Scientists who study climate change and skeptics of human-caused global warming can agree on at least this: Global temperatures haven't risen nearly as much this century as model projections say they should have.

Source: weather.com/

Author: Terrell Johnson

At least, that's the way it looks today. But according to a recently published study in the scientific journal Earth's Future, the greenhouse gas-fueled heating of the planet hasn't stopped at all during the global warming pause or "hiatus" widely touted in recent years.

"Global warming is continuing, it just gets manifested in different ways," says Dr. Kevin Trenberth, a scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research who co-authored the study with NCAR's Dr. John Fasullo.

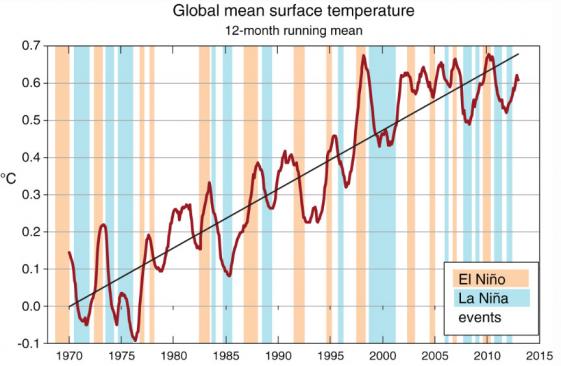

Since the 1970s, when scientists first began to detect the signal of a rapidly warming Earth against the background noise of natural variability, global temperatures spiked until about 1998. After that, warming began slowing down in big way, a trend that continues today:

Though warming didn't stop completely – global temperatures have risen by an average of about 0.05°C per decade since then, a far cry from the 0.15°C to 0.3°C per decade once projected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the slowdown has prompted climate change skeptics to claim we're actually in a period of global "cooling."

If you watched CNBC's Lawrence Kudlow show this week, you even heard commentators like Steven Hayward, a visiting scholar at the University of Colorado-Boulder, say things like this:

This has been a thorny question for climate scientists to answer, because humans have continued to pump ever-increasing amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. (Some studies have proposed that this is due to a lack of historical temperature data – more on that here.)

Trenberth acknowledged this – noting in an interview with weather.com, “the question is, where does that energy go, and how is it manifested?" – but added he and Fasullo found reasons to think global warming could begin to accelerate again soon:

1) Global averages hide a LOT of variation.

Most of the surface temperature slowdown has occurred only within a narrow band of time during the year, and only in certain parts of the world.

As this graph shows, the period from December through February has seen the sharpest slowdown, thanks in part to some big outbreaks of cold, wintry weather over the past few years in North America and Europe:

Plus, most of Earth's warming over the past 15 years has spared the subtropics and middle latitudes – which spans most of the U.S. and Mexico, as well as much of Eurasia – while areas like the Arctic have warmed dramatically, evidenced by the rapid shrinking of its late summer sea ice since the 1970s.

"There are these other signs of a warming planet," Trenberth notes, pointing out that melting has accelerated on Greenland's ice sheet and glaciers around the world. "One doesn’t just have to use the global mean surface temperature."

And as NCAR communications officer Bob Henson notes, "these two factors imply that what's been seen as a global pause in warming isn't really a worldwide phenomenon."

2) Human-produced greenhouse gases and natural variability work together.

The graph below couldn't be clearer: when El Niño is in effect, global temperatures tend to go up; when its close cousin La Niña dominates, it has a dampening effect on warming.

This is a key insight, because often skeptics claim that we can't blame global warming on human causes. Rather, they say, climate change should be chalked up largely – or only – to natural variability in weather and climate patterns.

Instead, Trenberth says the two can't really be separated. “There’s a tremendous amount of natural variability that goes on," he said.

“When human-induced climate change is influencing things in the same direction that the weather, or the natural variability, is already going – that’s when we break records," he added. "That’s when we really see the effects standing out."

3) The 1997-98 El Niño may have triggered the current warming pause.

When El Niño is in effect, it usually lasts only a year or two. But other ocean patterns, like the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, can last for periods of 20 or 30 years.

The PDO can have a big influence on El Niño and La Niña, Trenberth says, a fact that likely means it's largely responsible for the current warming pause. "There was a major phase change [in the PDO] in 1976, and from 1976 to 1998, the planet warmed," he said.

After the big 1997-98 El Niño, the oscillation changed from a warm to a cool phase.

"So that may have actually triggered the change," Trenberth added. “Since then, we’ve had more La Niña events, the cold events in the tropical Pacific ... under this negative phase, it tends to bury more heat deeper in the ocean, and so [warming] is not manifested as much at the surface."

That change in phase from positive (warmer) to negative (cooler) parallels the speed-up and slowdown in warming we've seen in recent decades:

4) The pause 'can't keep going on forever' – and perhaps not much longer.

No matter what phase it's currently in, sooner or later the PDO corrects itself and changes back. And there are signs that this may be about to happen soon, Trenberth says.

Globally, sea levels have risen about 2 1/2 inches since 1992. But in parts of the western Pacific like the Philippines – slammed by record-breaking Typhoon Haiyan last November – sea levels have risen over 8 inches, as PDO-influenced winds have driven a "piling up" of water there.

"At the same time, sea level has gone up less in the eastern Pacific," said Trenberth. “This can’t keep going on forever."

"It can’t continue to build up the sea level and the heat in one part of the ocean at the expense of another," Trenberth said. "At some point all of that water wants to slop back to the east – and so we start to go into this other phase."

That means there’s a slope in the global ocean across the Pacific that’s building up over time, he added. "And that’s what actually causes the end of these kinds of oscillations."

This year or later, it's possible that El Niño will occur again in the Pacific. Will that trigger another change in the PDO, that in turn could trigger a resurgence in global surface temperature warming? Only time will tell, Trenberth explained.

It all hinges on how long the imbalance in sea levels between the western and eastern Pacific can be sustained. "My suspicion is that it can’t go for that much longer," Trenberth said.

Original Article

Source: weather.com/

Author: Terrell Johnson

No comments:

Post a Comment