The Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa has warned that Venezuela's crackdown on anti-government street protests is a threat to democracy across Latin America.

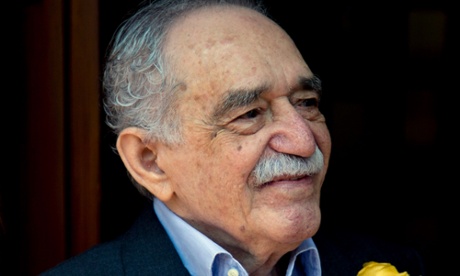

Latin American democracies are under threat because the goal of the Nicolás Maduro government is to expand, says Mario Vargas Llosa. Photograph: Jorge Silva/Reuters

Latin American democracies are under threat because the goal of the Nicolás Maduro government is to expand, says Mario Vargas Llosa. Photograph: Jorge Silva/Reuters

María Corina Machado has been one of the most visible leaders of opposition protests against President Nicolás Maduro. Photograph: Carlos Garcia Rawlins/Reuters

María Corina Machado has been one of the most visible leaders of opposition protests against President Nicolás Maduro. Photograph: Carlos Garcia Rawlins/Reuters

A member of Venezuela's national police fires teargas at anti-government demonstrators in Caracas this week. Photograph: Juan Barreto/AFP/Getty Images

A member of Venezuela's national police fires teargas at anti-government demonstrators in Caracas this week. Photograph: Juan Barreto/AFP/Getty Images

Fidel Castro, left, with his brother Raúl, right, and the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, centre, in Havana. Photograph: Reuters

Fidel Castro, left, with his brother Raúl, right, and the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, centre, in Havana. Photograph: Reuters

Former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2009. Photograph: Karel Navarro/AP

Former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2009. Photograph: Karel Navarro/AP

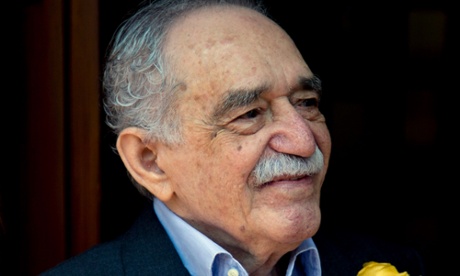

The Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who Mario Vargas Llosa has not spoken to in almost 40 years. Photograph: Eduardo Verdugo/AP

The Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who Mario Vargas Llosa has not spoken to in almost 40 years. Photograph: Eduardo Verdugo/AP

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Dan Collyns in Lima

In an exclusive interview with the Guardian, the Nobel laureate saidNicolás Maduro's government was becoming a "messianic dictatorship" intent on spreading its influence across the region.

"If the regime in Venezuela crushes the resistance and becomes a totalitarian regime, I think all democratic Latin American countries would be threatened because the explicit goal of the Venezuelan government is to expand," he said from his home in the Peruvian capital, Lima. "As our democracies are quite fragile and weak this threat is extremely worrying because it can succeed."

The 78-year-old lambasted the Organisation of American States' response to the crisis in Venezuela as "absolutely unacceptable", adding that the "logical reaction from democratic governments [which make up the OAS] would be a very strong condemnation of what is going on in Venezuela".

The pan-American body has barely debated the crisis in Venezuela. Last month, María Corina Machado, a Venezuelan opposition leader, tried to address the OAS as a temporary member of Panama's delegation. But two-thirds of OAS members voted to bar the media from the session at which she spoke. The vote was widely seen as an attempt to avoid offending Maduro.

Thirty-nine people have been killed and more than 600 injured in clashes between Venezuela's security forces and anti-government protesters, who are angered by soaring crime, rampant inflation and food shortages in the country. The unrest began more than 10 weeks ago with student-led protests in the western city of San Cristóbal and had since spread to other cities, including the capital, Caracas.

On Tuesday, Maduro told the Guardian that the US was fomenting the unrest as a way of taking control of Venezuela's oil reserves. Washington denies any role in the protests and says the Venezuelan government has used them as an excuse to crack down on political opponents.

Vargas Llosa, who was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2010, was a vocal critic of Maduro's predecessor, Hugo Chávez, with whom the author had several barbed exchanges, once turning down an invitation to appear on the late leader's television show Alo Presidente if he could not directly debate with him.

Vargas Llosa has aired his outspoken political opinions almost as long as he has been an author. In a career spanning more than 50 years, he has gone from being part of a generation of young Latin American writers who supported the Cuban revolution to becoming one of its harshest critics.

"Today everybody is more or less conscious of the total failure of the Cuban revolution to produce wealth, to produce a better standard of living for the Cubans. With the exception of small radical parties … Latin Americans know that it's a brutal dictatorship and the longest in Latin American history," he said.

He said Fidel Castro belonged to the past, adding: "My impression is the Cuban revolution will fade away little by little."

Vargas Llosa has long been a self-declared defender of liberty and enemy of dictatorships – a theme he tackles in two of his most acclaimed works. In Conversation in the Cathedral (1969) he chronicles the Peruvian military dictatorship of Manuel Odría through the eyes of a frustrated young journalist. The brutal three-decade dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) in the Dominican Republic is explored in The Feast of the Goat (2000).

But the new generation of Latin American writers, he said, are far less concerned with politics. "There are so many new young poets, novelists and playwrights who are much less politically committed than the former generations. The trend … is to be totally concentrated on the literary aesthetic and to consider politics to be something dirty that shouldn't be mixed with an artistic or a literary vocation," he said.

"For us, it was inconceivable to write and be completely disinterested in political matters but that was probably because when we were young what we had were military dictatorships."

That reluctance to mix art and politics reflects the region's growing democratic and economic stability, Vargas Llosa says. The writer made a disastrous foray into Peruvian politics as a candidate in 1990 presidential elections. He lost to Alberto Fujimori, who was later jailed for corruption and for authorising death squad killings during his decade in office.

Almost a quarter of a century later, Vargas Llosa describes his run for the presidency as an instructive experience, adding that he did not have either the "virtues or vices of a real politician" to have succeeded.

But the author continues to participate in the political debate in his country, considering it a "civic responsibility". In spite of his reputation as a political conservative he has attracted the opprobrium of religious groups by backing a campaign to decriminalise abortion in the case of rape. Abortion is illegal in Peru as in most of Latin America. He is also an outspoken supporter of gay rights in the Catholic country, backing a bill in favour of civil union.

At 78, he continues to write every day and maintain a convivial public life. "I don't want to finish my life not being alive. I think that is the saddest thing that can happen to a person … I want to keep living to the end," he said.

With his second wife, Patricia, and the mother of his three children, he shares the bulk of his time between his property in Madrid and his apartment in Lima, which contains his 30,000-book library and overlooks the Pacific Ocean.

"I work very hard, you know … but I don't think that I'm working because what I do pleases me so much," he said, adding: "I write about certain things because certain things happen to me."

This perhaps does not explain some of his more fantastical characters, from mad dictators to manic scriptwriters to a doomsday preacher in The War of the End of the World (1984), and a body of work that spans weighty epics, romantic comedies and confessional essays and has been translated into 30 languages. His legacy in Latin America is only rivalled by his fellow Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez, whom he famously punched in 1976 in Mexico City in one of the 20th century's greatest literary rows.

They have not spoken since and the reason remains a mystery although it is rumoured to have had something to do with Vargas Llosa's wife. García Márquez, 87, who no longer writes and has dementia, wasreleased from hospital on Wednesday after being admitted for pneumonia. Vargas Llosa said the Colombian author's writing was one of the "real important literary works of this time.

"One Hundred Years of Solitude is one of the great achievements in literature and that will be his legacy."

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Dan Collyns in Lima

No comments:

Post a Comment