Ever since oil prices began collapsing in the second half of last year, many in Canada have been asking: Can our economy survive without oil?

That question is harder to answer these days than it used to be. In previous oil price collapses, Canada didn’t suffer too badly (though the West, obviously, took major hits), but this time around, the country is more dependent on energy exports than it was in the past, and the picture is a little murkier.

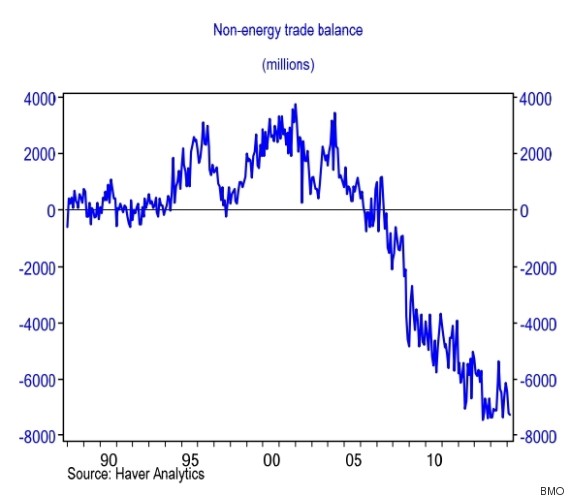

In a note last week, the Bank of Montreal gave us an indication of how things stand with a chart that looked at Canada’s trade balance (imports and exports) with energy stripped out.

It wasn’t a pretty picture.

Canada’s non-energy trade has been falling for more than a decade, slipping into deficit territory around 2006 and staying there ever since.

Our trade deficit with the rest of the world widened to a record high of $3.02 billion in March, but strip away energy — where we have a trade surplus — and that trade deficit balloons to $7.3 billion.

That’s “very close to the biggest gap on record, reinforcing that non-energy trade still has lots of room to improve,” BMO economist Benjamin Reitzes wrote.

Part of what has allowed this trade deficit to grow as large as it has is the fact that Canadian consumers keep on buying, despite the fact that Canada is selling less to the world. Reitzes notes that imports grew 2.2 per cent in March, led by a 7.9-per-cent surge in consumer goods imports.

“No signs here that Canadian consumers are taking a breather despite the big drop in oil prices and what appears to be a soft economic backdrop,” he wrote.

That has some economists worried.

“Although deficits of this magnitude have been reached before, what concerns us is this time is the growing household imbalances that are underpinning this shortfall,” wrote David Madani of Capital Economics, which has been warning for years about Canadian consumers over-stretching their finances.

A lower loonie was supposed to help this situation, and many economists are preaching patience on that front (“it will take some time for the weaker currency to have a sizeable impact on trade,” BMO’s Reitzes says) — but Madani thinks the problem will be fixed differently.

“Unfortunately, the most likely scenario is that the current account deficit will be closed mainly through a very painful decline in household net borrowing, which depresses domestic demand and imports.”

DO WE HAVE ANYTHING ELSE TO SELL?

The optimistic scenario is that Canada will start selling more. But Madani estimates exports would have to rise by nine per cent over levels at the end of last year to close that deficit — and that seems unlikely.

And part of the problem — as has been suggested before — is that Canada may not have as much to sell to the world as it used to, thanks to that growing reliance on oil.

Prominent economist Tyler Cowen of George Mason University has suggested Canada is being left behind in the 21st century’s “knowledge economy.”

“At this point [it] seems likely … that Canada will not be a huge innovative part of the knowledge economy,” he said in an interview while in Toronto.

Cowen said trying to make places like Waterloo, Ontario's tech hub into a new Silicon Valley may be pointless — because Silicon Valley already exists, and creating a competitor may just not work. Still, he suggested that those lower oil prices will in effect force Canada to diversify its economy -- which “may in the long run be a blessing.”

“It will force people to re-gear now while they still can, rather than becoming so undiversified that years from now it will be much harder,” Cowen said.

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.ca/

Author: Daniel Tencer

No comments:

Post a Comment