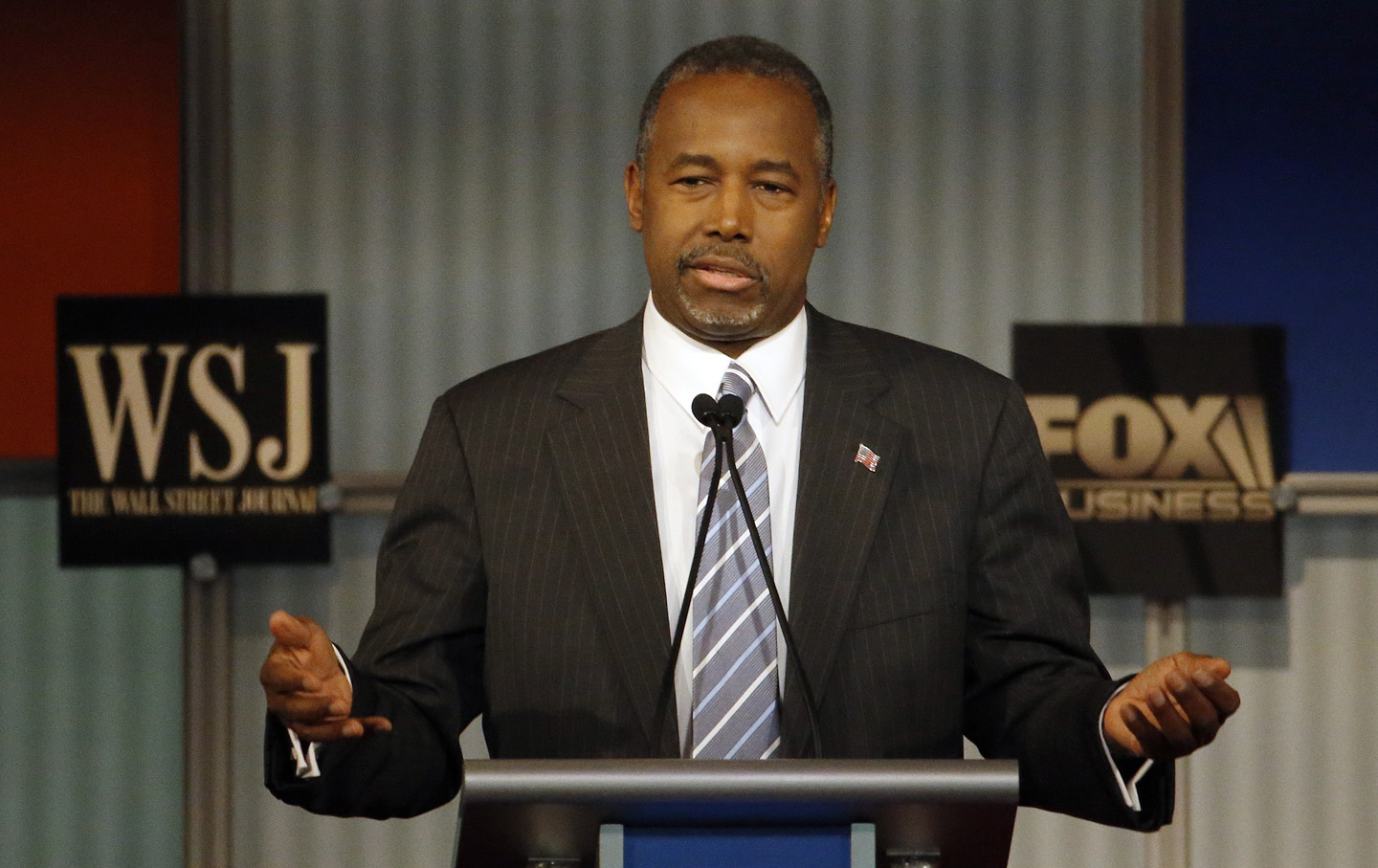

Of course Dr. Ben Carson was wrong when he claimed in the fourth Republican presidential debate that “Every time we raise the minimum wage, the number of jobless people increases.”

The Pulitzer Prize–winning analysts at PolitiFact rated that statement “false”—with no qualifiers or wiggle words like “mostly.”

Minimum-wage hikes are not always associated with immediate spikes in employment; especially in recessionary moments. But PolitiFact notes that “[of the] five minimum wage hikes that occurred when a recovery was under way, joblessness declined four of those times.”

The PolitiFact rebuke was even more stark than the response from Egypt’s antiquities minister to Carson’s claim that the pyramids were built as grain silos—“Does he even deserve a response? He doesn’t.”

So Carson got the economics of minimum-wage increases wrong, as did the other Republican contenders who said “no” to living-wage proposals during Tuesday’s debate. Billionaire Donald Trump was really wrong when he suggested that the problem facing America is “high wages,” and Florida Senator Marco Rubio was really, really wrong when he argued for permanent wage stagnation as a check against job losses to automation.

But if all the Republican front-runners are wrong, it does not necessarily follow that all Democrats are right. There are plenty of cautious Democrats who favor far smaller increases than those proposed by advocates for a living wage.

Doubling the federal minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 an hour, as activists demand, and as Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley propose, may seem like an audacious move to those who are unaware of the history of wage hikes.

But it would not be unprecedented.

History tells us that doubling the minimum wage would not pose the threat to employment imagined by Carson and his partisan compatriots.

President Harry Truman ran for a full term in 1948 on an economic-populist program that called for increasing what was then a 40-cents-an-hour minimum wage. He made it part of an appeal not merely for his own election but for the election of a Democratic Congress—reminding the electorate that the Republican-controlled House and Senate had thwarted his efforts to improve circumstances for working Americans. “I recommended an increase in the minimum wage,” the president told the Democratic National Convention. “What did I get? Nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

The voters got the message. Despite polls that claimed the Republicans would prevail, Truman was easily reelected and Democrats picked up 75 seats in the House—their largest gain since the Franklin Roosevelt landslide of 1932. Democrats also picked up nine US Senate seats. So sweeping was the victory that Democrats took control of both chambers.

Truman recognized a mandate when he saw one. And he moved quickly to implement a “Fair Deal” program that sought to extend on the progress made by FDR’s “New Deal.” One of the 33rd president’s boldest proposals was a major minimum-wage increase; he sought to raise the base wage from 40 cents an hour to 75 cents an hour.

Corporate interests howled, as did Republicans in Congress—and even some conservative Democrats.

But Truman pressed forward, declaring, “It is a measure dictated by social justice. It adds to our economic strength. It is founded on the belief that full human dignity requires at least a minimum level of economic sufficiency and security.”

Congress approved the increase. Truman signed the legislation and on January 24, 1950, he announced: “At midnight tonight the lot of a great many American workers will be substantially improved. Today the minimum wage is 40 cents an hour. Tomorrow the new 75-cent minimum rate goes into effect for the 22 million workers who are protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act, our Federal wage-hour law. Another amendment to that law will provide greatly increased protection for our young boys and girls against dangerous industrial work.”

The president framed the decision to almost double wages in moral and historic terms, explaining, “For many generations we have recognized that there are legitimate roles for the Government to play in protecting our people from economic injustice and hardship. Our Founding Fathers explicitly stated this. In the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, it is declared that this Government was established, among other reasons, to ‘promote the general welfare.’”

But Truman had economics on his side as well.

When the wage hike was implemented, in January 1950, the unemployment rate was 6.5 percent.

One year later, in January 1951, the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent.

Truman counseled at the time of the minimum-wage increase that it would undoubtedly be necessary to raise wages again as part on a long-term strategy for bettering the circumstance of the nation and its people. He urged his successors to recognize that “Our progress in this field points the way for our future action. We shall not relax in our efforts to provide a better life for all our people.”

Dwight Eisenhower listened. He signed a measure that in the spring of 1956 increased the minimum wage from 75 cents an hour to $1 an hour. The unemployment rate was at 4.2 percent when he signed it. A year later, it had fallen to 3.7 percent.

Eisenhower and his allies referred to themselves as “modern Republicans.”

Unfortunately, that is not the term that can be used for Dr. Carson, Donald Trump, Marco Rubio, and the other Republicans who mangle the facts in attempting to make the case against what Franklin Roosevelt taught us was necessary and possible: “the change from starvation wages and starvation employment to living wages and sustained employment.”

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: John Nichols

The Pulitzer Prize–winning analysts at PolitiFact rated that statement “false”—with no qualifiers or wiggle words like “mostly.”

Minimum-wage hikes are not always associated with immediate spikes in employment; especially in recessionary moments. But PolitiFact notes that “[of the] five minimum wage hikes that occurred when a recovery was under way, joblessness declined four of those times.”

The PolitiFact rebuke was even more stark than the response from Egypt’s antiquities minister to Carson’s claim that the pyramids were built as grain silos—“Does he even deserve a response? He doesn’t.”

So Carson got the economics of minimum-wage increases wrong, as did the other Republican contenders who said “no” to living-wage proposals during Tuesday’s debate. Billionaire Donald Trump was really wrong when he suggested that the problem facing America is “high wages,” and Florida Senator Marco Rubio was really, really wrong when he argued for permanent wage stagnation as a check against job losses to automation.

But if all the Republican front-runners are wrong, it does not necessarily follow that all Democrats are right. There are plenty of cautious Democrats who favor far smaller increases than those proposed by advocates for a living wage.

Doubling the federal minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 an hour, as activists demand, and as Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley propose, may seem like an audacious move to those who are unaware of the history of wage hikes.

But it would not be unprecedented.

History tells us that doubling the minimum wage would not pose the threat to employment imagined by Carson and his partisan compatriots.

President Harry Truman ran for a full term in 1948 on an economic-populist program that called for increasing what was then a 40-cents-an-hour minimum wage. He made it part of an appeal not merely for his own election but for the election of a Democratic Congress—reminding the electorate that the Republican-controlled House and Senate had thwarted his efforts to improve circumstances for working Americans. “I recommended an increase in the minimum wage,” the president told the Democratic National Convention. “What did I get? Nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

The voters got the message. Despite polls that claimed the Republicans would prevail, Truman was easily reelected and Democrats picked up 75 seats in the House—their largest gain since the Franklin Roosevelt landslide of 1932. Democrats also picked up nine US Senate seats. So sweeping was the victory that Democrats took control of both chambers.

Truman recognized a mandate when he saw one. And he moved quickly to implement a “Fair Deal” program that sought to extend on the progress made by FDR’s “New Deal.” One of the 33rd president’s boldest proposals was a major minimum-wage increase; he sought to raise the base wage from 40 cents an hour to 75 cents an hour.

Corporate interests howled, as did Republicans in Congress—and even some conservative Democrats.

But Truman pressed forward, declaring, “It is a measure dictated by social justice. It adds to our economic strength. It is founded on the belief that full human dignity requires at least a minimum level of economic sufficiency and security.”

Congress approved the increase. Truman signed the legislation and on January 24, 1950, he announced: “At midnight tonight the lot of a great many American workers will be substantially improved. Today the minimum wage is 40 cents an hour. Tomorrow the new 75-cent minimum rate goes into effect for the 22 million workers who are protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act, our Federal wage-hour law. Another amendment to that law will provide greatly increased protection for our young boys and girls against dangerous industrial work.”

The president framed the decision to almost double wages in moral and historic terms, explaining, “For many generations we have recognized that there are legitimate roles for the Government to play in protecting our people from economic injustice and hardship. Our Founding Fathers explicitly stated this. In the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, it is declared that this Government was established, among other reasons, to ‘promote the general welfare.’”

But Truman had economics on his side as well.

When the wage hike was implemented, in January 1950, the unemployment rate was 6.5 percent.

One year later, in January 1951, the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent.

Truman counseled at the time of the minimum-wage increase that it would undoubtedly be necessary to raise wages again as part on a long-term strategy for bettering the circumstance of the nation and its people. He urged his successors to recognize that “Our progress in this field points the way for our future action. We shall not relax in our efforts to provide a better life for all our people.”

Dwight Eisenhower listened. He signed a measure that in the spring of 1956 increased the minimum wage from 75 cents an hour to $1 an hour. The unemployment rate was at 4.2 percent when he signed it. A year later, it had fallen to 3.7 percent.

Eisenhower and his allies referred to themselves as “modern Republicans.”

Unfortunately, that is not the term that can be used for Dr. Carson, Donald Trump, Marco Rubio, and the other Republicans who mangle the facts in attempting to make the case against what Franklin Roosevelt taught us was necessary and possible: “the change from starvation wages and starvation employment to living wages and sustained employment.”

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: John Nichols

No comments:

Post a Comment