We recently marked the seventh anniversary of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, President Obama’s response to the 2008 financial crisis. President Trump and the Republicans are hard at work trying to undermine it, but there is one interesting element they’re having trouble weakening: credit-card reform. It’s a small part of the act, but an important one to understand, because it can serve as a model for fixing some of the more abusive parts of our economy.

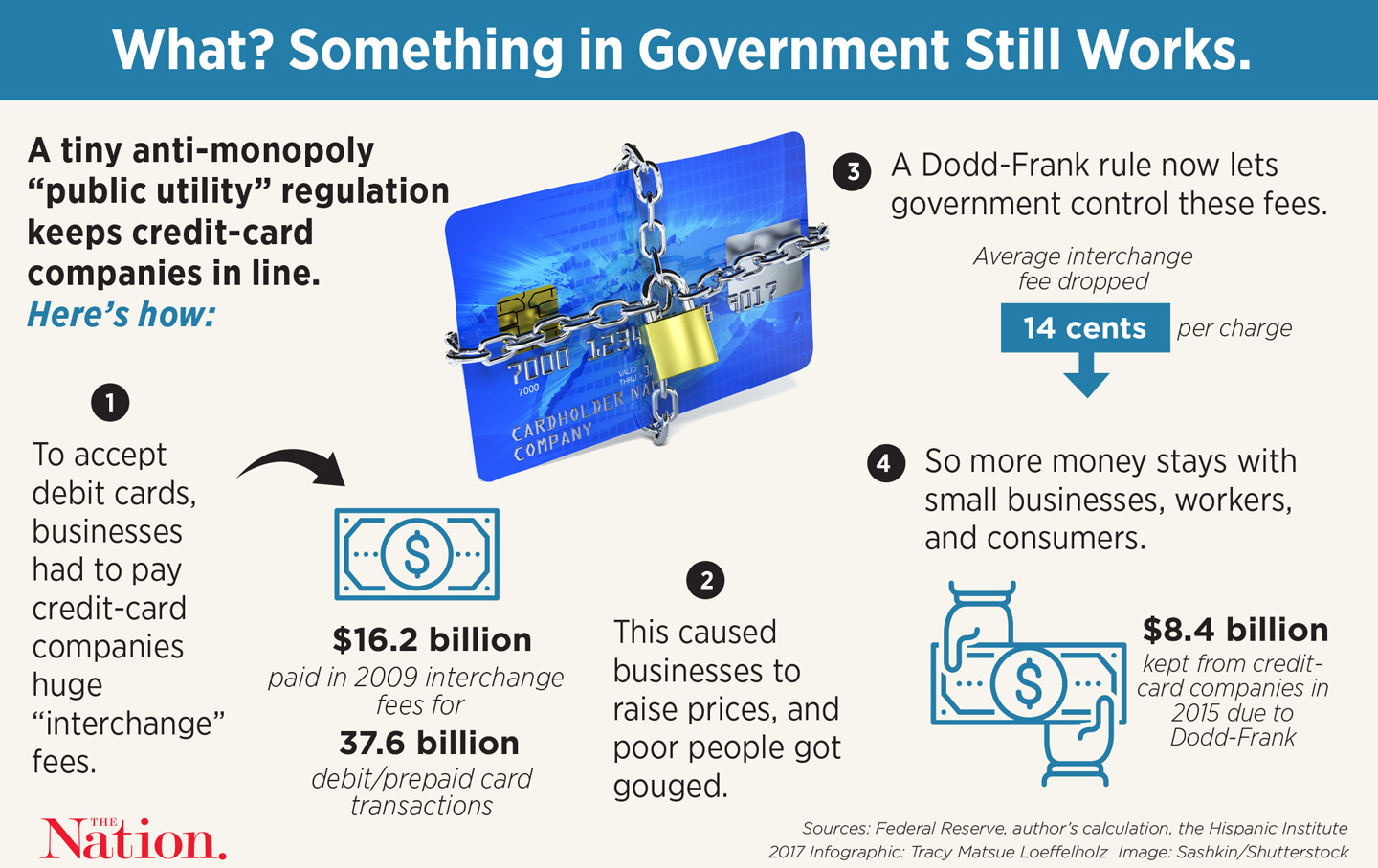

When businesses choose to accept credit and debit cards, they must pay an “interchange fee” to the credit-card companies. This is a big cost for them. For a long time, credit-card companies, which are near monopolies, forced businesses to accept their terms: high rates, no minimums allowed, no discounts for people paying in cash, and more. This particularly affected poor people because they pay in cash and had to shell out more to cover the higher prices caused by card use.

Dodd-Frank changed all this. It said that interchange fees must be “reasonable and proportional” to the costs incurred for the cards. (The Fed interpreted this to mean that the fee must be, at maximum, “21 cents plus 0.05 percent multiplied by the value of the transaction, plus a 1-cent fraud-prevention adjustment, if eligible.”) It also opened up the network for competition and allowed merchants and businesses to set minimums and offer discounts for using cash. In other words, the government intervened directly and told monopolistic credit-card companies what rates they could set and what rules they would play by.

How simple and straightforward is that? This immediately solved several problems at once. It moved power from the too-powerful financial sector to the real economy of sellers and buyers. Local small businesses now have more control over the terms under which they’ll accept payments, rather than having those terms forced on them by faraway credit conglomerates. And it also simplifies regulatory enforcement.

This same spirit lies behind net neutrality, another important legacy of the Obama era that is now under attack. Net neutrality is the simple idea that Internet service providers should treat all of the traffic passing over their networks equally. As with Dodd-Frank, it allows the government to set a rate: All digital traffic must be allowed to travel over Internet infrastructure for the same cost. It doesn’t allow the market to set rates, and this benefits the whole economy.

This type of regulation—setting fair rates and opening up closed networks to competition, taking these decisions out of the private market—is traditionally known as “public utility” regulation. For years, policy-makers have naively assumed that market competition would break up significant concentrations of economic power. But as the economy has become more concentrated and monopolies have grown, market competition has proved a weak mechanism for protecting the public interest.

The legal historian William Novak notes that the notion of public utility was essential to the nation’s first wave of reforms, from the Gilded Age to the New Deal. An 1877 Supreme Court case, Munn v. Illinois, determined that the government could regulate businesses “affected with a public interest,” including the railroads, telephone and telegraph companies, utilities, and banking. Years later, during the New Deal, Justice Felix Frankfurter noted that the existence of a public interest “made possible, within a selected field, a degree of experimentation in governmental direction of economic activity of vast import and beyond any historical parallel.”

Liberals need to embrace these arguments in the 21st century, especially as Democrats look to tackle concentration and corporate power, and encourage the government to directly intervene to set rates in areas of public interest. “All-payer rate setting,” for example, would mean that everyone pays the same price for the same services in health care. Looking at the increasing centrality of major tech companies in our day-to-day lives, we will need the government to instruct them not to discriminate and to protect their customers’ data. These will be difficult fights, but we already have a proud history of regulation that need only be brought into a new era.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com

Author: Mike Konczal

When businesses choose to accept credit and debit cards, they must pay an “interchange fee” to the credit-card companies. This is a big cost for them. For a long time, credit-card companies, which are near monopolies, forced businesses to accept their terms: high rates, no minimums allowed, no discounts for people paying in cash, and more. This particularly affected poor people because they pay in cash and had to shell out more to cover the higher prices caused by card use.

Dodd-Frank changed all this. It said that interchange fees must be “reasonable and proportional” to the costs incurred for the cards. (The Fed interpreted this to mean that the fee must be, at maximum, “21 cents plus 0.05 percent multiplied by the value of the transaction, plus a 1-cent fraud-prevention adjustment, if eligible.”) It also opened up the network for competition and allowed merchants and businesses to set minimums and offer discounts for using cash. In other words, the government intervened directly and told monopolistic credit-card companies what rates they could set and what rules they would play by.

How simple and straightforward is that? This immediately solved several problems at once. It moved power from the too-powerful financial sector to the real economy of sellers and buyers. Local small businesses now have more control over the terms under which they’ll accept payments, rather than having those terms forced on them by faraway credit conglomerates. And it also simplifies regulatory enforcement.

This same spirit lies behind net neutrality, another important legacy of the Obama era that is now under attack. Net neutrality is the simple idea that Internet service providers should treat all of the traffic passing over their networks equally. As with Dodd-Frank, it allows the government to set a rate: All digital traffic must be allowed to travel over Internet infrastructure for the same cost. It doesn’t allow the market to set rates, and this benefits the whole economy.

This type of regulation—setting fair rates and opening up closed networks to competition, taking these decisions out of the private market—is traditionally known as “public utility” regulation. For years, policy-makers have naively assumed that market competition would break up significant concentrations of economic power. But as the economy has become more concentrated and monopolies have grown, market competition has proved a weak mechanism for protecting the public interest.

The legal historian William Novak notes that the notion of public utility was essential to the nation’s first wave of reforms, from the Gilded Age to the New Deal. An 1877 Supreme Court case, Munn v. Illinois, determined that the government could regulate businesses “affected with a public interest,” including the railroads, telephone and telegraph companies, utilities, and banking. Years later, during the New Deal, Justice Felix Frankfurter noted that the existence of a public interest “made possible, within a selected field, a degree of experimentation in governmental direction of economic activity of vast import and beyond any historical parallel.”

Liberals need to embrace these arguments in the 21st century, especially as Democrats look to tackle concentration and corporate power, and encourage the government to directly intervene to set rates in areas of public interest. “All-payer rate setting,” for example, would mean that everyone pays the same price for the same services in health care. Looking at the increasing centrality of major tech companies in our day-to-day lives, we will need the government to instruct them not to discriminate and to protect their customers’ data. These will be difficult fights, but we already have a proud history of regulation that need only be brought into a new era.

Original Article

Source: thenation.com

Author: Mike Konczal

No comments:

Post a Comment