Choppy waves on Shoal Lake rock a small, beached motor boat as two young men haul its load of 20-litre water jugs into a waiting pickup. A few minutes' drive up a dirt road, and the water is delivered, jug by jug, to what used to be the local youth centre. Now this big block of a building is home instead to every drop of drinking water for the 322 residents of the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, after the floor of their water storage shed buckled and collapsed.

Waiting to receive the blue bottles, amidst the unused pool table and unplugged television, is Stewart Redsky, an alcohol and addictions counsellor. Water is not the only vital stuff hard to come by here, he says. Hope is in short supply, too. "I have to deal with the pain of my people every day," he says. "I have to deal with the frustration of our youth."

It's a frustration the island community has endured now for 100 years. For that long, Shoal Lake 40 First Nation has been completely surrounded by the City of Winnipeg's drinking water supply -- water that no Shoal Lake member can drink from their own taps.

The reasons have to do with how boundaries and responsibilities were decided long ago by the feds, and in more recent decades, threats of water borne infection. The band, which straddles the Ontario-Manitoba border south of the Trans-Canada Highway, has been under a boil-water advisory since 1997.

The people of Shoal Lake 40's thirst for hope is driven by other factors. Substandard housing. A lack of access to jobs off the island. Poor water and sewage treatment. And the fact that crossing the lake during an ice thaw can be deadly.

But lately people here have envisioned, and even begun building, a positive path forward. They call it "Freedom Road."

Tomorrow, Shoal Lake 40 could learn whether the federal government is willing to join in that vision by contributing millions of dollars to the project. Or whether Thursday's scheduled visit by Minister of Natural Resources and Northern Ontario Economic Development Greg Rickford will leave band members where they've been for a century -- isolated, deprived of their surrounding water, and a darkly ironic symbol of how far Canada has yet to travel on its own road towards truth and reconciliation with Indigenous people.

'Pretty damn slow'

Shoal Lake 40's battle against isolation began in 1914, when the City of Winnipeg displaced the First Nation from its historic village site to build a drinking water intake and chlorination plant. With federal blessing, the band was moved onto a roughly 25-square-kilometre peninsula jutting out into the jagged-edged Shoal Lake.

Engineers knew the location wasn't ideal. The nearby Falcon River is full of tannins, difficult-to-remove organic compounds that, when mixed with chlorine, can create cancer-linked trihalomethanes.

So Winnipeg built a dike and canal to separate polluted from potable. In the process, they sliced Shoal Lake 40 in half, effectively creating an island, severing them from their mainland territories, and making residents' water undrinkable. Decades later, an explosion of urban cottages upstream, and their open sewage ponds, would raise the risks further.

Those long ago Winnipeg government decisions about where to build the aqueduct and divert river flow "were all made to preserve water quality," explains the City of Winnipeg's former water manager Tom Pearson, who retired in 2011. On the phone, he told The Tyee that "seen through the lens of the people who were making the decisions," the impact on First Nations were not on the radar a century ago.

An obvious solution would be an on-island water treatment facility, but the feds wouldn't fund it because it's too expensive to build thanks to the lack of road access. Neither could Winnipeg's water simply be siphoned off at the intake because it's treated closer to the city.

The result for Shoal Lake members -- imposed isolation, unequal access to services, and complex and tangled social problems -- is a reality shared by many other First Nations in Canada.

Generations of community leaders, Stewart Redsky laments, have worked to fix their myriad challenges, to little avail.

But things weren't always bleak. Decades ago, the band and its neighbour, Shoal Lake 39 First Nation, were renowned for their economic self-sufficiency. They boasted a thriving commercial fishery, cottage development plans and plentiful bays of wild rice -- harvested by beating the grains with a stick into the bottom of a boat, to be roasted, hulled and sold.

One-by-one, those initiatives were stymied over water and conservation concerns: no cottage developments. No more commercial fishing. Wild rice crops near the reserve dwindled as the lake levels were raised and lowered by authorities. In 1989, Winnipeg and Manitoba offered a $6-million fund in exchange for both Shoal Lake reserves agreeing not to endanger the drinking water with economic initiatives.

As time progressed, Pearson says, the City of Winnipeg's "principle interest" remained "ensuring the water was safe to drink." Hence its concerns about potentially harmful economic First Nations activity. But in the past couple of decades, he said, the city began to seek a more collaborative approach.

"On the other side of the coin, if you happen to be a person living on Shoal Lake 40, it's pretty damn slow," he said.

'No one's going to stop us'

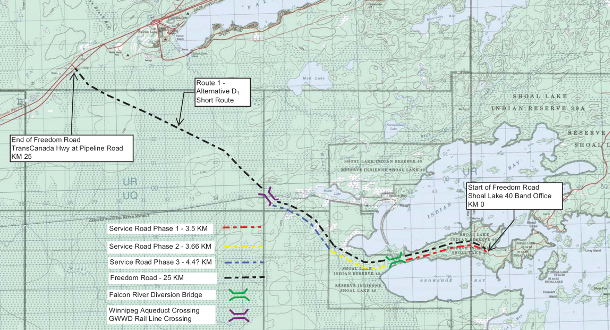

No longer willing to wait, Shoal Lake 40 13 years ago began preparing its own solution. Freedom Road, also called the Western Access Road, would start on the island, bridge the diversion canal to the mainland, and push 28 kilometres west to the Trans-Canada Highway. In so doing, Freedom Road would connect Shoal Lake 40 with jobs and emergency services, and make possible an affordable water treatment plant or storage facility, as well as sewage disposal. The band estimates the total cost of the project to be $25 million.

Tomorrow, when Greg Rickford, the area's MP and a powerful member of cabinet, arrives in Shoal Lake 40, band members will learn whether Stephen Harper's Tory government is willing to chip in a little, a lot, or nothing at all, to building Freedom Road. The governments of Winnipeg and Manitoba have already expressed support.

But the Shoal Lake 40 Nation hasn't waited for governments to make up their minds. Already, they've used scraps of existing funding to get shovels in the ground, putting locals to work and engaging community elders in the process. They've built a temporary steel bridge over the canal that amputated their peninsula from their territories, excavated a gravel quarry on the other side, and are now nearing the end of their designated reserve lands.

Their aim is to keep pushing off-reserve into Manitoba by any means necessary. Realistically, though, the entire project can't be done with the small job-training programs or internal pothole maintenance funding the band has scrounged so far.

Erwin Redsky, Shoal Lake 40's chief since 2002, notes that the initials for the Western Access Road carry a symbolic message. "We called it the W.A.R. because we knew it was going to be a war even just to get support for that road. We kept fighting and fighting for it. We're going to build to the west and no one's going to stop us."

'An incredible story'

Maude Barlow, national chairperson of the Council of Canadians, visited the reserve in April. She's widely known for her campaigning for the right to water, including a stint as senior advisor on water to the UN's General Assembly president.

"I wanted to actually go there and see it for myself," she tells The Tyee. "Here is an incredible story where people who live on the body of water that provides Winnipeg all of its drinking water don't have access to clean water -- they haven't for 18 years.

"The irony cannot be lost on somebody like me who's very involved in getting the UN to recognize the human right to water. We usually think of that in some far-away country but here it is right in our country."

She says she was nervous to cross the melting ice, after hearing about several residents who drowned attempting to cross the lake to reach their reserve.

The solution seemed simple for many years: why not build a bridge across the narrows between the two First Nations? The feds said they'd back it, but around 2002 neighbouring Shoal Lake 39 said no. (That band's chief could not be reached for comment.)

"The Indian Act created those divisions," Chief Redsky said. "Their master plan is to divide us, to make us fight for crumbs. Our communities are being divided rather than the way it was before treaty."

After their neighbours' veto, the chief returned across the water "upset and disappointed" and told his people, "There's no way out but west," he recalls. "Let's build a road to the west. That's when Freedom Road was born."

One of the people who lent his support is Tom Pearson, who admits "More could have been done" over his 28 years working in Winnipeg water management. "I take some responsibility for that."

Building Freedom Road is "not going to solve all the problems" facing the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, he says, "but at least it gives them something that they've accomplished that they can use as a springboard to resolve the other issues they have.

"The folks that need to step up now to make this happen are the feds. The road would be the first step."

The fact that Shoal Lake 40's water had remained undrinkable for nearly two decades suddenly drew new attention in January when, at the other end of the aqueduct, Winnipeg faced a historic two-day boil-water advisory because of suspected E. coli contamination. For the First Nation, it was just a taste of the thousands of days silently spent under similar orders.

In Shoal Lake's Freedom Road initiative, Maude Barlow sees an example of a trend she is encountering in her travels across Canada. Indigenous communities are offering "a great deal of leadership" in transforming the poisoned cup Canada has poured them, she notes.

Still, Stewart Redsky shares the views of many other Shoal Lake 40 members. He won't invest too much hope in Freedom Road's promise until the federal government pays what it takes to make it happen. He says the debt is owed to his people because Ottawa has jurisdiction for Aboriginal peoples but "failed to protect" the band from Winnipeg's push to secure its water.

He's getting tired of pumping up optimism among his family members, who call him a "broken record." They tell him: "'Come on, Grandpa, you're always talking about hope but there's nothing happening. 'You guys are in the paper, the news media -- does that get food in our cupboards? Does that put hope in our troubled youth?'"

Until there's a public announcement to fully fund the proposed road, "then that's when people will begin to hope again," he says.

On the divide

On a windy, sunny day Stewart Redsky brings along the band's treaty consultation co-ordinator Daryl Redsky (the last name of Redsky is ubiquitous in Shoal Lake 40). The two lead a visitor across the diversion dike that separates Winnipeg's water intake from the tannin-infused water that was diverted through the base of Shoal Lake 40's peninsula a century ago. The colour difference between water on either side of the dike is obvious and striking. On one side, the water destined for Winnipeg reflects the rich blue of a clear sky. On the other side of the dike, the water is tinged reddish brown.

Halfway across the stone dam we reach the water intake's no trespassing sign. Returning landward, we cross the temporary steel bridge across the diversion canal installed by the band. This is where Freedom Road begins. Spanning the canal, just two years ago, "was historic," Chief Redsky says. "That was a big breakthrough. We celebrated."

The City of Winnipeg has agreed to fund a permanent replacement bridge here, so the band's next step is to cross the reserve's edge with a year-round roadway, likely along what's used as a winter-only ice road.

The endeavour has brought out young and old alike from the community. One elder, before he died last year, helped clear the path "almost every day," Chief Redsky recalls. The community pressed on and now Redsky estimates the project reaches "halfway to the highway. That's half of Freedom Road, buddy!"

"Whooo!" yells Daryl Redsky defiantly, as a gust of wind rushes westward to where the road vanishes into the Boreal forest.

"Fifty, 60, 70 years down the road, they can say, 'My grandfather built that road you drove down,'" he predicts. "It's a good feeling for me, to imagine these young men -- their great grandchildren -- saying the same thing.

"That's our future."

Original Article

Source: thetyee.ca/

Author: David P. Ball

Waiting to receive the blue bottles, amidst the unused pool table and unplugged television, is Stewart Redsky, an alcohol and addictions counsellor. Water is not the only vital stuff hard to come by here, he says. Hope is in short supply, too. "I have to deal with the pain of my people every day," he says. "I have to deal with the frustration of our youth."

It's a frustration the island community has endured now for 100 years. For that long, Shoal Lake 40 First Nation has been completely surrounded by the City of Winnipeg's drinking water supply -- water that no Shoal Lake member can drink from their own taps.

The reasons have to do with how boundaries and responsibilities were decided long ago by the feds, and in more recent decades, threats of water borne infection. The band, which straddles the Ontario-Manitoba border south of the Trans-Canada Highway, has been under a boil-water advisory since 1997.

The people of Shoal Lake 40's thirst for hope is driven by other factors. Substandard housing. A lack of access to jobs off the island. Poor water and sewage treatment. And the fact that crossing the lake during an ice thaw can be deadly.

But lately people here have envisioned, and even begun building, a positive path forward. They call it "Freedom Road."

Tomorrow, Shoal Lake 40 could learn whether the federal government is willing to join in that vision by contributing millions of dollars to the project. Or whether Thursday's scheduled visit by Minister of Natural Resources and Northern Ontario Economic Development Greg Rickford will leave band members where they've been for a century -- isolated, deprived of their surrounding water, and a darkly ironic symbol of how far Canada has yet to travel on its own road towards truth and reconciliation with Indigenous people.

'Pretty damn slow'

Shoal Lake 40's battle against isolation began in 1914, when the City of Winnipeg displaced the First Nation from its historic village site to build a drinking water intake and chlorination plant. With federal blessing, the band was moved onto a roughly 25-square-kilometre peninsula jutting out into the jagged-edged Shoal Lake.

Engineers knew the location wasn't ideal. The nearby Falcon River is full of tannins, difficult-to-remove organic compounds that, when mixed with chlorine, can create cancer-linked trihalomethanes.

So Winnipeg built a dike and canal to separate polluted from potable. In the process, they sliced Shoal Lake 40 in half, effectively creating an island, severing them from their mainland territories, and making residents' water undrinkable. Decades later, an explosion of urban cottages upstream, and their open sewage ponds, would raise the risks further.

Those long ago Winnipeg government decisions about where to build the aqueduct and divert river flow "were all made to preserve water quality," explains the City of Winnipeg's former water manager Tom Pearson, who retired in 2011. On the phone, he told The Tyee that "seen through the lens of the people who were making the decisions," the impact on First Nations were not on the radar a century ago.

An obvious solution would be an on-island water treatment facility, but the feds wouldn't fund it because it's too expensive to build thanks to the lack of road access. Neither could Winnipeg's water simply be siphoned off at the intake because it's treated closer to the city.

The result for Shoal Lake members -- imposed isolation, unequal access to services, and complex and tangled social problems -- is a reality shared by many other First Nations in Canada.

Generations of community leaders, Stewart Redsky laments, have worked to fix their myriad challenges, to little avail.

But things weren't always bleak. Decades ago, the band and its neighbour, Shoal Lake 39 First Nation, were renowned for their economic self-sufficiency. They boasted a thriving commercial fishery, cottage development plans and plentiful bays of wild rice -- harvested by beating the grains with a stick into the bottom of a boat, to be roasted, hulled and sold.

One-by-one, those initiatives were stymied over water and conservation concerns: no cottage developments. No more commercial fishing. Wild rice crops near the reserve dwindled as the lake levels were raised and lowered by authorities. In 1989, Winnipeg and Manitoba offered a $6-million fund in exchange for both Shoal Lake reserves agreeing not to endanger the drinking water with economic initiatives.

As time progressed, Pearson says, the City of Winnipeg's "principle interest" remained "ensuring the water was safe to drink." Hence its concerns about potentially harmful economic First Nations activity. But in the past couple of decades, he said, the city began to seek a more collaborative approach.

"On the other side of the coin, if you happen to be a person living on Shoal Lake 40, it's pretty damn slow," he said.

'No one's going to stop us'

No longer willing to wait, Shoal Lake 40 13 years ago began preparing its own solution. Freedom Road, also called the Western Access Road, would start on the island, bridge the diversion canal to the mainland, and push 28 kilometres west to the Trans-Canada Highway. In so doing, Freedom Road would connect Shoal Lake 40 with jobs and emergency services, and make possible an affordable water treatment plant or storage facility, as well as sewage disposal. The band estimates the total cost of the project to be $25 million.

Tomorrow, when Greg Rickford, the area's MP and a powerful member of cabinet, arrives in Shoal Lake 40, band members will learn whether Stephen Harper's Tory government is willing to chip in a little, a lot, or nothing at all, to building Freedom Road. The governments of Winnipeg and Manitoba have already expressed support.

But the Shoal Lake 40 Nation hasn't waited for governments to make up their minds. Already, they've used scraps of existing funding to get shovels in the ground, putting locals to work and engaging community elders in the process. They've built a temporary steel bridge over the canal that amputated their peninsula from their territories, excavated a gravel quarry on the other side, and are now nearing the end of their designated reserve lands.

Their aim is to keep pushing off-reserve into Manitoba by any means necessary. Realistically, though, the entire project can't be done with the small job-training programs or internal pothole maintenance funding the band has scrounged so far.

Erwin Redsky, Shoal Lake 40's chief since 2002, notes that the initials for the Western Access Road carry a symbolic message. "We called it the W.A.R. because we knew it was going to be a war even just to get support for that road. We kept fighting and fighting for it. We're going to build to the west and no one's going to stop us."

'An incredible story'

Maude Barlow, national chairperson of the Council of Canadians, visited the reserve in April. She's widely known for her campaigning for the right to water, including a stint as senior advisor on water to the UN's General Assembly president.

"I wanted to actually go there and see it for myself," she tells The Tyee. "Here is an incredible story where people who live on the body of water that provides Winnipeg all of its drinking water don't have access to clean water -- they haven't for 18 years.

"The irony cannot be lost on somebody like me who's very involved in getting the UN to recognize the human right to water. We usually think of that in some far-away country but here it is right in our country."

She says she was nervous to cross the melting ice, after hearing about several residents who drowned attempting to cross the lake to reach their reserve.

The solution seemed simple for many years: why not build a bridge across the narrows between the two First Nations? The feds said they'd back it, but around 2002 neighbouring Shoal Lake 39 said no. (That band's chief could not be reached for comment.)

"The Indian Act created those divisions," Chief Redsky said. "Their master plan is to divide us, to make us fight for crumbs. Our communities are being divided rather than the way it was before treaty."

After their neighbours' veto, the chief returned across the water "upset and disappointed" and told his people, "There's no way out but west," he recalls. "Let's build a road to the west. That's when Freedom Road was born."

One of the people who lent his support is Tom Pearson, who admits "More could have been done" over his 28 years working in Winnipeg water management. "I take some responsibility for that."

Building Freedom Road is "not going to solve all the problems" facing the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, he says, "but at least it gives them something that they've accomplished that they can use as a springboard to resolve the other issues they have.

"The folks that need to step up now to make this happen are the feds. The road would be the first step."

The fact that Shoal Lake 40's water had remained undrinkable for nearly two decades suddenly drew new attention in January when, at the other end of the aqueduct, Winnipeg faced a historic two-day boil-water advisory because of suspected E. coli contamination. For the First Nation, it was just a taste of the thousands of days silently spent under similar orders.

In Shoal Lake's Freedom Road initiative, Maude Barlow sees an example of a trend she is encountering in her travels across Canada. Indigenous communities are offering "a great deal of leadership" in transforming the poisoned cup Canada has poured them, she notes.

Still, Stewart Redsky shares the views of many other Shoal Lake 40 members. He won't invest too much hope in Freedom Road's promise until the federal government pays what it takes to make it happen. He says the debt is owed to his people because Ottawa has jurisdiction for Aboriginal peoples but "failed to protect" the band from Winnipeg's push to secure its water.

He's getting tired of pumping up optimism among his family members, who call him a "broken record." They tell him: "'Come on, Grandpa, you're always talking about hope but there's nothing happening. 'You guys are in the paper, the news media -- does that get food in our cupboards? Does that put hope in our troubled youth?'"

Until there's a public announcement to fully fund the proposed road, "then that's when people will begin to hope again," he says.

On the divide

On a windy, sunny day Stewart Redsky brings along the band's treaty consultation co-ordinator Daryl Redsky (the last name of Redsky is ubiquitous in Shoal Lake 40). The two lead a visitor across the diversion dike that separates Winnipeg's water intake from the tannin-infused water that was diverted through the base of Shoal Lake 40's peninsula a century ago. The colour difference between water on either side of the dike is obvious and striking. On one side, the water destined for Winnipeg reflects the rich blue of a clear sky. On the other side of the dike, the water is tinged reddish brown.

Halfway across the stone dam we reach the water intake's no trespassing sign. Returning landward, we cross the temporary steel bridge across the diversion canal installed by the band. This is where Freedom Road begins. Spanning the canal, just two years ago, "was historic," Chief Redsky says. "That was a big breakthrough. We celebrated."

The City of Winnipeg has agreed to fund a permanent replacement bridge here, so the band's next step is to cross the reserve's edge with a year-round roadway, likely along what's used as a winter-only ice road.

The endeavour has brought out young and old alike from the community. One elder, before he died last year, helped clear the path "almost every day," Chief Redsky recalls. The community pressed on and now Redsky estimates the project reaches "halfway to the highway. That's half of Freedom Road, buddy!"

"Whooo!" yells Daryl Redsky defiantly, as a gust of wind rushes westward to where the road vanishes into the Boreal forest.

"Fifty, 60, 70 years down the road, they can say, 'My grandfather built that road you drove down,'" he predicts. "It's a good feeling for me, to imagine these young men -- their great grandchildren -- saying the same thing.

"That's our future."

Original Article

Source: thetyee.ca/

Author: David P. Ball

No comments:

Post a Comment