On Sunday, the 89th Academy Awards will honor some of Hollywood’s cinematic achievements of 2016.

When I was younger, my family would gather around our living room to watch the Oscars — especially, when black actors and actresses were nominated. Usually, this meant being disappointed by the results; black narratives and white voters don’t usually go hand-in-hand. That’s because in Hollywood, black films rarely fare well under the white gaze. This year, however, viewers may receive some redemption by way of the number of black films being honored: Moonlight, Hidden Figures, Fences, and I Am Not Your Negro are leading the pack in undeniable ways.

But, with the clear increase in black films and recognition, what if a potential winner, based on a black icon’s life and work, isn’t reflective of the totality of his life? That’s the dilemma I find in I Am Not Your Negro.

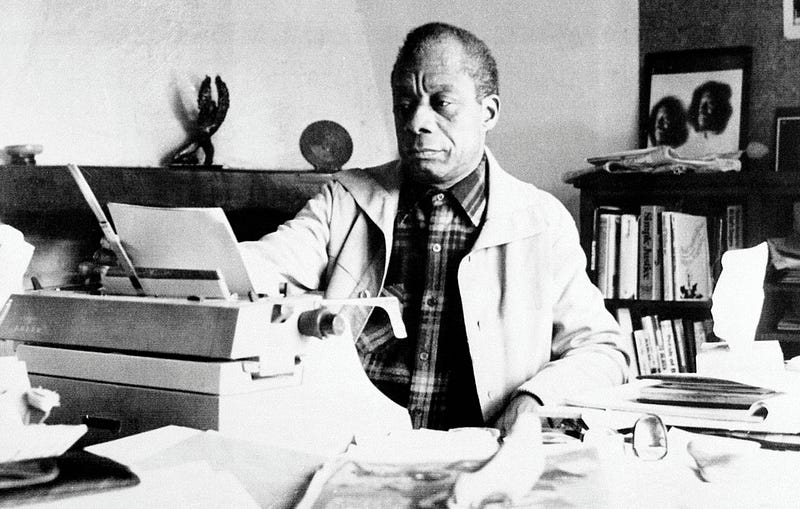

Two weeks ago, in the downtown nation’s capital, I went to the movie theater excited to see Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, the latest documentary about my favorite writer and thought-leader, James Baldwin. I was thrilled to see the direction and the narratives, and to listen to newer concepts that I have yet to be exposed to, even as an avid reader of Baldwin’s works.

I Am Not Your Negro, which has since received critical acclaim and a “Best Documentary” nomination at this year’s Oscars, was released on February 3, the beginning of Black History Month. The film draws its inspiration from Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, a recollection of his friends in the civil rights movement, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. — all three black men killed, in one way or another, by systems of white supremacy and state-sanctioned violence. In the late 1970s, Baldwin told his literary agent that he wanted the lives of these extraordinary men “to bang against and reveal one another as they did in life” in the book. Unfortunately, Baldwin made little progress on the project, only writing down 30 pages of notes before he died from stomach cancer in 1987. Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro was a way of finishing the project.

The documentary, no doubt, had incredible moments in showcasing Baldwin’s vision, often interweaving concepts of white appeasement, black bourgeois sentiments, and past and present racism. The mere mention of the names Aiyana Jones, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Jordan Davis, Freddie Gray, and Sandra Bland still send shivers down my spine.

But I Am Not Your Negro also left me feeling slightly empty and powerless because although it is relevant to our times of state violence, anti-blackness, and respectability politics, it missed a critical component of Baldwin’s life: his sexuality. I Am Not Your Negro also didn’t speak to Baldwin’s changing personal politics post-1968, more centered on blackness instead of centering white audiences and academic elite. Although a film can’t be all things to all viewers, both these missing components were critical parts of Baldwin’s life.

Baldwin was never afraid to broach the subject of sexuality in his work, even over 50 years ago. In Giovanni’s Room (1956), sexuality was a central theme as he writes on the inability to love. A novel on complex representations of homosexuality and bisexuality, Giovanni’s Room was groundbreaking for its time, and was essential to Baldwin’s life and work. He similarly wrote about queer sexuality in his 1949 essay “The Preservation of Innocence” and in his 1979 book Just Above My Head. But I Am Not Your Negro doesn’t engage in the much needed conversation about Baldwin’s sexuality. It similarly glosses over his evolving views on race in America. The film highlighted just how much Baldwin attempted to appeal to white people’s moral compass as a solution to social, political, and economic inequities of the 1950s and 1960s. This struck me as a major problem, especially because he was far less hopeful of what the film shows as racial reconciliation later in his life.

Black art being recognized in a very public way is an incredible feat. After #OscarsSoWhite — created by April Reign in 2016 — called out Hollywood’s whiteness and diversity drought, it’s apparent that the Academy responded to last year’s much-deserved criticism. That’s why it’s heartening to see artists like Baldwin finally receiving some recognition.

But erasing a critical part of Baldwin’s identity and life isn’t helping black queer people, and it isn’t fair to people at these intersections. In the film, the only implication of Baldwin’s sexuality was a transcript released by the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), J. Edgar Hoover, a notorious racist and homophobe, who believed Baldwin to be a “homosexual.” Peck’s documentary thus brings to life Baldwin’s views on race and racism in America, while simultaneously leaving out how critical intersectionality is when sexuality is part of a human’s lived experience.

This isn’t the first time black queer people were erased — and it probably won’t be the last. As a black queer man, I’m always disturbed at how quickly we forget details of a black person’s life merely because of sexual identity. Baldwin, like others, understood just how disadvantaged he was when his queerness intersected with his blackness. Instead of hiding from it — and realizing that vitriol would come from black and white people for two distinct reasons — he fought head-on, writing it in his books and speaking about it publicly.

Baldwin’s sexualitiy was complex, but he used it as an interpretation of his own life experiences. When Baldwin spoke about dehumanization, it wasn’t only as a black man or a queer man, but as a black and queer man who would be criminalized for both. This film will hopefully spark interest in people to learn more about Baldwin, but it could have done so with more nuance and compassion for his lived experiences.

Compare I Am Not Your Negro with Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, which received several Oscar nominations, including “Best Picture.” A coming-of-age story featuring the three iterations — a child, a teenager, and an adult — of its main character, Chiron, Moonlight challenges the audience’s understanding of masculinity, sexualities, poverty, abuse, and drug addiction. It was done with compassion, nuance, silence, and a moment-in-time that was new for many of us.

It’s certainly honorable that Peck dedicated time and resources to expanding on Baldwin’s work. I Am Not Your Negro does introduce viewers to one of the best literary geniuses of the past two centuries. Nonetheless, I Am Not Your Negro failing to discuss, or bring to light, Baldwin’s sexuality is par for the course when revisiting the life of black creatives.

It is now time to understand that black people are not the mere sum of our parts — and films and media must capture our lived experiences more accurately.

Original Article

Source: thinkprogress.org/

Author: Preston Mitchum

When I was younger, my family would gather around our living room to watch the Oscars — especially, when black actors and actresses were nominated. Usually, this meant being disappointed by the results; black narratives and white voters don’t usually go hand-in-hand. That’s because in Hollywood, black films rarely fare well under the white gaze. This year, however, viewers may receive some redemption by way of the number of black films being honored: Moonlight, Hidden Figures, Fences, and I Am Not Your Negro are leading the pack in undeniable ways.

But, with the clear increase in black films and recognition, what if a potential winner, based on a black icon’s life and work, isn’t reflective of the totality of his life? That’s the dilemma I find in I Am Not Your Negro.

Two weeks ago, in the downtown nation’s capital, I went to the movie theater excited to see Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, the latest documentary about my favorite writer and thought-leader, James Baldwin. I was thrilled to see the direction and the narratives, and to listen to newer concepts that I have yet to be exposed to, even as an avid reader of Baldwin’s works.

I Am Not Your Negro, which has since received critical acclaim and a “Best Documentary” nomination at this year’s Oscars, was released on February 3, the beginning of Black History Month. The film draws its inspiration from Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, a recollection of his friends in the civil rights movement, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. — all three black men killed, in one way or another, by systems of white supremacy and state-sanctioned violence. In the late 1970s, Baldwin told his literary agent that he wanted the lives of these extraordinary men “to bang against and reveal one another as they did in life” in the book. Unfortunately, Baldwin made little progress on the project, only writing down 30 pages of notes before he died from stomach cancer in 1987. Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro was a way of finishing the project.

The documentary, no doubt, had incredible moments in showcasing Baldwin’s vision, often interweaving concepts of white appeasement, black bourgeois sentiments, and past and present racism. The mere mention of the names Aiyana Jones, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Jordan Davis, Freddie Gray, and Sandra Bland still send shivers down my spine.

But I Am Not Your Negro also left me feeling slightly empty and powerless because although it is relevant to our times of state violence, anti-blackness, and respectability politics, it missed a critical component of Baldwin’s life: his sexuality. I Am Not Your Negro also didn’t speak to Baldwin’s changing personal politics post-1968, more centered on blackness instead of centering white audiences and academic elite. Although a film can’t be all things to all viewers, both these missing components were critical parts of Baldwin’s life.

Baldwin was never afraid to broach the subject of sexuality in his work, even over 50 years ago. In Giovanni’s Room (1956), sexuality was a central theme as he writes on the inability to love. A novel on complex representations of homosexuality and bisexuality, Giovanni’s Room was groundbreaking for its time, and was essential to Baldwin’s life and work. He similarly wrote about queer sexuality in his 1949 essay “The Preservation of Innocence” and in his 1979 book Just Above My Head. But I Am Not Your Negro doesn’t engage in the much needed conversation about Baldwin’s sexuality. It similarly glosses over his evolving views on race in America. The film highlighted just how much Baldwin attempted to appeal to white people’s moral compass as a solution to social, political, and economic inequities of the 1950s and 1960s. This struck me as a major problem, especially because he was far less hopeful of what the film shows as racial reconciliation later in his life.

Black art being recognized in a very public way is an incredible feat. After #OscarsSoWhite — created by April Reign in 2016 — called out Hollywood’s whiteness and diversity drought, it’s apparent that the Academy responded to last year’s much-deserved criticism. That’s why it’s heartening to see artists like Baldwin finally receiving some recognition.

But erasing a critical part of Baldwin’s identity and life isn’t helping black queer people, and it isn’t fair to people at these intersections. In the film, the only implication of Baldwin’s sexuality was a transcript released by the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), J. Edgar Hoover, a notorious racist and homophobe, who believed Baldwin to be a “homosexual.” Peck’s documentary thus brings to life Baldwin’s views on race and racism in America, while simultaneously leaving out how critical intersectionality is when sexuality is part of a human’s lived experience.

This isn’t the first time black queer people were erased — and it probably won’t be the last. As a black queer man, I’m always disturbed at how quickly we forget details of a black person’s life merely because of sexual identity. Baldwin, like others, understood just how disadvantaged he was when his queerness intersected with his blackness. Instead of hiding from it — and realizing that vitriol would come from black and white people for two distinct reasons — he fought head-on, writing it in his books and speaking about it publicly.

Baldwin’s sexualitiy was complex, but he used it as an interpretation of his own life experiences. When Baldwin spoke about dehumanization, it wasn’t only as a black man or a queer man, but as a black and queer man who would be criminalized for both. This film will hopefully spark interest in people to learn more about Baldwin, but it could have done so with more nuance and compassion for his lived experiences.

Compare I Am Not Your Negro with Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, which received several Oscar nominations, including “Best Picture.” A coming-of-age story featuring the three iterations — a child, a teenager, and an adult — of its main character, Chiron, Moonlight challenges the audience’s understanding of masculinity, sexualities, poverty, abuse, and drug addiction. It was done with compassion, nuance, silence, and a moment-in-time that was new for many of us.

It’s certainly honorable that Peck dedicated time and resources to expanding on Baldwin’s work. I Am Not Your Negro does introduce viewers to one of the best literary geniuses of the past two centuries. Nonetheless, I Am Not Your Negro failing to discuss, or bring to light, Baldwin’s sexuality is par for the course when revisiting the life of black creatives.

It is now time to understand that black people are not the mere sum of our parts — and films and media must capture our lived experiences more accurately.

Original Article

Source: thinkprogress.org/

Author: Preston Mitchum

No comments:

Post a Comment