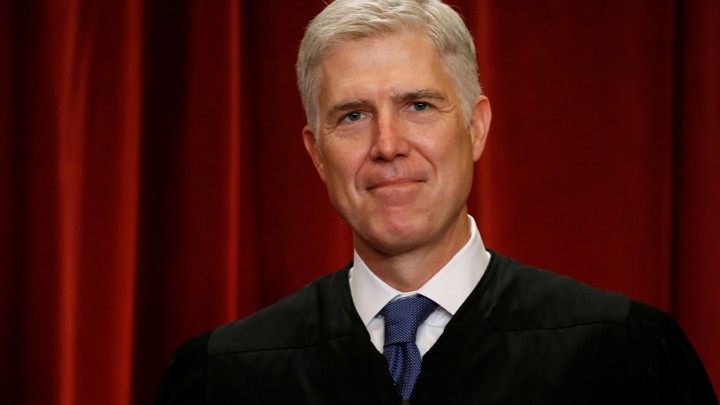

“There’s no such thing as a Republican judge or a Democratic judge,” Neil Gorsuch told the nation during his confirmation hearings. “We just have judges in this country.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters in July that he doesn’t quite agree. Asked to explain to his party’s base the Senate’s lack of legislative accomplishment, McConnell said, “Well, we have a new Supreme Court justice.”

Gorsuch hasn’t commented on that statement. But he was quite happy to appear with McConnell Thursday on what veteran Supreme Court correspondent Kenneth Jost called a “victory lap” to the University of Louisville and University of Kentucky law schools last week.

“When President Trump sent his nomination to the Senate earlier this year, as some of you know, the friends of mine in the audience, I could not have been happier,” McConnell told the audience before Gorsuch delivered a speech on his “originalist” philosophy of judging. “I don’t believe in red judges or blue judges,” Gorsuch said with a straight face. “We wear black.”

American law and justice have always suffered from a kind of cognitive dissonance. The ideal of even-handed justice is widely hailed; but everyone at some level knows that, if law in fact has two hands, it holds politics in both of them.

“Scarcely any political question arises in the United States that is not resolved, sooner or later, into a judicial question,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1835. And many judicial questions resolve, quickly, into partisan disputes.

That dissonance, however, seems particularly marked this fall. Not since the New Deal crisis of 1937 has the Supreme Court been so clearly revealed to the world as fully enmeshed in the rankest partisan politics. There seems little prospect of disengagement any time soon.

The impudent glee of Gorsuch’s supporters may account for the leaden feeling that assails me as the first Monday in October, which opens the Supreme Court’s 2017-18 term, bears down upon us. This term may resolve some crucial questions about the future of democracy in the era of authoritarianism: the role of race and religion in American immigration law; the role of partisan line-drawing in American legislative elections; the remaining scope of the battered right to vote; the depth of the law’s commitment to marriage equality and LGBT rights.

The Supreme Court that will address these issues, however, seems to me a different creature than the Court I have alternately loved, and hated, for nearly half a century.

It has been a long glide path from the exalted place the Court once held in the American mind; but we may at last have arrived at a place where it is simply another cog in the partisan-industrial complex, as “neutral” as the White House press room or the Democratic Governors Conference. I find myself fighting the impulse to identify the justice, like a member of Congress, with a partisan parenthetical on first reference.

As a Southerner growing up in the autumn of segregation, many of my first childhood memories were of adults discussing the Court. Many white adults hated and feared it; many African Americans revered it. But nobody thought of the Court as a party instrument. Some judicial liberals—such as Chief Justice Earl Warren and Justice William Brennan—were Republican appointees; some conservatives—like Justices Felix Frankfurter and Byron White—had been chosen by Democratic presidents. The Court’s decisions were sometimes exhilarating (I think of New York Times v. Sullivan, the key press-freedom case, and United States v. United States District Court, which rebuked President Richard Nixon’s claim of unlimited power to order warrantless wiretaps), and they were sometimes appalling (Buckley v. Valeo, the first campaign-finance case, started the law on the road to Citizens United; McCleskey v. Kemp concluded that overwhelming statistical evidence of racist application was simply irrelevant to the law of the death penalty).

None of them seemed like the triumph of one party.

Everyone knows, and always has known, that politics plays a role in shaping the courts. The old street definition of a federal judge is a lawyer who knows a politician. During the New Deal, the liberal wing of the Democratic party, led by President Franklin Roosevelt, mounted a sharp attack on the Court’s independence. Roosevelt proposed a “Judicial Procedures Reform” bill that, he said, would “infuse new blood into all our Courts,” allowing him to appoint up to six new “judges who will bring to the Courts a present-day sense of the Constitution.”

The Roosevelt plan was rejected by Congress, and its failure marked a sharp turn in FDR’s power in Congress. Though he reshaped the courts by appointment, never again did he, or any other political leader, seek the power to remake the institution itself along partisan lines.

Never, that is, until February 16, 2016, the day Justice Antonin Scalia died in his sleep at a remote Texas ranch. Less than an hour after Scalia’s death was announced—literally before the body could be moved—McConnell had announced a new rule. The sitting president could not name a justice, because, in essence, the ownership of the seat was to be decided by popular vote. The majority party in the Senate owned the seat; qualifications, and the Constitution, were not factors.

Even after McConnell’s challenge, Barack Obama responded to the vacancy as a president facing an adverse Senate should—with compromise and conciliation. After careful thought, he nominated a moderate justice whom the Senate’s leading Republican constitutional thinker, Senator Orrin Hatch, had called a “consensus nominee” and had pledged to support.

That did not matter. The identity of the judge was not important; a Supreme Court justice was a creature of the party in the White House, and would be solely judged on that basis. A nominee would be judged by party credentials, just like the doorkeeper of the House.

We can debate about stages on the journey—the Bork nomination, Bush v. Gore, the filibusters of Bush nominees, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s improper comments on the presidential election—but with McConnell’s announcement, and the Republican caucuses compliance in what they knew was grievously wrong, judicial nominations reached the last stop on the highway to hell.

And waiting there was Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The history is not Gorsuch’s fault. But having decided to accept a nomination so befouled by politics, Gorsuch might have displayed a sense of humility—an awareness that he took the office in a manner that millions of Americans would regard as illegitimate. It might have been seemly not to appear with McConnell; it might be even seemlier to refuse a speaking engagement at the Trump Hotel. That kind of reticence, however, is apparently not to be expected from our newest justice. He will not even pretend to care about how the losers in the process see either him, or the Court.

Autumn is always a time of loss. But this fall I feel particularly bereft. Much of my life has been involved in law, the Constitution, and the courts. A generation hence, what will be left of any of them?

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com

Author: Garrett Epps

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters in July that he doesn’t quite agree. Asked to explain to his party’s base the Senate’s lack of legislative accomplishment, McConnell said, “Well, we have a new Supreme Court justice.”

Gorsuch hasn’t commented on that statement. But he was quite happy to appear with McConnell Thursday on what veteran Supreme Court correspondent Kenneth Jost called a “victory lap” to the University of Louisville and University of Kentucky law schools last week.

“When President Trump sent his nomination to the Senate earlier this year, as some of you know, the friends of mine in the audience, I could not have been happier,” McConnell told the audience before Gorsuch delivered a speech on his “originalist” philosophy of judging. “I don’t believe in red judges or blue judges,” Gorsuch said with a straight face. “We wear black.”

American law and justice have always suffered from a kind of cognitive dissonance. The ideal of even-handed justice is widely hailed; but everyone at some level knows that, if law in fact has two hands, it holds politics in both of them.

“Scarcely any political question arises in the United States that is not resolved, sooner or later, into a judicial question,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1835. And many judicial questions resolve, quickly, into partisan disputes.

That dissonance, however, seems particularly marked this fall. Not since the New Deal crisis of 1937 has the Supreme Court been so clearly revealed to the world as fully enmeshed in the rankest partisan politics. There seems little prospect of disengagement any time soon.

The impudent glee of Gorsuch’s supporters may account for the leaden feeling that assails me as the first Monday in October, which opens the Supreme Court’s 2017-18 term, bears down upon us. This term may resolve some crucial questions about the future of democracy in the era of authoritarianism: the role of race and religion in American immigration law; the role of partisan line-drawing in American legislative elections; the remaining scope of the battered right to vote; the depth of the law’s commitment to marriage equality and LGBT rights.

The Supreme Court that will address these issues, however, seems to me a different creature than the Court I have alternately loved, and hated, for nearly half a century.

It has been a long glide path from the exalted place the Court once held in the American mind; but we may at last have arrived at a place where it is simply another cog in the partisan-industrial complex, as “neutral” as the White House press room or the Democratic Governors Conference. I find myself fighting the impulse to identify the justice, like a member of Congress, with a partisan parenthetical on first reference.

As a Southerner growing up in the autumn of segregation, many of my first childhood memories were of adults discussing the Court. Many white adults hated and feared it; many African Americans revered it. But nobody thought of the Court as a party instrument. Some judicial liberals—such as Chief Justice Earl Warren and Justice William Brennan—were Republican appointees; some conservatives—like Justices Felix Frankfurter and Byron White—had been chosen by Democratic presidents. The Court’s decisions were sometimes exhilarating (I think of New York Times v. Sullivan, the key press-freedom case, and United States v. United States District Court, which rebuked President Richard Nixon’s claim of unlimited power to order warrantless wiretaps), and they were sometimes appalling (Buckley v. Valeo, the first campaign-finance case, started the law on the road to Citizens United; McCleskey v. Kemp concluded that overwhelming statistical evidence of racist application was simply irrelevant to the law of the death penalty).

None of them seemed like the triumph of one party.

Everyone knows, and always has known, that politics plays a role in shaping the courts. The old street definition of a federal judge is a lawyer who knows a politician. During the New Deal, the liberal wing of the Democratic party, led by President Franklin Roosevelt, mounted a sharp attack on the Court’s independence. Roosevelt proposed a “Judicial Procedures Reform” bill that, he said, would “infuse new blood into all our Courts,” allowing him to appoint up to six new “judges who will bring to the Courts a present-day sense of the Constitution.”

The Roosevelt plan was rejected by Congress, and its failure marked a sharp turn in FDR’s power in Congress. Though he reshaped the courts by appointment, never again did he, or any other political leader, seek the power to remake the institution itself along partisan lines.

Never, that is, until February 16, 2016, the day Justice Antonin Scalia died in his sleep at a remote Texas ranch. Less than an hour after Scalia’s death was announced—literally before the body could be moved—McConnell had announced a new rule. The sitting president could not name a justice, because, in essence, the ownership of the seat was to be decided by popular vote. The majority party in the Senate owned the seat; qualifications, and the Constitution, were not factors.

Even after McConnell’s challenge, Barack Obama responded to the vacancy as a president facing an adverse Senate should—with compromise and conciliation. After careful thought, he nominated a moderate justice whom the Senate’s leading Republican constitutional thinker, Senator Orrin Hatch, had called a “consensus nominee” and had pledged to support.

That did not matter. The identity of the judge was not important; a Supreme Court justice was a creature of the party in the White House, and would be solely judged on that basis. A nominee would be judged by party credentials, just like the doorkeeper of the House.

We can debate about stages on the journey—the Bork nomination, Bush v. Gore, the filibusters of Bush nominees, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s improper comments on the presidential election—but with McConnell’s announcement, and the Republican caucuses compliance in what they knew was grievously wrong, judicial nominations reached the last stop on the highway to hell.

And waiting there was Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The history is not Gorsuch’s fault. But having decided to accept a nomination so befouled by politics, Gorsuch might have displayed a sense of humility—an awareness that he took the office in a manner that millions of Americans would regard as illegitimate. It might have been seemly not to appear with McConnell; it might be even seemlier to refuse a speaking engagement at the Trump Hotel. That kind of reticence, however, is apparently not to be expected from our newest justice. He will not even pretend to care about how the losers in the process see either him, or the Court.

Autumn is always a time of loss. But this fall I feel particularly bereft. Much of my life has been involved in law, the Constitution, and the courts. A generation hence, what will be left of any of them?

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com

Author: Garrett Epps

No comments:

Post a Comment