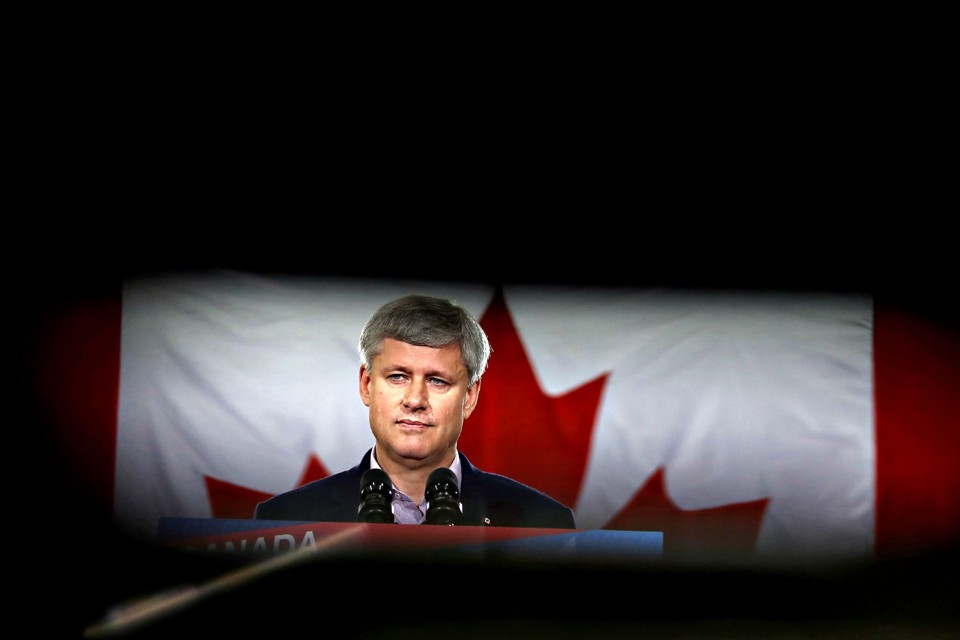

Until recently, Canada’s upcoming election seemed headed for a three-way tie, with potential for constitutional turmoil if Prime Minister Stephen Harper tried to stay in power. Harper’s Conservatives, Opposition Leader Tom Mulcair’s New Democrats, and Justin Trudeau’s Liberals each hovered around 30 percent in the polls ahead of the October 19 vote.

Then the body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed ashore on a Turkish beach, and initial reports suggested relatives had been trying to bring the Syrian boy and his family to Canada, only to be rebuffed under new, Harper-imposed rules that have slowed the admission of Syrian refugees to a trickle. The real story turned out to be more complicated. Canadian immigration officials had actually rejected a refugee application from Alan’s uncle’s family, although Alan’s aunt in Vancouver said the application had been part of a two-stage plan to eventually resettle the entire extended family in Canada.

From his hermetically sealed campaign tour, where Harper permits only a handful of press questions daily, the prime minister reacted to the outcry over Canada’s asylum policies grudgingly, insisting Syrian refugees had to be carefully vetted lest they pose security threats. The real solution, he said, lay in the continued bombing of the Islamic State, a military campaign in which Canada has a minor role. Under aggressive questioning by a CBC reporter, Immigration Minister Chris Alexander refused to say how many Syrians had been admitted to Canada—apparently because the number is so embarrassingly small.

The response seemed stubborn and mean-spirited—a far cry from the days when Canada sent transport planes and squads of immigration officers to speedily admit Vietnamese refugees. A survey released amid the controversy showed the Conservatives slipping into third place in the polls.

The episode only served to underscore the intense animosity Harper inspires among voters who believe he has diminished national attributes they cherish and the rest of the world admires: Canada’s time-honored posture of friendly (and occasionally not-so-friendly) independence from U.S. foreign policy, replaced by feckless, me-too saber-rattling; its once-proud role as lead supplier of UN peacekeepers, already hollowed out under previous Liberal governments, now replaced by frugal financial contributions to support troop deployments by poorer countries; a reputation among its leaders for courtesy and compromise, replaced by a disagreeable, winner-take-all attitude. Previous governments thrashed out major domestic issues at annual conferences featuring the prime minister and provincial premiers, but Harper has refused to attend any. Instead, he has picked unseemly fights with premiers who challenge his policies, once reportedly telling Danny Williams, who was premier of Newfoundland and Labrador at the time, “You’re not going to fuck with my country.”

Harper’s acolytes have taken to mocking the indignation the Canadian leader inspires as Harper Derangement Syndrome: “an ideological hatred of Prime Minister Stephen Harper that is so acute its sufferers’ ability to reason logically is impaired.”

Recently, readers of The Atlantic got a genteel version of this trope when the magazine’s Toronto-reared senior editor, David Frum, posted a rebuttal to a heated New York Times op-ed by the Toronto-based novelist and social commentator Stephen Marche excoriating Harper’s tenure.

Marche’s column hit many highlights of the case against Harper: repeated scandals involving election fraud; a perversely titled “Fair Elections Act” that defanged the independent agency responsible for administering elections and barred it from promoting voting among underrepresented groups; tightened voter-ID rules that target young and aboriginal citizens not prone to voting for the Conservative Party; defunded medical and scientific research; the muzzling of government scientists; a bizarre, almost universally decried debasement of Canada’s census; a prison-building spree that coincides with plummeting crime rates; a preoccupation with promoting dirty Tar Sands oil production to the detriment of the rest of the economy.

Frum, a sometime advisor to the Conservative Party, expresses befuddlement at Marche’s failure to appreciate Harper’s calming grip on the Canadian tiller. Given Harper’s many offenses to the country’s long tradition of political and social liberalism, it’s hard to believe Frum’s mystification is sincere. He zeros in on minor examples of grievances against the prime minister as if they were the totality of the argument, then ridicules them as “micro-transgressions” unworthy of more than mild reproach—certainly not “how Francisco Franco got his start.”

No serious commentator thinks Harper is a nascent Franco, but two aspects of his behavior are especially troubling: his casual disregard for parliamentary norms, and his seemingly willful suppression of information that might conflict with his ideology-driven policies.

The Atlantic’s James Fallows has written about the importance of traditional norms, as opposed to written rules, for the proper functioning of Congress and international diplomacy. Norms are even more important in parliamentary systems, many aspects of which are guided solely by convention. The prime minister is the most powerful actor in the Canadian government, but Canada’s written constitution mentions the position only in passing. Caucus whips enforce party-line voting on almost every vote in Canada’s House of Commons, so prime ministers of majority governments face few obstacles to passing whatever measures they want. Voluntary restraint on the part of the government is the main check on this exceptional power, and a key area where many voters feel Harper has come up short.

When he was in the political opposition, Harper spoke eloquently against the Liberal government’s use of an omnibus bill to cobble unrelated measures involving several government departments into a single package. That bill ran to 21 pages. And yet as prime minister, Harper has made Brobdingnagian bills the default method for implementing his agenda, starting with an 880-page monstrosity in 2010. Two omnibus bills that passed in 2012 ran to a combined 900 pages and amended 135 unrelated laws.

As Harper pointed out before rising to power, omnibus bills “go to only one committee of the House, a committee that will inevitably lack the breadth of expertise required for consideration of a bill of this scope.” They limit debate and force legislators to cast a single up-or-down vote on disparate policies they may support, oppose, or think worthy of amendment.

The Supreme Court of Canada has frequently overturned sections of laws passed in this manner. When the Court found a Harper appointee ineligible for one of its three Quebec seats, Harper and Justice Minister Peter MacKay responded with an unseemly broadside against the chief justice, falsely accusing her of an improper attempt to interfere with the appointment. This drew a sharp rebuke from former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, a Progressive Conservative who now supports the Conservative Party, and demands for an apology from the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists. No apology came.

When a career foreign service officer warned that Canadian troops were turning Afghan prisoners over to the Afghan Army to be tortured, MacKay, then serving as Harper’s defense minister, attacked the officer in the House of Commons as a patsy for the Taliban.

After Parliament’s veterans’ ombudsman criticized the government for replacing injured soldiers’ disability benefits with inadequate lump-sum payments, his appointment was not renewed.

Equally troubling are Harper’s efforts to control and suppress government information, especially that which could run counter to his political agenda. A year after scrapping Canada’s mandatory long-form census, Harper’s government became the first in the history of the British Commonwealth to be found in contempt of Parliament, for failing to provide documentation on several budget items. The independent parliamentary budget officer grew so frustrated with his inability to access the government’s financial records that he sued for them. Like the veterans’ ombudsman, he was not reappointed.

The Prime Minister’s Office and its adjunct, the Privy Council Office, micromanage government activities in the farthest-flung outposts. Responses to the most minor media inquiries are subject to intense vetting that blurs the line between partisan political operations and the traditionally nonpartisan civil service.

Micromanagement has been especially intense during the election campaign. This encompasses not merely, as Frum dismissively describes it, a few rules to make press conferences “less rowdy.” Local Conservative candidates have reportedly been discouraged from taking part in debates or giving interviews. Rigidly enforced media arrangements at Harper campaign stops seem designed not only to keep reporters away from the prime minister, but also to keep them from his carefully vetted supporters and anyone who shows up to protest. This in a country where informal interactions between politicians and the public have long been commonplace. As a former New Democratic staffer now working as a lobbyist wrote in August:

Stephen Harper may become Canada’s first political leader to have conducted an entire national election without once meeting an unvetted, non-partisan ordinary voter; nor encountered a national reporter who had not paid for his seat and the promise of an occasional question. (And only if your question has been vetted and approved and you behave yourself, mind.)

The approach isn’t working. Too many Canadians are embarrassed at having the worst record on climate change in the industrialized world. They recoil at the Harper government’s decision to remove environmental-assessment requirements from the development of most of the country’s waterways. They shake their heads at the corruption trial of a buffoonish Harper-appointed senator (charged with accepting a bribe from Harper’s former top aide, who was inexplicably not charged with proffering the bribe). Even after a lone wannabe jihadist shot a Canadian soldier dead and invaded Parliament to terrorize lawmakers before dying in a shootout, many Canadians object to Harper’s latest anti-terror legislation, which increases domestic surveillance and imposes preventative detention.

Frum has it backwards. The only “difficulty of explaining Harper’s horribleness” involves deciding which of his retrograde policies and postures to leave off an ever-lengthening list of grievances. Somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of the electorate want his government sacked. At the moment, they are evenly divided between two competing center-left parties. In October, voters may choose the one most likely to bring Harper’s nine-year reign to a close, or the Liberals and New Democrats may face pressure to cooperate in forming a new government—a government, let us hope, that is far more respectful of the norms and values that have long made Canada the country that it is.

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com/

Author: Parker Donham

Then the body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed ashore on a Turkish beach, and initial reports suggested relatives had been trying to bring the Syrian boy and his family to Canada, only to be rebuffed under new, Harper-imposed rules that have slowed the admission of Syrian refugees to a trickle. The real story turned out to be more complicated. Canadian immigration officials had actually rejected a refugee application from Alan’s uncle’s family, although Alan’s aunt in Vancouver said the application had been part of a two-stage plan to eventually resettle the entire extended family in Canada.

From his hermetically sealed campaign tour, where Harper permits only a handful of press questions daily, the prime minister reacted to the outcry over Canada’s asylum policies grudgingly, insisting Syrian refugees had to be carefully vetted lest they pose security threats. The real solution, he said, lay in the continued bombing of the Islamic State, a military campaign in which Canada has a minor role. Under aggressive questioning by a CBC reporter, Immigration Minister Chris Alexander refused to say how many Syrians had been admitted to Canada—apparently because the number is so embarrassingly small.

The response seemed stubborn and mean-spirited—a far cry from the days when Canada sent transport planes and squads of immigration officers to speedily admit Vietnamese refugees. A survey released amid the controversy showed the Conservatives slipping into third place in the polls.

The episode only served to underscore the intense animosity Harper inspires among voters who believe he has diminished national attributes they cherish and the rest of the world admires: Canada’s time-honored posture of friendly (and occasionally not-so-friendly) independence from U.S. foreign policy, replaced by feckless, me-too saber-rattling; its once-proud role as lead supplier of UN peacekeepers, already hollowed out under previous Liberal governments, now replaced by frugal financial contributions to support troop deployments by poorer countries; a reputation among its leaders for courtesy and compromise, replaced by a disagreeable, winner-take-all attitude. Previous governments thrashed out major domestic issues at annual conferences featuring the prime minister and provincial premiers, but Harper has refused to attend any. Instead, he has picked unseemly fights with premiers who challenge his policies, once reportedly telling Danny Williams, who was premier of Newfoundland and Labrador at the time, “You’re not going to fuck with my country.”

Harper’s acolytes have taken to mocking the indignation the Canadian leader inspires as Harper Derangement Syndrome: “an ideological hatred of Prime Minister Stephen Harper that is so acute its sufferers’ ability to reason logically is impaired.”

Recently, readers of The Atlantic got a genteel version of this trope when the magazine’s Toronto-reared senior editor, David Frum, posted a rebuttal to a heated New York Times op-ed by the Toronto-based novelist and social commentator Stephen Marche excoriating Harper’s tenure.

Marche’s column hit many highlights of the case against Harper: repeated scandals involving election fraud; a perversely titled “Fair Elections Act” that defanged the independent agency responsible for administering elections and barred it from promoting voting among underrepresented groups; tightened voter-ID rules that target young and aboriginal citizens not prone to voting for the Conservative Party; defunded medical and scientific research; the muzzling of government scientists; a bizarre, almost universally decried debasement of Canada’s census; a prison-building spree that coincides with plummeting crime rates; a preoccupation with promoting dirty Tar Sands oil production to the detriment of the rest of the economy.

Frum, a sometime advisor to the Conservative Party, expresses befuddlement at Marche’s failure to appreciate Harper’s calming grip on the Canadian tiller. Given Harper’s many offenses to the country’s long tradition of political and social liberalism, it’s hard to believe Frum’s mystification is sincere. He zeros in on minor examples of grievances against the prime minister as if they were the totality of the argument, then ridicules them as “micro-transgressions” unworthy of more than mild reproach—certainly not “how Francisco Franco got his start.”

No serious commentator thinks Harper is a nascent Franco, but two aspects of his behavior are especially troubling: his casual disregard for parliamentary norms, and his seemingly willful suppression of information that might conflict with his ideology-driven policies.

The Atlantic’s James Fallows has written about the importance of traditional norms, as opposed to written rules, for the proper functioning of Congress and international diplomacy. Norms are even more important in parliamentary systems, many aspects of which are guided solely by convention. The prime minister is the most powerful actor in the Canadian government, but Canada’s written constitution mentions the position only in passing. Caucus whips enforce party-line voting on almost every vote in Canada’s House of Commons, so prime ministers of majority governments face few obstacles to passing whatever measures they want. Voluntary restraint on the part of the government is the main check on this exceptional power, and a key area where many voters feel Harper has come up short.

When he was in the political opposition, Harper spoke eloquently against the Liberal government’s use of an omnibus bill to cobble unrelated measures involving several government departments into a single package. That bill ran to 21 pages. And yet as prime minister, Harper has made Brobdingnagian bills the default method for implementing his agenda, starting with an 880-page monstrosity in 2010. Two omnibus bills that passed in 2012 ran to a combined 900 pages and amended 135 unrelated laws.

As Harper pointed out before rising to power, omnibus bills “go to only one committee of the House, a committee that will inevitably lack the breadth of expertise required for consideration of a bill of this scope.” They limit debate and force legislators to cast a single up-or-down vote on disparate policies they may support, oppose, or think worthy of amendment.

The Supreme Court of Canada has frequently overturned sections of laws passed in this manner. When the Court found a Harper appointee ineligible for one of its three Quebec seats, Harper and Justice Minister Peter MacKay responded with an unseemly broadside against the chief justice, falsely accusing her of an improper attempt to interfere with the appointment. This drew a sharp rebuke from former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, a Progressive Conservative who now supports the Conservative Party, and demands for an apology from the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists. No apology came.

When a career foreign service officer warned that Canadian troops were turning Afghan prisoners over to the Afghan Army to be tortured, MacKay, then serving as Harper’s defense minister, attacked the officer in the House of Commons as a patsy for the Taliban.

After Parliament’s veterans’ ombudsman criticized the government for replacing injured soldiers’ disability benefits with inadequate lump-sum payments, his appointment was not renewed.

Equally troubling are Harper’s efforts to control and suppress government information, especially that which could run counter to his political agenda. A year after scrapping Canada’s mandatory long-form census, Harper’s government became the first in the history of the British Commonwealth to be found in contempt of Parliament, for failing to provide documentation on several budget items. The independent parliamentary budget officer grew so frustrated with his inability to access the government’s financial records that he sued for them. Like the veterans’ ombudsman, he was not reappointed.

The Prime Minister’s Office and its adjunct, the Privy Council Office, micromanage government activities in the farthest-flung outposts. Responses to the most minor media inquiries are subject to intense vetting that blurs the line between partisan political operations and the traditionally nonpartisan civil service.

Micromanagement has been especially intense during the election campaign. This encompasses not merely, as Frum dismissively describes it, a few rules to make press conferences “less rowdy.” Local Conservative candidates have reportedly been discouraged from taking part in debates or giving interviews. Rigidly enforced media arrangements at Harper campaign stops seem designed not only to keep reporters away from the prime minister, but also to keep them from his carefully vetted supporters and anyone who shows up to protest. This in a country where informal interactions between politicians and the public have long been commonplace. As a former New Democratic staffer now working as a lobbyist wrote in August:

Stephen Harper may become Canada’s first political leader to have conducted an entire national election without once meeting an unvetted, non-partisan ordinary voter; nor encountered a national reporter who had not paid for his seat and the promise of an occasional question. (And only if your question has been vetted and approved and you behave yourself, mind.)

The approach isn’t working. Too many Canadians are embarrassed at having the worst record on climate change in the industrialized world. They recoil at the Harper government’s decision to remove environmental-assessment requirements from the development of most of the country’s waterways. They shake their heads at the corruption trial of a buffoonish Harper-appointed senator (charged with accepting a bribe from Harper’s former top aide, who was inexplicably not charged with proffering the bribe). Even after a lone wannabe jihadist shot a Canadian soldier dead and invaded Parliament to terrorize lawmakers before dying in a shootout, many Canadians object to Harper’s latest anti-terror legislation, which increases domestic surveillance and imposes preventative detention.

Frum has it backwards. The only “difficulty of explaining Harper’s horribleness” involves deciding which of his retrograde policies and postures to leave off an ever-lengthening list of grievances. Somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of the electorate want his government sacked. At the moment, they are evenly divided between two competing center-left parties. In October, voters may choose the one most likely to bring Harper’s nine-year reign to a close, or the Liberals and New Democrats may face pressure to cooperate in forming a new government—a government, let us hope, that is far more respectful of the norms and values that have long made Canada the country that it is.

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com/

Author: Parker Donham

No comments:

Post a Comment