of whom claimed to have sold drugs to a woman named Ann Colomb and her sons. If you added up the amount of drugs the informants claimed to have sold to them, the Colombs -- who lived in a modest ranch home in a lower-middle-class neighborhood -- would have been among the biggest drug kingpins in the South.

It was later revealed that some inmates in a federal prison had somehow gotten a hold of a prosecutor file on the Colombs and were trading and selling the information. After memorizing the file, they'd then offer to testify in exchange for time off their own sentences. The case so outraged the federal district court judge, that he dropped all charges against the family and called for an investigation.

More than once during the Colomb trial, Grayson said it didn't matter if he believed the evidence he was putting on was truthful, it only mattered what the jury believed. According to several experts in legal ethics consulted for this article, Grayson was probably correct. While several said they personally felt a prosecutor should believe his own evidence, there's no professional requirement for such belief -- a prosecutor is only required to believe he has enough evidence to convict the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt.

"If a prosecutor has cut-and-dry, no-question-about-it proof that evidence he's about to put on isn't true, then yes, he has an ethical duty not to introduce that evidence," Silverglate says. "But it rarely works that way. If an eyewitness says something that's probably not true but benefits the state's case, a prosecutor can always find some subjective reason to explain why the witness could be believable and get the witness in front of a jury."

Requiring a prosecutor to have full faith in the evidence he puts on at trial would mean requiring him to do some investigating into the veracity of witnesses, the reliability of forensic evidence and so on. And that could potentially move him out from under the absolute immunity he enjoys as a prosecutor.

THE CHRISTMAS PARTY PROBLEM

It takes Sam Dalton a while to get to the door. On this June morning, the sky has opened up over his modest office in the Metairie area of New Orleans. He opens the door to reveal a welcome mat that reads, "Come Back With a Warrant." He apologizes for the delay, and with a motion of his walking stick, he invites me inside.

Dalton is fascinating character. He's alternately warm and accommodating, then irascible and prickly. He's sharp and incisive, but gets visibly frustrated when his age slows down his thoughts. And he's a civil rights icon who can be startlingly politically incorrect. Mostly, though, Dalton is a legal institution unto himself in southern Louisiana. He has defended over 300 capital cases, sparing 16 men from execution. He started a public defender system for indigent defendants that became a template for similar systems around the country. And it's probably safe to say he's the only person in history to have received a birthday card signed by 29 death row inmates. In September, Dalton will begin his 60th year practicing law in Louisiana, which means he's one of only a few attorneys left who also practiced before the Supreme Court's Brady decision in 1963.

"Brady made things a little better, at least at first," Dalton says. "The younger prosecutors tried to take it seriously, and would try to comply, but there was still a community standard to evade disclosure. So they'd actually hide it from their bosses when they'd turn over favorable evidence to us."

Dalton is at the heart of a current effort by some in the state's defense bar to impose some accountability on prosecutors in the wake of the Supreme Court decision in John Thompson's case. Now that the possibility of civil liability has been all but removed, there's a new urgency to either prod the state's Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC) to address misconduct, or to expose its ineffectiveness if it doesn't.

"The Brady problem really became atrocious under Connick," Dalton says of the former Orleans district attorney. "Nondisclosure was routine, and it's ridiculous to say he didn't know about it. He was too competent not to know what was happening. And it has gotten only marginally better since." (The district attorney's office in Orleans Parish did not return requests for comment.)

In Louisiana, ethics complaints against practicing attorneys are first considered by the ODC. If the office finds clear and convincing evidence of misconduct, it forwards its findings to an independent hearing committee made up of two lawyers and one non-lawyer, all of whom are volunteers. That committee must then sign off on the misconduct finding for the charge to go forward. Ultimately, the Louisiana Supreme Court makes the final decision on whether or not the charge has merit, and if so, on how to discipline the offending lawyer.

Current ODC chief counsel Charles Plattsmier admits there are major obstacles preventing his office from imposing any real accountability on wayward prosecutors. In his 17 years on the job, he can only recall three occasions in which a prosecutor has been disciplined for misconduct.

Plattsmier wouldn't talk about specific cases, but from public records, it's clear one of those disciplinary actions came against Roger Jordan, the prosecutor who convicted Shareef Cousin. For suppressing evidence in that case, the Louisiana Supreme Court in 2005 suspended Jordan from practicing law for three months, but then suspended that penalty. As long as Jordan isn't found to have committed misconduct again, he'll never have to serve the suspension. The court noted that it was the first time it had ever disciplined a prosecutor for misconduct.

Another occasion was the action taken against Mike Riehlmann, the attorney who heard the deathbed confession about the blood evidence in Thompson's case. Riehlmann played no part in the actual prosecution of Thompson, and he eventually worked with Thompson's attorneys to help set Thompson free. Yet he was the only attorney involved in the entire affair to face any discipline. Because Riehlmann did not disclose the confession for five years, Connick filed an ethics complaint against him. (Riehlmann was once a prosecutor, but not under Connick, and not at the time Connick filed the complaint.) Connick's complaint was upheld, and Riehlmann's law license was suspended for six months.

Dalton attended the hearing where the Louisiana Supreme Court suspended Riehlmann's law license. "Under the Louisiana Bar code of ethics, any attorney who is made aware of ethical misconduct by another attorney is obligated to file a complaint," Dalton says. But Riehlmann's sanction illustrates what may be the biggest barrier to self-regulation: Lawyers do not want to report other lawyers for ethical violations. "As I sat there and listened to these justices come down on this guy, really scolding him, I wanted his attorney to challenge them," Dalton recalls. "Those justices are all licensed lawyers in Louisiana. And some of them had found that prosecutors had withheld evidence in that same case, in violation of Brady. I wanted to ask them, why didn't you file a complaint?"

It's a good question. According to Plattsmier, Louisiana judges are bound by a code of judicial conduct that supersedes the bar's code of ethics. But that doesn't get them off the hook. The code "instructs judges to report and assist in misconduct investigations. But the word it uses is should, not shall," Plattsmier says. "So some judges take that instruction very seriously, but some just don't find it relevant." Plattsmier's office does not have jurisdiction over judges. Discipline of judges is handled by other judges.

"You have to remember that nearly all judges are former prosecutors," Dalton says. "There's an undercurrent of alliance between judges and prosecutors, so there's a certain collegiality there. They run in the same social circles. They attend the same Christmas parties."

Since his release, Thompson has given public talks, spoken on panels and participated in forums on how best to address prosecutor misconduct. He knows all about the Christmas party problem. "Even when I talk to judges and prosecutors who acknowledge there's a problem, who are sympathetic, even they will bring that up. They'll say, 'I've known Jack all my life. My kids go to school with his kids. He came to my Christmas party last year. How could I file a complaint against him? How could I discipline him, or take away his law license, when that's how he feeds and takes care of his family? I know Jenny and the kids. I can't do something that's going to put them out of their home.'"

"I get that," Thompson says. "If I'm honest with myself, if I'm forcing myself to see the world through someone else's eyes, I get that. But then what can we do about that? Who is going to file these complaints? Me? From a jail cell?"

He continues: "I just come back to the fact that they wanted me dead. I understand that maybe, in your heart of hearts, you really believed this guy was guilty. But at some point you started to find evidence that he wasn't. And instead of exposing that evidence, you hid it. Once you did that, you became a conspirator in my murder. If you're a prosecutor, your job is to prosecute murderers. To protect innocent people from being murdered. I was an innocent guy that the people in that office conspired to murder. And now you're saying you, Mr. Prosecutor, you can't protect me from these men who tried to kill me, because their wives and kids go to your Christmas party? You should be trying to put them in jail! But you can't even file an ethics complaint against him. No way. I understand what they're saying. But it just isn't an excuse."

It isn't just other prosecutors who shy away from reporting misconduct. According to Plattsmier, his office receives around 3,200 complaints per year. Family law gets more complaints than any other area of practice. "Criminal law gets its fair share," Plattsmier says, "But the criminal law complaints are almost exclusively against members of the defense bar. You can imagine why that might be. Everyone who gets convicted, whether it's of murder or a parking ticket, they tend to blame their lawyer."

According to Plattsmier, in his time at ODC, complaints against prosecutors have been almost nonexistent. That also seems to be true elsewhere. In 2010, Illinois considered over 4,000 complaints against attorneys licensed in the state. Of those, 99 alleged prosecutorial misconduct. Just one of those reached the stage of a formal hearing.

After a forum on wrongful convictions last year at Tulane University, Plattsmier asked the Innocence Project of New Orleans for a list of cases in which an innocent person had been convicted due to prosecutor misconduct. "I checked the list to see how many of the prosecutors had been reported to our office. Even I was surprised when we found that none of them had. No one had filed a complaint."

Though defense attorneys may seem most likely to file those complaints, few of them do -- and there are some good reasons why not. For one, ethics complaints usually aren't considered until criminal and civil trials are settled. That way, if a state supreme court makes a finding of ethical misconduct, it will have no impact on a client's criminal appeal or his lawsuit. More important, Plattsmier says, defense attorneys are reluctant to file complaints because of the damage a complaint could do to the working relationships they have with prosecutors. A complaint could make an aggrieved prosecutor and his colleagues less likely to cut deals or to ask judges for leniency for an attorney's other clients.

There's also the problem Harvey Silverglate described: When a defense attorney does find evidence of misconduct, it can be a bargaining chip, explicitly or implied, to negotiate a better plea bargain -- with the understanding that the misconduct not be made public. So while mass reporting of misconduct by criminal defense attorneys as a whole would likely be of enormous benefit to the criminal justice system and to defendants and general, there's little incentive for an individual attorney to report an individual prosecutor.

"That's why what Sam Dalton is doing is so important," says Ben Cohen, a defense attorney who practices in New Orleans, but lives in Ohio. "Filing an ethics complaint against a prosecutor can be devastating for a defense lawyer. It can ruin you professionally. You can't get a plea. You risk having them take it out on your clients. What Dalton has done is set an example. For a man of his stature, it means something."

Cohen recently filed his own ethics complaints alleging misconduct in the case of Jamaal Tucker, a client who in October 2010 was convicted of killing a man outside a public housing project in New Orleans. Assistant District Attorney Eusi Phillips's first two attempts to convict Tucker ended in mistrials, one after Judge Julian Parker found that prosecutors had violated his order to turn over exculpatory evidence. Parker even threatened to convene a grand jury to investigate the misconduct. One witness testified in Tucker's second trial that he was recanting his prior statements, and could no longer recall witnessing the shooting. Prosecutors then threatened him with perjury charges. The same witness then testified again at Tucker's third trial, perjury charges still hanging, and was once again able to recall what he thought he had seen.

Two other witnesses had cut deals with prosecutors, yet were still permitted to tell the jury otherwise. One of them, Morris Greene, told the jury that he was testifying against Tucker "out of the goodness of my heart." But Greene had sent a letter to the office of current Orleans Parish District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro asking for money and leniency on his own charges for armed robbery in Lafayette Parish. That letter wasn't turned over to Tucker's defense. Cohen knew of the charges against Greene, and sent an investigator to sit on the proceedings in Lafayette, about 135 miles west of New Orleans. According to Cohen, a prosecutor in Lafayette Parish told the court that he had just received a phone call from Cannizzaro, and that he would be allowing Greene to withdraw his guilty plea in the armed robbery case. Greene was released.

The judge in Tucker's case then subpoenaed Cannizzaro to explain the mysterious phone call. Instead, on the day Cannizzaro was scheduled to testify, his office conceded and Tucker was granted a new trial.

The ODC found no ethical violations on the part of Cannizzaro or Phillips. "The justification was that there was no proof of a deal, so there was no ethical violation," Cohen says. "But any first-year law student could tell you why that's wrong. Even if there wasn't a deal, Greene's letter shows that he asked for and was expecting one, and that's what was driving his testimony. ... The letter was never disclosed, and he was allowed to testify that he was expecting nothing."

(Shortly before publication, Cohen was informed that his appeal of the ruling was successful, and that his complaint against Phillips would be reinstated.)

Plattsmier says he sympathizes. "I understand the frustration. I do. You hear about these overturned convictions, and then you hear that only three prosecutors have been disciplined in 20 years, and the natural reaction is, 'So what's wrong with the system?'"

Beyond a reluctance to report misconduct, Plattsmier points to other possible explanations for the discrepancy between appeals court findings of misconduct and so few disciplinary actions against prosecutors. First, he says, because disciplinary boards usually only start investigating a case after it has been resolved both criminally and civilly, time can be a factor. "Criminal cases have long, long lives," he says. "It can be years or decades before misconduct is discovered. You're then going back to piece together events from long ago. That can be a challenge. The prosecutor you're investigating may not even be a prosecutor anymore, so there may no longer be a file. That's not an excuse. It's just a reality."

Plattsmier also emphasizes that a finding of "misconduct" by an appeals court isn't necessarily a breach of ethics. To constitute an ethical violation, the misconduct must be willful. For example, if defense attorneys discover after conviction that a police officer withheld information favorable to the defendant, an appeals court would likely classify that failure to disclose as prosecutorial misconduct. But it wouldn't be an ethical violation on the part of the prosecutor. "You must know of the evidence in order for it to be an ethical violation not to turn it over," Plattsmier says.

One way a prosecutor could protect himself from accusations of failing to turn over exculpatory evidence gathered by police, then, is to make a habit of not asking the police for such evidence. That can create an unhealthy culture in which prosecutors take a don't-ask-questions approach to police misconduct.

In September 2011, for example, Cannizzaro dropped drug charges against Eddie Triplett, who had already served 12 years in prison for cocaine possession. In 1999, two New Orleans police officers had detained another man on the street under suspicion of drug possession. For reasons that aren't entirely clear, they also detained Triplett. Police attributed the cocaine they found on the first man to Triplett, then testified against him at trial. Triplett was released after his attorneys found the long-suppressed police report which described what had actually happened. The two officers involved are still on the force in New Orleans. And though Cannizzaro was somewhat critical of the police department after freeing Triplett, one of his assistants publicly defended the officers.

While it's probably unfair to point the finger at prosecutors when police withhold evidence, it's also important to at least acknowledge that not holding prosecutors accountable can encourage a willful blindness to police misconduct. In the Triplett case, a prosecutor more skeptical of the police, or at least more vigilant about reviewing police reports and case files, could have prevented an unjust conviction.

That sort of push and pull of incentives for prosecutors can complicate efforts to improve the system. But there appear to be more functional problems at work in Orleans Parish, even since the Supreme Court's Thompson decision.

Sam Dalton began his personal campaign for prosecutor accountability nearly two years ago by going after six prosecutors for alleged misconduct during the murder trial of Michael Anderson. Nothing has happened since.

Anderson was convicted in 2009 of gunning down five men in an S.U.V. in the New Orleans neighborhood of Central City three years earlier. He was sentenced to death. It was the first capital case won by Cannizzaro, who at the time was new to his job as district attorney.

Anderson was awarded a new trial in 2010 when a judge found that prosecutors had failed to turn over exculpatory evidence. That evidence included a recorded interview in which the state's main eyewitness made statements that undermined both her story and her credibility, and a deal the state had cut with a jailhouse informant who claimed Anderson had confessed to him. The informant, Ronnie Morgan, was facing his own charges for several armed robberies. Prosecutors let him testify in Anderson's trial that he was getting no favors for his testimony, even though he was later allowed to plead to charges in what another judge would call "the deal of the century."

Dalton filed eight complaints with the ODC in October 2011. By the following March, he had yet to even hear confirmation that the ODC had received his complaints. He sent another letter. He still received no response. In August of last year, he sent a colleague to the ODC office to at least make sure the complaints had been delivered. She was told that they hadn't. Dalton's colleague then produced the name of the ODC staffer who had signed for the FedEx package containing the complaints. At that point, the office conceded that it had in fact received the complaints, but was still researching them, and would notify Dalton by the end of the month. When he had received no response by the middle of September -- nearly a year after his initial filing -- Dalton sent yet another letter. As of this writing, he still has yet to hear back from the ODC.

Last August, Kathy Kelly of the Louisiana Capital Post-Conviction Office also filed a complaint with the ODC, against Roger Jordan, the prosecutor in the Juan Smith case. As of this writing, she too has yet to hear back from the office.

Plattsmier says that while he can't talk about specific cases, he would be "very surprised" if his office had taken months to confirm receipt of a complaint. "That would indicate to me that something is very wrong, that there is some sort of miscommunication. I would encourage anyone who has filed a complaint and not heard anything back at all to contact me directly," he says.

Dalton emphasized that Plattsmier is an excellent attorney and an honorable man whom he holds in high regard. "I wouldn't ever question his integrity," Dalton says. Emily Maw at the New Orleans Innocence Project echoed that sentiment. "I think he's an ally. He recognizes there's a problem. And he has reached out to us for ideas on how to fix it."

But Dalton still wonders what's going on with his complaints. "I just can't explain it. It has to be something intentional coming from someone, somewhere," he says. "It could be anything from just a friendly alliance with people in power to something more sinister. But it isn't accidental."

RESURRECTION AND REFORM

Back on St. Bernard Avenue, John Thompson is working with a plumber. Shareef Cousin is eating lunch. Five years ago, the two men co-founded Resurrection After Exoneration, a non-profit organization that helps exonerees re-enter society.

"John and I planned this whole thing on death row," Cousin says. "We had cells right next to each other."

Thompson comes out from a back room. "Cell two and cell three!" he calls out. "We always knew we was going to get out."

"We motivated each other," Cousin says, "inspired each other to keep up the fight. So we always knew we wanted to work together to create something positive from all of this when we got out."

Bearded and bespectacled, Cousin comes off as restrained and pensive. Where Thompson is loud and brash, Cousin is quiet and standoffish. Thompson started our interview by scarfing down a box of fast food. Cousin has a plate of what looks like health food, but insists on putting it aside as we talk.

Cousin had his own experience with the difficulties of re-entry. In 2008, shortly after he got out of prison, he pleaded guilty to using his boss's identity to apply for and use some credit cards. "When I got out of prison, I had spent half my life behind bars," Cousin says. "I was impressionable. I had some mental health issues that had gone untreated. And I had little money. Those aren't excuses. But the experience made me more aware of the problems exonerees face when they get out. Especially the mental health aspects, which I think get overlooked. People understand that people first getting out may need money or housing. But doing time does things to people, even innocent people. If you don't get your mind right, get some counseling, you could find yourself back in prison."

At Resurrection, Cousin now counsels recent exonerees and directs them to mental health services. He also trains and employs some of them at a screen-printing company he and Thompson started through the non-profit. "Right now we have contracts to print school uniforms for several schools in Orleans Parish," he says. "And we have the city's ear right now, so we're in the process of lining up more."

Cousin talks briefly about his case, and about prosecutorial misconduct, but he isn't interested in delving into specifics. "I let John handle reforming the system," Cousin says. "It just gets me too upset. I don't like to be angry. So I handle the re-entry stuff. I let him deal with the activism."

Currently, Thompson is planning an exoneree march on Washington. "We're hoping to get at least one exoneree from all 50 states," he says. "And we're going to take a petition to Eric Holder demanding that he go after these prosecutors. That's his job. He's the attorney general. He should be protecting us from the people in the legal system who would do us harm, and he hasn't done anything about it."

Nationally, the public is becoming more aware of prosecutor misconduct, thanks in part to the Ken Anderson and Mike Nifong prosecutions, the seemingly endless stream of DNA exonerations and publicity over cases like Thompson's.

After a first term in which he became the national face of reforming the culture in prosecutors' offices, Dallas County District Attorney Craig Watkins won reelection by a slim margin in 2010. And on a few occasions, voters have chosen to punish wayward prosecutors. The same year in Colorado, for example, voters declined to retain state judges Terence Gilmore and Jolene Blair, two former prosecutors who in 1999 won a murder conviction against Tim Masters. Masters was later exonerated, and in 2008 Gilmore and Blair were reprimanded by the Colorado Supreme Court for their misconduct in the case.

But in much of the country, prosecutors still mostly earn voter favor by racking up convictions. And the political and criminal justice systems present some formidable obstacles to reform.

In 2004, for example, the California legislature created the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice, a panel of current and former judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys and police officials. They were charged with coming up with policies that could help prevent wrongful convictions. In 2006 the group delivered a series of sensible recommendations, including simple changes to the way eyewitnesses are presented with lineups, requiring corroboration before using testimony from jailhouse informants and requiring video recording of police interrogations. The measures passed both houses of the state legislature, but were then vetoed by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger after heavy lobbying by the California District Attorney's Association.

Common misconceptions among prosecutors about their Brady obligations remain, and disabusing them of those notions may be an important first step toward reform. "I think education of prosecutors can help," Plattsmier says. "We've been working with DAs to make sure their offices are thoroughly educated on their Brady obligations."

Plattsmier says one misperception concerns the materiality test the Supreme Court has laid out for Brady violations. This is the doctrine that says that even if a prosecutor withheld information favorable to the defense, the conviction can stand if the withheld information likely wouldn't have altered the verdict.

"Some prosecutors have assumed that gives them the authority to decide what information is and isn't material to guilt. But that isn't how it works. It isn't up to their discretion. From an ethics standpoint, if it's favorable to the defense, they're obligated to turn it over. And we've told them that the fact that the information they withheld was deemed immaterial by a court doesn't preclude us from opening an investigation."

Another possible reform would simply be to require prosecutors to share everything with defense attorneys -- what's known as an "open file" policy.

"I think open file is the minimum reform we need right now," says Michael Banks, the attorney for Thompson. "There will always be rogue prosecutors to deal with, and we need some changes to handle them better. But open file would really improve the way evidence is handled."

Others are more skeptical. "Open file only works if you have a prosecutor who keeps a good file," says the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers' Steven Benjamin. "Prosecutors who hide information or who don't investigate police reports and procedures aren't going to have that information in their files. I think it would help with unintentional mistakes, but it won't help much with willful misconduct, or with willful blindness."

"Open file could help," Plattsmier says. "But you have to be wary about the safety of witnesses. There are some real concerns there."

Of course, neither better prosecutor education nor open file access would address the fact that even the most willful, egregious misconduct is rarely punished.

"I wouldn't be at this job if I didn't think we were making a difference," Plattsmier says. "You don't take this job to be liked. I save a lot of money on stamps every Christmas. Things are getting better, but I understand the view that it isn't enough. Ultimately, I think the courts are going to have to take a more active role in this. Judges are going to have to start reporting misconduct to the bar. They're really in the best position to do so."

Thompson says the reform message could be more effective if it focused on the other injustice of a wrongful conviction: The real perpetrator goes free. The killer in Shareef Cousin's case has never been caught.

"Stop showing pictures of the innocent and wrongly convicted," Thompson says. "Start showing the faces of the people the real murderer kills later. And then let's point out that when prosecutors conspire to convict the wrong man, they're aiding and abetting those later crimes. Are we ready to address that?"

Banks recalls a recent Innocence Project event where he met an exoneree whose daughter was just two weeks old when he went to prison. "He got out 23 years later. My own daughter is 23. I remember thinking how incredible it must have been to be released from prison and to have seen this woman, his daughter, now fully grown, whose entire life was really a timeline of his time behind bars."