WASHINGTON -- The Obama administration and the scientific community at large are expressing serious alarm at a House Republican bill that they argue would dramatically undermine way research is conducted in America.

Source: huffingtonpost.com/

Author: Sam Stein

Titled the “Frontiers in Innovation, Research, Science, and Technology (FIRST) Act of 2014," the bill would put a variety of new restrictions on how funds are doled out by the National Science Foundation. The goal, per its Republican supporters on the House Science, Space and Technology Committee, would be to weed out projects whose cost can't be justified or whose sociological purpose is not apparent.

For Democrats and advocates, however, the FIRST Act represents a dangerous injection of politics into science and a direct assault on the much-cherished peer-review process by which grants are awarded.

"We have a system of peer-review science that has served as a model for not only research in this country but in others," said Bill Andresen, the associate vice president of Federal Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania. "The question is, does Congress really think it has the better ability to determine the scientific merit of grant applications or should it be left up to the scientists and their peers?"

In recent weeks, the Obama administration and science agencies have -- in less-than-subtle terms -- offered up similar criticisms of the FIRST Act. At an American Association for the Advancement of Science forum on Thursday, presidential science adviser John Holdren said he was "concerned with a number of aspects" of the bill.

"It appears aimed at narrowing the focus of NSF-funded research to domains that are applied to various national interests other than simply advancing the progress of science," Holdren said.

Meanwhile, in a show of protest that several officials in the science advocacy community could not recall having witnessed before, the National Science Board released a statement in late April criticizing the bill. As the oversight body to the National Science Foundation, the NSB traditionally stays out of legislative fights. So when it warned that the FIRST Act could "significantly impede NSF's flexibility to deploy its funds to support the best ideas," advocates said they were surprised and pleased.

"The fact that the NSB commented on legislation, I don’t know if it is unprecedented but it is at least extremely unusual," said Barry Toiv, a top official at the Association of American Universities. "And we think that speaks to the really serious problems posed by the legislation."

And yet, for all the concerns with the FIRST Act, it seems unlikely that the bill's main author will incorporate additional changes. Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), who chairs the House science committee, decided early on that he would take a different approach to re-authorizing science research funding. Instead of passing an updated version of a 2010 bill that funded four agencies under the committee's purview, he chose to split the bill in two and offered two years of funding, as opposed to four years. From that decision came the FIRST Act.

The bill actually increases funding for the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Science Foundation by 1.5 percent in fiscal year 2015. But while that may seem like a good deal for agencies suffering the lingering effects of sequestration, it fails to keep pace with inflation and falls well short of the 4.9 percent increase that Democrats wanted.

Smith, as reported by the Boston Globe, also chose to significantly tighten the regulations on how the money in the bill would be allocated. For example, the bill would require the NSF to ensure that one grant recipient didn't receive a grant from another federal agency for research with the "same scientific aims and scope." The idea was to prevent double dipping. But advocates warn that it could dry up funds for research with multiple components.

Another part of the bill stipulates that if an investigator receives more than five years of funding from the NSF, he or she can only get additional funding by contributing "original creative, and transformative research under the grant." Ensuring that the government doesn't plow resources into stalled projects may be laudable. But scientists shudder at the idea that they, let alone politicians, can definitively tell whether research will pay dividends after half a decade.

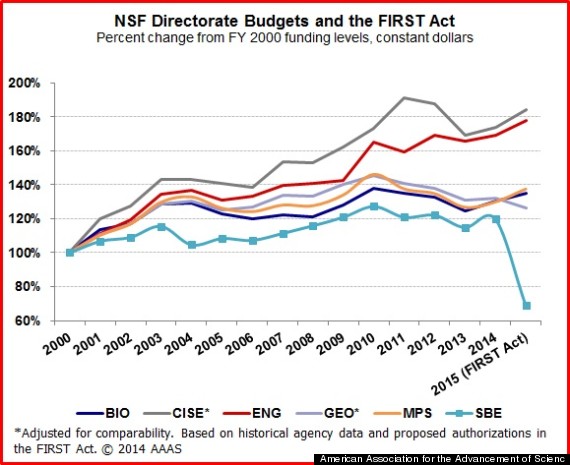

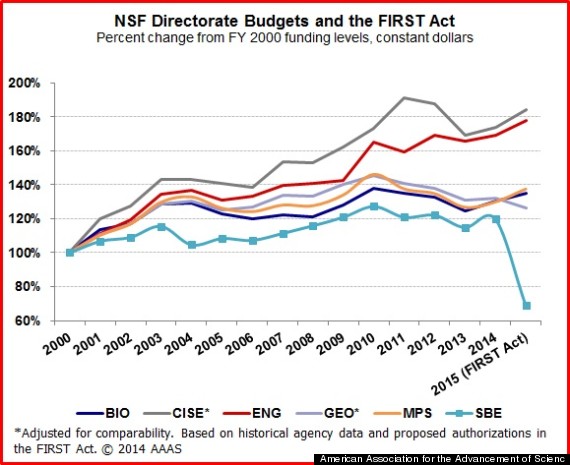

These quips merely feed a larger problem that Democrats and the White House have with the bill. Rather than offering a single budget level for the NSF, the FIRST Actauthorizes levels for individual directorates, or sub-agencies, within the foundation. The big winners in this equation are the Directorate for Computer & Information Science & Engineering and the Directorate for Engineering. The loser is the Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences Directorate, which is poised to get a 22 percent budget cut from fiscal year 2014 levels.

Smith has shown no discomfort with that decision. In fact, he and others on the committee have pushed Democrats and Holdren to justify some of the social science projects that have received federal funding, such as $340,000 to study the ecological consequences of early human-set fires in New Zealand, or a 3-year, $200,000 study of the Bronze Age on the island of Cyprus.

"What is broken is NSF’s refusal to provide Congress and American taxpayers with basic information about how NSF-funded grants are in the national interest," Smith said in a statement to The Huffington Post. "President Harry Truman vetoed the first NSF-enabling legislation because he concluded it didn’t protect taxpayers’ right to know about how the agency would spend their money. It’s unfortunate that the President’s Science Advisor would rather provide NSF with a blank check than set basic standards of transparency. The NSF’s cornerstone remains solid, but its boarded up windows are what need repair."

Democrats have objected that this is, in essence, an injection of politics into science.

But Smith's line of argument has worked before. In 2013, Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) pushed an amendment requiring that NSF grants for political science go only to projects that fostered national security or economic development. Applicants protested, arguing that politicians weren't equipped to judge the merit of their work. They also argued that their projects were being portrayed as quackery when they actually had immense utility. But when the amendment passed, they adjusted their applications appropriately.

Advocates are now hoping to avoid a rerun. Smith has yet to bring the FIRST Act to the floor before the science committee, in part because it's unclear if he has the votes. Democrats are expected to oppose the measure en masse, with the possible exception of one or two members. Some Republicans, meanwhile, are likely to vote no because of the higher funding level it includes.

Needing to thread the needle, Smith could make a strategic gamble. Since the House appropriators have already indicated support for higher levels of NSF funding -- and since the science committee's authorization has to ultimately be approved by the appropriations committee –- advocates expect him to woo Democrats with more NSF money while keeping the policy elements of the bill in place in order to placate his own party.

The science community would be put on the spot -- just what is the price for allowing political meddling in their field?

"Our concerns with the bill are both in funding levels and policy," said the University of Pennsylvania's Andresen, indicating that he and others would be tough to buy off. "And our policy concerns are fundamental and serious and it would lead us to oppose the bill."

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.com/

Author: Sam Stein

No comments:

Post a Comment