On a Thursday afternoon in November 2015, a light snow was falling outside the windows of the Ecuadorian embassy in London, despite the relatively warm weather, and Julian Assange was inside, sitting at his computer and pondering the upcoming 2016 presidential election in the United States.

In little more than a year, WikiLeaks would be engulfed in a scandal over how it came to publish internal emails that damaged Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, and the extent to which it worked with Russian hackers or Donald Trump’s campaign to do so. But in the fall of 2015, Trump was polling at less than 30 percent among Republican voters, neck-and-neck with neurosurgeon Ben Carson, and Assange spoke freely about why WikiLeaks wanted Clinton and the Democrats to lose the election.

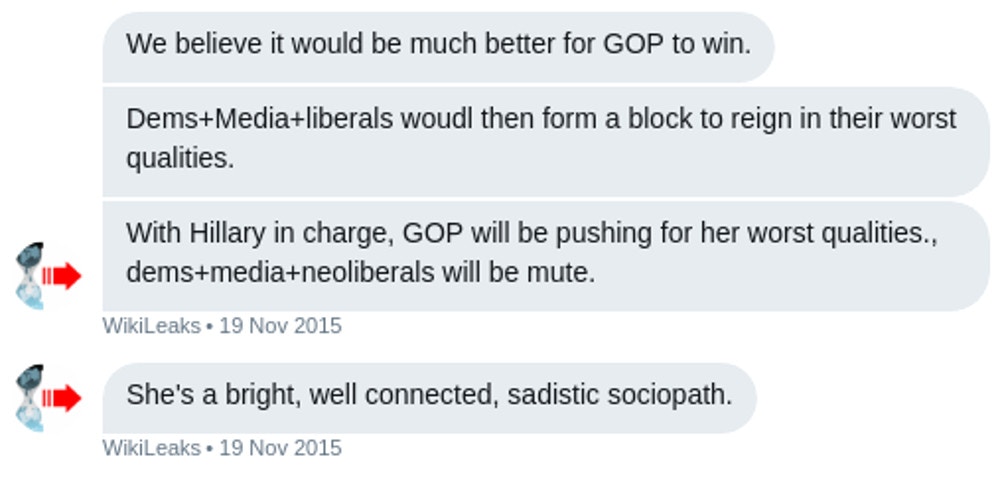

“We believe it would be much better for GOP to win,” he typed into a private Twitter direct message group to an assortment of WikiLeaks’ most loyal supporters on Twitter. “Dems+Media+liberals woudl then form a block to reign in their worst qualities,” he wrote. “With Hillary in charge, GOP will be pushing for her worst qualities., dems+media+neoliberals will be mute.” He paused for two minutes before adding, “She’s a bright, well connected, sadistic sociopath.”

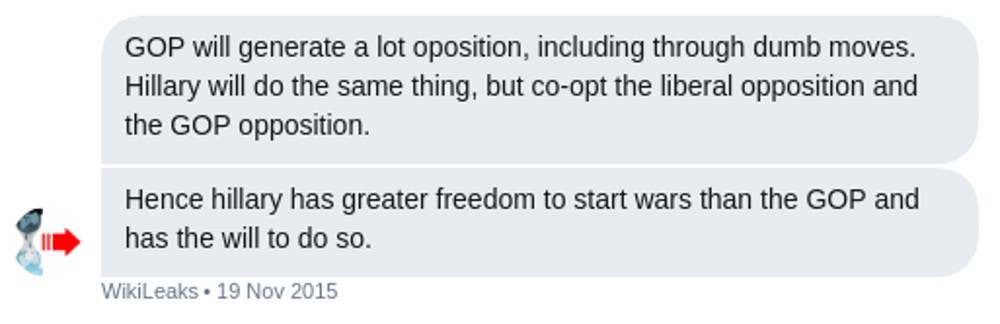

Assange’s thinking appeared to be rooted not in ideological agreement with the right wing in the U.S., but in the tactical idea that a Republican president would face more resistance to an aggressive military posture than an interventionist President Hillary Clinton would.

A few more months into the primary season, after Super Tuesday, Assange decried the idea of Clinton in the “whitehouse with her bloodlutt and amitions of empire with hawkish liberal-interventionist appointees like [Anne-Marie] Slaughter and digital expansionists such as Google integrated into the power structure. Then the republicans and trump in opposition constantly saying she’s weak and not invading enough.”

WikiLeaks has not made a secret of its opposition to Clinton. Assange had raised the possibility of her resigning as secretary of state in 2010, after WikiLeaks released its cache of U.S. diplomatic cables, and had also harshly criticized Clinton’s support for military action in Libya and the Middle East.

Still, Twitter messages obtained by The Intercept provide an unfiltered window into WikiLeaks’ political goals before it dove into the white-hot center of the presidential election. The messages also reveal a running theme of sexism and misogyny, contain hints of anti-Semitism, and underline Assange’s well-documented obsession with his public image.

The chats are from a direct message group between WikiLeaks and about 10 of its online boosters, described as a “low security channel for some very long term and reliable supporters who are on twitter.” Perhaps because of the “low security” designation, the chats do not shed much light on the most sensitive questions surrounding WikiLeaks and the 2016 election. They don’t reveal anything new about WikiLeaks’ relationship with the Trump campaign, although they are consistent with the group’s public statements casting doubt on claims by former Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone that he had advanced knowledge of the group’s anti-Clinton leaks. The chats don’t illuminate any connections with the Russian government or tell us anything about the identity of the source who provided WikiLeaks with emails from the Democratic National Committee and Clinton campaign chair John Podesta.

The archive spans from May 2015 through November 2017 and includes over 11,000 messages, more than 10 percent of them written from the WikiLeaks account. With this article, The Intercept is publishing newsworthy excerpts from the leaked messages.

A former supporter of and volunteer for WikiLeaks, who goes by the name “Hazelpress” (The Intercept does not know the person’s real name), set up the direct message group in mid-2015 and later decided to leak its contents to the media after news broke that WikiLeaks had secretly corresponded with Donald Trump Jr. during the election, urging candidate Trump to reject the results as rigged if he lost and requesting that the president-elect use his connections to get Assange an Australian ambassadorship. “At this point, considering the power exercised by WikiLeaks, [disclosing] literally anything Assange says is in the public interest,” Hazelpress told The Intercept, including Assange’s political position during the 2016 election, since “WikiLeaks purports to be a neutral transparency organization.”

One of the authors of this article verified the authenticity of the Twitter group messages by logging in using Hazelpress’s credentials. Throughout this article, The Intercept assumes that the WikiLeaks account is controlled by Julian Assange himself, as is widely understood, and that he is the author of the messages, referring to himself in the third person majestic plural, as he often does. The Intercept has also preserved typographical errors in quoted material.

WikiLeaks did not respond to a request for comment, sent several days before publication.

Disclosure: One of the authors of this article, Micah Lee, along with The Intercept’s co-founding editors Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, is a member of Freedom of the Press Foundation’s board of directors. For years, Freedom of the Press Foundation processed payments on behalf of WikiLeaks to bypass the financial censorship that the organization was facing. The foundation ceased doing so in December, stating that a blockade by credit card companies and PayPal had ended, but that the group still “strongly opposes any prosecution of WikiLeaks or Assange for their publishing activities.”Assange called the move “politically induced financial censorship” and alleged it was propelled by personal animosity from Lee, with whom he has clashed on Twitter.

The 2016 Election

Beyond the statement that Clinton was a “sadistic sociopath” and the explanation for why “it would be much better for GOP to win,” Assange surfaced other opinions on Clinton in the Twitter group:

After Super Tuesday, when Trump was leading in the Republican primary and Bernie Sanders suffered big losses to Clinton in the Democratic primary, Assange posted, “Perhaps Hillary will have a stroke.”

Assange believed that Clinton’s “role in the war in Libya is what should bring her down, however, the GOP is too close to others who have benefited to exploit this, itseems. That Hillary helped to sew the foundation for ISIS against pentagon generals advice seems huge. But the GOP resolutely ignores it. Hillary has so muc hslime on her shirt it is now hard to make dirt stick.” (Any ability by the Republican Party to leverage Libya against Clinton would have weakened further after Trump, who supported the Libya intervention, became the nominee.)

Some of the messages on Clinton are threaded with crass sexual allusions. In a publicly released State Department email that WikiLeaks re-published, Hillary Clinton asked her Chief of Staff Cheryl Mills, “What does ‘fubar’ mean?” Mills replied, “Fubar is unprintable on civil email.” (It stands for “fucked up beyond all recognition.”) Assange found this amusing. “WikiLeaks took Hillary’s FUBAR virginity,” the WikiLeaks account posted. “LOL. A well-deserved taking,” a Twitter interlocutor replied.

In the final months of the 2016 election, Stone repeatedly claimed that he had insider knowledge about WikiLeaks’ upcoming release of hacked emails. In early August 2016, Stone told a Florida Republican Party group, “I actually have communicated with Assange, including tweeting that ‘it will soon the [sic] Podesta’s time in the barrel’ before WikiLeaks published its cache of Podesta emails.” In the private Twitter group, WikiLeaks dismissed Stone’s claims, just as it had publicly. “Stone is a bullshitter,” Assange posted. “Trying to a) imply that he knows anything b) that he contributed to our hard work.”

In the following months, Stone continued to publicly claim he had “backchannel communications” with Assange.

Perspective on Russia

In June 2015, Assange emphasized the weakness of Russia’s geopolitical position relative to the United States. He told the Twitter group that the Kremlin is paranoid about foreign-funded NGOs because they push “invading ‘western’ cultural practices like gays and the internet,” which in turn pushes Russia to become more authoritarian. Russia was “on the defensive and terrified as the the US produces its next generation weapons and enroaches inexorably.” He further stated that all of Russia’s foreign military bases were under threat, and that “the U.S. hacks the hell out of it, and attempts to foment an orange revolution in an explicitly stated policy of regime change.”

Meanwhile, Assange maintained, Russia had only “minor imperialistic goals in its near abroad.”

“Be the Troll You Want to See in the World”

A major focus of the private Twitter group was strategizing online attack campaigns, including creating false identities, something that Assange explicitly encouraged.

Assange philosophized on how to approach such activities in conversation with a WikiLeaks supporter who told the group that Scottish Member of Parliament Paul Monaghan had retweeted her. The supporter added that others in the group should tweet at Monaghan as well to try for more retweets. Assange responded, “Exactly what we were hoping for. Be the troll you want to see in the world.”

Discussing another British politician, Assange suggested that the supporter change her account avatar to a “pretty blonde,” or a “dead actress if you want plausible deniability,” or to just create a new sock puppet account for trolling.

In another instance, Assange asked the group to “please troll this BBC idiot,” referring to journalist Chris Cook, who had been tweeting caustic messages about Assange that day. “Our interest is in having inflamitory tweets from him about JA/WL that we can use in legal cases to show that a toxic climate exists the UK (in the UK),” the next messages read.

“I don’t really remember his people causing me any issues,” Cook told The Intercept when asked about the messages.

“But He’s Jewish”

The direct messages from Assange also include an attack with anti-Semitic undertones against an Associated Press journalist.

In August 2016, AP reporter Raphael Satter tweeted a story he helped write about the harm caused when WikiLeaks publishes private information about individuals. “He’s always ben a rat,” Assange posted in the Twitter group in response. “But he’s jewish and engaged with the ((()))) issue.”

The parentheses refer to a neo-Nazi meme called “echoes,” which identifies Jews online by surrounding their names with three parentheses. In response to the meme, many Jewish people and some allies began to bracket their names on Twitter in a show of solidarity.

Satter continued to post negative tweets about WikiLeaks after promoting his story. “Bog him down. Get him to show statements of his bias,” Assange wrote, encouraging his supporters to start trolling. (Satter declined to comment for this article.)

WikiLeaks has faced charges of anti-Semitism before. In 2013, former WikiLeaks volunteer James Ball explained that he left the group over what he said was Assange’s close relationship with the Holocaust denier Israel Shamir; among other things, Ball alleged that Assange gave Shamir early access to the cache of U.S. State Department cables. Former WikiLeaks spokesperson Daniel Domscheit-Berg raised similar concerns about Shamir. Assange has downplayed WikiLeaks’ relationship with Shamir and denied giving him cable access.

In July 2016, a month before calling Satter a rat in the private Twitter group, WikiLeaks was criticized for posting a tweet suggesting that its critics were Jewish, again making use of the “echoes.”

An account in the London Review of Books by the would-be ghostwriter of Assange’s autobiography, Andrew O’Hagan, said that, amid preparations for the book in 2011, Assange had “uttered, late at night … many sexist or anti-Semitic remarks,” of which O’Hagan retained transcripts.

“The Accusation Industry Is Highly Profitable”

For years, Sweden had tried to extradite Assange from the United Kingdom in order to question him about allegations of rape and molestation. As of May 2017, Sweden is no longer seeking his extradition, and, according to emails exchanged with U.K. prosecutors, tried to drop extradition proceedings against him beginning in 2013, but were discouraged from doing so by prosecutors in the United Kingdom — where, nine months after Sweden’s extradition request was formally dropped, Assange still has an active arrest warrant.

Assange and his lawyers framed the sexual assault allegations as politically motivated, believing that if he were extradited, Sweden would send him to the United States, where he would face espionage charges related to his WikiLeaks work. This U.S. threat is the reason Ecuador has granted him asylum.

The Twitter group was intently focused on Assange’s sexual assault case, discussing how to discredit lawyers representing Assange’s accusers and journalists who covered the case in a manner unfavorable to Assange.

For instance, the group went after Elisabeth Fritz, a lawyer representing one of the women who has accused Assange of sexual assault. “Check out the sort of creature Fritz is,” Assange posted, linking to her firm’s website, which featured this photo.

Assange theorized that Swedish policies encouraged lawyers to take on rape cases for easy money and “public relations.”

“So the accusation industry is highly profitable,” he concluded. “Almost nothing to do other than bill the state for advertising your own law firm.”

Assange went on to accuse Fritz of working closely with Marianne Ny, Sweden’s chief prosecutor, to “tag-team the accused.”

Several hours later, the group was still angry about the courtroom photograph on Fritz’s website. “Money, influence, glamour for women helping women imprison men,” Assange wrote. “It may not be your type of feminism, but they don’t cae.”

Fritz told The Intercept that “WikiLeaks and Assange have, and continue to, deliberately spread false information in an attempt to turn public opinion against the women accusing Assange of sexual offenses, cast doubt on the accusations, and to discredit myself and the Swedish legal system.” She went on to say, “The leaked messages clearly show the level of contempt for women and disregard for the rule of law that WikiLeaks have.” (Ny declined to comment.)

Other women who crossed WikiLeaks came in for similarly gendered treatment: British blogger Laurie Penny was dismissed by Assange as a “fake leftist, and a manipulative, predatory exhibitionist” and called a member of the “cliterati.” The group also spent weeks in 2015 trying to preempt a Guardian article from Jessica Valenti about one of Assange’s accusers.

Asked to comment, Penny said in an email, “We don’t require Wikileaks to be the arbiter of what our feminist politics should be. I really cannot overemphasize how little I care what Julian Assange thinks about anything I do.”

Valenti wrote, “These messages speak for themselves: This is a powerful organization strategizing to discredit me and a brave woman who simply wanted to share her story.”

“Revenge Porn Against Jake”

The Twitter group also engaged in heated discussions of Laura Poitras’s documentary about WikiLeaks called “Risk.” Poitras had screened an early version of her film in the spring of 2016. In the Twitter group, Assange instructed supporters to add “nasty/damaging review quotes” to a collaborative document to argue for “edits of misleading material” before the film was released to the general public. “Risk” turned a critical eye on Assange’s attitudes toward his alleged sexual assault victims in Sweden. Assange, meanwhile, asserted that Poitras had broken various agreements she had made in order to gain access to WikiLeaks, a claim that Poitras has denied.

“Risk” also featured Jacob Appelbaum, a WikiLeaks volunteer and former employee of the nonprofit that publishes the Tor anonymity software. Beginning in June 2016, members of the Tor community came forward with accusations of rape and sexual assault against Appelbaum. The Tor Project confirmed that the sexual misconduct allegations were credible, and Appelbaum resigned, though he has denied all of the allegations and no criminal charges have been filed.

Poitras re-edited her film to address the charges and include references to WikiLeaks’ role in the 2016 election. The final version of “Risk” was released in May 2017. In it, Poitras discloses that she and Appelbaum had “been involved briefly in 2014” and that after they ended their relationship, “he was abusive to someone close to me.”

Amid the controversy, Assange accused Poitras of seeking profit and going after an ex. As the early media coverage of the final release of “Risk” started to appear, Assange wrote that it “seems to have transformed into some kind of revenge porn against jake.”

In the Twitter group, Assange never seems to entertain the idea that Poitras actually believed the women who accused Appelbaum; instead he stated that she was motivated by money and Oscar ambitions. “Profit matrix changed due to DNC and jakegate,” Assange wrote. “She’d have been exposed as sleeping with her subjects and making them appear positive after jakegate, so she had to attack them instead of defend against accusations of crossing the line.”

“Misogyny, self-pity, and calculated lies from Assange? That’s no surprise after our dealings with him and his lawyers on ‘Risk,'” Brenda Coughlin, producer of “Risk,” told The Intercept. “They repeatedly sought to censor the film to get us to remove Assange’s own sexist comments.”

In another exchange, Assange casts doubt on the charges against Appelbaum in the course of slamming the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Executive Director Cindy Cohn as a “stupid bay area neo-liberal” and “part of the anti-Jacob persecutrixity.” (Cohn declined to comment.)

Chelsea Manning and Gender

Some discussions in the Twitter group revolve around Chelsea Manning, formerly known as Bradley Manning, once WikiLeaks’ most significant source. Manning served seven years of a 35-year sentence for leaking hundreds of thousands of military and diplomatic cables to WikiLeaks, along with the widely seen “Collateral Murder” video, as a U.S. Army private in Iraq.

Assange has supported Manning’s case for years and, in at least one discussion in the Twitter group, defends the idea that she should be called by her chosen name. Assange railed against “gender essentialism,” which he called “regressive,” and argued that Manning’s plight as an imprisoned whistleblower matters more than her gender.

At times, he seemed to put political goals above questions of gender identity. An artist building a statue of Manning for an art project that would tour across Europe, Assange wrote, should not be expected to make the statue appear female because “Manning does have a Y chromosome and male genitalia.” Assange added that if the statue were brought to conservative areas, “it makes sense to not draw attention to the sex issue.” Depicting Manning as a female “would have turned off audiences in most countries,” the account said.

Assange also made comments about Manning’s friend Isis Lovecruft, a cryptographer and Tor developer, as well as a WikiLeaks critic. After another user pointed out that Manning and Lovecruft appear to be friends, the Assange posted, “That’s not good. Apparently ISIS ihas XY chromosomes.” Other members of the group wondered what Lovecruft’s real name is. “Bruce Anders,” Assange joked, presumably because it’s a masculine-sounding name.

“Blatant transmisogyny aside, it’s bizarre that Julian is starting rumors that I have XY chromosomes,” Lovecruft told The Intercept. “I’ve never had any genetic tests, so even I have no idea what my chromosomes are. It’s pretty hilarious that, all in one thread, these idiots can’t seem to figure out what my name or pronouns are, and yet they simultaneously purport to have a copy of my nonexistent 23andMe report.”

Manning declined to comment on the leaked messages. When asked in a recent interview with The Guardian for her opinion of WikiLeaks, she noted that she had first tried to contact the Washington Post and New York Times before going to the group. “I ran out of time, and that was the decision I made. I can’t change that,” she said, adding that she has had no contact with Assange since 2010.

Correction: Feb. 14, 2018

An earlier version of this story incorrectly implied that the Guardian exclusively obtained emails indicating that Sweden tried to drop extradition charges against Assange beginning in 2013. In fact, emails were publicly released following a successful effort by Italian journalist Stefania Maurizi to bring them to light.

Original Article

Source: theintercept.com

Author: Micah Lee, Cora Currier

In little more than a year, WikiLeaks would be engulfed in a scandal over how it came to publish internal emails that damaged Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, and the extent to which it worked with Russian hackers or Donald Trump’s campaign to do so. But in the fall of 2015, Trump was polling at less than 30 percent among Republican voters, neck-and-neck with neurosurgeon Ben Carson, and Assange spoke freely about why WikiLeaks wanted Clinton and the Democrats to lose the election.

“We believe it would be much better for GOP to win,” he typed into a private Twitter direct message group to an assortment of WikiLeaks’ most loyal supporters on Twitter. “Dems+Media+liberals woudl then form a block to reign in their worst qualities,” he wrote. “With Hillary in charge, GOP will be pushing for her worst qualities., dems+media+neoliberals will be mute.” He paused for two minutes before adding, “She’s a bright, well connected, sadistic sociopath.”

Assange’s thinking appeared to be rooted not in ideological agreement with the right wing in the U.S., but in the tactical idea that a Republican president would face more resistance to an aggressive military posture than an interventionist President Hillary Clinton would.

A few more months into the primary season, after Super Tuesday, Assange decried the idea of Clinton in the “whitehouse with her bloodlutt and amitions of empire with hawkish liberal-interventionist appointees like [Anne-Marie] Slaughter and digital expansionists such as Google integrated into the power structure. Then the republicans and trump in opposition constantly saying she’s weak and not invading enough.”

WikiLeaks has not made a secret of its opposition to Clinton. Assange had raised the possibility of her resigning as secretary of state in 2010, after WikiLeaks released its cache of U.S. diplomatic cables, and had also harshly criticized Clinton’s support for military action in Libya and the Middle East.

Still, Twitter messages obtained by The Intercept provide an unfiltered window into WikiLeaks’ political goals before it dove into the white-hot center of the presidential election. The messages also reveal a running theme of sexism and misogyny, contain hints of anti-Semitism, and underline Assange’s well-documented obsession with his public image.

The chats are from a direct message group between WikiLeaks and about 10 of its online boosters, described as a “low security channel for some very long term and reliable supporters who are on twitter.” Perhaps because of the “low security” designation, the chats do not shed much light on the most sensitive questions surrounding WikiLeaks and the 2016 election. They don’t reveal anything new about WikiLeaks’ relationship with the Trump campaign, although they are consistent with the group’s public statements casting doubt on claims by former Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone that he had advanced knowledge of the group’s anti-Clinton leaks. The chats don’t illuminate any connections with the Russian government or tell us anything about the identity of the source who provided WikiLeaks with emails from the Democratic National Committee and Clinton campaign chair John Podesta.

The archive spans from May 2015 through November 2017 and includes over 11,000 messages, more than 10 percent of them written from the WikiLeaks account. With this article, The Intercept is publishing newsworthy excerpts from the leaked messages.

A former supporter of and volunteer for WikiLeaks, who goes by the name “Hazelpress” (The Intercept does not know the person’s real name), set up the direct message group in mid-2015 and later decided to leak its contents to the media after news broke that WikiLeaks had secretly corresponded with Donald Trump Jr. during the election, urging candidate Trump to reject the results as rigged if he lost and requesting that the president-elect use his connections to get Assange an Australian ambassadorship. “At this point, considering the power exercised by WikiLeaks, [disclosing] literally anything Assange says is in the public interest,” Hazelpress told The Intercept, including Assange’s political position during the 2016 election, since “WikiLeaks purports to be a neutral transparency organization.”

One of the authors of this article verified the authenticity of the Twitter group messages by logging in using Hazelpress’s credentials. Throughout this article, The Intercept assumes that the WikiLeaks account is controlled by Julian Assange himself, as is widely understood, and that he is the author of the messages, referring to himself in the third person majestic plural, as he often does. The Intercept has also preserved typographical errors in quoted material.

WikiLeaks did not respond to a request for comment, sent several days before publication.

Disclosure: One of the authors of this article, Micah Lee, along with The Intercept’s co-founding editors Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, is a member of Freedom of the Press Foundation’s board of directors. For years, Freedom of the Press Foundation processed payments on behalf of WikiLeaks to bypass the financial censorship that the organization was facing. The foundation ceased doing so in December, stating that a blockade by credit card companies and PayPal had ended, but that the group still “strongly opposes any prosecution of WikiLeaks or Assange for their publishing activities.”Assange called the move “politically induced financial censorship” and alleged it was propelled by personal animosity from Lee, with whom he has clashed on Twitter.

The 2016 Election

Beyond the statement that Clinton was a “sadistic sociopath” and the explanation for why “it would be much better for GOP to win,” Assange surfaced other opinions on Clinton in the Twitter group:

After Super Tuesday, when Trump was leading in the Republican primary and Bernie Sanders suffered big losses to Clinton in the Democratic primary, Assange posted, “Perhaps Hillary will have a stroke.”

Assange believed that Clinton’s “role in the war in Libya is what should bring her down, however, the GOP is too close to others who have benefited to exploit this, itseems. That Hillary helped to sew the foundation for ISIS against pentagon generals advice seems huge. But the GOP resolutely ignores it. Hillary has so muc hslime on her shirt it is now hard to make dirt stick.” (Any ability by the Republican Party to leverage Libya against Clinton would have weakened further after Trump, who supported the Libya intervention, became the nominee.)

Some of the messages on Clinton are threaded with crass sexual allusions. In a publicly released State Department email that WikiLeaks re-published, Hillary Clinton asked her Chief of Staff Cheryl Mills, “What does ‘fubar’ mean?” Mills replied, “Fubar is unprintable on civil email.” (It stands for “fucked up beyond all recognition.”) Assange found this amusing. “WikiLeaks took Hillary’s FUBAR virginity,” the WikiLeaks account posted. “LOL. A well-deserved taking,” a Twitter interlocutor replied.

In the final months of the 2016 election, Stone repeatedly claimed that he had insider knowledge about WikiLeaks’ upcoming release of hacked emails. In early August 2016, Stone told a Florida Republican Party group, “I actually have communicated with Assange, including tweeting that ‘it will soon the [sic] Podesta’s time in the barrel’ before WikiLeaks published its cache of Podesta emails.” In the private Twitter group, WikiLeaks dismissed Stone’s claims, just as it had publicly. “Stone is a bullshitter,” Assange posted. “Trying to a) imply that he knows anything b) that he contributed to our hard work.”

In the following months, Stone continued to publicly claim he had “backchannel communications” with Assange.

Perspective on Russia

In June 2015, Assange emphasized the weakness of Russia’s geopolitical position relative to the United States. He told the Twitter group that the Kremlin is paranoid about foreign-funded NGOs because they push “invading ‘western’ cultural practices like gays and the internet,” which in turn pushes Russia to become more authoritarian. Russia was “on the defensive and terrified as the the US produces its next generation weapons and enroaches inexorably.” He further stated that all of Russia’s foreign military bases were under threat, and that “the U.S. hacks the hell out of it, and attempts to foment an orange revolution in an explicitly stated policy of regime change.”

Meanwhile, Assange maintained, Russia had only “minor imperialistic goals in its near abroad.”

“Be the Troll You Want to See in the World”

A major focus of the private Twitter group was strategizing online attack campaigns, including creating false identities, something that Assange explicitly encouraged.

Assange philosophized on how to approach such activities in conversation with a WikiLeaks supporter who told the group that Scottish Member of Parliament Paul Monaghan had retweeted her. The supporter added that others in the group should tweet at Monaghan as well to try for more retweets. Assange responded, “Exactly what we were hoping for. Be the troll you want to see in the world.”

Discussing another British politician, Assange suggested that the supporter change her account avatar to a “pretty blonde,” or a “dead actress if you want plausible deniability,” or to just create a new sock puppet account for trolling.

In another instance, Assange asked the group to “please troll this BBC idiot,” referring to journalist Chris Cook, who had been tweeting caustic messages about Assange that day. “Our interest is in having inflamitory tweets from him about JA/WL that we can use in legal cases to show that a toxic climate exists the UK (in the UK),” the next messages read.

“I don’t really remember his people causing me any issues,” Cook told The Intercept when asked about the messages.

“But He’s Jewish”

The direct messages from Assange also include an attack with anti-Semitic undertones against an Associated Press journalist.

In August 2016, AP reporter Raphael Satter tweeted a story he helped write about the harm caused when WikiLeaks publishes private information about individuals. “He’s always ben a rat,” Assange posted in the Twitter group in response. “But he’s jewish and engaged with the ((()))) issue.”

The parentheses refer to a neo-Nazi meme called “echoes,” which identifies Jews online by surrounding their names with three parentheses. In response to the meme, many Jewish people and some allies began to bracket their names on Twitter in a show of solidarity.

Satter continued to post negative tweets about WikiLeaks after promoting his story. “Bog him down. Get him to show statements of his bias,” Assange wrote, encouraging his supporters to start trolling. (Satter declined to comment for this article.)

WikiLeaks has faced charges of anti-Semitism before. In 2013, former WikiLeaks volunteer James Ball explained that he left the group over what he said was Assange’s close relationship with the Holocaust denier Israel Shamir; among other things, Ball alleged that Assange gave Shamir early access to the cache of U.S. State Department cables. Former WikiLeaks spokesperson Daniel Domscheit-Berg raised similar concerns about Shamir. Assange has downplayed WikiLeaks’ relationship with Shamir and denied giving him cable access.

In July 2016, a month before calling Satter a rat in the private Twitter group, WikiLeaks was criticized for posting a tweet suggesting that its critics were Jewish, again making use of the “echoes.”

An account in the London Review of Books by the would-be ghostwriter of Assange’s autobiography, Andrew O’Hagan, said that, amid preparations for the book in 2011, Assange had “uttered, late at night … many sexist or anti-Semitic remarks,” of which O’Hagan retained transcripts.

“The Accusation Industry Is Highly Profitable”

For years, Sweden had tried to extradite Assange from the United Kingdom in order to question him about allegations of rape and molestation. As of May 2017, Sweden is no longer seeking his extradition, and, according to emails exchanged with U.K. prosecutors, tried to drop extradition proceedings against him beginning in 2013, but were discouraged from doing so by prosecutors in the United Kingdom — where, nine months after Sweden’s extradition request was formally dropped, Assange still has an active arrest warrant.

Assange and his lawyers framed the sexual assault allegations as politically motivated, believing that if he were extradited, Sweden would send him to the United States, where he would face espionage charges related to his WikiLeaks work. This U.S. threat is the reason Ecuador has granted him asylum.

The Twitter group was intently focused on Assange’s sexual assault case, discussing how to discredit lawyers representing Assange’s accusers and journalists who covered the case in a manner unfavorable to Assange.

For instance, the group went after Elisabeth Fritz, a lawyer representing one of the women who has accused Assange of sexual assault. “Check out the sort of creature Fritz is,” Assange posted, linking to her firm’s website, which featured this photo.

Assange theorized that Swedish policies encouraged lawyers to take on rape cases for easy money and “public relations.”

“So the accusation industry is highly profitable,” he concluded. “Almost nothing to do other than bill the state for advertising your own law firm.”

Assange went on to accuse Fritz of working closely with Marianne Ny, Sweden’s chief prosecutor, to “tag-team the accused.”

Several hours later, the group was still angry about the courtroom photograph on Fritz’s website. “Money, influence, glamour for women helping women imprison men,” Assange wrote. “It may not be your type of feminism, but they don’t cae.”

Fritz told The Intercept that “WikiLeaks and Assange have, and continue to, deliberately spread false information in an attempt to turn public opinion against the women accusing Assange of sexual offenses, cast doubt on the accusations, and to discredit myself and the Swedish legal system.” She went on to say, “The leaked messages clearly show the level of contempt for women and disregard for the rule of law that WikiLeaks have.” (Ny declined to comment.)

Other women who crossed WikiLeaks came in for similarly gendered treatment: British blogger Laurie Penny was dismissed by Assange as a “fake leftist, and a manipulative, predatory exhibitionist” and called a member of the “cliterati.” The group also spent weeks in 2015 trying to preempt a Guardian article from Jessica Valenti about one of Assange’s accusers.

Asked to comment, Penny said in an email, “We don’t require Wikileaks to be the arbiter of what our feminist politics should be. I really cannot overemphasize how little I care what Julian Assange thinks about anything I do.”

Valenti wrote, “These messages speak for themselves: This is a powerful organization strategizing to discredit me and a brave woman who simply wanted to share her story.”

“Revenge Porn Against Jake”

The Twitter group also engaged in heated discussions of Laura Poitras’s documentary about WikiLeaks called “Risk.” Poitras had screened an early version of her film in the spring of 2016. In the Twitter group, Assange instructed supporters to add “nasty/damaging review quotes” to a collaborative document to argue for “edits of misleading material” before the film was released to the general public. “Risk” turned a critical eye on Assange’s attitudes toward his alleged sexual assault victims in Sweden. Assange, meanwhile, asserted that Poitras had broken various agreements she had made in order to gain access to WikiLeaks, a claim that Poitras has denied.

“Risk” also featured Jacob Appelbaum, a WikiLeaks volunteer and former employee of the nonprofit that publishes the Tor anonymity software. Beginning in June 2016, members of the Tor community came forward with accusations of rape and sexual assault against Appelbaum. The Tor Project confirmed that the sexual misconduct allegations were credible, and Appelbaum resigned, though he has denied all of the allegations and no criminal charges have been filed.

Poitras re-edited her film to address the charges and include references to WikiLeaks’ role in the 2016 election. The final version of “Risk” was released in May 2017. In it, Poitras discloses that she and Appelbaum had “been involved briefly in 2014” and that after they ended their relationship, “he was abusive to someone close to me.”

Amid the controversy, Assange accused Poitras of seeking profit and going after an ex. As the early media coverage of the final release of “Risk” started to appear, Assange wrote that it “seems to have transformed into some kind of revenge porn against jake.”

In the Twitter group, Assange never seems to entertain the idea that Poitras actually believed the women who accused Appelbaum; instead he stated that she was motivated by money and Oscar ambitions. “Profit matrix changed due to DNC and jakegate,” Assange wrote. “She’d have been exposed as sleeping with her subjects and making them appear positive after jakegate, so she had to attack them instead of defend against accusations of crossing the line.”

“Misogyny, self-pity, and calculated lies from Assange? That’s no surprise after our dealings with him and his lawyers on ‘Risk,'” Brenda Coughlin, producer of “Risk,” told The Intercept. “They repeatedly sought to censor the film to get us to remove Assange’s own sexist comments.”

In another exchange, Assange casts doubt on the charges against Appelbaum in the course of slamming the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Executive Director Cindy Cohn as a “stupid bay area neo-liberal” and “part of the anti-Jacob persecutrixity.” (Cohn declined to comment.)

Chelsea Manning and Gender

Some discussions in the Twitter group revolve around Chelsea Manning, formerly known as Bradley Manning, once WikiLeaks’ most significant source. Manning served seven years of a 35-year sentence for leaking hundreds of thousands of military and diplomatic cables to WikiLeaks, along with the widely seen “Collateral Murder” video, as a U.S. Army private in Iraq.

Assange has supported Manning’s case for years and, in at least one discussion in the Twitter group, defends the idea that she should be called by her chosen name. Assange railed against “gender essentialism,” which he called “regressive,” and argued that Manning’s plight as an imprisoned whistleblower matters more than her gender.

At times, he seemed to put political goals above questions of gender identity. An artist building a statue of Manning for an art project that would tour across Europe, Assange wrote, should not be expected to make the statue appear female because “Manning does have a Y chromosome and male genitalia.” Assange added that if the statue were brought to conservative areas, “it makes sense to not draw attention to the sex issue.” Depicting Manning as a female “would have turned off audiences in most countries,” the account said.

Assange also made comments about Manning’s friend Isis Lovecruft, a cryptographer and Tor developer, as well as a WikiLeaks critic. After another user pointed out that Manning and Lovecruft appear to be friends, the Assange posted, “That’s not good. Apparently ISIS ihas XY chromosomes.” Other members of the group wondered what Lovecruft’s real name is. “Bruce Anders,” Assange joked, presumably because it’s a masculine-sounding name.

“Blatant transmisogyny aside, it’s bizarre that Julian is starting rumors that I have XY chromosomes,” Lovecruft told The Intercept. “I’ve never had any genetic tests, so even I have no idea what my chromosomes are. It’s pretty hilarious that, all in one thread, these idiots can’t seem to figure out what my name or pronouns are, and yet they simultaneously purport to have a copy of my nonexistent 23andMe report.”

Manning declined to comment on the leaked messages. When asked in a recent interview with The Guardian for her opinion of WikiLeaks, she noted that she had first tried to contact the Washington Post and New York Times before going to the group. “I ran out of time, and that was the decision I made. I can’t change that,” she said, adding that she has had no contact with Assange since 2010.

Correction: Feb. 14, 2018

An earlier version of this story incorrectly implied that the Guardian exclusively obtained emails indicating that Sweden tried to drop extradition charges against Assange beginning in 2013. In fact, emails were publicly released following a successful effort by Italian journalist Stefania Maurizi to bring them to light.

Original Article

Source: theintercept.com

Author: Micah Lee, Cora Currier

No comments:

Post a Comment