Amnesty International is calling for a criminal investigation into the oil giant Shell regarding allegations it was complicit in human rights abuses carried out by the Nigerian military.

A review of thousands of internal company documents and witness statements published on Tuesday points to the Anglo-Dutch organisation’s alleged involvement in the brutal campaign to silence protesters in the oil-producing Ogoniland region in the 1990s.

Amnesty is urging the UK, Nigeria and the Netherlands to consider a criminal case against Shell in light of evidence it claims amounts to “complicity in murder, rape and torture” – allegations Shell strongly denies.

While the cache of documents includes material Shell was forced to disclose as part of a civil case brought against the company and many of the allegations are long-standing, the review also examines some evidence which has not been previously reported.

It includes witness statements seen by the Guardian that allege Shell managed a unit of undercover police officers, trained by the Nigerian state security service, to carry out surveillance in Ogoniland after the oil company had publicly announced its withdrawal from the region.

Shell stopped operations in Ogoniland in early 1993 citing security concerns but “subsequently sought ways to re-enter the region and end the protests by the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, Mosop”, claims Amnesty.

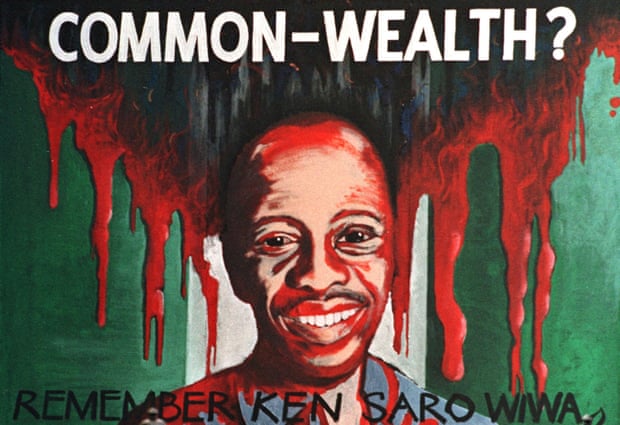

The group had been formed under the leadership of the Nigerian author and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, and pressed for a bill of rights to gain political and economic autonomy for the indigenous population and protect their homeland from “an ecological disaster”.

In 1993 its mounting campaign was successful in forcing the oil company to quit the region. But mass protests ensued after Shell pushed ahead with plans to lay a new pipeline through the area.

On 30 April the same year troops guarding Shell’s contractors opened fire on protesters injuring 11 people, and a man was fatally shot at Nonwa village in a separate incident several days later.

In the brutal backlash that followed by Nigeria’s military police, about 1,000 people were killed and 30,000 made homeless after villages were destroyed.

Audrey Gaughran, director of global issues at Amnesty, said: “The evidence shows Shell repeatedly encouraged the Nigerian military to deal with community protests, even when it knew the horrors this would lead to – unlawful killings, rape, torture and the burning of villages.

“It is indisputable that Shell played a key role in the devastating events in Ogoniland in the 1990s but we now believe there are grounds for a criminal investigation.”

She added: “Bringing all the evidence together was the first step. We will now be preparing a criminal file to submit to the relevant authorities with a view to prosecution.”

The organisation alleges Shell gave the military “logistical support” including transport and, on at least one occasion, paid a military commander notorious for human rights violations.

Amnesty claims documents, shared with the Guardian, reveal that in March 1994 the company made a payment of more than $900 to a special government unit created to “restore order” in Ogoniland.

This was just 10 days after the unit commander ordered the shooting of unarmed protesters outside Shell’s regional headquarters in Port Harcourt.

Other evidence collated as part of the review points to Shell’s apparent links with Nigeria’s internal security agency, the SSS.

Shell has publicly said the police force seconded for its protection was used “solely to guard” its staff and property but depositions obtained as part of legal proceedings against the company are claimed to show this unit had close ties with the SSS.

George Ukpong, former head of security for Shell’s eastern region, who supervised the force instructed by Shell, said: “Each day I come to work … I will phone the director of state security. Exchange of information.”

One of his key sources was a unit of the force seconded to Shell, which would gather information by entering sensitive areas in plain clothes. “I regard them as my informants,” he said.

In the witness statement Ukpong went on to explain how the SSS provided this unit with training.

He said: “We invited their training wing, come in, gather a number of our intelligence team, we have a section in the supernumeracy police who are supposed to look at these areas. Then, basically, they sat them down and gave them the principles of surveillance and information gathering.”

Mark Dummett, a researcher for Amnesty, said: “The fact Shell was running a shady undercover unit and then passing on information to the Nigerian security agency is incredibly disturbing.

“This was a time when Nigeria was cracking down on peaceful protesters, and there must have been a risk that information gathered by Shell’s secret spy unit contributed to grave human rights violations.

He added: “The revelations show how close and insidious the relationship was between the oil company and the Nigerian state, and Shell has serious questions to answer.”

The Nigerian government’s campaign against the Ogoni people culminated in the execution 22 years ago of nine Ogoni men, including Saro-Wiwa, who had led the protests. Their deaths sparked a global outcry with claims their trial had been unfair.

In June this year the widows of four of the men filed a writ against Shell in the Netherlands, accusing the company of complicity in their deaths.

An individual or company can be held criminally responsible for a crime if they encourage, enable, exacerbate or facilitate it.

Amnesty’s new report, A Criminal Enterprise?, alleges that Shell was involved in crimes committed in Ogoniland in this way.

In his final words to the tribunal that convicted him, Ken Saro-Wiwa warned that Shell would face its own day in court.

Now Amnesty says: “We are determined to make this happen. Justice must be – for Ken Saro-Wiwa and for the thousands of others whose lives were ruined by Shell’s destruction of Ogoniland.”

A spokesperson for the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC) said the allegations have always been denied by Shell in the strongest possible terms.

They said: “The executions of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his fellow Ogonis in 1995 were tragic events that were carried out by the military government in power at the time.

“We were shocked and saddened when we heard the news. Shell appealed to the Nigerian government to grant clemency. To our deep regret, that appeal, and the appeals made by many others … went unheard.”

They added: “Support for human rights in line with the legitimate role of business is fundamental to Shell’s core values of honesty, integrity and respect for people. Amnesty’s allegations concerning SPDC are false and without merit. SPDC did not collude with the authorities to suppress community unrest and in no way encouraged or advocated any act of violence in Nigeria. We believe that the evidence will show clearly that Shell was not responsible for these tragic events.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com

Author: Hannah Summers

A review of thousands of internal company documents and witness statements published on Tuesday points to the Anglo-Dutch organisation’s alleged involvement in the brutal campaign to silence protesters in the oil-producing Ogoniland region in the 1990s.

Amnesty is urging the UK, Nigeria and the Netherlands to consider a criminal case against Shell in light of evidence it claims amounts to “complicity in murder, rape and torture” – allegations Shell strongly denies.

While the cache of documents includes material Shell was forced to disclose as part of a civil case brought against the company and many of the allegations are long-standing, the review also examines some evidence which has not been previously reported.

It includes witness statements seen by the Guardian that allege Shell managed a unit of undercover police officers, trained by the Nigerian state security service, to carry out surveillance in Ogoniland after the oil company had publicly announced its withdrawal from the region.

Shell stopped operations in Ogoniland in early 1993 citing security concerns but “subsequently sought ways to re-enter the region and end the protests by the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, Mosop”, claims Amnesty.

The group had been formed under the leadership of the Nigerian author and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, and pressed for a bill of rights to gain political and economic autonomy for the indigenous population and protect their homeland from “an ecological disaster”.

In 1993 its mounting campaign was successful in forcing the oil company to quit the region. But mass protests ensued after Shell pushed ahead with plans to lay a new pipeline through the area.

On 30 April the same year troops guarding Shell’s contractors opened fire on protesters injuring 11 people, and a man was fatally shot at Nonwa village in a separate incident several days later.

In the brutal backlash that followed by Nigeria’s military police, about 1,000 people were killed and 30,000 made homeless after villages were destroyed.

Audrey Gaughran, director of global issues at Amnesty, said: “The evidence shows Shell repeatedly encouraged the Nigerian military to deal with community protests, even when it knew the horrors this would lead to – unlawful killings, rape, torture and the burning of villages.

“It is indisputable that Shell played a key role in the devastating events in Ogoniland in the 1990s but we now believe there are grounds for a criminal investigation.”

She added: “Bringing all the evidence together was the first step. We will now be preparing a criminal file to submit to the relevant authorities with a view to prosecution.”

The organisation alleges Shell gave the military “logistical support” including transport and, on at least one occasion, paid a military commander notorious for human rights violations.

Amnesty claims documents, shared with the Guardian, reveal that in March 1994 the company made a payment of more than $900 to a special government unit created to “restore order” in Ogoniland.

This was just 10 days after the unit commander ordered the shooting of unarmed protesters outside Shell’s regional headquarters in Port Harcourt.

Other evidence collated as part of the review points to Shell’s apparent links with Nigeria’s internal security agency, the SSS.

Shell has publicly said the police force seconded for its protection was used “solely to guard” its staff and property but depositions obtained as part of legal proceedings against the company are claimed to show this unit had close ties with the SSS.

George Ukpong, former head of security for Shell’s eastern region, who supervised the force instructed by Shell, said: “Each day I come to work … I will phone the director of state security. Exchange of information.”

One of his key sources was a unit of the force seconded to Shell, which would gather information by entering sensitive areas in plain clothes. “I regard them as my informants,” he said.

In the witness statement Ukpong went on to explain how the SSS provided this unit with training.

He said: “We invited their training wing, come in, gather a number of our intelligence team, we have a section in the supernumeracy police who are supposed to look at these areas. Then, basically, they sat them down and gave them the principles of surveillance and information gathering.”

Mark Dummett, a researcher for Amnesty, said: “The fact Shell was running a shady undercover unit and then passing on information to the Nigerian security agency is incredibly disturbing.

“This was a time when Nigeria was cracking down on peaceful protesters, and there must have been a risk that information gathered by Shell’s secret spy unit contributed to grave human rights violations.

He added: “The revelations show how close and insidious the relationship was between the oil company and the Nigerian state, and Shell has serious questions to answer.”

The Nigerian government’s campaign against the Ogoni people culminated in the execution 22 years ago of nine Ogoni men, including Saro-Wiwa, who had led the protests. Their deaths sparked a global outcry with claims their trial had been unfair.

In June this year the widows of four of the men filed a writ against Shell in the Netherlands, accusing the company of complicity in their deaths.

An individual or company can be held criminally responsible for a crime if they encourage, enable, exacerbate or facilitate it.

Amnesty’s new report, A Criminal Enterprise?, alleges that Shell was involved in crimes committed in Ogoniland in this way.

In his final words to the tribunal that convicted him, Ken Saro-Wiwa warned that Shell would face its own day in court.

Now Amnesty says: “We are determined to make this happen. Justice must be – for Ken Saro-Wiwa and for the thousands of others whose lives were ruined by Shell’s destruction of Ogoniland.”

A spokesperson for the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC) said the allegations have always been denied by Shell in the strongest possible terms.

They said: “The executions of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his fellow Ogonis in 1995 were tragic events that were carried out by the military government in power at the time.

“We were shocked and saddened when we heard the news. Shell appealed to the Nigerian government to grant clemency. To our deep regret, that appeal, and the appeals made by many others … went unheard.”

They added: “Support for human rights in line with the legitimate role of business is fundamental to Shell’s core values of honesty, integrity and respect for people. Amnesty’s allegations concerning SPDC are false and without merit. SPDC did not collude with the authorities to suppress community unrest and in no way encouraged or advocated any act of violence in Nigeria. We believe that the evidence will show clearly that Shell was not responsible for these tragic events.”

Original Article

Source: theguardian.com

Author: Hannah Summers

No comments:

Post a Comment