-

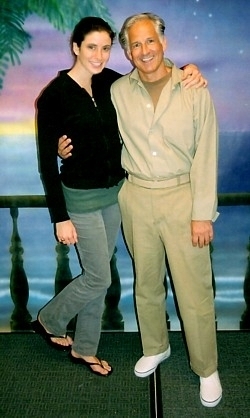

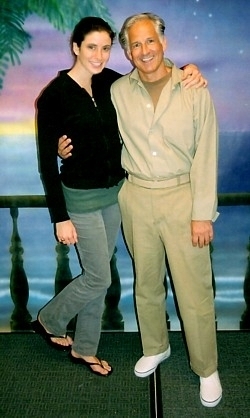

Alice Marie Johnson

via ACLU

via ACLU

Alice Marie Johnson, a single mother struggling

to raise her five children, was sentenced to life without parole for

acting as a middle man in several drug deals. She says she turned to the

trade out of desperation in order to make ends meet for her family.

While in prison, Johnson has become an ordained minister and has served

as a mentor and tutor for other inmates. “It feels like I am sitting on

death row. Unless things change, I will never go home alive," she told

the ACLU.

-

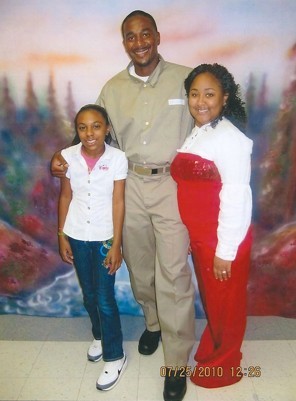

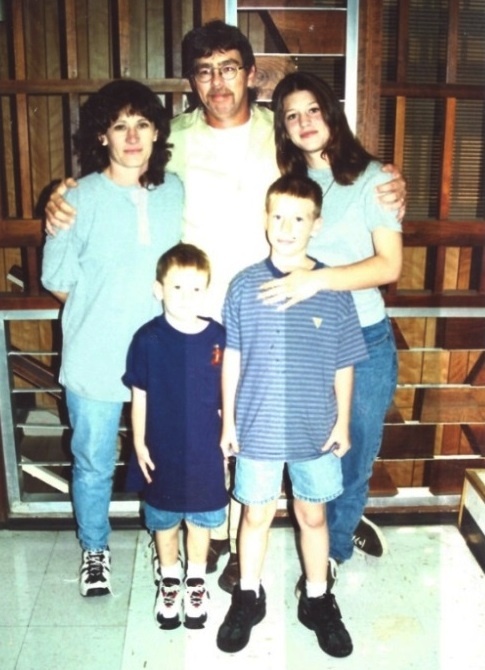

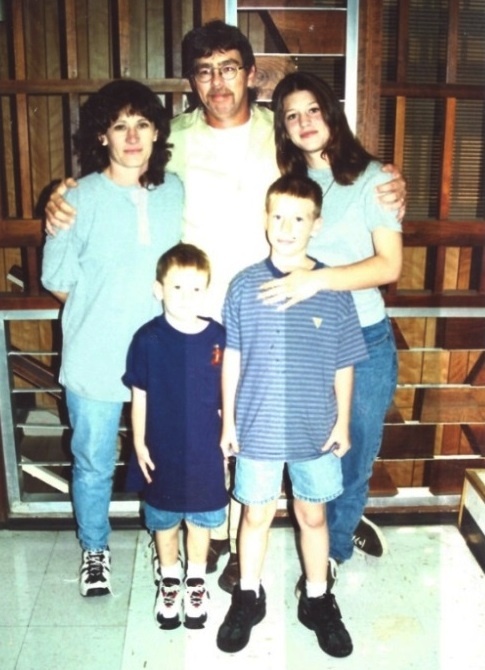

Danielle Metz

via ACLU

via ACLU

Danielle Metz is serving three life sentences for

her involvement in her husband's cocaine distribution enterprise -- her

first offense. Her jury was made up of 11 white jurors and one black

juror, and she was convicted largely on the testimony of her aunt.

Raised in New Orleans, Metz was the youngest of nine children raised in

New Orleans, and first became pregnant when she was 17. She is now a

mother of two.

"To be away from my kids, to miss them growing up, to have to parent

them over the phone and in the visitation room, to miss my daughter’s

wedding, took a piece of me that can’t be replaced," Metz told the ACLU.

"It’s a tragedy shared by women, children, families and communities

across this country … leaving the kids to think they don’t have a hope

in the world."

-

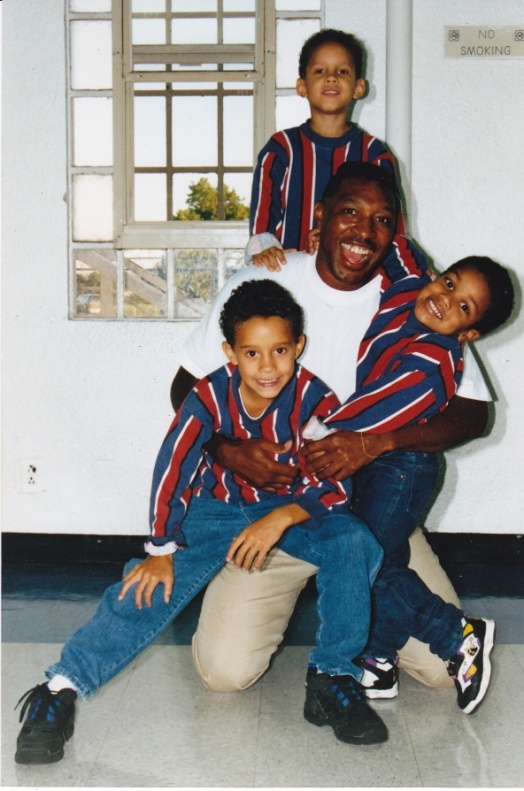

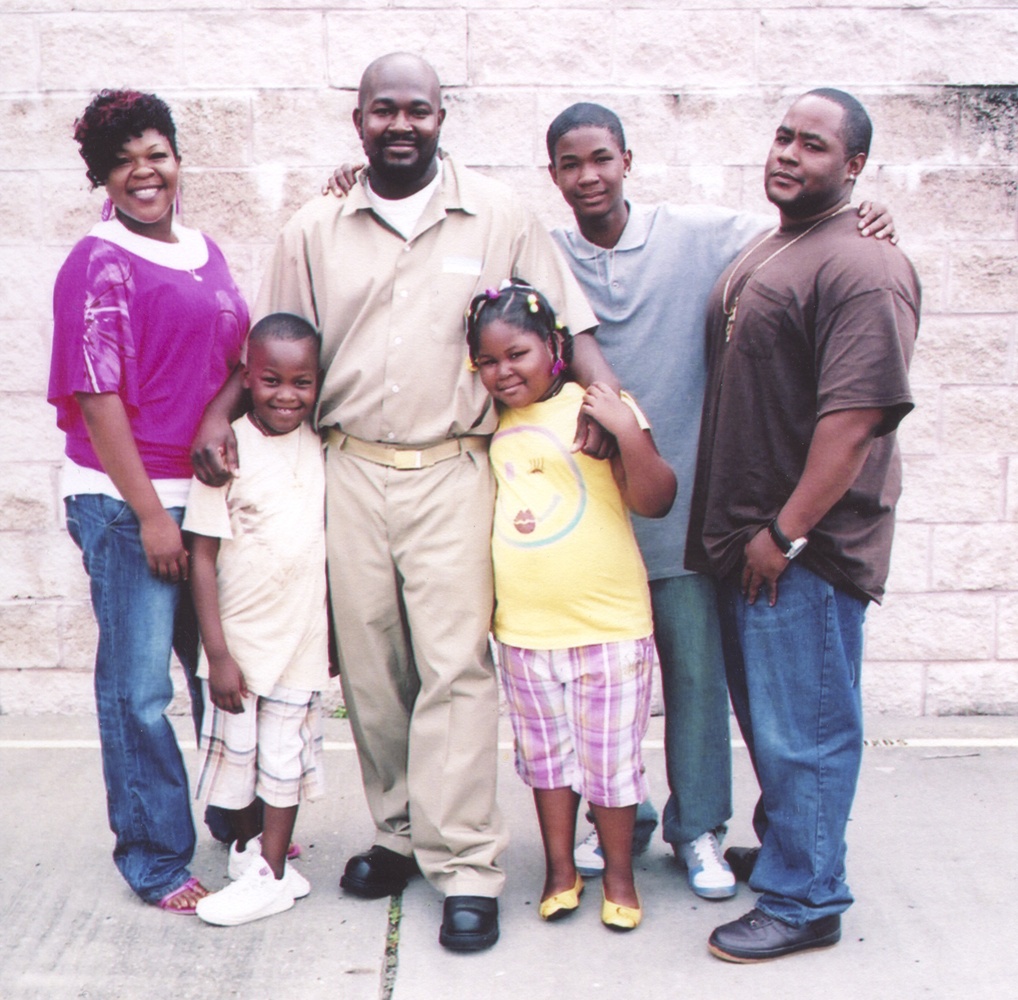

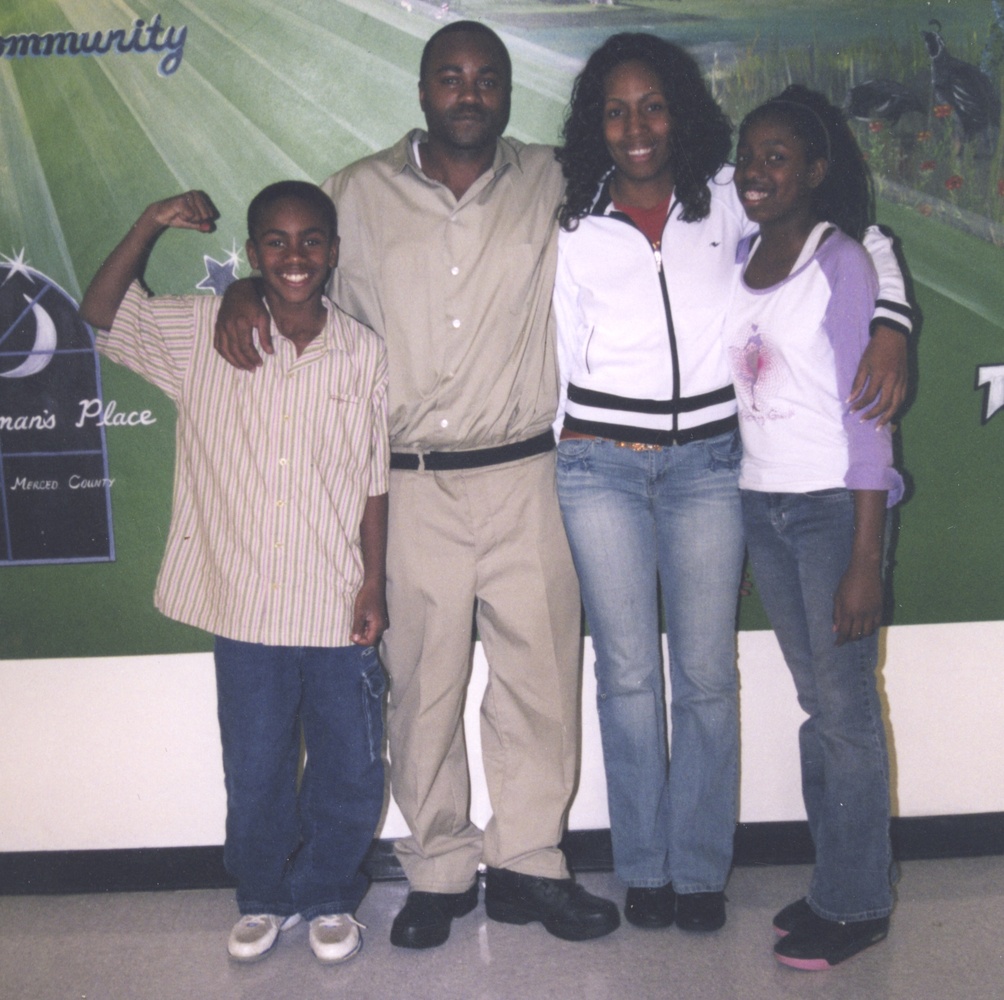

Michael Wilson

via ACLU

via ACLU

Michael Fitzgerald Wilson was sentenced to life

without parole as a first-time nonviolent drug offender in 1994. Former

President Bill Clinton commuted the sentence of the only white defendant

involved in the case in 2001.

Now 48, Wilson seldom sees his three sons, who are now in their mid-20s,

because they live in Texas and he's imprisoned in California. He

suffered a stroke in 2011 and his condition has improved very little.

-

Douglas Ray Dunkins Jr.

via ACLU

via ACLU

Had Douglas Ray Dunkins Jr. been selling powdered

cocaine instead of crack, he'd be out of prison by now. But the now

47-year-old has been behind bars for almost 22 years, sentenced to life

without parole for manufacturing and distributing crack cocaine when he

was in his early 20s.

Even the judge in his case, Terry R. Means, had misgivings about putting

Dunkins behind bars for so long. "It does seem unfair that the

guidelines bind me to give you a life sentence," he said at sentencing.

"It troubles me to think that you at your age [are] going to have to

spend the rest of your life in prison. It troubles me a lot."

-

Altonio O'Shea Douglas

via ACLU

via ACLU

Altonio O’Shea Douglas has been in prison for 20

years for his first and only conviction for conspiracy to possess and

distribute crack cocaine, possession with intention to distribute and

use of carrying a firearm during a drug crime. He was offered a

four-year deal to testify against his co-conspirators, but he didn't

want to go up against his relatives.

"It is very scary … to have to die in prison," Douglas told the ACLU.

"We all have to die one day, but you would like to die around your

family. You die in a place like this, you just die in a room by

yourself. It’s terrifying to think that this could possibly happen to

you."

-

Timothy Tyler

via ACLU

via ACLU

A vegan and a "Deadhead," Timothy Tyler was

sentenced to two mandatory life without parole sentences for conspiracy

and possession with intent to distribute LSD for mailing 5.2 grams of

the drug to a confidential informant. His life-without-parole sentence

was triggered because the judge counted not only the weight of the LSD

Tyler sent, but also the paper it was placed on, putting the amount over

the 10-gram threshold.

Tyler first became a regular LSD user after high school, when he

followed the Grateful Dead around to concerts and overdosed several

times, resulting in some time spent in mental health institutions. He

has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and came out as gay five years

ago, and he says he feared being a target of violence.

"Life, [the sentence] says, but life means you die in prison," he told the ACLU.

-

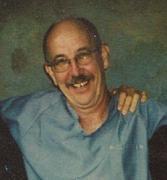

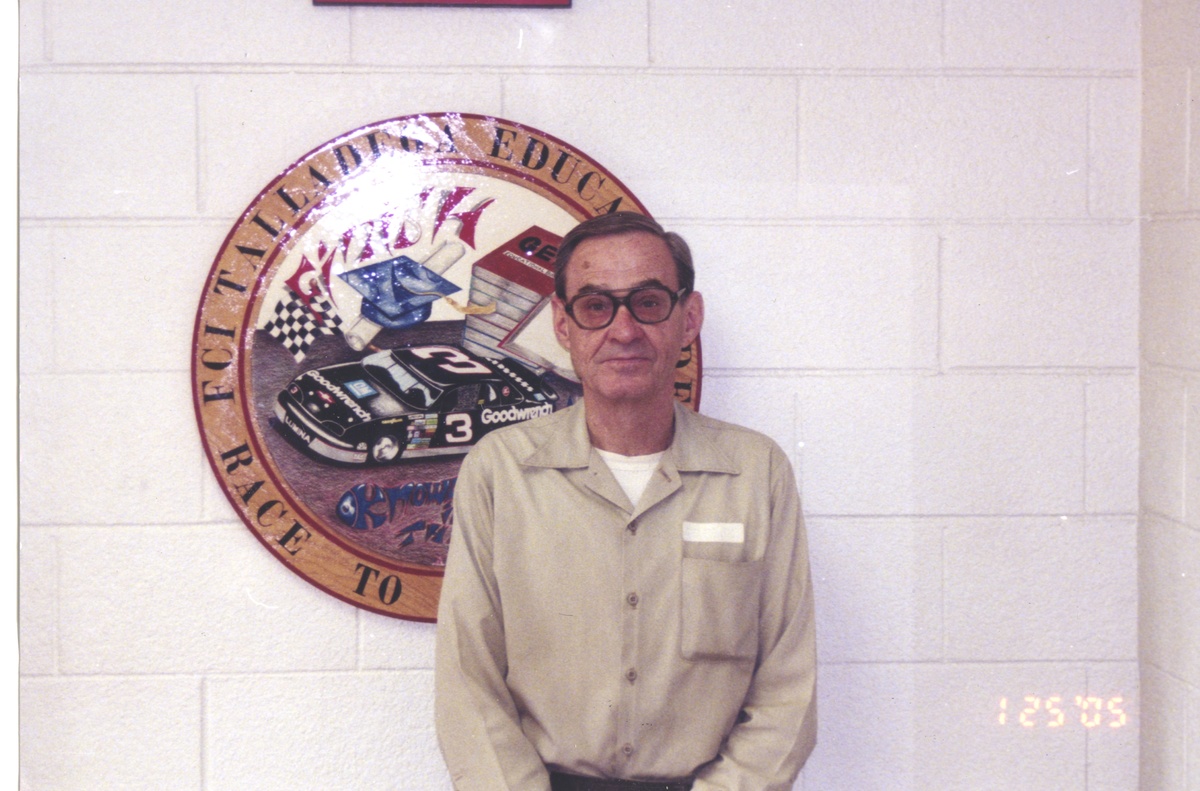

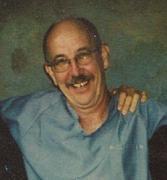

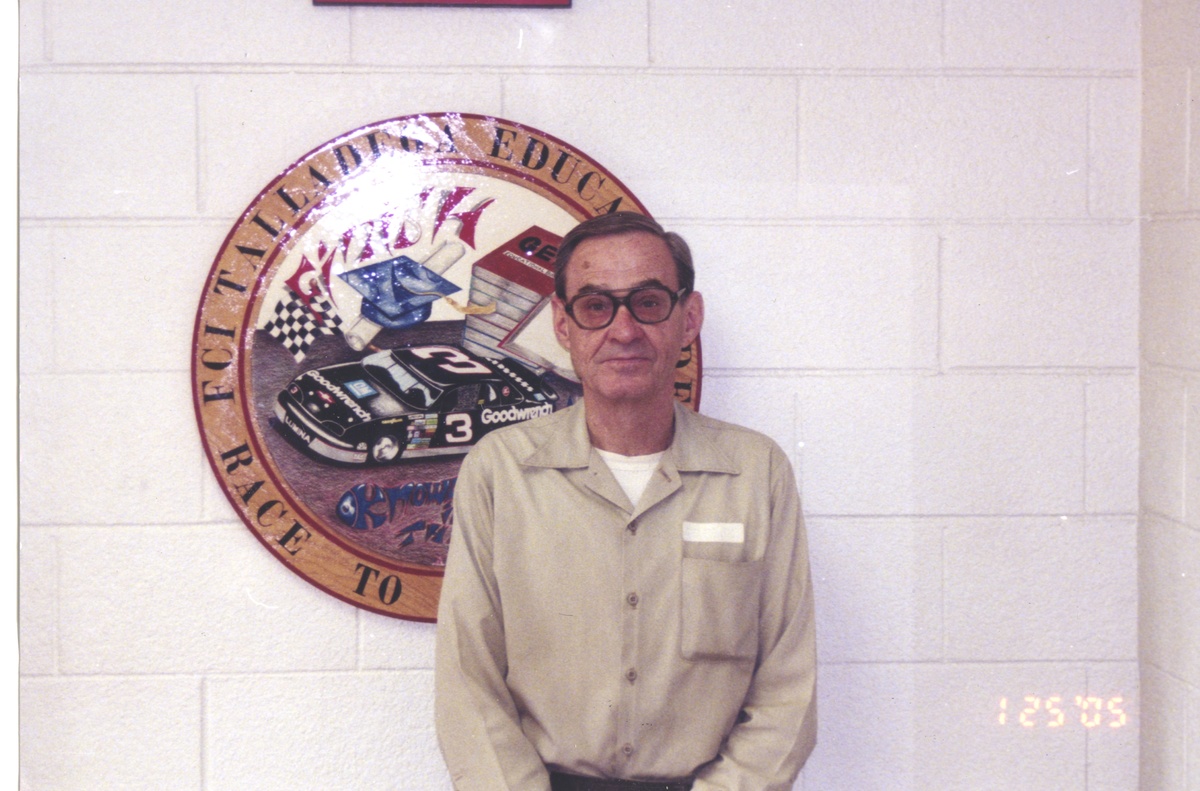

Larry Ronald Duke

via ACLU

via ACLU

Larry Ronald Duke, 66, has served 24 years in

federal prison out of his two life-without-parole sentences for

conspiring to possess with the intent to distribute more than 1,000

kilograms of marijuana. He and some co-conspirators attempted to

purchase a large amount of marijuana from a government informant who had

a prior marijuana arrest.

Duke served in Vietnam and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress

disorder. "I often thought I would probably die in a firefight in

Vietnam, and then later, I thought maybe I’d catch a streamer while

sky-diving and crash and burn," he told the ACLU. "Or perhaps, lose

control of a car at a very high rate of speed, but never in my wildest

dreams have I ever imagined I’d die in prison."

-

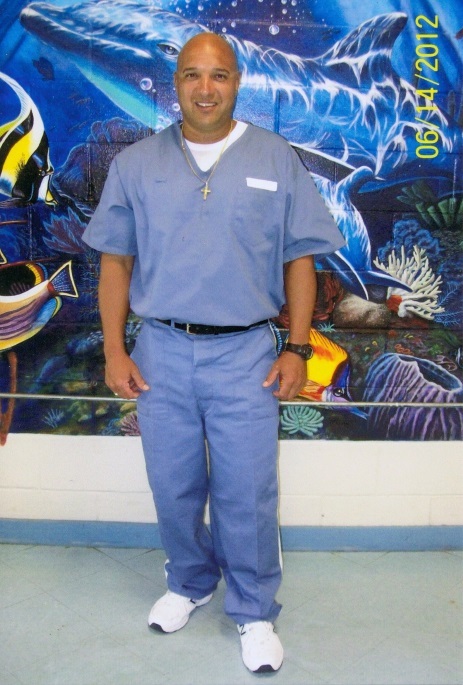

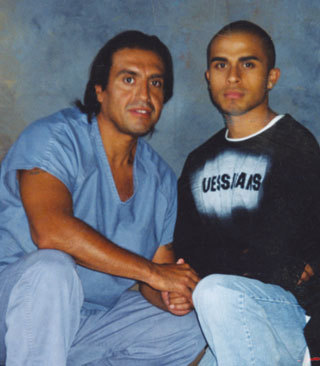

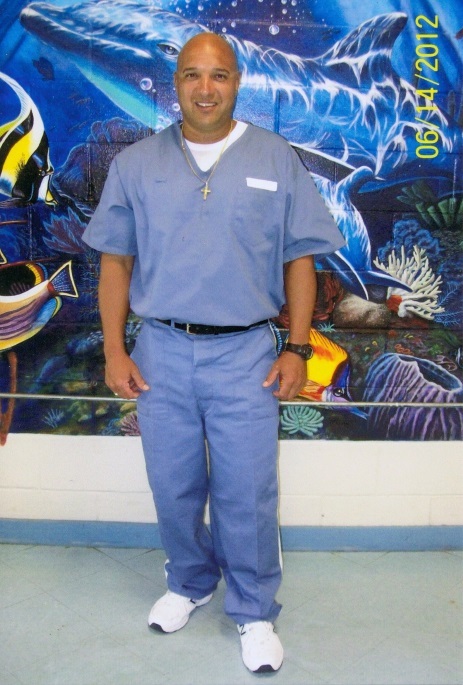

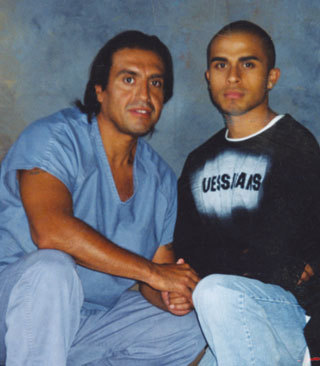

Roberto Ortiz

via ACLU

via ACLU

Ortiz was arrested for trafficking cocaine as part of a sting operation in 2001. It was his first offense.

In 2002, at the age of 31, he was sentenced to mandatory life without parole under the Florida Penal Code.

"When he told me his story and that he was in prison for life, I could

not believe it," one corrections officer who worked at Ortiz's prison

told the ACLU. "There [were] inmates that were in for rape or killing

someone that were getting out in 15 to 25 years. I had one inmate that

was drunk and ran a stoplight, hitting a van and killing six people,

including children, and only got 30 years, and he will be out in six

years due to earning gain time. I kept thinking [that] something is

wrong with this picture.”

-

William Dekle

via ACLU

via ACLU

Former Marine William Dekle, 63, has served 22

years of his two mandatory terms of life without parole for conspiracy

to import and possess large quantities of marijuana. He was sentenced in

1990, despite the trial judge characterizing the sentence as draconian.

His sentence is like a death sentence, but one without peace, Dekle told

the ACLU. "There are correctional officers and inmates here that were

not born when I started this sentence. How much more do they want? Is my

death here the only thing that will satisfy society?”

-

Clarence Aron

via ACLU

via ACLU

At 23, college student Clarence Aaron was

sentenced to three life-without-parole sentences for playing a minor

role in two planned large drug deals. He wouldn't testify against his

co-conspirators, but they testified against him and received reduced

sentences.

"At the time, neither Clarence nor I had any idea of how harsh a penalty

he would receive for this error," says his mother, Linda Aaron-McNeil.

"When the judge announced the sentence of three life terms, my heart

shattered into a thousand pieces. Since this nightmare began, I merely

exist. The pain never subsides."

-

Ricky Minor

via ACLU

via ACLU

Ricky Minor says he was a meth addict when he was

sentenced to life in prison without parole in 2001. Originally charged

on the state level after a tip from a confidential informant, Minor says

a prosecutor threatened to "bury" him in the federal system unless he

cooperated. He refused.

"The sentence … far exceeds whatever punishment would be appropriate.

... Unfortunately, it’s my duty to impose a sentence," Judge Clyde Roger

Vinson, a Ronald Reagan appointee, said at Minor's sentencing. "If I

had any discretion at all, I would not impose a life sentence. … I

really don’t have any discretion in this matter."

-

Steven Speal

via ACLU

via ACLU

Speal was sentenced to life in prison without

parole at the age of 25. He's now 42 and has been in prison for 17

years. He had two drug-related convictions at 18 and 19, and pleaded

guilty to possession of methamphetamine at the age of 22 after he was

arrested for riding in a car that was pulled over for allegedly making

an illegal U-turn, and police found methamphetamine, marijuana and

firearms inside.

His appeals process has been exhausted and his commutation petition was

denied in February of this year. "I know what I did was wrong but I did

not know any other way at the time, and I just wanted to be loved,"

Speal told the ACLU. "They gave us a death sentence because we made

mistakes when we were kids."

-

Donald Allen

via ACLU

via ACLU

Donald Allen was just 20 years old when he was

sentenced to two life-without-parole sentences. He says his

court-appointed lawyer did not provide adequate legal representation and

that he wasn't involved in the deal that resulted in his conviction on

conspiracy and possession charges.

-

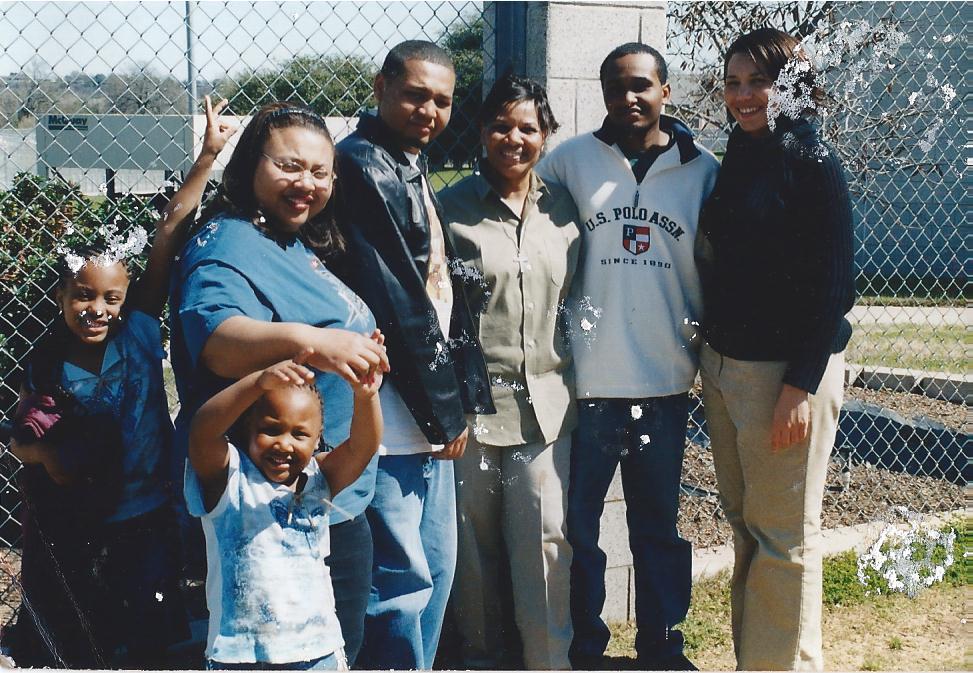

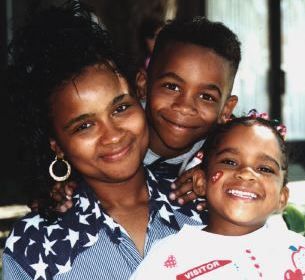

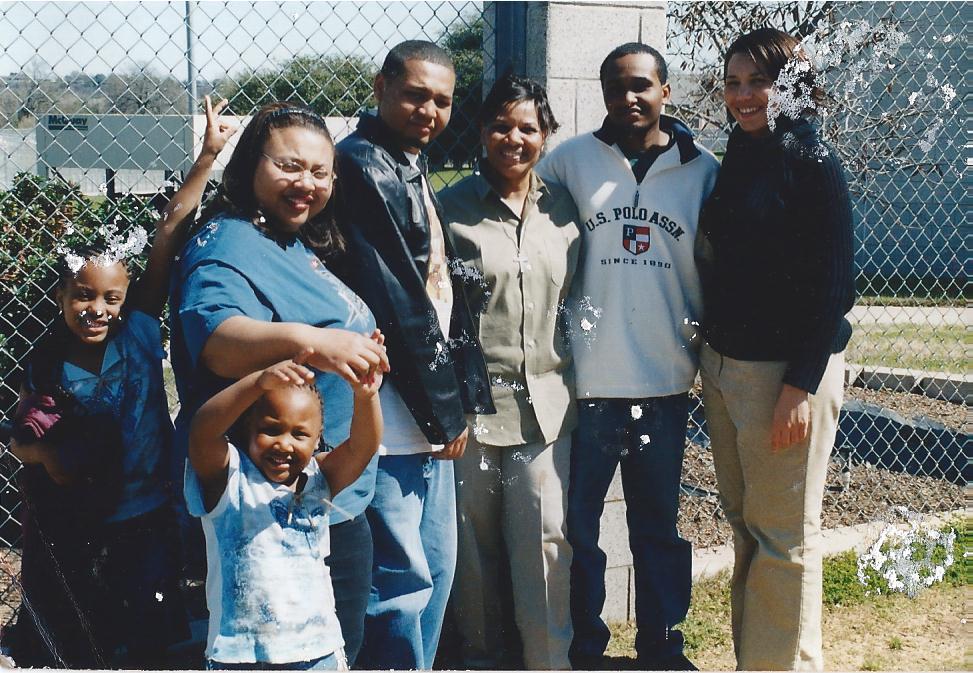

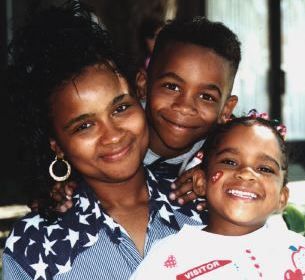

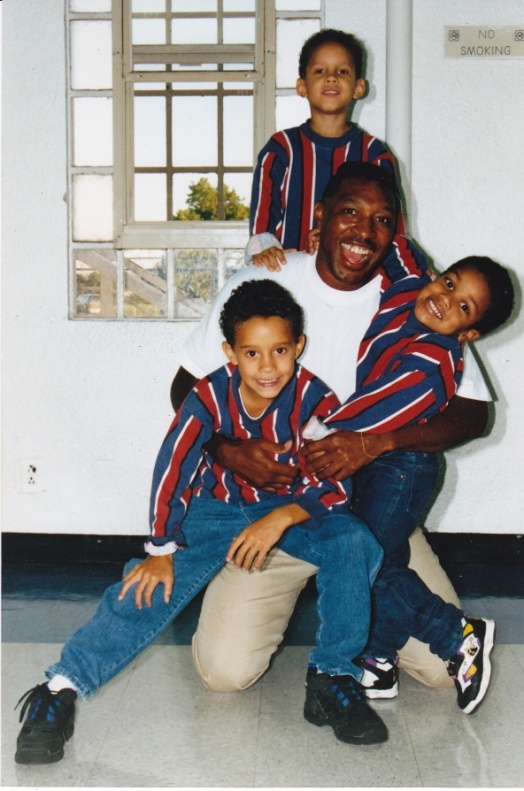

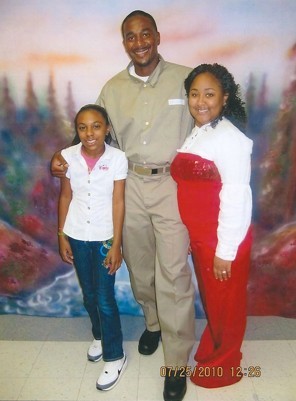

Sharanda Jones

via ACLU

via ACLU

Sharanda Purlette Jones is serving life without

parole for her part in a crack-cocaine conspiracy based almost entirely

on the testimony of her alleged co-conspirators. Jones was arrested as

part of a drug task force operation in Terrell, Texas, that netted 105

people. Actor Chuck Norris, who at the time was a volunteer police

officer for the Kaufman County Sheriff's Department, reportedly

participated in some of the arrests.

"I will expire in the federal system," Jones told the ACLU of her sentence. It is really a slow death."

-

John Knock

via ACLU

via ACLU

John Knock, 66, is a first-time offender serving

two life-without-parole sentences for participating in a marijuana

conspiracy in the early and mid-1980s. He was the target of a reverse

sting operation in 1993 by a former associate who had come under DEA

scrutiny. Though he said he had been out of the game for several years,

Knock was convicted of conspiracy to import and possess with intention

to distribute large quantities of marijuana.

"I have been separated from my family for 17 years. I have watched our

son grow from 3 into a young man of 22 through telephone calls and

prison visiting rooms. My life partner since 1974 is now my ex-wife,"

Knock, who is known as "the professor" in prison, told the ACLU. "When a

person goes to prison, the entire family pays the price. All do time of

some sort."

-

Leroy Fields

via ACLU

via ACLU

Leroy Fields was an unemployed 30-year-old father

of three when he was arrested in New Orleans in October 1999 for

possession of a stolen car. Fields borrowed the car from a friend and

didn't know it was stolen. He says his state-appointed attorney failed

to call the friend as a witness at his trial. He was sentenced to life

in prison under a three-strikes law because he had prior convictions,

one for possession of crack cocaine in 1993 and the other for simple

robbery for stealing a $90 pair of shoes in 1986, when he was 17.

"The court wrongfully took my life from me," Fields told the ACLU. "I

felt like there was no help for me, and I was expected to die here in

prison. And I still feel that … I’ll die here."

-

Teresa Griffin

via ACLU

via ACLU

Teresa Griffin was 21 years old, going to college

and working for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in Florida when

she says her boyfriend forced her to quit her job and follow him to

Texas. Five years later, she was sentenced to the equivalent of life for

conspiracy to possess and distribute cocaine through her boyfriend's

operation. She had no prior criminal record.

-

Charles Frederick Cundiff

via ACLU

via ACLU

Before his conviction, Charles "Fred" Cundiff had

worked at a plant nursery, in construction, as a mortgage solicitor and

as a stereo store manager. He was sentenced to life without parole for

importing and distributing more than 1,000 kilos of marijuana and has

been imprisoned since 1991.

He says the trial judge told him he would be sentenced to 15 to 20 years, but that such a sentence would be reversed on appeal.

Cundiff now has a variety of health problems and requires a walker. "If I

should die and go to hell, it could be no worse," told the ACLU.

-

Craig Cesal

via ACLU

via ACLU

Before he was arrested at the age of 42, Craig

Cesal's only conviction was a misdemeanor -- for carrying a beer into a

Bennigan's when he was a college student.

Cesal owned and operated a towing and truck repair business for 23

years. One of his clients was a trucking company whose truckers

trafficked marijuana.

Cesal was arrested for his alleged involvement in 2002, and believed he

would get a sentence of seven years if he pleaded guilty. He later tried

to withdraw his guilty plea because, he says, prosecutors wanted him to

testify against people he didn't know and two people who he thought

were innocent.

"In my case, those who did traffic marijuana received little or no

prison sentences and resumed their activities. They patronize a

different repair station now," Cesal told the ACLU. "I hope to die,

sooner rather than later."

-

Leopoldo Hernandez-Miranda

via ACLU

via ACLU

Now 74, Leopoldo Hernandez-Miranda was arrested

at age 55 for serving as a middleman in the shipping of a truckload of

marijuana.

He was new to Miami at the time and struggled to find work. "At the time

of my crime, I was willing to take a chance. Now that I know how a life

sentence feels, I would never take a chance with my life," he told the

ACLU.

-

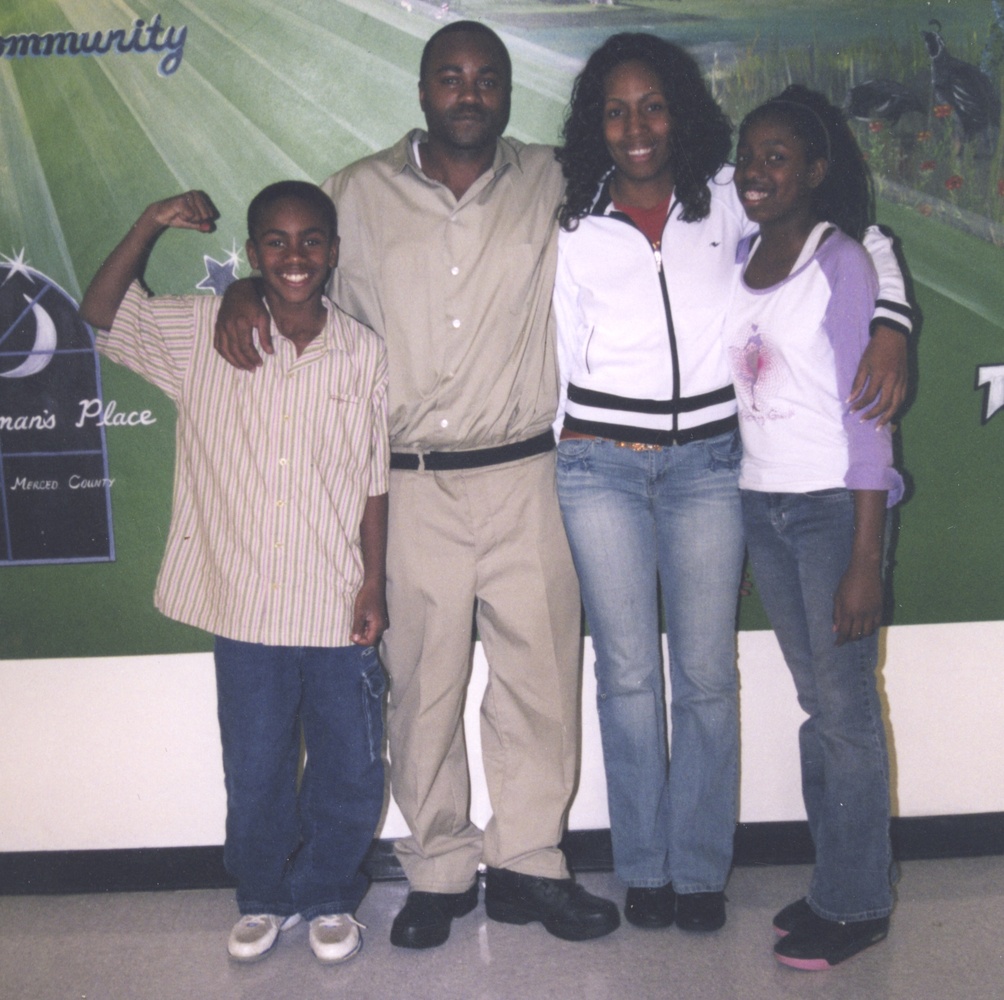

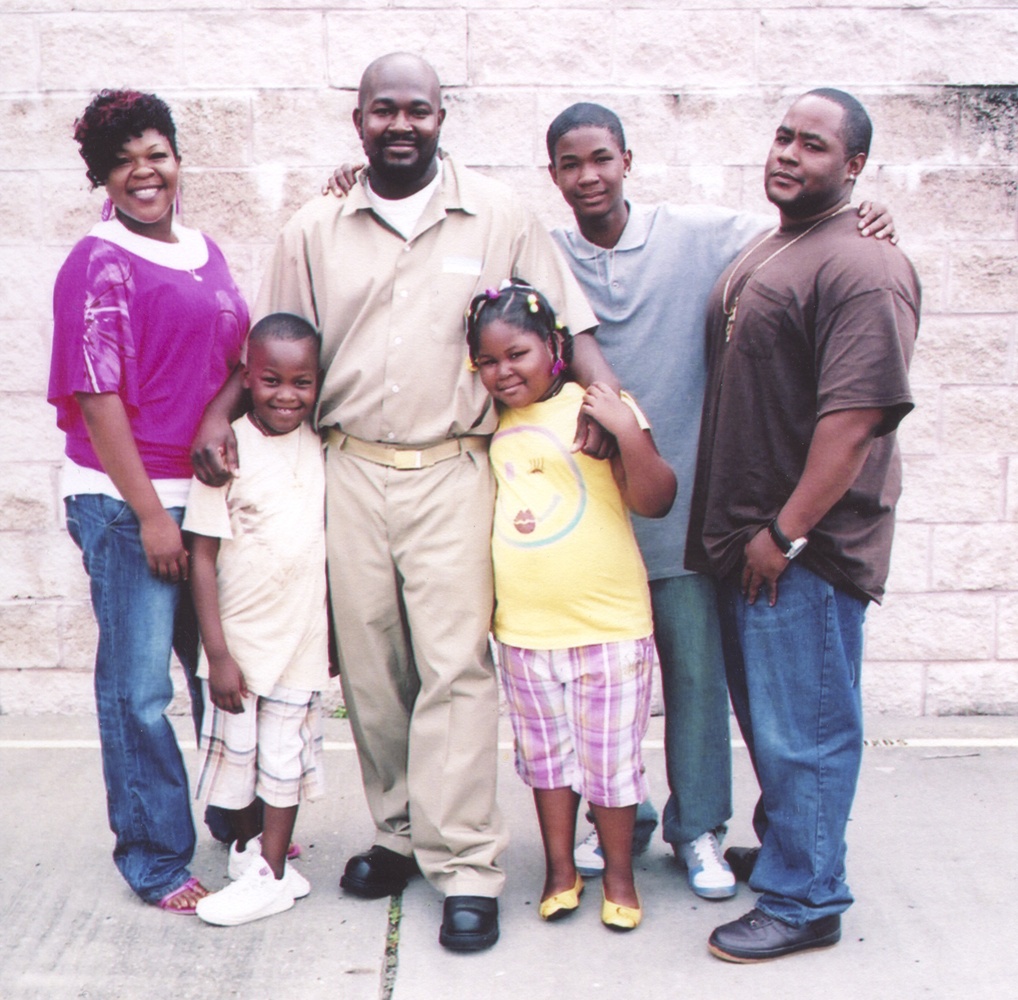

Reynolds Wintersmith Jr.

via ACLU

via ACLU

Reynolds Wintersmith Jr. has spent half of his

life in prison. He was arrested at 19 for dealing drugs and declined a

plea offer of 10 years, choosing to go to trial. He was only a street

dealer, but he opened himself up to the life-without-parole sentence

because he was held accountable for the entire amount of cocaine sold as

part of a conspiracy.

"This is your first conviction … and here you face life imprisonment. I

think it gives me pause to think that that was the intention of

Congress, to put somebody away for the rest of their life," the judge

said at his sentencing.

Wintersmith's commutation petition is pending, and his daughter has

asked President Barack Obama to give him "a second chance at life."

-

Robert J. Riley

via ACLU

via ACLU

Robert J. Riley was sentenced to life in prison

without the possibility of parole in 1993 for distributing LSD and

psychedelic mushrooms to other fans of the Grateful Dead.

The judge in his case counted the weight of the blotter paper on which

the LSD was dissolved, upping the total weight and triggering the harsh

sentence.

A George H.W. Bush appointee, the judge told Riley Congress was "keeping

me from being a judge right now in your case, because they’re not

letting me impose what I think would be a fair sentence." He later

called the sentence the harshest he'd ever given and said it brought him

"no satisfaction that a gentle person such as Mr. Riley will remain in

prison the rest of his life."

-

Scott Walker

via ACLU

via ACLU

Scott Walker got life without parole at the age

of 26. He had two prior convictions as a juvenile -- he stole a bike and

some aluminum gutters -- and had two adult misdemeanor convictions for

underage consumption of alcohol at 19 and criminal trespassing at 22.

Five hundred grams of marijuana were seized from him when he was

arrested in 1996. His co-defendants testified against him to get

reductions in their sentences.

"Since I was a child, I was taught that America was the land of

redemption," Walker told the ACLU. "But if you are a first-time offender

sentenced under a mandatory-minimum sentence, this is not the case.

Prison probably saved my life. I just hope I can get out someday to live

that life."

-

George Martorano

via ACLU

via ACLU

George Martorano believes he is the

longest-serving first-time nonviolent offender sentenced to life in

prison without parole in the federal system. He was arrested in 1982 at

the age of 31 and pleaded guilty, assuming he'd get 10 years at the

most. A sentencing report recommended around three to five years, but

the judge gave him life.

"When I came in, they called me 'the kid,'" he told the ACLU. "Now they call me 'pops.'"

-

Dicky Joe Jackson

via ACLU

via ACLU

Dicky Joe Jackson left school in 10th grade to

work in the trucking business with his father, and he soon began taking

methamphetamine to stay awake on long drives. In 1988, he was convicted

of possession of half a gram of meth, and the next year he was convicted

of transporting a kilogram of marijuana. He served a year in prison and

sold his truck to pay for legal fees.

While he was in jail, his 2-year-old son, Cole, was diagnosed with

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, a rare immunodeficiency disease. Soon, Jackson

owed $200,000 in medical bills, so he began transporting meth for a

supplier. In 1995, he sold half a pound of meth to an undercover officer

and received a mandatory minimum sentence of life without parole in a

federal prison. Now 55, he has been in prison for 17 years.

-

Rudy Martinez

via ACLU

via ACLU

Rudy Martinez got life in prison without parole

for his first conviction at the age of 25. He had started dealing

marijuana at 12 years old, and says he saw drug dealing as a way to

escape poverty.

Martinez says the alleged ringleader in his case, who ended up serving

less than three years in prison, has admitted that she lied about the

extent of his involvement in the conspiracy. All of his co-defendants

have been out of prison for more than a decade.

The judge in Martinez's case said the federal sentencing guidelines put "more trust in prosecutors than in federal judges."

"No words could ever fully describe the pain within when you know that

you will never spend any type of quality time with your children, for

the rest of their lives," Martinez told the ACLU. "I wish that on no

parent."

-

Stephanie Yvette George

via ACLU

via ACLU

Stephanie Yvette George was sentenced to life in

prison without parole at the age of 26 because of prior convictions for

selling small amounts of crack cocaine. The father of one of her

children used her attic to store cocaine and cash. Though George said

she didn't know the drugs were hidden in her apartment, six cooperating

witnesses testified that she was paid to store cocaine.

The judge wasn't allowed to consider George's minor role in the case.

"Even though you have been involved in drugs and drug dealing for a

number of years ... your role has basically been as a girlfriend and bag

holder and money holder. So certainly, in my judgment, it doesn’t

warrant a life sentence," he said at her sentencing. "I don’t really

have any choice in the matter. ... If there was some way I could give

you something less than life I sure would do it, but I can’t.

Unfortunately, my hands are tied ... I wish I had another alternative."

-

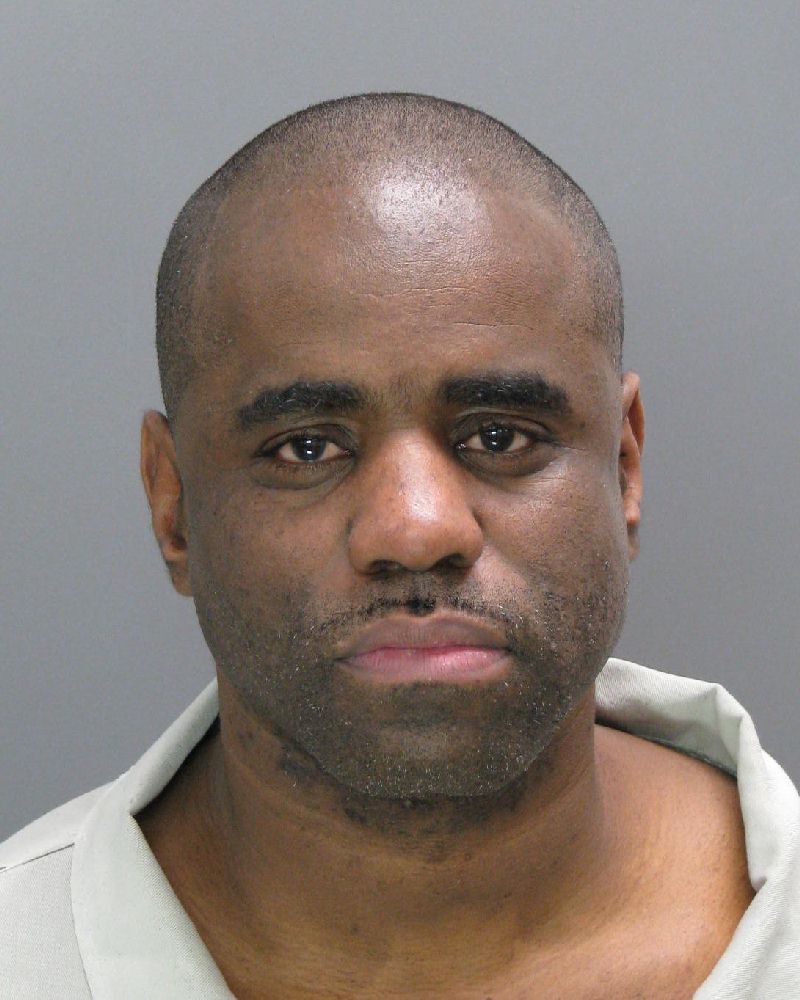

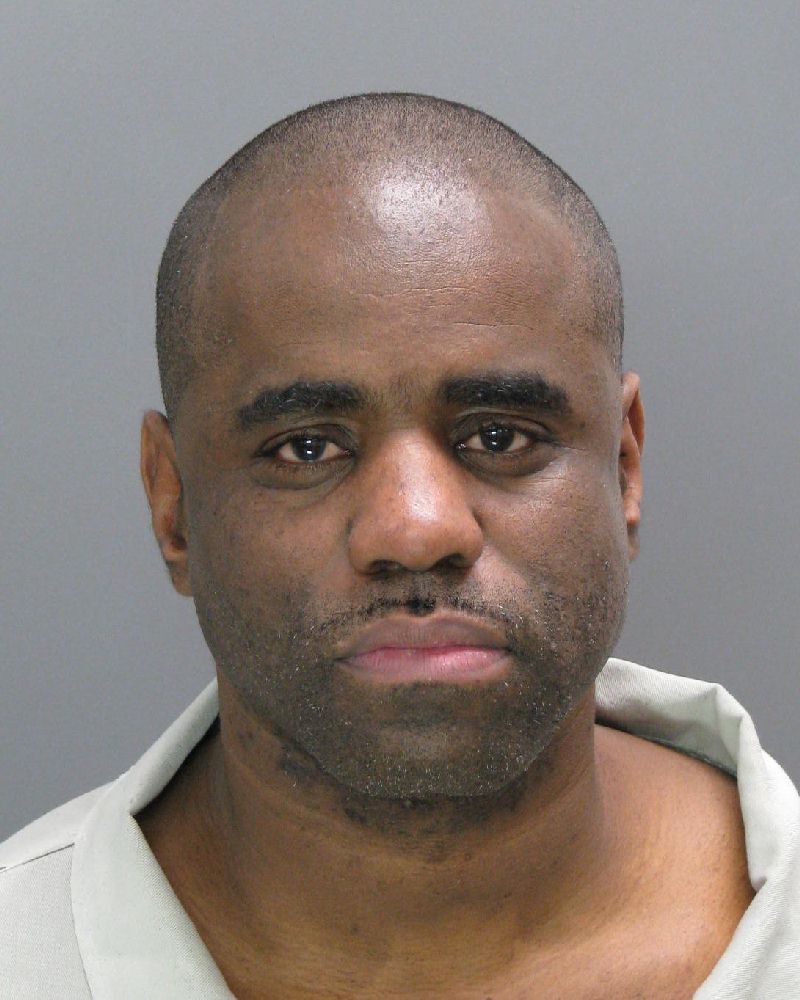

Anthony Jerome Jackson

via ACLU

via ACLU

Anthony Jerome Jackson's life-without-parole sentence came for stealing a wallet from a hotel room in Myrtle Beach, S.C.

Prior burglary convictions in 2006 and 2009 triggered South Carolina's

three-strikes law, and Jackson, now 46, says he didn't understand the

charges against him. "You will think that I kill[ed] someone with that

kind of time," he told the ACLU.

-

Robert Jonas

via ACLU

via ACLU

Robert Jonas served five years in prison for

selling cocaine when he was 46 years old. Six years later, he was

convicted of conspiracy to possess, import and distribute cocaine and

marijuana and sentenced to life without parole. Now 75, Jonas told the

ACLU that he passes the time in part by playing the trumpet and taming

wild cats. The report notes, "He has been written up for a single

disciplinary infraction: keeping a cat in his cell."

-

Jesse Webster

via ACLU

via ACLU

Jesse Webster was never actually convicted of

selling drugs. But in 1994, when he was still a teenager living on the

South Side of Chicago, he helped arrange a cocaine deal that was later

aborted. Months after that, he learned that the authorities wanted to

question him about the failed endeavor, so he turned himself in. Rather

than serve as an informant against a local gang that he wasn’t

affiliated with, he went to trial, where the jury found him guilty of

attempt and conspiracy to possess cocaine with intent to distribute and

filing false tax returns. He was sentenced to life in prison at 27 years

old.

"The world just got snatched out of me," he told the ACLU.

-

Clarence Robinson

via ACLU

via ACLU

When Clarence Robinson was 34, he was locked up

for life without parole for playing a minor part in a drug operation.

The jury had found him guilty of participating in the packaging of one

shipment of crack cocaine and of assisting more senior dealers with

"rocking up" -- turning powdered cocaine into crack.

Because he had two prior convictions for crack cocaine possession and a

conviction for possession of a firearm as a felon -- all crimes he

committed between the ages of 18 and 22 -- he was subject to a mandatory

life-without-parole sentence. Three higher-ups in the drug ring

testified against Robinson and received reduced sentences of nine to 10

years in exchange for their cooperation.

No comments:

Post a Comment