What if we had a different electoral system?

The current polls can’t agree on who is first, or second, or third, and the most recent projections show an even closer three-way race than before. This is, however, a result of our electoral system – a system that can occasionally produce unexpected results where a party can win more seats with fewer votes for instance.

Justin Trudeau, who has already promised to try to reform it, favours the alternative vote system. Thomas Mulcair, in the tradition of the NDP, would want to introduceproportional representation. So does Elizabeth May. Stephen Harper is opposed to any reform.

If we had proportional representation, making projections would be incredibly easy. A party receiving 30 per cent of the vote would roughly get 30 per cent of the seats (although it depends on the exact system used).

A system more challenging to project is the alternative vote (also known as a "preferential ballot"). In this system, voters rank the parties or candidates on their ballots. We count the first choices and whoever has more than 50 per cent of the votes is elected. If nobody wins outright, the last-ranked candidate is eliminated and the votes redistributed according to voters’ marked alternative choices. We keep doing that until one candidate crosses the 50 per cent threshold.

Such a system was proposed in Britain four years ago but was defeated in a referendum.

How would such a system affect the outcome of the current election? To answer the question, we used second choices as provided in polls by Ekos and Léger. They show similar results, with New Democrats and Liberals being each other’s second choice by a wide margin. In average, 55 per cent of Liberals have the NDP as second choice and 45 per cent of NDP voters would vote for the Liberals. On the other hand, the Conservatives would primarily choose not to vote in such a way — as many as 55 per cent of Tory voters did not have a second choice.

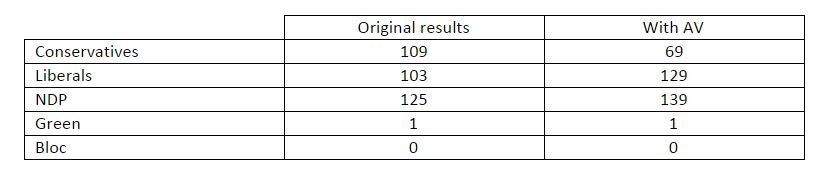

We used these second choices, ran the projections with the current voting intentions and in every riding where no candidate received more than 50 per cent of the vote, we eliminated the lowest ranked candidate and redistributed the votes. We did that until we got a winner by more than 50 per cent in every riding. The results are below.

As you can see, the main effect would be to decrease significantly the seats for the Conservatives. The fact that barely 10 per cent of Liberals or NDP voters have the Tories as second choice is obviously hurting the party in this reckoning. Under a system such as the Alternative Vote, a party wins if it is positioned nicely to receive second choices, which tends to favour parties seen as more in the centre.

The big winner currently would be the Liberals, who would move from third place to fighting for first. We didn’t run the simulations under the alternative vote system, but it’s fair to say both Thomas Mulcair and Justin Trudeau would have a chance of becoming the next prime minister.

The winner was changed in 45 ridings out of 338. Even though very few candidates are currently projected to win with more than 50 per cent of the vote – only 116 to be exact – the new system would actually change the outcome in only about one riding out of six.

It’s important to notice that this is purely a simulation and if the current election were being held under a different system (such as the alternative vote), the dynamics could well be very different. In particular, we are assuming here that people would vote the same way under the AV system. That, however, is a big assumption, and it’s easy to imagine some voters would make a different choice. For instance, people currently trying to vote strategically (i.e: not voting for their first choice because they want their vote to “count”) wouldn’t need to do so. Still, given the information we have, this is pretty much the best we can do.

One thing that has been consistent since the beginning of this campaign is the impossibility of a majority for any party. Switching to the alternative vote would not help with this “problem” in this election. It’s hard to say if the House of Commons under the AV would be more stable than with our current system. You would still essentially need the Liberals and New Democrats to work together.

This article shouldn’t be seen as a support to the alternative vote. This is only an exercise to see what could happen under this very different system. Some provinces (Ontario, B.C.) have tried, unsuccessfully, to change their system. A recent Insight West poll shows that Canadians are seriously divided on this issue. And electoral reform far from being one of the top issues.

With an electorate as divided as ours is now, our current system could well produce a result that doesn’t please the majority of Canadian on Oct. 19. Looking at the results presented here, it’s easy to understand why Trudeau and Mulcair would favour electoral reform while Stephen Harper would rather keep the current system.

We do hope, though, that the party leaders don’t simply pick their favourite electoral system based on which one would give them the best odds.

Bryan Breguet has a B.Sc in economics of politics and a M.Sc in economics from the University of Montreal. He founded TooCloseToCall.ca in 2010 where he provides electoral analysis and projections. He has collaborated with the National Post, Journal de Montreal and l’Actualité.

He will provide analysis and updates for The Huffington Post Canada throughout the federal election campaign. For riding by riding projections, visit his interactive simulator.

Original Article

Source: huffingtonpost.ca/

Author: Bryan Breguet

No comments:

Post a Comment