Many Canadians have a love-hate relationship with the energy sector.

Source: huffingtonpost.ca/

Author: cbc

We love it for the jobs but hate the fact that Canada is often seen as a climate change villain, whether the description is fair or not.

But just how much does the Canadian economy, especially the job market, depend on the energy sector?

CBC News asked the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary to run some numbers and the answer is a lot.

Economist Ron Kneebone created an alternate reality of Canada’s job market — one in which Alberta wasn’t booming. Specifically, if the province’s job market over the past 20 years grew at the same rate as Ontario’s.

It’ll come as no surprise that Alberta has the highest employment growth in the country.

Since 1995, its employment has grown by an average 2.5 per cent a year — considerably faster than Ontario, which had the next highest growth rate of 1.44 per cent.

Unemployment numbers

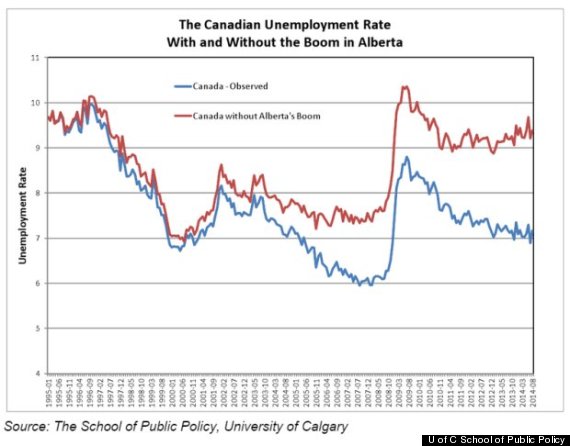

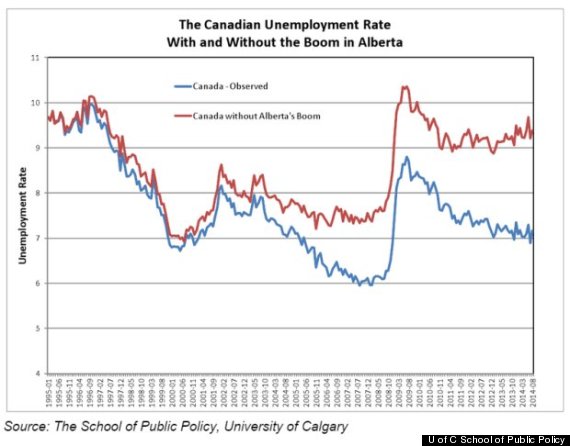

Kneebone tried to answer just what would the Canadian unemployment rate be today if it had not been for the boom in job creation in Alberta.

Obviously the number would be higher, but how much higher?

“By August 2014, the unemployment rate that we observed in Canada (7.165 per cent) would have been 9.39 per cent,” said Kneebone. “That is a 2.2 percentage point difference.”

That difference translates to 411,000 fewer jobs in Canada in 2014.

National Process Equipment is one of the companies that’s been creating some of those jobs. The company produces pumps and other equipment that moves fluids, something that is much in demand in the energy industry.

Dave Harvey, vice-president of marketing for the company, says things really took off at its Alberta operations over the past five years.

His company’s revenues jumped by 45 per cent and employment in his Calgary plant by nearly 50 per cent.

“These are skilled jobs,” said Harvey. “Whether it’s on the shop floor, whether they’re tradespeople, or engineers in the front office drawing up plans, or accountants, these are good lifetime jobs.”

Energy boom variables

Kneebone describes his analysis as a back-of-the-envelope calculation that doesn’t take into account all of the variables of the energy boom.

For instance, fewer jobs would be created in other provinces if Alberta wasn’t booming. Also fewer people would have migrated to the province and fewer temporary workers would have entered Canada.

Those factors would have an effect on his experiment and hypothetical unemployment rate.

As well, if investment dollars didn’t flow into the oil patch, presumably they would have gone elsewhere.

So the number isn’t exact, but it’s no great leap to acknowledge that without the oil boom, Canada’s economy would not be doing as well as it is.

The graph above shows the observed national unemployment rate (blue) as well as the unemployment rate without Alberta’s boom (red) that Kneebone modelled in his experiment.

The two lines really begin to diverge in 2002 around the time that we saw the beginning of the oil boom.

Oil prices

In 2002, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) — the North American benchmark — traded around $20 US a barrel. Two years later, it had nearly doubled to $40 US a barrel.

In 2006, WTI traded at $60 US a barrel, and then $140 US a barrel in 2008. You can see that the two unemployment rates tend to move apart and come back together depending on the price of crude oil.

The graph ends in August 2014, which also marks the beginning of a substantial price drop for crude oil.

At the beginning of August, WTI traded above $95 US a barrel. This Tuesday it closed at $77.40

A multitude of reasons is dragging down the price of oil: increased supply in the U.S. and Saudi Arabia lowering its prices for the U.S. market to protect market share.

As of now, the drop in the price of oil is being offset by a corresponding drop in the Canadian dollar, the currency in which WTI is priced, but alarm bells are being raised.

Could the boom be coming to an end?

Late last month Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz said if oil remains low, it will shave a quarter point off Canada’s economic growth, which is forecast to come in at 2.5 per cent this year.

Poloz said it was enough of a hit to have him worried.

Peter Jarrett, a Canadian economist with the OECD, says we might already be seeing signs of Alberta’s slowdown.

“We saw monthly building permits from StatsCan come out (last week) and where are the permits the strongest? Ontario. Toronto and Ottawa in particular," he said. "Where are they not doing well? Alberta, among other places. Building permits are not activity yet, but they are intention.”

Jarrett says if oil prices remain low, there will be a profound impact seen as soon as next year.

“There will be people who may have nothing to do with the oil and gas industry who have taken out loans, built factories that are predicated on Alberta still growing three to four per cent per year and attracting immigrants and migrants from Eastern Canada. If those flows from abroad and Eastern Canada stop and go into reverse, there will be a lot of pain to be felt.”

Harvey says his company, National Process Systems, is not as concerned — at least for now.

"This industry makes decisions for the long term, not for the short term. We’re certainly bullish, we think industry will continue to grow, we’re certainly going to invest in it. It’s been a great ride and I hope it continues.”

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.ca/

Author: cbc

No comments:

Post a Comment