- The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power

- Little, Brown (2015)

Canadians experienced something similar -- and also much that was different. Our 19th century arguably lasted until 1939, giving the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation a chance to build a working-class movement that became the New Democrats. Yet, ironically, the NDP in this election has moved well to the right and may suffer for it.

The America Fraser describes is one that deeply distrusted capitalism even before Karl Marx gave it that name. Thomas Jefferson wanted a republic of small, self-supporting farmers; he distrusted the "moneycrats" who were starting to build an urban industrial economy based on wages.

Jefferson wanted a nation of self-supporting farmers for two reasons: they would be economically independent, and they would strengthen their independence by forming strong local communities where they could resolve local problems as equals.

But the ideal was compromised almost from the start. Railroads pushed west, opening new lands to settlement -- but the settlers were at once dependent on the railroads for access to markets. Railroads needed investors to expand, and investors wanted a good return on their investment. That meant paying workers as little as possible. As economic migrants like the Irish arrived, they found work building those railroads, and toiling at low-paid jobs in the mills and mines.

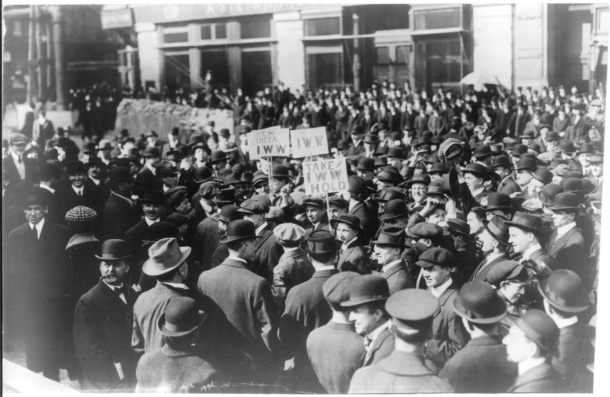

The result was open, violent class war, fought throughout the 19th century and worsening after the American Civil War. With overt slavery abolished, wage slavery became the issue. Still more immigrants poured into the country in search of work; they got it, but on impossible terms.

Another factor influenced the class war: The immigrants had come from long-established rural communities that had at least provided some support against the local landowner. Now they were adrift in a strange land, clinging together in ethnic communities that fought each other even as they resisted their new bosses.

Class war and race war

American class war was also race war, with each new immigrant wave fighting to qualify as "white" and therefore hostile to the doubtfully liberated blacks. A series of booms and busts aggravated the conflict. What Mark Twain called the "Gilded Age" was just that for the top one per cent, but a series of disasters for the other 99 per cent. They had nothing to resist those disasters but violence.

Fraser outlines that violence very well -- a mix of workers' strikes and coercion plus state violence and terror. The economic depressions followed one another so rapidly that most Americans experienced the years 1877 to 1917 as one long misery.

What little we remember of that nightmare is in folk songs and slang: hoboes, bums and tramps were part of a vast proletariat of homeless migrant workers, drifting across the continent to work the next harvest and "bound for movin' on," as Ian Tyson put it much later.

The U.S. and Canada were growing economically, but it was as brutal a method of capital accumulation as Stalin achieved in the 1930s. Immigrants who yearned for a place in their own community got little. Class solidarity was a substitute for community, but rarely extended across ethnic, racial, or gender lines.

The Utopian dream

Americans and Canadians knew that something had gone very wrong. One attempt at a solution was the Utopian community, based on religious or political concepts. Those Utopias flopped, including B.C.'s own Sointula, founded by Finnish workers who wanted their old homeland's sense of community minus its land owners, church, and factory bosses.

After the Civil War, Utopian novels offered new solutions. Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward: 1888-2000 imagined a 19th-century Bostonian revived to find an egalitarian, socialist America, complete with equal wages to all, paid by credit card. It sold a million copies and inspired a "Nationalist Party" to implement its concepts.

To no effect. Under savage capitalism, workers kept striking, and state governments kept sending in troops to shoot them down. The mail bomb, the car bomb and the suicide bomber are little-known additions to the proud list of American inventions.

Immigrants, and workers in general, were portrayed in the print media just as Al-Qaeda and ISIS are in today's digital media: crazy subhumans intent on destroying everything. But many of those immigrants and workers were voters, and patricians like Teddy Roosevelt won power by attacking the "malefactors of great wealth," not the workers.

By the early 20th century, Utopian novels were replaced by dystopias like Jack London's 1908 novel The Iron Heel, which predicted centuries of capitalist oppression ended at last by a dedicated socialist underground. Revolution seemed far more likely than the war that broke out in 1914.

That war saved savage capitalism. Workers sided with their governments, not with their foreign fellow-workers. Governments in turn taxed their rich out of a century's capital accumulation, paid their workers more, and closed an income gap that had been widening for half a century. At war's end Communism began its 70-year run, but the West was prepared to treat its workers better simply as a cost of survival.

By the time of the Great Depression, Fraser argues, the old rhetoric of class warfare had worn out on both sides. The patrician Franklin Roosevelt used government power to build "civilized" capitalism. But the price was high: FDR built the foundations of the military-industrial complex that still rules us 75 years later.

The Canadian divergence

Canada got through the long 19th century of class war with less bloodshed. But the immigrants who settled the Prairies and B.C. fought their own class skirmishes, like the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation grew out of that experience.

In hindsight, the CCF and its successor the New Democrats emerged because Canada had no American-style New Deal, and savage capitalism persisted through the 1930s. But the war seriously weakened it. Tommy Douglas of the CCF took power in Saskatchewan and then brought in Medicare. Working-class politics thrived with the help of strong unions.

The U.S. was set on a different course -- ironically, one foreseen by Jack London in The Iron Heel. After expanding through the 1930s, the great trade unions fell back. As Jack London had warned, the key unions in steel and automobiles made a separate peace with their newly-civilized employers. In return for accepting an age of acquiescence, they got a "private welfare state," with secure incomes that ensured home ownership, health care, and all their kids in college. For the rest of the working class, it has been a long, hard retreat from even the dream of such security.

In effect, the U.S. and Canada have also made a separate peace with all their citizens. Like China after Tiananmen Square, our governments encourage us to pursue our own private gain -- as long as we don't seriously challenge way they run our countries.

Unspeakable, unthinkable

Fraser's key insight appears about halfway through the book, when he examines the impact of the Cold War that smeared all workers with the taint of suspected communism. Even the language of labour was lost. By 1950 you couldn't even discuss events using terms like "class warfare," "plutocracy," "exploitation," or even "socialism." They were not just unspeakable words, they were unthinkable thoughts -- the jargon of the enemy. Labour news vanished from the media, which now focuses on business and the glorification of its CEOs.

So for 75 years, the "free world" has actually been chained into a narrow range of options acceptable to civilized capitalism (now known as neoliberalism). Anything outside those options is out of sight, out of mind, and off the table.

Even the term "working class" is now replaced by the more acceptable "middle class." In its long rightward retreat from the Regina Manifesto, the NDP has come to offer little support for the workers it once spoke for. Tom Mulcair promises to save us -- the middle class -- while balancing the budget. Justin Trudeau raises eyebrows by daring to promise (gasp) deficit spending for just three years -- again, to help the middle class. Some say this puts him on Mulcair's left.

Oddly, this has happened just as politics elsewhere is moving left. Jeremy Corbyn and other left-populists are on the rise in Europe. Socialist Bernie Sanders is a serious contender for the Democrats' presidential nomination. Neoliberal thinking has clearly failed, and people are looking for a language that will let them work toward solutions.

It may be significant that a Liberal like Chrystia Freeland retrieved an old term like "plutocrats" from the memory hole. If the NDP can ever retrieve "working class" as a term of honour, we might be getting somewhere.

Original Article

Source: thetyee.ca/

Author: Crawford Kilian

No comments:

Post a Comment