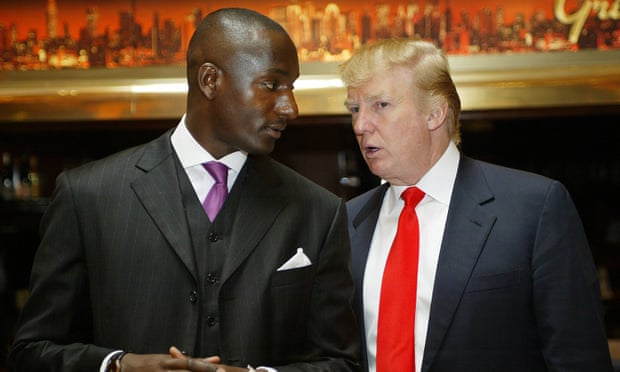

Randal Pinkett’s first day in the Trump Organization was one he would never forget. Summoned to the offices in Trump Tower, the billionaire’s garish midtown skyscraper, Pinkett entered the room as Trump thumbed through a stack of the day’s newspapers and magazines.

It was 2005, and having just won season four of The Apprentice, the only African American to do so in the show’s history, Pinkett expected Trump’s attention. But as the two spoke about his hard-won contract with the company, it was clear Trump really only cared about one thing: himself.

He broke off from the conversation intermittently, pulling a paper from the pile, carefully scanning each page with a yellow Post-It note stuck to it and disregarding the rest – an aide had already combed through the publications to mark out every article that mentioned the boss. This was his morning routine.

“I think that just speaks volumes,” Pinkett said in an interview. “Donald loves Donald.

“His identity is wrapped around being a winner. If you challenge him, or if he’s put into a losing position, now you begin to take Donald out of his comfort zone.”

In interviews with 12 former employees of Donald Trump, the frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination and now one of the most controversial figures in modern American politics, none disagreed with Pinkett’s frank assessment of his former boss’s inflated sense of self.

“I don’t think it’s possible to quantify the size of his ego,” said Barbara Res, a former Trump Organization executive vice-president throughout the 1980s. “It’s too big.”

While Trump’s self-regard is well established, these accounts, some from former staff members who have not spoken about their time in the company since Trump announced his candidacy, give a more detailed insight into the dynamics of Trump’s organisational and management style, which serve perhaps as a portentous insight into how he could operate in the White House.

A consensus emerged of a businessman obsessed with minute detail, prone to micromanagement, who takes little interest in the diversity of his executives or the welfare of lower-level employees. Some said Trump lacks the temperament to deal with setbacks and becomes instantly impatient with those who do not support or agree with him, while remaining resolutely loyal to those who do. Others described their former boss as a workaholic with few true friends, a man sometimes awkward in company outside the workplace.

Provided with a list of detailed claims made by interviewees in this article, Trump told the Guardian in a statement that they were “allegations by disgruntled and disloyal former employees” that were “totally false”.

‘Donald ... did everything’

Trump considered no time of day off limits to call one his closest advisers, Blanche Sprague – who served as a high-powered executive and enforcer until 1990 and described herself as “sort of the meanest one in the company”.

Although ostensibly an executive overseeing construction projects, Sprague, now 67, described her role as often “like a nanny”, dealing with Trump’s direct requests and petty grievances.

“He couldn’t stand to see anything look bad,” Sprague recalled. “He used to call me up at night and say: ‘Did you know that there’s a soda bottle in front of Trump Plaza?’ and I would have to make sure it was picked up right away because he would drive past again to see that it was gone.

“Sometimes it didn’t do much for your ego but at least you got it done.”

On another occasion, following the publication of Trump’s bestselling autobiography and business guide The Art of The Deal in 1987, Sprague recalled accompanying her boss to a book signing in Palm Beach, Florida, where her task was to make sure that he did not run out of his favourite marker pen – which was a particular shade of robin’s egg blue. She stood at his side all evening holding the pens and replenishing his supply.

And yet Sprague remained in awe of her former boss (despite an acrimonious departure which resulted in her suing the company), recalling the times his obsessive attention to detail uncovered the misalignment of terraces during the construction of Trump Tower, or drove the renovation of Central Park’s ice rink in 1981. “Donald, in the end, did everything … No matter how smart you might be, it was Donald,” she said.

Another of Trump’s inner circle from this period, former executive vice president for real estate Louise Sunshine, argued it was this obsession with detail in construction that has driven one of Trump’s most controversial policy positions in 2016: the pledge to build a large wall across the US border with Mexico.

“I think building a wall is something he can really relate to. He’s built so many that I think he can really visualize it. I don’t think he thinks of it as a barrier; I think he thinks of it as some sort of construction,” Sunshine, a registered Democrat, said. She added that “since day one”, Trump’s first lesson to her had been “bad publicity is better than no publicity at all”.

The micromanagement has seemingly continued throughout his life. Justin Goldberg, a former project director who managed the renovation of a property on Wall Street in 1995, recalled how Trump would personally call the painting company to negotiate a deal downwards after it had already been signed, and would point to the smallest details throughout the renovation.

Aaron Sigmond, the former editorial director of the widely lampooned and now defunct Trump Magazine, recalled how Trump would personally select the front cover of every edition of the quarterly publication. Sigmond unabashedly referred to the magazine as “wealth porn” and was keen to point out that the first decision he made when he got the job in 2005 was to run a photo of Trump or a member of his family on every front page.

Trump would also return a magazine mock-up with scribbled suggestions on most pages – no longer in robin’s egg blue, but black sharpie marker.

‘He’s a big-picture guy’

This obsession with detail was accompanied by a relentless work ethic. Most interviewees estimated Trump wakes around 5am, starting his first meetings two hours later, taking sips of caffeinated drinks throughout the day to keep going.

“He somehow requires far less sleep than I do,” said Roger Stone, Trump’s longtime friend and political adviser who spectacularly quit the campaign trail after a public dispute with the candidate in August last year. “Even in the winter time, when he goes to Florida for the weekend, instead of flying back on Monday morning, he flies back on Sunday night so he can be at his desk on Monday morning. And he doesn’t leave on Thursday, he leaves Friday night, after working a full day.”

Louise Sunshine said: “He is a very strategic, methodical person. Nothing goes by him. He could be giving a speech in Ohio and he’ll know what’s going on in the right, what’s going on in the left, what’s going on beyond what’s going on behind.

“He has 360-degree sensory engagement.”

Stone compares him to two previous Republican presidents. “Well, like Reagan, he’s a showman,” he says. “He’s a performer.”

But he rejects the observation that Trump micromanages: “I think that he is someone who will gather the finest minds, he will extract as much information as he can, he will ask hard questions and he’ll make decisions. It’s kind of the Eisenhower model. He doesn’t need to know the name of every sub-sect of Islamic rebels in the African continent.

“He doesn’t need to know all that. He just needs to know the big picture. Like Ronald Reagan, he’s a big picture guy.”

Trump consistently argues that he only hires the best people, and when in office his inner circle will consist of “people you’ve never heard of that are better than all of them”. But one source with intimate knowledge of Trump’s working practice, who declined to be named, disagreed entirely.

“He says he’s going to get the best people around. But he doesn’t do that – he never has,” said the source.

“Because he doesn’t listen to them, and then they leave. And if anybody is ever credited with doing anything good, he gets rid of them because he hates when anybody else gets credit.”

Pinkett, too, was struck by the groupthink of Trump’s inner circle in 2005. “They tend not just to look like him but also think like him,” he said. “So it kind of reinforces his way of thinking.”

Both Res and Pinkett – who have gone on to forge high-powered careers outside of the Trump Organization – said they had not heard from Trump in years following incidents they believed may have been branded acts of disloyalty. (Pinkett called Trump in 2012 to tell him he found his birther campaign against Barack Obama offensive, and Res wrote a book about her time in the organization she believed her former boss did not like; she was cold-shouldered at an event after it was published.)

Res was present in the organization when Trump hit rock bottom. It was the early 1990s, when serious questions were first asked about Trump’s true worth, when an affair with Marla Maples ended his first marriage, and when his investments in Atlantic City casinos nosedived.

“At the exact time it was happening, he blamed it on other people,” Res recalled. He blamed the casino managers, and, according to Res, argued he was “too involved with seeing other women and not paying enough attention”.

“He said that. I’m not making that up,” Res added.

Diversity issues

Pinkett spent a year inside the organization tasked with overseeing a $100m renovation to Trump-branded casinos and hotels in Atlantic City. The job itself ran relatively smoothly, but one thing about the company always struck him: “I don’t think I ever sat in a room with another person of color,” he said.

Sprague, too, struggled to remember the names of any senior minority managers in the company during her tenure.

“We certainly had a wonderful man who ... was Indian,” she said. “We had secretaries who were black, [too].”

Pinkett said he was sometimes called upon to be the public face of Trump’s business when he needed to engage minority communities. In 2006, when the organization attempted (and failed) to build a casino in a majority African American neighbourhood in northern Philadelphia, Pinkett claimed he was asked to canvass for the company in the community, despite his own reservations, and was “threatened” by management when he voiced discontent.

“They said if I didn’t continue my support then there may be ramifications,” Pinkett said.

But Trump’s staunchest supporters point to his record of historically employing women in senior roles.

Roger Stone argued Trump had “far, far more women in positions of responsibility, and generally speaking the women are paid more than men”. Like many of the dozens of former employees who declined requests for interviews with the Guardian, Stone cited a non-disclosure agreement with Trump when pressed on specifics.

Res, who was Trump’s executive vice-president for construction until 1991, acknowledged that he treated men and women equally in the boardroom. But she added: “I’ve come to the conclusion that he probably liked having women around him because he felt better than them in some way or another. Maybe innately he felt better – they were maybe less of a competition.”

Just a ‘regular guy’?

No one, except for Stone, immediately identified Donald Trump as their friend. He never socialised with employees and, according to some, rarely engaged with anyone outside of work, organized functions or family life.

“His socializing was all business,” said Res, who recalled that Trump would meet every Friday evening for dinner with his father Fred Trump, the Brooklyn-based real estate developer who founded the company Donald would inherit. She described the elder Trump as “very, very difficult … loud and boisterous” and someone Trump was eager to impress.

“He loved and respected his father,” said Sprague. “You could be walking on a wire with nothing below you, with him [Donald] holding the other end of the wire. If his father walked into the room, he’d drop it to go say hello.”

Justin Goldberg was project manager on 40 Wall Street, the art deco New York skyscraper bought by Trump in 1995, and was given a job in the Trump Organization through his father, Jay Goldberg, Trump’s long-serving and trusted attorney. He recalled one awkward moment away from work sometime in the mid-nineties.

When Trump had slept over at the family’s residence in upstate New York, Goldberg’s mother prepared breakfast for him in the morning and mistakenly poured salt instead of sugar all over their guest’s cornflakes. Trump, trying to mind his manners, ate the whole salty, soggy breakfast.

“I thought that was pretty impressive,” said Goldberg.

Some former employees argued that despite Trump’s impressive wealth, he remained a “regular guy”.

“He’s a billionaire without being elite,” said Stone, recalling the 1988 Republican convention in New Orleans, where he claimed that he and Trump had decided against a black tie dinner with George H W Bush and chosen instead to seek out the best burgers in town. “See if you can commandeer a limo, and let’s go there instead,” Trump told Stone.

Others dismissed this characterisation as spin. Louise Sunshine recalled Trump’s move away from his father’s empire in Brooklyn and into Manhattan in the mid-70s. The two would drive around the lower end of the city in a limousine, picking out properties they wanted to acquire. Even then, Trump would discuss his dream of purchasing the Mar-a-lago beach resort in Florida. He eventually bought it in 1985, and turned it into a private members’ club with a $100,000 joining fee.

Alma Zamarin, the only current Trump employee to talk to the Guardian, had the most forthright view of this characterisation. The 55-year-old earns $9.75 an hour with no benefits or health insurance, as a part time server in the Trump Hotel in Las Vegas. She has worked there for five years, hoping for a staff contract that has yet to materialise, and struggles to pay bills and feed her retired husband and two children. Her union estimates that Trump pays his hotel workers in Las Vegas, on average, $3.33 less per hour than the average wages on the Las Vegas strip.

“He doesn’t care about me,” Zamarin said. “I think he just cares about his business, how much money he’s making.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Oliver Laughland

It was 2005, and having just won season four of The Apprentice, the only African American to do so in the show’s history, Pinkett expected Trump’s attention. But as the two spoke about his hard-won contract with the company, it was clear Trump really only cared about one thing: himself.

He broke off from the conversation intermittently, pulling a paper from the pile, carefully scanning each page with a yellow Post-It note stuck to it and disregarding the rest – an aide had already combed through the publications to mark out every article that mentioned the boss. This was his morning routine.

“I think that just speaks volumes,” Pinkett said in an interview. “Donald loves Donald.

“His identity is wrapped around being a winner. If you challenge him, or if he’s put into a losing position, now you begin to take Donald out of his comfort zone.”

In interviews with 12 former employees of Donald Trump, the frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination and now one of the most controversial figures in modern American politics, none disagreed with Pinkett’s frank assessment of his former boss’s inflated sense of self.

“I don’t think it’s possible to quantify the size of his ego,” said Barbara Res, a former Trump Organization executive vice-president throughout the 1980s. “It’s too big.”

While Trump’s self-regard is well established, these accounts, some from former staff members who have not spoken about their time in the company since Trump announced his candidacy, give a more detailed insight into the dynamics of Trump’s organisational and management style, which serve perhaps as a portentous insight into how he could operate in the White House.

A consensus emerged of a businessman obsessed with minute detail, prone to micromanagement, who takes little interest in the diversity of his executives or the welfare of lower-level employees. Some said Trump lacks the temperament to deal with setbacks and becomes instantly impatient with those who do not support or agree with him, while remaining resolutely loyal to those who do. Others described their former boss as a workaholic with few true friends, a man sometimes awkward in company outside the workplace.

Provided with a list of detailed claims made by interviewees in this article, Trump told the Guardian in a statement that they were “allegations by disgruntled and disloyal former employees” that were “totally false”.

‘Donald ... did everything’

Trump considered no time of day off limits to call one his closest advisers, Blanche Sprague – who served as a high-powered executive and enforcer until 1990 and described herself as “sort of the meanest one in the company”.

Although ostensibly an executive overseeing construction projects, Sprague, now 67, described her role as often “like a nanny”, dealing with Trump’s direct requests and petty grievances.

“He couldn’t stand to see anything look bad,” Sprague recalled. “He used to call me up at night and say: ‘Did you know that there’s a soda bottle in front of Trump Plaza?’ and I would have to make sure it was picked up right away because he would drive past again to see that it was gone.

“Sometimes it didn’t do much for your ego but at least you got it done.”

On another occasion, following the publication of Trump’s bestselling autobiography and business guide The Art of The Deal in 1987, Sprague recalled accompanying her boss to a book signing in Palm Beach, Florida, where her task was to make sure that he did not run out of his favourite marker pen – which was a particular shade of robin’s egg blue. She stood at his side all evening holding the pens and replenishing his supply.

And yet Sprague remained in awe of her former boss (despite an acrimonious departure which resulted in her suing the company), recalling the times his obsessive attention to detail uncovered the misalignment of terraces during the construction of Trump Tower, or drove the renovation of Central Park’s ice rink in 1981. “Donald, in the end, did everything … No matter how smart you might be, it was Donald,” she said.

Another of Trump’s inner circle from this period, former executive vice president for real estate Louise Sunshine, argued it was this obsession with detail in construction that has driven one of Trump’s most controversial policy positions in 2016: the pledge to build a large wall across the US border with Mexico.

“I think building a wall is something he can really relate to. He’s built so many that I think he can really visualize it. I don’t think he thinks of it as a barrier; I think he thinks of it as some sort of construction,” Sunshine, a registered Democrat, said. She added that “since day one”, Trump’s first lesson to her had been “bad publicity is better than no publicity at all”.

The micromanagement has seemingly continued throughout his life. Justin Goldberg, a former project director who managed the renovation of a property on Wall Street in 1995, recalled how Trump would personally call the painting company to negotiate a deal downwards after it had already been signed, and would point to the smallest details throughout the renovation.

Aaron Sigmond, the former editorial director of the widely lampooned and now defunct Trump Magazine, recalled how Trump would personally select the front cover of every edition of the quarterly publication. Sigmond unabashedly referred to the magazine as “wealth porn” and was keen to point out that the first decision he made when he got the job in 2005 was to run a photo of Trump or a member of his family on every front page.

Trump would also return a magazine mock-up with scribbled suggestions on most pages – no longer in robin’s egg blue, but black sharpie marker.

‘He’s a big-picture guy’

This obsession with detail was accompanied by a relentless work ethic. Most interviewees estimated Trump wakes around 5am, starting his first meetings two hours later, taking sips of caffeinated drinks throughout the day to keep going.

“He somehow requires far less sleep than I do,” said Roger Stone, Trump’s longtime friend and political adviser who spectacularly quit the campaign trail after a public dispute with the candidate in August last year. “Even in the winter time, when he goes to Florida for the weekend, instead of flying back on Monday morning, he flies back on Sunday night so he can be at his desk on Monday morning. And he doesn’t leave on Thursday, he leaves Friday night, after working a full day.”

Louise Sunshine said: “He is a very strategic, methodical person. Nothing goes by him. He could be giving a speech in Ohio and he’ll know what’s going on in the right, what’s going on in the left, what’s going on beyond what’s going on behind.

“He has 360-degree sensory engagement.”

Stone compares him to two previous Republican presidents. “Well, like Reagan, he’s a showman,” he says. “He’s a performer.”

But he rejects the observation that Trump micromanages: “I think that he is someone who will gather the finest minds, he will extract as much information as he can, he will ask hard questions and he’ll make decisions. It’s kind of the Eisenhower model. He doesn’t need to know the name of every sub-sect of Islamic rebels in the African continent.

“He doesn’t need to know all that. He just needs to know the big picture. Like Ronald Reagan, he’s a big picture guy.”

Trump consistently argues that he only hires the best people, and when in office his inner circle will consist of “people you’ve never heard of that are better than all of them”. But one source with intimate knowledge of Trump’s working practice, who declined to be named, disagreed entirely.

“He says he’s going to get the best people around. But he doesn’t do that – he never has,” said the source.

“Because he doesn’t listen to them, and then they leave. And if anybody is ever credited with doing anything good, he gets rid of them because he hates when anybody else gets credit.”

Pinkett, too, was struck by the groupthink of Trump’s inner circle in 2005. “They tend not just to look like him but also think like him,” he said. “So it kind of reinforces his way of thinking.”

Both Res and Pinkett – who have gone on to forge high-powered careers outside of the Trump Organization – said they had not heard from Trump in years following incidents they believed may have been branded acts of disloyalty. (Pinkett called Trump in 2012 to tell him he found his birther campaign against Barack Obama offensive, and Res wrote a book about her time in the organization she believed her former boss did not like; she was cold-shouldered at an event after it was published.)

Res was present in the organization when Trump hit rock bottom. It was the early 1990s, when serious questions were first asked about Trump’s true worth, when an affair with Marla Maples ended his first marriage, and when his investments in Atlantic City casinos nosedived.

“At the exact time it was happening, he blamed it on other people,” Res recalled. He blamed the casino managers, and, according to Res, argued he was “too involved with seeing other women and not paying enough attention”.

“He said that. I’m not making that up,” Res added.

Diversity issues

Pinkett spent a year inside the organization tasked with overseeing a $100m renovation to Trump-branded casinos and hotels in Atlantic City. The job itself ran relatively smoothly, but one thing about the company always struck him: “I don’t think I ever sat in a room with another person of color,” he said.

Sprague, too, struggled to remember the names of any senior minority managers in the company during her tenure.

“We certainly had a wonderful man who ... was Indian,” she said. “We had secretaries who were black, [too].”

Pinkett said he was sometimes called upon to be the public face of Trump’s business when he needed to engage minority communities. In 2006, when the organization attempted (and failed) to build a casino in a majority African American neighbourhood in northern Philadelphia, Pinkett claimed he was asked to canvass for the company in the community, despite his own reservations, and was “threatened” by management when he voiced discontent.

“They said if I didn’t continue my support then there may be ramifications,” Pinkett said.

But Trump’s staunchest supporters point to his record of historically employing women in senior roles.

Roger Stone argued Trump had “far, far more women in positions of responsibility, and generally speaking the women are paid more than men”. Like many of the dozens of former employees who declined requests for interviews with the Guardian, Stone cited a non-disclosure agreement with Trump when pressed on specifics.

Res, who was Trump’s executive vice-president for construction until 1991, acknowledged that he treated men and women equally in the boardroom. But she added: “I’ve come to the conclusion that he probably liked having women around him because he felt better than them in some way or another. Maybe innately he felt better – they were maybe less of a competition.”

Just a ‘regular guy’?

No one, except for Stone, immediately identified Donald Trump as their friend. He never socialised with employees and, according to some, rarely engaged with anyone outside of work, organized functions or family life.

“His socializing was all business,” said Res, who recalled that Trump would meet every Friday evening for dinner with his father Fred Trump, the Brooklyn-based real estate developer who founded the company Donald would inherit. She described the elder Trump as “very, very difficult … loud and boisterous” and someone Trump was eager to impress.

“He loved and respected his father,” said Sprague. “You could be walking on a wire with nothing below you, with him [Donald] holding the other end of the wire. If his father walked into the room, he’d drop it to go say hello.”

Justin Goldberg was project manager on 40 Wall Street, the art deco New York skyscraper bought by Trump in 1995, and was given a job in the Trump Organization through his father, Jay Goldberg, Trump’s long-serving and trusted attorney. He recalled one awkward moment away from work sometime in the mid-nineties.

When Trump had slept over at the family’s residence in upstate New York, Goldberg’s mother prepared breakfast for him in the morning and mistakenly poured salt instead of sugar all over their guest’s cornflakes. Trump, trying to mind his manners, ate the whole salty, soggy breakfast.

“I thought that was pretty impressive,” said Goldberg.

Some former employees argued that despite Trump’s impressive wealth, he remained a “regular guy”.

“He’s a billionaire without being elite,” said Stone, recalling the 1988 Republican convention in New Orleans, where he claimed that he and Trump had decided against a black tie dinner with George H W Bush and chosen instead to seek out the best burgers in town. “See if you can commandeer a limo, and let’s go there instead,” Trump told Stone.

Others dismissed this characterisation as spin. Louise Sunshine recalled Trump’s move away from his father’s empire in Brooklyn and into Manhattan in the mid-70s. The two would drive around the lower end of the city in a limousine, picking out properties they wanted to acquire. Even then, Trump would discuss his dream of purchasing the Mar-a-lago beach resort in Florida. He eventually bought it in 1985, and turned it into a private members’ club with a $100,000 joining fee.

Alma Zamarin, the only current Trump employee to talk to the Guardian, had the most forthright view of this characterisation. The 55-year-old earns $9.75 an hour with no benefits or health insurance, as a part time server in the Trump Hotel in Las Vegas. She has worked there for five years, hoping for a staff contract that has yet to materialise, and struggles to pay bills and feed her retired husband and two children. Her union estimates that Trump pays his hotel workers in Las Vegas, on average, $3.33 less per hour than the average wages on the Las Vegas strip.

“He doesn’t care about me,” Zamarin said. “I think he just cares about his business, how much money he’s making.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com/

Author: Oliver Laughland

No comments:

Post a Comment