As he lay dying, his brain exposed by a piece of shrapnel the size of a bottle cap, Cpl. Bruce Moncur's thoughts drifted to Pleasure Beach.

As he lay dying, his brain exposed by a piece of shrapnel the size of a bottle cap, Cpl. Bruce Moncur's thoughts drifted to Pleasure Beach.It was Labour Day weekend at home in Canada, which seemed like a different planet than the Panjwai district of Afghanistan.

He guessed his family had finished the chili cook-off at their spot by the water in Essex, Ontario. Maybe they were playing horseshoes.

Everyone would be together, blissfully unaware of the friendly fire. The bloody mess in the sand, the yellow liquid coming out of his ears and nose.

His peace made with God, Moncur tried to reach them — somehow — by repeating the same simple message.

I just want you to know that I love you.

Then, he gave up. He resigned himself to the fact he wouldn't be going home.

He was 22 years old.

He had been in Afghanistan for three weeks.

***

How much is a leg worth?

Rather, how much is the pain of losing a leg worth?

What about an arm? A left thumb? A spleen? A right foot?

These are the kinds of questions Moncur didn't have time to ask after the incident that changed him. The focus, then, was survival.

He was caught in a friendly fire mishap on Sept. 4, 2006, in which an American aircraft mistakenly opened fire on a Canadian platoon during Operation Medusa — a Canadian-led offensive. An A-10 attack jet inadvertently strafed soldiers huddled around a garbage-lit fire at the base of the rugged hillside of Masum Ghar, west of Kandahar City. Pte. Mark Anthony Graham was killed.

Moncur was eating breakfast at the time.

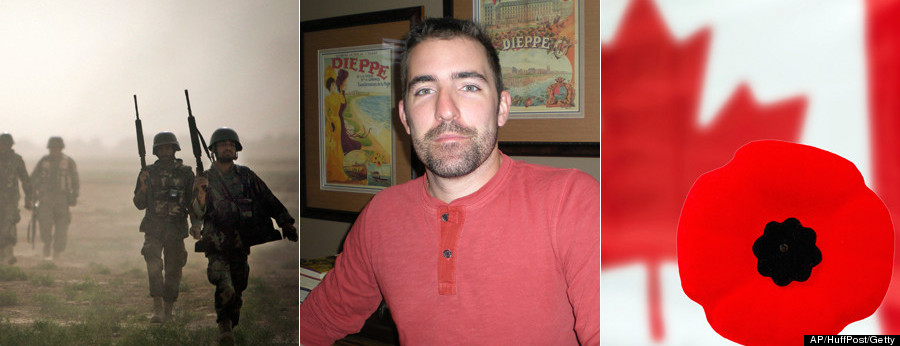

"The next thing I know I was tossed in the air. Just flung," he said recently from his home in Windsor, Ont., seven years later. "And I landed with such impact it knocked me unconscious."

When he came to, his right arm was flailing "like a fish out of water." He was certain it was detached but soon learned he still had two working arms, two good legs.

Then, the blood began to pour, ceaselessly, down his face.

Moncur tried to catch it, cupping his hands and letting them fill, before conceding the futility of such a move.

Bruce, you can't use that anymore, he thought.

Moncur crawled on his belly — his face scraping against rock because he couldn't lift his head — until he reached fellow soldiers who had little idea how to help him. He was also hit with shrapnel in the back and buttocks.

His friends loaded him on a stretcher and kissed his cheek, convinced they'd never see him alive again.

Moncur was airlifted to Camp Nathan Smith in Kandahar, where he underwent a surgery in which his odds of survival were pegged at 50/50. He had a second surgery in Landstuhl, Germany, but a piece of uranium was lodged too far inside his head to be removed.

A week later, he was sent to Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto to begin his long road to peace.

In total, five per cent of his brain was removed.

How much is that pain worth?

***

In 2005, Canada changed the way it compensates disabled and injured veterans with the unanimous adoption of the Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act, better known as the New Veterans Charter.

Though enacted by the Liberal government of former prime minister Paul Martin, the charter came into force on April 1, 2006, under Stephen Harper's Conservatives.

Up until that point, the Pension Act ensured Canada's injured veterans received monthly allowances and pensions, dependent on the severity of disabilities and marital and family status. According to a 2011 Queen's University study, a maximum disability pension of up to $2,397.83 a month was available tax-free for the rest of a veteran's life, with hundreds extra to provide for a spouse and children.

The charter, however, brought in one-time, lump sum payments dependent on disability, military rank and eligibility for work. The maximum amount of these awards — meant to compensate for pain and suffering, not replace income — was set at $250,000 in 2006. After being indexed for inflation, it now sits at $298,588.

With a focus on helping veterans transition to civilian life, the charter contains rehabilitation and vocational services not available under the old system. It also offers a monthly, taxable earnings loss benefit that ensures, for at least two years, veterans taking part in rehabilitation programs receive up to 75 per cent of their pre-release salary. Vets who are deemed to be permanently incapacitated can have this benefit extended until the age of 65.

In 2011, Conservatives increased the allowance for the permanently incapacitated and gave eligible vets the option to receive disability awards as annual installments, instead of all at once.

Veterans Affairs Minister Julian Fantino says the Conservative government has invested almost $5 billion new dollars in retraining, rehabilitation and medical and financial benefits.

But the workers-compensation-style model of paying for pain and suffering, for those body parts irreparably damaged or gone forever, hasn't changed. An arm or a leg should get a soldier the maximum payout, but other body parts are assessed differently according to what soldiers refer to as a "meat chart."

And the message from the veterans ombudsman, veterans groups, former soldiers and the Royal Canadian Legion on that particular issue is clear: injured Canadian soldiers deserve better.

***

$22,000 and change.

That's what Cpl. Bruce Moncur says he received back in 2006 for that chunk of his brain and other injuries.

Moncur would later get a lump sum compensation for the post-traumatic stress disorder he was diagnosed with in 2010. He says that most vets he has spoken to say they have received a one-time payment of $120,000 to $150,000 for a PTSD diagnosis.

The military covered a year of his university education at the University of Windsor as part of the regular officer training program. After he "went civilian" in 2010, he paid for the rest of his history degree on his own.

At the time of his injury, he was assessed against the maximum of $250,000, meaning Veterans Affairs pegged his disability level at less than 10 per cent. If he had been confined to a wheelchair, he would have had a disability level of 100 per cent.

"I couldn't believe it. I was expecting at least six figures," he said. "I mean, I lost brain."

Moncur said the cheque arrived without explanation while he was recovering at his aunt's home in Harrow, Ont.

They assumed it was a mistake. It had to be.

After all, he was working through intensive physiotherapy and occupational therapy, learning how to speak properly again, to read, to walk without help. The headaches were excruciating, the fatigue was seemingly endless.

Moncur decided to appeal, but had no idea what to do. He felt Veterans Affairs representatives weren't interested in explaining the process, but they did tell him his lawyer for the appeal process would not be covered. His local MP Jeff Watson conceded he had "no idea" how the process worked, Moncur said.

For the first couple years, he felt he was banging his head against a wall, uranium in there and all.

But after claiming PTSD, he was given a helpful case worker in Veterans Affair Windsor, a district office that will close due to cuts in February, 2014. She pointed him in the direction of a Legion representative who used to work for the government department.

The rep explained to Moncur that while he could get unlimited physical reassessments, he would only get one formal appeal on his award.

"The guy from the Legion had to tell me that you didn't want to use your only appeal," Moncur said.

The wounded soldier feared he was getting the runaround from the government all along.

Royal Canadian Legion representative Andrea Siew says the government doesn't do enough to help vets understand how the new system works.

And with cuts to Veterans Affairs, it will be even more difficult to have knowledgeable people in district offices.

The message is often "go online and figure it out," she said, or go into a Service Canada and submit applications at a kiosk. Veterans need someone to talk to, she said, particularly the injured ones.

"If I'm in my mother's basement, I'm 23 years old, I'm a reservist who served in Afghanistan… now living in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, where they're closing a district office, how do I find out about all this stuff?" she asked.

"There's lots of things that are there, but it's really complicated."

Legion reps from 25 service offices across Canada are going to every single reserve unit to let them know they can apply for disability benefits.

"But Veterans Affairs isn't doing that," she said.

Siews says the Legion wants disability awards raised to what is provided to injured civilian workers.

"The problem with the disability award is it's not consistent with federal court decisions for injury cases. It's lower," she said. "Probably $50,000 lower than what civilian courts are providing for workplace injuries."

Moncur's physical reassessment — which he said amounted to a basic check-up — came back with no change in February, 2013.

But his biggest frustration was still to come.

***

Nearly 100 years ago, before the Battle of Vimy Ridge, Prime Minister Robert Borden made a vow to troops that laid the groundwork for decades of government policy, but has never been enshrined in the Constitution.

"You can go into this action feeling assured of this, and as the head of the government I give you this assurance: That you need not fear that the government and the country will fail to show just appreciation of your service to the country and Empire in what you are about to do and what you have already done," Borden said.

"The government and the country will consider it their first duty to see that a proper appreciation of your effort and of your courage is brought to the notice of people at home… that no man, whether he goes back or whether he remains in Flanders, will have just cause to reproach the government for having broken faith with the men who won and the men who died."

Today, the Harper government is facing a class-action lawsuit from soldiers who served in Afghanistan and feel that solemn promise has been broken.

These veterans say the 2006 charter discriminates against them by providing less than what veterans of the Second World War and Korea received.

One of the plaintiffs, Maj. Mark Campbell, lost both legs above the knee, a testicle, and had an eardrum ruptured after a roadside explosion in 2008.

He received a lump sum payment of $260,000 for pain and suffering, on top of his military pension, earnings loss benefit and permanent impairment allowance.

The government's defence is that it isn't bound by the promises of previous governments, dating back to the First World War, in the care of wounded soldiers.

Gordon Moore, the Dominion president of the Legion, has called that argument "reprehensible."

"There is only one veteran, whether you are 19 years of age or 105," he said in a recent interview.

The suit is largely a result of the advocacy of Jim Scott, whose son, Dan, was injured in Afghanistan after he was hit with discharge from a Canadian mine in 2010.

Dan, then a part-time reservist, lost a kidney, spleen, and part of his pancreas. He was awarded $41,500.

"My wife actually works on litigated bodily injury claims for an insurance company, so she knew that was disproportionately low," said Jim, a retired police sergeant in Surrey, B.C.

He said he checked with a workers compensation program in British Columbia and found a similar injury in a logging accident would pay around $1,400 a month.

Dan told his father there were plenty of other soldiers receiving low settlements.

After the Scott family was told by Veterans Affairs that this was how things work under the new funding formula, Jim set out to find a law firm that would have the charter impartially reviewed in court. They all told him the Crown Liability and Proceeding Act prevents soldiers from suing on matters of remuneration.

Jim believes the government "picked on soldiers" because they were unable to sue for more and the feds wanted to liquidate their liability, not unlike someone wanting to quickly settle things after a car accident.

National firm Miller Thomson agreed to take the case pro bono, Jim said, because it's something that needs fixing. Jim founded an organization, The Equitas Society, which is handling the disbursement costs — expert medical opinions, court filing fees — which he pegs at a minimum of $100,000.

There's no money to be made in this lawsuit, but Jim hopes a judge will order the government to change the way it compensates injured veterans.

"These kids who are missing parts of their legs or have their legs reconstructed with steel rods and plates, you can tell when they walk down the street that they're disabled," he said. "The compensation that they got is basically nothing in comparison to what other Canadians would get and I just don't know why you would want to select soldiers as the people we want to compensate the least."

Jim, a former Conservative Party riding president, said while this isn't about blaming the Harper government, Tories own the issue now.

"Personally, I just think that the government's priority is to balance the budget by 2015 and this would blow a big hole in that plan," he said.

***

Michael Blais has a simple message for veterans who receive disability awards: appeal.

"They always low-ball you," he said.

The president and founder of The Canadian Veterans Advocacy says vets from the war in Afghanistan are being treated in an "unconscionable" manner on the issue of pain and suffering.

Blais, himself a former soldier on a monthly disability pension, said Moncur's case is another "obscene" example.

"Injuries like that to the brain, they don't just heal up," he said. "You don't just stick a Band-Aid on it."

While conceding the new charter has good elements, Blais says that by weighing the sacrifices of one soldier differently than another, a "sacred obligation" of equal respect and care is not being met.

Blais presents the comparison of "Sergeant Juno Beach" and "Sergeant Panjwai Valley." Both are about 25, married, with two kids.

Sergeant Juno Beach loses two legs in 1944, and is provided, under the Pension Act, a monthly pension based on his disability for the rest of his life.

"Let's say he lives 60 years. When you add up all these pensions, pain and suffering awards, the sum comes up to almost $2 million, if not more," Blais said.

Today, Sergeant Panjwai Valley loses both legs in the Afghan war and receives, under the new rules, a maximum of $298,588 for that suffering.

Blais calls that maximum number "disgusting."

"As we assess the consequences of war, as we see those returning to our community bereft of arms and legs, scarred emotionally, mentally and physically, we have to recognize that sacrifice is equal to those who served in generations before," he said.

At a minimum, he says disability awards should be raised and tells vets who receive them to ask if they truly reflect their level of sacrifice.

"We must stand together and fight to ensure that the standards our forefathers set in blood, courage and incredible sacrifice are extended to those today who bear the same cross, who have offered the same level of sacrifice, who have suffered the same consequences of war," he said.

***

Cpl. Bruce Moncur, now 30, keeps his military medals in his underwear drawer. When he sees them, he knows it’s time for laundry.

Reminders are helpful for someone with short-term memory loss.

"I can't tell you how many appointments I've missed, how many parties I've forgotten," he said. "Sometimes I feel like an old man."

Moncur has a large, visible scar of a few inches on his head. He says he sees a psychiatrist twice a month and gets a neurological exam each year. He often gets dizzy spells and requires 12 hours of sleep. His dreams are horrible and the fatigue makes the PTSD worse. He has anger issues, at times, and doesn't do well with crowds.

His head aches, often.

And he is absolutely petrified of Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease robbing him of a happy life with a wife and kids, someday. He fears his brain injury has increased his risk of those diseases.

He says completing his history degree this past January was one of the hardest things he's ever done. It took him weeks to recover after exams.

"I would push myself to a level that it would literally drain the life out of me," Moncur said.

But despite all this, Moncur said he learned this past summer from a Veterans Affairs employee that his injury had been placed in the category of "headaches."

He said it took him seven years to learn that chunk of information and resents the classification deeply.

"It's not just headaches," he said. "It's being shot in the head."

The former soldier will continue with the next steps of his appeal: answering in detail questions about his quality of life and getting a doctor to complete a 15-page questionnaire. But he says he'll do so at his own pace.

Or, if it's easier, Moncur has another offer for the government.

"I'll give you the $22,000 back. I still have the $22,000, I didn't spend it. I didn't squander it," he said.

"You can give me my brains in a jar and I'll put it on my mantle."

***

Canada's veterans ombudsman has said, as a "first step," the maximum amount for disability awards should be raised to $342,000 — the current judicial cap for non-pecuniary damages awarded by Canadian courts.

Ombudsman Guy Parent's long-awaited assessment of the charter, released last month, meticulously weighed benefits and entitlements under the new charter with those from the old pension-for-life system.

In the most noteworthy revelation, Parent highlighted that hundreds of severely disabled veterans will take a major financial hit once they retire because some benefits will end at 65.

But the review paper only briefly touched on the issue of disability awards, which have not been increased, beyond annual indexing, since 2006.

In his report, Parent urged Veterans Affairs to revisit how they compensate veterans who have suffered in the line of duty. He said the government needs to conduct research and talk to veterans about what the maximum compensation should be.

As of March 2013, there were 38,380 veterans in receipt of the disability award, with that number expected to increase by 5,000 per year over the next five years.

Parent's analysis shows that increasing disability awards would cost taxpayers about $70 million.

A review of Bill C-55, which enacted the enhancements made by Tories in 2011, is required by legislation and expected this fall.

***

Moncur doesn't want to sound bitter.

At a Windsor bar called Rock Bottom, where they still let you throw peanut shells on the ground, he says almost dying puts everything in perspective. So too does his job working with the developmentally challenged at Community Living Essex County.

On Remembrance Day, he says he’ll have a drink and remember his buddies who died, the families they left behind.

"And how close my family was to losing me," he said.

But he won't dwell. That's just too tiresome.

Would the kid who went to war looking for adventure do it all over again? No chance. And, when asked, he tells young people to avoid joining the military unless there is no other option.

"Don't get caught up in the romance of fighting for your country," he said. "Don't get caught up in all the stories they tell you."

Still, he knows he can't change the past, what happened to him.

And while he feels betrayed, at times, by the government whose call he answered, he says he doesn't want to be angry anymore.

"I just want this to end," he said. "But I'm not willing to be treated in such a way that is demeaning or under-represents my sacrifice."

Despite it all, Moncur says he hasn't been this happy in years. Sure, he's missing a part of himself and the money he thinks he has more than earned. But he's alive.

He's found a girl he can't stop talking about.

And he gets to see sunset glow.

A spokeswoman for Veterans Affairs said staff were unavailable for an interview about this story with The Huffington Post Canada.

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.ca

Author: Ryan Maloney

No comments:

Post a Comment