Few American voters may yet have heard of Jeremy Corbyn, the previously obscure British parliamentarian who is poised to become leader of the official Labour opposition to David Cameron’s government. But if they have been following the US presidential race, they may already understand the general idea.

Slap a beard on leftwing Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders and make him as casual as a Romantic poet and you have a good approximation of the elderly radical across the Atlantic who is shaking the fragile pillars of the British establishment and could (at least in theory) become Queen Elizabeth’s next prime minister of the not-so United Kingdom.

What is going on here – not among protesters on the street, but in mainstream politics? As with Labour and Corbyn, Sanders is shaking up the Democratic party machine by pulling in vast crowds and tapping youthful enthusiasm in ways that elude opponents in his party, principally the powerful frontrunner, Hillary Clinton.

In Britain, none of the three mainstream candidates to succeed Ed Miliband as Labour leader following his general election defeat in May has Clinton’s record or authority. Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall, all 40-something Labour MPs, look and sound like lacklustre interim leaders, there to watch the store until someone else turns up.

That someone was never meant to be their veteran colleague Jeremy Corbyn, aged 66 and first elected as Labour MP for inner-city Islington in north London in 1983, the same year as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown first reached parliament.

Unlike those two former prime ministers, Corbyn has spent the intervening 32 years as a leftwing rebel, voting against his own government on more than 500 occasions. To qualify for the 2015 leadership ballot among party members he needed the votes of 35 fellow MPs. He got 12, so non-Corbyn supporters kindly gave him the necessary votes to “broaden the debate” – never expecting he would stand any chance of winning. Corbyn himself modestly explained that “it’s my turn” to be the token leftwinger on the hustings platform.

No one is saying that any more. To the amazement of pundits and politicians alike, Corbyn’s campaign took off in July much as Sanders’s own has done for the Democratic nomination. Despite being unfashionable democratic socialists, both men tapped a deep well of resentment against the mainstream political elite by people who feel patronised, neglected and left behind.

Already under assault from rightwing populist insurgencies like the Tea Party and Britain’s anti-European UK Independence Party (Ukip), the elites in the US and UK are reeling. Nor is this phenomenon confined to the narrow realm of these two countries. Seven years into the north Atlantic recessionary trough, with the wider China-centric world increasingly uncertain, the populist revolt is global.

In France, the rightwing National Front, under Marine Le Pen, is again heading towards a presidential run-off against the unpopular François Hollande in 2017. In Italy, the Five Star protest movement is led by a comedian, Bepe Grillo. Most European Union (EU) states, even the moderate Nordic countries, are now experiencing upheavals, usually on the right. They are responding to slow economic growth and rising inequality, and often find their focus in anti-immigrant anger that would delight Donald Trump and much of the US Republican base. Nationalism and xenophobia are on the march again.

In Greece, of course, the anti-establishment populism of the left saw Alexis Tsipras’s Syriza coalition – which includes rightwing nationalists as well as communists – actually win power in January, though it has now split over its compromises in the debt-and-austerity battle it has been waging with Brussels and Berlin. Fresh Greek elections loom. Spain’s equivalent anti-austerity movement, Podemos, also headed by leftwing intellectuals, is pressing hard. Even Angela Merkel of Germany, that placid sheet anchor of European stability, faces grassroots challenges from left and right.

As in the US, where populist insurgency has long enjoyed a more respectable pedigree than among the top-down models of political leadership that linger in Europe, such movements and their leaders usually enjoy their moment in the sun, then fade into internecine acrimony as the elite absorbs their message and recovers. What became of Robert La Follette, Huey Long, of George Wallace, Ross Perot or even Ralph Nader, an advocate of consumer activism as zealous as any Marxist? Come to think of it, where is Sarah Palin today? Or Australia’s Pauline Hanson (though those two won’t quite go away)?

In Britain, racist or economically protectionist parties of the right have traditionally fared little better than the communist party in elections. But what is happening in the UK now has not been seen for decades and has rarely been seen at all since the Chartist agitations of the 1840s.

The country’s ancient parliamentary system with its first-past-the-post voting system, a more solid bulwark against insurgencies than proportional voting methods, acts much like the US’s legislative arrangements in preserving Britain’s long two-party hegemony. The system absorbed the assertive Labour movement before the first world war, and saw off both the fascist appeal of charismatic aristocrat and renegade Oswald Mosley before the second world war and the communist challenge after 1945. It did so more easily than most of its neighbours.

But the resilience which took Britain from global empire a century ago through the Great Depression and two world wars, from decolonization into the EU, looks more brittle today. Paradoxically, it is more vulnerable in the wake of two powerful but divisive premierships, those of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, Britain’s Ronald Reagan and its Bill Clinton in terms of rough equivalence.

Thatcher’s free-market reforms profoundly alienated the old industrial heartlands of Scotland and the North. In Scotland the 1980s arrival of North Sea oil gave economic plausibility to the romantic dreams of separation held by the once marginal Scottish National party (SNP). But it took Blair’s compromises with economic Thatcherism, his role in the Iraq war of 2003, maladroit Brown’s defeat in 2010, and the Cameron coalition’s austerity drive finally to alienate Labour’s core vote in Scotland.

Having already won power in the regional parliament in Edinburgh in 2007, the SNP skilfully blended the elixir of nationalism with left-leaning anti-austerity populism. It did so under the leadership of Alex Salmond and, since Salmond’s 55% to 45% defeat in last year’s independence referendum, Nicola Sturgeon. The pair are among the most adept politicians in Britain.

The consequence of that win has had a profound impact on Labour’s internal struggles. In May’s election campaign, Cameron ruthlessly played on fears in England that Labour’s Miliband might just win power at Westminster without a majority in the House of Commons, and would need to be propped up at a price by Sturgeon’s SNP.

In England, the polls understated Cameron’s strength on 7 May. But their prediction of an SNP landslide in Scotland was correct. The SNP took 56 of the mostly Labour 59 seats there, sealing Cameron’s unexpected majority and Miliband’s doom. Ukip won 4m votes, mostly in England as the unofficial party of Scot-resenting English nationalism, but only one Westminster seat. That’s a winner-take-all voting system for you. The US has it too: most countries nowadays allocate seats by proportional representation (PR) more accurately to reflect votes cast. As Israeli politics repeatedly show, PR has its weaknesses too.

In American terms, Labour’s loss of Scotland was like the Democrats losing New England. It left a party which has never been strong in affluent southern England outside cosmopolitan London short of MPs, dependent on Wales and big cities mostly in its stronghold in the north of England. Even there, Ukip’s assault on EU membership ate into the Labour vote. A barely coded campaign against the surge of economic migrants from the EU’s eastern European flank presented immigration as the harbinger of crime, overcrowded schools and falling wages. It attracted disaffected Labour votes much as Le Pen’s underdog rhetoric does in France.

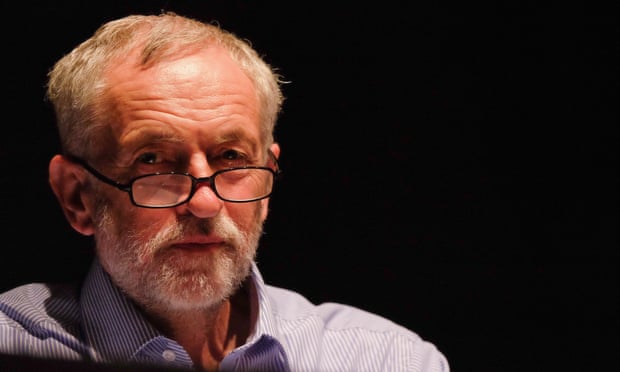

Enter stage left Jeremy Corbyn, a nice man from a comfortable middle class professional background whose parents met campaigning in support of the Republican side in the Spanish civil war of 1936-39. To call him a populist would not do justice to the fiery rhetorical traditions of that breed. He talks gently, dresses casually (sometimes in open-toed sandals and socks) and sports a beard. He is humorous but not witty, non-confrontational and scornful of personal invective in either direction. He has been around since the 1% he condemns so passionately were only a quarter as rich as they are today.

So, like Senator Sanders, Corbyn is a known quantity to those familiar with him – not many until recently. But he is an authentic figure, saying what he has always said about state ownership of utilities like water, power supply and railways (all privatized by Thatcher’s Conservatives), firmly backing Britain’s socialised National Health Service (so much cheaper and fairer than the US model), in favour of higher wages and higher taxes, in favour of controlling the oligarchical excesses of the super-rich.

The equally consistent Sanders (I met him myself when he was still mayor of Burlington, Vermont, in the 80s) would have few grounds for disagreement, though Sanders is vastly more experienced: he has got things done as well as merely talked. The pair might also disagree on foreign policy. Corbyn is anti-Nato, anti-nuclear, and equivocal over EU membership, which Cameron is rashly putting to a referendum in 2017. As an American Jew, Sanders is unlikely to want to share some platforms Corbyn has shared with Islamists and assorted anti-Americans.

Corbyn is a Hugo Chávez man at heart. Few British voters probably go that far. Though many Labour activists would love the journey, they know it doesn’t win elections as did Blair, their triple election winner who is now reviled by much of his own side for crimes both real and imagined. But Corbyn touches a sweet, nostalgic spot and his reception at rallies up and down Britain these past six weeks has been a sensational. Jaded voters who switch off politics on their TV sets filled halls to overflowing: 900 at Nottingham last week to hear Labour’s new Robin Hood, with 300 outside in a street called Maid Marian Way. Soft-spoken Corbyn addressed them all in turn and they cheered him to the echo.

It now looks all but certain that Corbyn will win the Labour leadership when the result is announced on 12 September. Uninspiring rival candidates are too compromised by their record in government or, in Kendall’s case (she may come last), their Blairism. Those who point to the improbability of Corbyn’s high tax-and-spending plans, his threats to banks and bankers, or to Chavez’s legacy and Syriza’s defeats seem to be wasting their time, at least with the constituencies making the choice.

They too represent a lurking problem. Ed Miliband revised the party franchise into what Vermont or Idaho would call an open primary: any self-styled “Labour supporter” can pay £3 ($5) and get the same vote as an MP or activist of 50 years’ standing. Plenty of Conservatives and hard-left activists of the kind Labour has historically excluded have signed up: both groups want a Corbyn win, albeit for opposite reasons. So have disaffected Labour voters who quit in favour of the Greens or SNP over Blair’s wars or his market reforms. So have young people for whom Blair is history (wicked history at that), enchanted by the campaign’s fervour.

Party officials are scrambling to weed out known enemies (Tory MPs with votes are easiest to spot) amid threats of legal action if Corbyn wins. But Labour’s electorate has tripled to 600,000 in weeks and the task is impossible. It also smacks of panic and manipulation. Corbyn may well win handsomely and, if he does not, he will have severely damaged the eventual winner’s candidacy, just as nice Sanders will. That’s politics: we owe George W Bush’s presidency to Nader’s intervention in 2000, just as we do much of Cameron’s win to the SNP’s in May.

Will Corbyn’s career peak in the moment of victory? The mainstream crowd say yes. Polls currently suggest Labour’s share of the vote in 2020 will fall from Miliband’s dismal 30% to 20%, even before Britain’s tabloid press have Googled every last detail of Corbyn’s colourful career. What pleases party activists most often pleases the unaligned electorate rather less in most countries.

But the fired-up “Jez we can” crowd who have packed Corbyn’s meetings disagree. They have cheered remedies which sound like wholesome innocence to many. Bailed-out bankers, the concentration of wealth in obscenely few hands while the tech revolution devours white and blue collar jobs in flaccid economies ... it is not hard to see why people say: “This time it’s different.”

And perhaps it is.

Cameron is trying to keep Scotland in the 307-year-old Union with England while using similar arguments about economic and political sovereignty in his battle to create a halfway house with the EU. The economic recovery is fragile, austerity less severe for most than Cameron’s critics protest, but deeply resented. These are all risky tactics which could destroy Cameron and give Corbyn his chance to try and reshape Britain as we have long known it.

Given that the electorate has rejected Labour radicals like Michael Foot, Neil Kinnock and Ed Miliband well within living memory, it seems unlikely they will embrace the arch-rebel Corbyn who is less experienced and more radical than any of them. The appeal of rightwing nationalism usually trumps red-blooded socialism when the two compete head to head.

But we live in unpredictable times.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Michael White

Slap a beard on leftwing Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders and make him as casual as a Romantic poet and you have a good approximation of the elderly radical across the Atlantic who is shaking the fragile pillars of the British establishment and could (at least in theory) become Queen Elizabeth’s next prime minister of the not-so United Kingdom.

What is going on here – not among protesters on the street, but in mainstream politics? As with Labour and Corbyn, Sanders is shaking up the Democratic party machine by pulling in vast crowds and tapping youthful enthusiasm in ways that elude opponents in his party, principally the powerful frontrunner, Hillary Clinton.

In Britain, none of the three mainstream candidates to succeed Ed Miliband as Labour leader following his general election defeat in May has Clinton’s record or authority. Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall, all 40-something Labour MPs, look and sound like lacklustre interim leaders, there to watch the store until someone else turns up.

That someone was never meant to be their veteran colleague Jeremy Corbyn, aged 66 and first elected as Labour MP for inner-city Islington in north London in 1983, the same year as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown first reached parliament.

Unlike those two former prime ministers, Corbyn has spent the intervening 32 years as a leftwing rebel, voting against his own government on more than 500 occasions. To qualify for the 2015 leadership ballot among party members he needed the votes of 35 fellow MPs. He got 12, so non-Corbyn supporters kindly gave him the necessary votes to “broaden the debate” – never expecting he would stand any chance of winning. Corbyn himself modestly explained that “it’s my turn” to be the token leftwinger on the hustings platform.

No one is saying that any more. To the amazement of pundits and politicians alike, Corbyn’s campaign took off in July much as Sanders’s own has done for the Democratic nomination. Despite being unfashionable democratic socialists, both men tapped a deep well of resentment against the mainstream political elite by people who feel patronised, neglected and left behind.

Already under assault from rightwing populist insurgencies like the Tea Party and Britain’s anti-European UK Independence Party (Ukip), the elites in the US and UK are reeling. Nor is this phenomenon confined to the narrow realm of these two countries. Seven years into the north Atlantic recessionary trough, with the wider China-centric world increasingly uncertain, the populist revolt is global.

In France, the rightwing National Front, under Marine Le Pen, is again heading towards a presidential run-off against the unpopular François Hollande in 2017. In Italy, the Five Star protest movement is led by a comedian, Bepe Grillo. Most European Union (EU) states, even the moderate Nordic countries, are now experiencing upheavals, usually on the right. They are responding to slow economic growth and rising inequality, and often find their focus in anti-immigrant anger that would delight Donald Trump and much of the US Republican base. Nationalism and xenophobia are on the march again.

In Greece, of course, the anti-establishment populism of the left saw Alexis Tsipras’s Syriza coalition – which includes rightwing nationalists as well as communists – actually win power in January, though it has now split over its compromises in the debt-and-austerity battle it has been waging with Brussels and Berlin. Fresh Greek elections loom. Spain’s equivalent anti-austerity movement, Podemos, also headed by leftwing intellectuals, is pressing hard. Even Angela Merkel of Germany, that placid sheet anchor of European stability, faces grassroots challenges from left and right.

As in the US, where populist insurgency has long enjoyed a more respectable pedigree than among the top-down models of political leadership that linger in Europe, such movements and their leaders usually enjoy their moment in the sun, then fade into internecine acrimony as the elite absorbs their message and recovers. What became of Robert La Follette, Huey Long, of George Wallace, Ross Perot or even Ralph Nader, an advocate of consumer activism as zealous as any Marxist? Come to think of it, where is Sarah Palin today? Or Australia’s Pauline Hanson (though those two won’t quite go away)?

In Britain, racist or economically protectionist parties of the right have traditionally fared little better than the communist party in elections. But what is happening in the UK now has not been seen for decades and has rarely been seen at all since the Chartist agitations of the 1840s.

The country’s ancient parliamentary system with its first-past-the-post voting system, a more solid bulwark against insurgencies than proportional voting methods, acts much like the US’s legislative arrangements in preserving Britain’s long two-party hegemony. The system absorbed the assertive Labour movement before the first world war, and saw off both the fascist appeal of charismatic aristocrat and renegade Oswald Mosley before the second world war and the communist challenge after 1945. It did so more easily than most of its neighbours.

But the resilience which took Britain from global empire a century ago through the Great Depression and two world wars, from decolonization into the EU, looks more brittle today. Paradoxically, it is more vulnerable in the wake of two powerful but divisive premierships, those of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, Britain’s Ronald Reagan and its Bill Clinton in terms of rough equivalence.

Thatcher’s free-market reforms profoundly alienated the old industrial heartlands of Scotland and the North. In Scotland the 1980s arrival of North Sea oil gave economic plausibility to the romantic dreams of separation held by the once marginal Scottish National party (SNP). But it took Blair’s compromises with economic Thatcherism, his role in the Iraq war of 2003, maladroit Brown’s defeat in 2010, and the Cameron coalition’s austerity drive finally to alienate Labour’s core vote in Scotland.

Having already won power in the regional parliament in Edinburgh in 2007, the SNP skilfully blended the elixir of nationalism with left-leaning anti-austerity populism. It did so under the leadership of Alex Salmond and, since Salmond’s 55% to 45% defeat in last year’s independence referendum, Nicola Sturgeon. The pair are among the most adept politicians in Britain.

The consequence of that win has had a profound impact on Labour’s internal struggles. In May’s election campaign, Cameron ruthlessly played on fears in England that Labour’s Miliband might just win power at Westminster without a majority in the House of Commons, and would need to be propped up at a price by Sturgeon’s SNP.

In England, the polls understated Cameron’s strength on 7 May. But their prediction of an SNP landslide in Scotland was correct. The SNP took 56 of the mostly Labour 59 seats there, sealing Cameron’s unexpected majority and Miliband’s doom. Ukip won 4m votes, mostly in England as the unofficial party of Scot-resenting English nationalism, but only one Westminster seat. That’s a winner-take-all voting system for you. The US has it too: most countries nowadays allocate seats by proportional representation (PR) more accurately to reflect votes cast. As Israeli politics repeatedly show, PR has its weaknesses too.

In American terms, Labour’s loss of Scotland was like the Democrats losing New England. It left a party which has never been strong in affluent southern England outside cosmopolitan London short of MPs, dependent on Wales and big cities mostly in its stronghold in the north of England. Even there, Ukip’s assault on EU membership ate into the Labour vote. A barely coded campaign against the surge of economic migrants from the EU’s eastern European flank presented immigration as the harbinger of crime, overcrowded schools and falling wages. It attracted disaffected Labour votes much as Le Pen’s underdog rhetoric does in France.

Enter stage left Jeremy Corbyn, a nice man from a comfortable middle class professional background whose parents met campaigning in support of the Republican side in the Spanish civil war of 1936-39. To call him a populist would not do justice to the fiery rhetorical traditions of that breed. He talks gently, dresses casually (sometimes in open-toed sandals and socks) and sports a beard. He is humorous but not witty, non-confrontational and scornful of personal invective in either direction. He has been around since the 1% he condemns so passionately were only a quarter as rich as they are today.

So, like Senator Sanders, Corbyn is a known quantity to those familiar with him – not many until recently. But he is an authentic figure, saying what he has always said about state ownership of utilities like water, power supply and railways (all privatized by Thatcher’s Conservatives), firmly backing Britain’s socialised National Health Service (so much cheaper and fairer than the US model), in favour of higher wages and higher taxes, in favour of controlling the oligarchical excesses of the super-rich.

The equally consistent Sanders (I met him myself when he was still mayor of Burlington, Vermont, in the 80s) would have few grounds for disagreement, though Sanders is vastly more experienced: he has got things done as well as merely talked. The pair might also disagree on foreign policy. Corbyn is anti-Nato, anti-nuclear, and equivocal over EU membership, which Cameron is rashly putting to a referendum in 2017. As an American Jew, Sanders is unlikely to want to share some platforms Corbyn has shared with Islamists and assorted anti-Americans.

Corbyn is a Hugo Chávez man at heart. Few British voters probably go that far. Though many Labour activists would love the journey, they know it doesn’t win elections as did Blair, their triple election winner who is now reviled by much of his own side for crimes both real and imagined. But Corbyn touches a sweet, nostalgic spot and his reception at rallies up and down Britain these past six weeks has been a sensational. Jaded voters who switch off politics on their TV sets filled halls to overflowing: 900 at Nottingham last week to hear Labour’s new Robin Hood, with 300 outside in a street called Maid Marian Way. Soft-spoken Corbyn addressed them all in turn and they cheered him to the echo.

It now looks all but certain that Corbyn will win the Labour leadership when the result is announced on 12 September. Uninspiring rival candidates are too compromised by their record in government or, in Kendall’s case (she may come last), their Blairism. Those who point to the improbability of Corbyn’s high tax-and-spending plans, his threats to banks and bankers, or to Chavez’s legacy and Syriza’s defeats seem to be wasting their time, at least with the constituencies making the choice.

They too represent a lurking problem. Ed Miliband revised the party franchise into what Vermont or Idaho would call an open primary: any self-styled “Labour supporter” can pay £3 ($5) and get the same vote as an MP or activist of 50 years’ standing. Plenty of Conservatives and hard-left activists of the kind Labour has historically excluded have signed up: both groups want a Corbyn win, albeit for opposite reasons. So have disaffected Labour voters who quit in favour of the Greens or SNP over Blair’s wars or his market reforms. So have young people for whom Blair is history (wicked history at that), enchanted by the campaign’s fervour.

Party officials are scrambling to weed out known enemies (Tory MPs with votes are easiest to spot) amid threats of legal action if Corbyn wins. But Labour’s electorate has tripled to 600,000 in weeks and the task is impossible. It also smacks of panic and manipulation. Corbyn may well win handsomely and, if he does not, he will have severely damaged the eventual winner’s candidacy, just as nice Sanders will. That’s politics: we owe George W Bush’s presidency to Nader’s intervention in 2000, just as we do much of Cameron’s win to the SNP’s in May.

Will Corbyn’s career peak in the moment of victory? The mainstream crowd say yes. Polls currently suggest Labour’s share of the vote in 2020 will fall from Miliband’s dismal 30% to 20%, even before Britain’s tabloid press have Googled every last detail of Corbyn’s colourful career. What pleases party activists most often pleases the unaligned electorate rather less in most countries.

But the fired-up “Jez we can” crowd who have packed Corbyn’s meetings disagree. They have cheered remedies which sound like wholesome innocence to many. Bailed-out bankers, the concentration of wealth in obscenely few hands while the tech revolution devours white and blue collar jobs in flaccid economies ... it is not hard to see why people say: “This time it’s different.”

And perhaps it is.

Cameron is trying to keep Scotland in the 307-year-old Union with England while using similar arguments about economic and political sovereignty in his battle to create a halfway house with the EU. The economic recovery is fragile, austerity less severe for most than Cameron’s critics protest, but deeply resented. These are all risky tactics which could destroy Cameron and give Corbyn his chance to try and reshape Britain as we have long known it.

Given that the electorate has rejected Labour radicals like Michael Foot, Neil Kinnock and Ed Miliband well within living memory, it seems unlikely they will embrace the arch-rebel Corbyn who is less experienced and more radical than any of them. The appeal of rightwing nationalism usually trumps red-blooded socialism when the two compete head to head.

But we live in unpredictable times.

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Michael White

No comments:

Post a Comment