A recent Gallup poll found that worries about race relations were at an all-time high in the United States, and it’s easy to see why. This has been a summer of horrific violence born of bias and racism, perpetuating an epidemic of police shootings and mass killings. It has also been a summer of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump baiting crowds at rallies until they scream racial epithets into television cameras, while he promises to usher in a neo-Nixonian era of “law and order” to police people of color in our urban cores.

And yet, against this disheartening backdrop, we believe there is reason to be optimistic about the future of race relations in America.

Below the surface and beyond the viral videos, we see the signs of organizers, activists, researchers, and policy-makers beginning to fundamentally rethink how our rules around race should change. We have seen signs for years, from Occupy to the Movement for Black Lives, that have shown how profoundly and desperately Americans want change. There has been a marked shift away from the unhelpful, race-neutral—or “color-blind”—policy making that has dominated the public debate for the last 35 years, in favor of active efforts to end racial inequity and isolation and invest in people of color. And though it may not be intuitive, we believe that the recent turn against colorblind policy is closely connected to the repudiation of trickle-down economics.

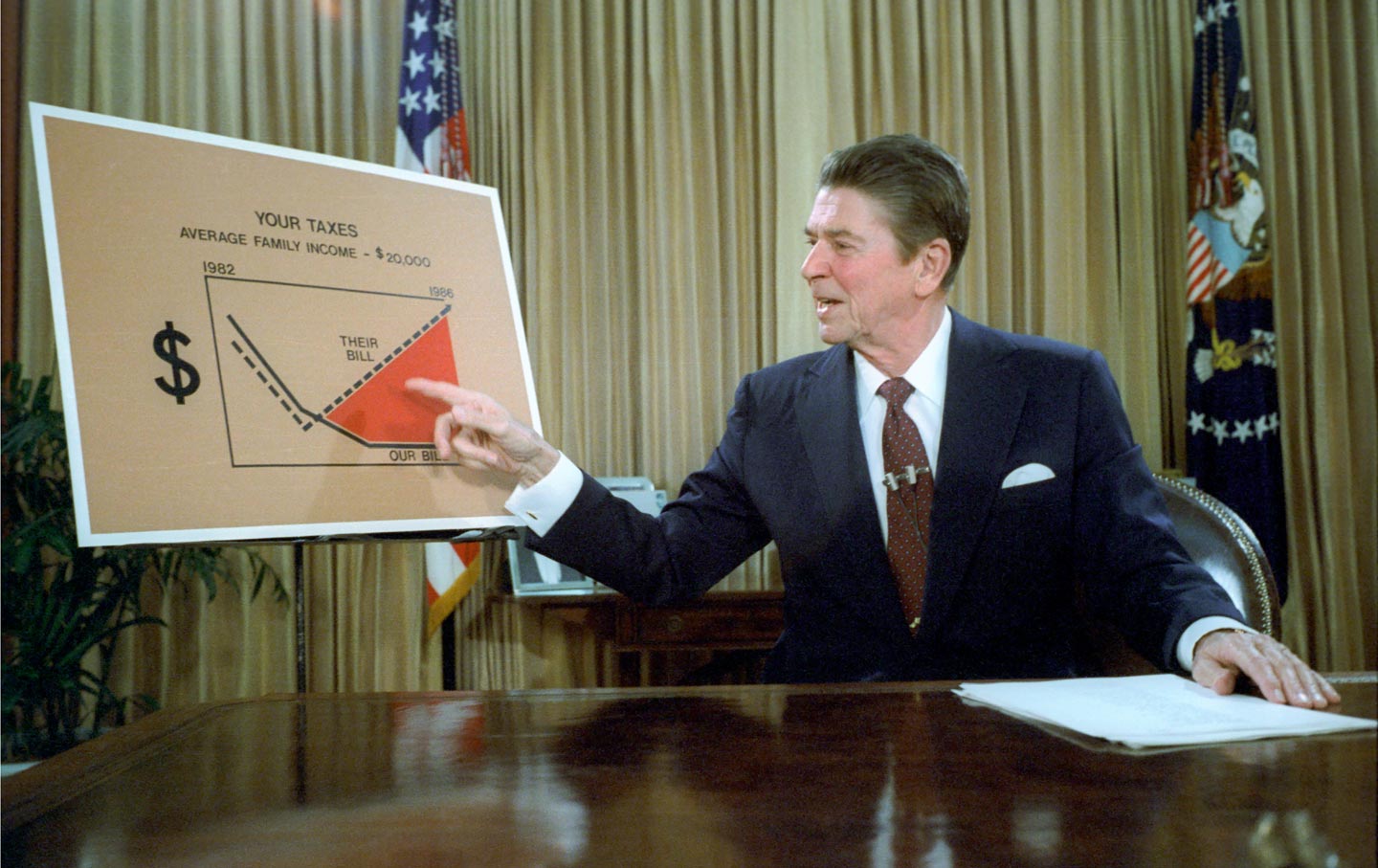

To understand why, it is helpful to examine how the ideologies of trickle-down and color blindness came up together and have reinforced each other.

We are all too familiar with the pitfalls of trickle-down economics, the theory that cutting taxes and regulations at the top will create prosperity for all. As we argue in Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy, more than 30 years of experimentation have shown that imperfect information and institutional distortions reward the powerful, who then write rules to perpetuate this cycle. Thus we end up with an increasing share of limited growth going to the top, with stagnant incomes for most and a hollowing out of the middle class.

But the orthodox belief in trickle-down economics, which has held sway since the 1980s, is no longer dominant in either major party. Donald Trump pays lip service to a kind of anti–trickle down populism, even if in reality he continues to push the Republican line on tax cuts for the rich. On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton has joined figures like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders in calling trickle-down a “failed economic theory.” The emerging progressive economic agenda, which calls for rebalancing power at the top, strengthening our labor market by creating strong floors of standards and greater access for the most vulnerable workers at the bottom, and investing in public goods and economic security through a more robust role for the state, is the antidote to neoliberal tax-cutting.

What’s less widely recognized is that the same market orthodoxy has driven “race-neutral” and “color-blind” policy making. This is the idea that, in order to improve outcomes for people of all races and especially people of color, we must focus on high common standards and accountability and move away from policies that name, discuss, or demarcate people according to racial groupings. But this “trickle-down racial equity” approach does not account for the very unequal life chances and increasingly limited social mobility faced by people of color, which sees black Americans at every level of education earning less than their white peers.

As with trickle-down economics, after more than 30 years of trickle-down racial equity, our schools and neighborhoods and workplaces are no more racially integrated or equal; in fact, the little progress made in the late 1960s and 1970s has stalled and even reversed in some areas.

What both approaches share is a romanticized, and ultimately wrong-headed, view of the way that markets and other institutions work. The human capital approach is based on economic models that assume that market compensation is driven solely by productivity—the effort an individual is willing to exert and the skill with which it is exerted. But we now know this is wrong, and why.

Markets are not perfect and will not “compete away” discrimination or economic inequality. Power and prejudice are embedded, and so we need to use better rules and smart government action to promote market competition rather than enable monopolies. We must view government as jurist, not as bureaucrat. In time, this dawning recognition will ultimately shift not just how we think, but how we act on the intertwined issues of race and economics.

Recognizing the flawed thinking behind both trickle-down and race-neutrality is important. As we have seen in this election season, new thinking opens up the political legitimacy of new policies: stronger financial regulation, investment in jobs and infrastructure in our poorest neighborhoods, changes on the Supreme Court in favor of race-conscious university admissions, and a growing backlash against school segregation. From our own “Rewrite the Racial Rules” report to the Movement for Black Lives policy agenda, we are seeing comprehensive proposals for deep and transformative change. Further, understanding that perfect markets are illusory allows us to see that the unearned profits that accrue to the top actually rob not only people of color but all middle-class and working families of the ability to earn fair wages, decent benefits, and all else that truly equal opportunity would afford them.

Economic prosperity and racial equity for all is more possible now than in the last 30 years. The protests and organizing we’ve already seen are a first step toward acknowledging the problems we have, which is essential to solving them. Now it is time to put the final nails in the coffin of the failed ideologies of trickle-down economics and race-neutral policy. In this election and beyond, we must harness the movement energy in the air and build the political will to advance economic and racial opportunity.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: Felicia Wong and Dorian T. Warren

And yet, against this disheartening backdrop, we believe there is reason to be optimistic about the future of race relations in America.

Below the surface and beyond the viral videos, we see the signs of organizers, activists, researchers, and policy-makers beginning to fundamentally rethink how our rules around race should change. We have seen signs for years, from Occupy to the Movement for Black Lives, that have shown how profoundly and desperately Americans want change. There has been a marked shift away from the unhelpful, race-neutral—or “color-blind”—policy making that has dominated the public debate for the last 35 years, in favor of active efforts to end racial inequity and isolation and invest in people of color. And though it may not be intuitive, we believe that the recent turn against colorblind policy is closely connected to the repudiation of trickle-down economics.

To understand why, it is helpful to examine how the ideologies of trickle-down and color blindness came up together and have reinforced each other.

We are all too familiar with the pitfalls of trickle-down economics, the theory that cutting taxes and regulations at the top will create prosperity for all. As we argue in Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy, more than 30 years of experimentation have shown that imperfect information and institutional distortions reward the powerful, who then write rules to perpetuate this cycle. Thus we end up with an increasing share of limited growth going to the top, with stagnant incomes for most and a hollowing out of the middle class.

But the orthodox belief in trickle-down economics, which has held sway since the 1980s, is no longer dominant in either major party. Donald Trump pays lip service to a kind of anti–trickle down populism, even if in reality he continues to push the Republican line on tax cuts for the rich. On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton has joined figures like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders in calling trickle-down a “failed economic theory.” The emerging progressive economic agenda, which calls for rebalancing power at the top, strengthening our labor market by creating strong floors of standards and greater access for the most vulnerable workers at the bottom, and investing in public goods and economic security through a more robust role for the state, is the antidote to neoliberal tax-cutting.

What’s less widely recognized is that the same market orthodoxy has driven “race-neutral” and “color-blind” policy making. This is the idea that, in order to improve outcomes for people of all races and especially people of color, we must focus on high common standards and accountability and move away from policies that name, discuss, or demarcate people according to racial groupings. But this “trickle-down racial equity” approach does not account for the very unequal life chances and increasingly limited social mobility faced by people of color, which sees black Americans at every level of education earning less than their white peers.

As with trickle-down economics, after more than 30 years of trickle-down racial equity, our schools and neighborhoods and workplaces are no more racially integrated or equal; in fact, the little progress made in the late 1960s and 1970s has stalled and even reversed in some areas.

What both approaches share is a romanticized, and ultimately wrong-headed, view of the way that markets and other institutions work. The human capital approach is based on economic models that assume that market compensation is driven solely by productivity—the effort an individual is willing to exert and the skill with which it is exerted. But we now know this is wrong, and why.

Markets are not perfect and will not “compete away” discrimination or economic inequality. Power and prejudice are embedded, and so we need to use better rules and smart government action to promote market competition rather than enable monopolies. We must view government as jurist, not as bureaucrat. In time, this dawning recognition will ultimately shift not just how we think, but how we act on the intertwined issues of race and economics.

Recognizing the flawed thinking behind both trickle-down and race-neutrality is important. As we have seen in this election season, new thinking opens up the political legitimacy of new policies: stronger financial regulation, investment in jobs and infrastructure in our poorest neighborhoods, changes on the Supreme Court in favor of race-conscious university admissions, and a growing backlash against school segregation. From our own “Rewrite the Racial Rules” report to the Movement for Black Lives policy agenda, we are seeing comprehensive proposals for deep and transformative change. Further, understanding that perfect markets are illusory allows us to see that the unearned profits that accrue to the top actually rob not only people of color but all middle-class and working families of the ability to earn fair wages, decent benefits, and all else that truly equal opportunity would afford them.

Economic prosperity and racial equity for all is more possible now than in the last 30 years. The protests and organizing we’ve already seen are a first step toward acknowledging the problems we have, which is essential to solving them. Now it is time to put the final nails in the coffin of the failed ideologies of trickle-down economics and race-neutral policy. In this election and beyond, we must harness the movement energy in the air and build the political will to advance economic and racial opportunity.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com/

Author: Felicia Wong and Dorian T. Warren

No comments:

Post a Comment