There was once a time when school children would hang out at the Al-Karama library in Cairo’s bustling, impoverished Dar El Salam neighborhood. They sought escape from the polluted drudgery of slum life, or just a safe space to finish their homework. But for almost a year now, the library’s decrepit maroon garage door has been rolled shut: In December 2016, Egyptian security forces raided the library and three of its sister branches after deeming them seditious spaces.

The government’s assessment of the libraries stemmed largely from the work of their founder, Gamal Eid, a human-rights lawyer with a high, lilting voice. After Egypt’s cataclysmic revolution in 2011, Eid used his own money to open the library and five others like it. The name he gave them, Al-Karama, means “dignity” in Arabic.

On the day of the Dar El Salam raid, Eid and a group of volunteers held incensed children back from hurling rocks at the police. Fearing further retaliation, he decided to close the other three branches. The six locations have been shut down for the past year. Only a portion of the books has been recovered from the police.

Eid now spends his days defending unfairly imprisoned Egyptians. As one of Egypt’s most visible human-rights activists (with a one-million-strong Twitter following), he has been barred from leaving Egypt since February of last year; his assets have also been frozen. “The state is contra human rights [and against] any independent voices. And I understand this logic. But what really breaks me is why would you specifically target … libraries” that serve thousands of children, he told me. “You have hurt them.”

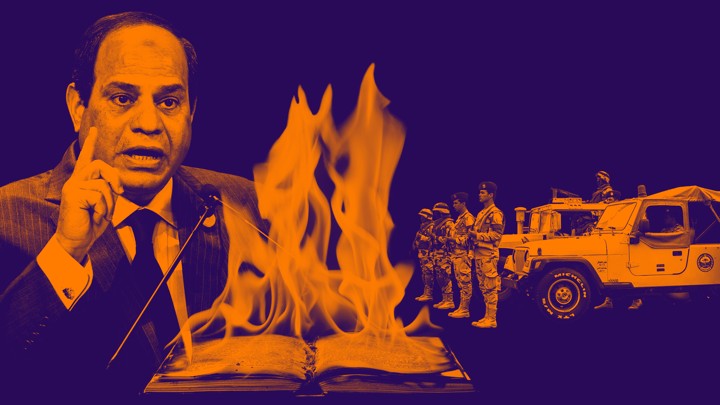

This logic has animated the repressive regime of general-turned-president Abdel Fattah El Sisi, who overthrew Islamist president Mohammed Morsi in July 2013. At first, Sisi promised political stability and economic prosperity. But those promises remain unmet, and there are signs that his grip on power is slipping: A poll last year showed a 14 percent drop in his public approval after he slashed subsidies and inflation spiked dramatically.

With an election approaching in 2018, Sisi has resorted to stifling dissent and galvanizing his security agencies and the military-industrial complex to help ensure that he will run unopposed. He has used his vast security apparatus to crack down on opposition politicians, including the Brotherhood, more vehemently the longer he has been in power. Meanwhile, analysts warn that if he remains focused on suppression rather than the economy, Egypt will implode.

Even by the repressive standards of the current regime, November was an absurd month. Sherine Abdel Wahab, a popular Egyptian diva and judge on the Arab version of the talent show The Voice, will go to court in December for cracking a joke about the Nile River’s severe contamination. Authorities also banned The Nile Hilton Incident from screening at a local film festival. The Sundance-award-winning fictional film tells the story of an investigation into the killing of a night-club singer at the Nile Hilton Hotel, and delves into the underbelly of Cairo’s corrupt political elite. The festival organizers cited “circumstances beyond our control” as their sole justification for cancelling the screening. Just last week, the police raided another art house theater that was screening the film.

But nothing seems to disturb Egypt’s ruling cadres more than the written word. The recent litany of bans and shutdowns, including blocking hundreds of web pages online, illustrates what Cambridge University’s Khaled Fahmy, a prolific historian of the Middle East, called “an alarmist moment of crisis,” one in which Egypt’s authoritarian state of emergency laws have turned something as simple as reading into a dangerous act. “Free press and freedom of information … are essential ingredients of any democratic system. The regime and many segments of society do not see it this way—they see the exact opposite. They see at times of crises we have to have absolute unity,” Fahmy told me.

On November 23, Gamal Abdel Hakim, a leftist political activist on his university campus, was sentenced to five years in jail under a counter-terrorism law for possessing a copy of Karl Marx’s Value, Price and Profit when he was arrested from his home earlier this year. A few days earlier on November 19, Interior Ministry officers raided downtown Cairo’s Dar Merit Publishing House, which champions young authors and serves as a refuge for revolutionaries, and detained a volunteer, accusing him of possessing and selling unregistered books. It is the latest in a series of bookshops and libraries that have been shut down in recent months. El Balad (or “The Country”), another trendy left-leaning bookstore frequented by Cairo’s literati, was also forced to close in November. Alef, a commercial bookstore chain, had its assets confiscated earlier this month on suspicion of the owner’s alleged links to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Under its various modern rulers, but more so today, Egypt has sought to present a palatable but conservative version of Islam that the masses can embrace. Sisi prefers conservative Islamists who he can control over secular dissidents—chiefly writers—who threaten his rule. He has worked with the ultraconservative Salafis to achieve short-term political goals, while at the same time trumpeting his fight against an emboldened insurgency in the Sinai to foreign leaders.

Within Sisi’s approach to Islam, censorship remains key. In addition to going after the Muslim Brotherhood, he has locked up thousands of youth and other perceived dissidents. His brutal crackdown has ensnared over 40,000 prisoners of different political stripes. In the security-first mindset of the Sisi regime, writers and other dissidents pose a considerable threat: They have the ability to make the larger population question his policies.

At the General Egyptian Book Organization, the state’s publishing house, this ideological tenor holds steady. “The book I’m publishing has to guarantee that there are no ideas that lead to militancy,” Soheir Almasadfa, chairwoman of cultural and publishing projects at the state body, told me. She denied that censorship was rife in Egypt, instead trumpeting Egypt’s glorious literary heritage in comparison to today’s younger, more experimental writers. “I am also against publishing books that are responsible for the decaying civilizational moment that we are living in Egypt. These books belong on the curb,” she added.

Ahmed Naji, a PEN-award-winning novelist ensnared in a Kafkaesque legal limbo, also sees an Egypt mired in a cultural malaise, but from a vastly different perspective. A chapter from his acclaimed novel Using Life, released in November this year in English, was published in August 2014 in a state-affiliated literary journal which he worked for. It was considered salacious enough to land him in prison in 2016, launching a moral panic around his sexually-loaded words.

He spent a year in prison for “offending public modesty” for his dystopian and heavily sexualized vernacular that is at once satirical and exudes an air of non-chalance—much like himself. He has since been released from prison. “Maybe they imprisoned me because I am hot shit,” he told me with a smirk. He is frustrated with not being able to leave Egypt, due to a suspended two-year verdict hanging over his head.

Fahmy is optimistic that the current repressive period is already creating burgeoning subversive spaces of critical resistance. “Within the readership there actually is a more healthy and critical reception of books and engagement with them [than before]. The reading public hasn’t expanded but deepened.”

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com

Author: Farid Y. Farid

The government’s assessment of the libraries stemmed largely from the work of their founder, Gamal Eid, a human-rights lawyer with a high, lilting voice. After Egypt’s cataclysmic revolution in 2011, Eid used his own money to open the library and five others like it. The name he gave them, Al-Karama, means “dignity” in Arabic.

On the day of the Dar El Salam raid, Eid and a group of volunteers held incensed children back from hurling rocks at the police. Fearing further retaliation, he decided to close the other three branches. The six locations have been shut down for the past year. Only a portion of the books has been recovered from the police.

Eid now spends his days defending unfairly imprisoned Egyptians. As one of Egypt’s most visible human-rights activists (with a one-million-strong Twitter following), he has been barred from leaving Egypt since February of last year; his assets have also been frozen. “The state is contra human rights [and against] any independent voices. And I understand this logic. But what really breaks me is why would you specifically target … libraries” that serve thousands of children, he told me. “You have hurt them.”

This logic has animated the repressive regime of general-turned-president Abdel Fattah El Sisi, who overthrew Islamist president Mohammed Morsi in July 2013. At first, Sisi promised political stability and economic prosperity. But those promises remain unmet, and there are signs that his grip on power is slipping: A poll last year showed a 14 percent drop in his public approval after he slashed subsidies and inflation spiked dramatically.

With an election approaching in 2018, Sisi has resorted to stifling dissent and galvanizing his security agencies and the military-industrial complex to help ensure that he will run unopposed. He has used his vast security apparatus to crack down on opposition politicians, including the Brotherhood, more vehemently the longer he has been in power. Meanwhile, analysts warn that if he remains focused on suppression rather than the economy, Egypt will implode.

Even by the repressive standards of the current regime, November was an absurd month. Sherine Abdel Wahab, a popular Egyptian diva and judge on the Arab version of the talent show The Voice, will go to court in December for cracking a joke about the Nile River’s severe contamination. Authorities also banned The Nile Hilton Incident from screening at a local film festival. The Sundance-award-winning fictional film tells the story of an investigation into the killing of a night-club singer at the Nile Hilton Hotel, and delves into the underbelly of Cairo’s corrupt political elite. The festival organizers cited “circumstances beyond our control” as their sole justification for cancelling the screening. Just last week, the police raided another art house theater that was screening the film.

But nothing seems to disturb Egypt’s ruling cadres more than the written word. The recent litany of bans and shutdowns, including blocking hundreds of web pages online, illustrates what Cambridge University’s Khaled Fahmy, a prolific historian of the Middle East, called “an alarmist moment of crisis,” one in which Egypt’s authoritarian state of emergency laws have turned something as simple as reading into a dangerous act. “Free press and freedom of information … are essential ingredients of any democratic system. The regime and many segments of society do not see it this way—they see the exact opposite. They see at times of crises we have to have absolute unity,” Fahmy told me.

On November 23, Gamal Abdel Hakim, a leftist political activist on his university campus, was sentenced to five years in jail under a counter-terrorism law for possessing a copy of Karl Marx’s Value, Price and Profit when he was arrested from his home earlier this year. A few days earlier on November 19, Interior Ministry officers raided downtown Cairo’s Dar Merit Publishing House, which champions young authors and serves as a refuge for revolutionaries, and detained a volunteer, accusing him of possessing and selling unregistered books. It is the latest in a series of bookshops and libraries that have been shut down in recent months. El Balad (or “The Country”), another trendy left-leaning bookstore frequented by Cairo’s literati, was also forced to close in November. Alef, a commercial bookstore chain, had its assets confiscated earlier this month on suspicion of the owner’s alleged links to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Under its various modern rulers, but more so today, Egypt has sought to present a palatable but conservative version of Islam that the masses can embrace. Sisi prefers conservative Islamists who he can control over secular dissidents—chiefly writers—who threaten his rule. He has worked with the ultraconservative Salafis to achieve short-term political goals, while at the same time trumpeting his fight against an emboldened insurgency in the Sinai to foreign leaders.

Within Sisi’s approach to Islam, censorship remains key. In addition to going after the Muslim Brotherhood, he has locked up thousands of youth and other perceived dissidents. His brutal crackdown has ensnared over 40,000 prisoners of different political stripes. In the security-first mindset of the Sisi regime, writers and other dissidents pose a considerable threat: They have the ability to make the larger population question his policies.

At the General Egyptian Book Organization, the state’s publishing house, this ideological tenor holds steady. “The book I’m publishing has to guarantee that there are no ideas that lead to militancy,” Soheir Almasadfa, chairwoman of cultural and publishing projects at the state body, told me. She denied that censorship was rife in Egypt, instead trumpeting Egypt’s glorious literary heritage in comparison to today’s younger, more experimental writers. “I am also against publishing books that are responsible for the decaying civilizational moment that we are living in Egypt. These books belong on the curb,” she added.

Ahmed Naji, a PEN-award-winning novelist ensnared in a Kafkaesque legal limbo, also sees an Egypt mired in a cultural malaise, but from a vastly different perspective. A chapter from his acclaimed novel Using Life, released in November this year in English, was published in August 2014 in a state-affiliated literary journal which he worked for. It was considered salacious enough to land him in prison in 2016, launching a moral panic around his sexually-loaded words.

He spent a year in prison for “offending public modesty” for his dystopian and heavily sexualized vernacular that is at once satirical and exudes an air of non-chalance—much like himself. He has since been released from prison. “Maybe they imprisoned me because I am hot shit,” he told me with a smirk. He is frustrated with not being able to leave Egypt, due to a suspended two-year verdict hanging over his head.

Fahmy is optimistic that the current repressive period is already creating burgeoning subversive spaces of critical resistance. “Within the readership there actually is a more healthy and critical reception of books and engagement with them [than before]. The reading public hasn’t expanded but deepened.”

Original Article

Source: theatlantic.com

Author: Farid Y. Farid

No comments:

Post a Comment